East, in Eden: William Niblo and his Pleasure Garden of Yore

By Benjamin P. Feldman

It’s hard work being poor, impoverished in our ignorance of those who came before us. We walk New York’s streets, eat in its cafes, but turn a blind eye and a deaf ear to the giants who once walked the earth. Every so often though, the past rises up, through the cracks in the Belgian-block paving stones Crosby Street is quiet now, right by Housing Works Bookstore and Café. Once it resounded with bravos and huzzahs…

Standing at the cash register, I suddenly realized. I was in a place precious to me. I’ve been working on a biography of William Niblo, the once-famous tavern-keep and then creator of Manhattan’s best-known entertainment venue from its inception in 1828 until it closed almost seven decades later.

On my way downtown, I’d considered the fact that Niblo’s Garden once occupied almost the entire block between Broadway and Crosby, from Houston to Prince. But 126 Crosby had no meaning for me, and I got mixed up in my street plan, too. Sure enough though, I’d struck pay dirt. Housing Works’ Crosby Street stores sit on what to me is hallowed ground.

An Irish emigrant to New York in the earliest years of the 19th century, Niblo found work in David King’s tavern on Wall Street at Sloat Lane. In 1813 Niblo struck out on his own, taking possession of the former mansion of Tory sympathizer Frederick Phillipse at Pine and William Streets.

Just as Starbucks functions today as office space for so many people, coffee houses back in the day were centers of commerce, taverns and hostelries all rolled into one. Private rooms were available for business and social gatherings. The Bank Coffee House prospered and was the scene of many banquets of gargantuan proportions. Humongous green turtles were stewed and served. From the New York Evening Post, August 1, 1825:

WILLIAM NIBLO has just received 70 prime Green Turtles; they are kept healthy and fresh in the crawl at the foot of Warren Street. Parties and Clubs accommodated with Turtle and Game dinners in the very first style. Soup of a delicious flavor available at 11 O’clock every day. Mutton broth and gravy soups available at the same hour.

Niblo’s larder was well-stocked with local game. The bill of fare for February 15, 1822 included in the first course terrapin and ox-tail soups, as well as a hare soup made in the “Scotch” style and trout caught in season on Carman’s Pond in Long Island (which included Queens and Brooklyn as we know them today), hopefully kept on ice since having been harvested. A second course offered “a Bald Eagle, shot on the Grouse plains of Long Island: a very fine bird and very heavy, a remarkably fine Hawk and Owl, shot in Turtle Grove, Hoboken [where the Hoboken Turtle Club also announced the landing from clipper ships of oversized green terrapins for consumption of its members], an extraordinary fine Opossum taken in Plank Ridge, Virginia,” and some “remarkably fine Bear meat. The Bear was killed at the Big Bone (Lick) in Kentucky.”

One can hardly imagine the state of this flesh, in the days of no refrigeration, brought by horse and wagon over rutted roads and then ferry the 600+ miles from even the eastern-most parts of Kentucky to New York’s shores. But we’re not DONE, yet, even with the second course. Add, please: “A Raccoon, killed in Communipau [sic], very heavy. He is to be flayed and can be seen now hanging in the larder.” A giant swan, taken at Havre de Grace, Maryland rounded out the second course, while the third course offered game of all varieties, even reindeer tongues from Russia, pairs of canvas back ducks weighing in at 16 lbs. per pair, and Calipash and Calipee terrapins from the James River. The dessert course and beverages offered to wash down multitudes of pastries and tarts would put Sherry-Lehmann to shame.

Niblo prospered as a tavern keep and hotelier; his brother John operated Niblo’s Hotel at 112 Broadway, and William opened a second Bank Coffee House on the corner of Asylum (now West 4th) and Perry Streets in 1825 in the torrent of commercial development of Greenwich Village that ensued after the yellow fever epidemic of 1822 drove many lower Manhattan residents uptown to seek more permanent residences in what was then deemed a vastly more salubrious environment.

A second hotel in Harlem, serviced by a stage coach operated from the second Bank Coffee House, a pleasure garden by the East River, and manifold other catering activities supplemented Niblo’s income from his original Bank Coffee House, which he sold in 1828. Meanwhile, the resourceful fellow seized upon opportunities to provision public events, including renting a house for selling refreshments hard by the Union Course (near 75th Street in present-day Woodhaven, Queens) where on May 27, 1823, a crowd of 50,000 (including the then-governor of Florida, Andrew Jackson) assembled to witness a race won by American Eclipse (representing the Northern states of the USA) against Sir Henry (for the South). Niblo hired messengers to relay news of the event to his downtown Bank Coffee House, where results could be posted for all to see.

Around the time Niblo sold his first Bank Coffee House, he acquired control of a large site partially occupied today by Housing Works, where he operated an outdoor pleasure garden, previously known as Columbian Gardens. Elaborate fireworks displays drew enormous crowds to the entire block bounded by Broadway, Crosby Street, and Houston and Prince Streets, and a genteel saloon drew bourgeois folks from downtown. On July 4th, 1828 a theater opened in a pre-existing structure on the site, named Sans Souci, on what was otherwise mostly vacant ground, Before the Columbian Gardens opened in 1823, the site had been occupied by an equestrian facility with stables on Crosby Street, a girls’ riding academy, and a sometime circus grounds after its subdivision from the Bayard family farm.

Benjamin Johns Harrison, Annual Fair of American Institute at Niblo's Garden, c. 1845 (Image: Museum of the City of New York)

Niblo improved the property, hiring an army of carpenters to transform the old circus amphitheater into an enclosed “all-weather” proscenium stage theater. Ample outdoor space with lanterns, benches and plantings, together with saloon refreshment service and prices that catered to upper-middle class New Yorkers made Niblo’s Garden a pleasant alternative as a pleasure garden to the rougher entertainment precincts of the Bowery and other spots. Unaccompanied women were shunned at the gates.

Niblo prospered, both as a theater impresario as well as a landlord, lending his space out to all manner of entertainments, albeit tasteful for their times. Sacred music and orchestral productions occupied the same bills, and in the early 1840s, the premises were rented out for several weeks at a time for the “American Institute Fair,” an exhibition of science, technology and culture that presaged the Crystal Palace built on the northern side of the site of the present-day Bryant Park in the early 1850s. Trumpet competitions, acrobatic acts, and popular dramas also filled the stage. Further improvements were added, but all was for naught when Niblo’s Garden burned to the ground in 1846.

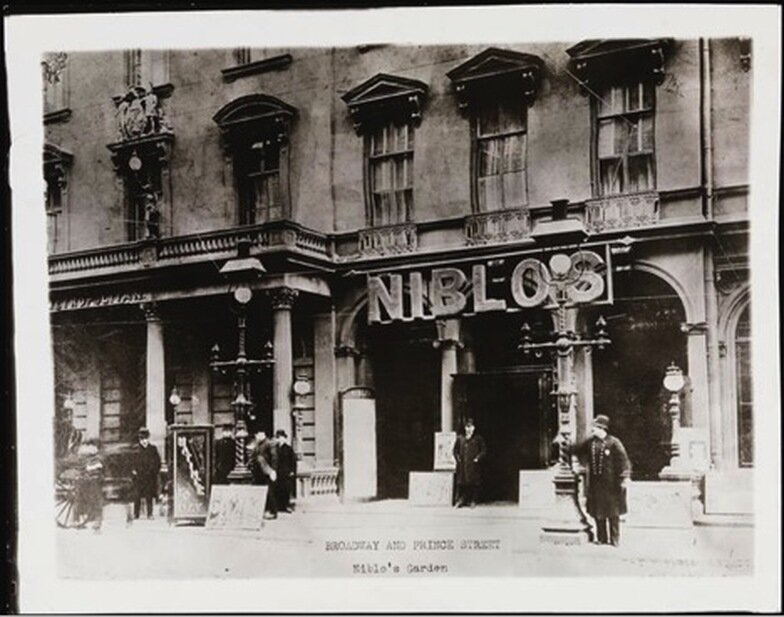

Courtesy of the New York Public Library

Though it was many months until Niblo’s re-opened, re-open it did in 1849, bigger and better than ever, and upon the construction, a few years later, of the Metropolitan Hotel on the easterly Broadway block-front where Niblo’s main entrance stood, the enterprise was physically incorporated in the luxurious new hotel lock, stock and barrel. Anyone who endeavored to be or stay a star of the New York and international stages, be they singer, thespian or ballet-artist, aeronaut or acrobat: all performed at Niblo’s to establish and maintain their reputations.

Niblo’s career as a theater impresario extended beyond his Garden, though. The infamous Astor Place Opera House riot occurred on May 10, 1849. With Niblo managing the facility, warnings of violence were cast aside with dire effects. Scores of innocent bystanders were killed and wounded in a fusillade from the New York State Militia called in to quell violence between supporters of English actor William Macready and the American Shakespearean Edwin Forrest.

Niblo was an observant Episcopalian, first a member of St. Thomas’ parish uptown and then a prominent member (and ultimately a warden) of Calvary Episcopal church that still stands on Park Avenue South and 21st Street.

There a stained glass window was installed with funds provided by Niblo in honor of his friend, the Reverend Francis Lister Hawks, who served as spiritual leader of Calvary from 1850-1862.

Tragedy struck once again when Niblo’s beloved wife Martha died in 1851, childless. Hers was the first interment in the Niblo family mausoleum at Green-Wood Cemetery, where her parents, Niblo’s niece Mary, and Niblo himself were eventually laid to rest. Niblo is said to have visited his wife’s grave every day that he was present in New York City, and he frequently brought friends there to enjoy the pond along the edge of which the tomb sits, stocked with goldfish.

Inside the Niblo mausoleum sits a recumbent figure of a sleeping little boy, placed there in 1855, one year after his wife’s interment. The sculpture perhaps represents an attempt at penance by the devoutly religious Mr. Niblo, for his having fathered an illegitimate son in 1816, prior to his marriage, and having abandoned the infant’s indigent mother. The unfortunate woman, Sarah Jane Hannan, placed the little boy in the Almshouse in 1818, and Niblo posted a $300 bastardy bond to pay for the hiring of outside wet nurses. It is not known if the boy, William Henry Niblo, survived beyond the age of six, though his name does appear in the 1822 Almshouse census. It is unlikely that the poor youngster did: most children were sent out to labor at or about seven years of age, in noxious factories. The mortality rates of Almshouse children were staggering, both in and out of the institution.

By May of 1861, William Niblo had tired of the hurly-burly of New York’s entertainment industry. Niblo crowned his career at Niblo’s Garden with the presentation of the Japanese Ball of June 25th, 1860, where 12,000 souls gathered to welcome the Imperial Japanese Delegation to New York on its first visit to western shores. He then turned his energies to travel and charitable work.

William Niblo lived in retirement for almost 20 years, but his name continued to adorn his theater in the Metropolitan Hotel until its demolition in 1894, after which Henry Havemeyer erected the huge loft building on the Broadway frontage that stands to this day.

It was at Niblo’s that the first American “musical” was staged in 1867. The Black Crook had a very long run and was revived several times there as well as being produced all over the country by many famous producers. Even after “legitimate” proscenium theaters moved uptown en masse to Union, then Herald, then Times Squares, Niblo’s Garden remained. The huge auditorium and adjacent rooms and dining facilities were rented out for entertainments, benefits, and religious society functions. Shown below is the theater’s entrance proudly stands, a few years before its storied Broadway run ended.

William Niblo passed away in August, 1878, at the age of 88, honored and revered by generations of theater goers and gourmands of yore. I and other visitors to Housing Works Café and Bookstore tread the same ground that Niblo’s patrons enjoyed so well, feeding their minds and eyes alike, a tradition unbroken in lower New York.

Benjamin Feldman has lived and worked in New York City for the past forty-three years. His essays and book reviews about New York City and American history and about Yiddish culture have appeared in the Blotter, The New Partisan Review, Columbia County History and Heritage, Ducts literary magazine, and on his blog, The New York Wanderer. Feldman is the author of Butchery on Bond Street: Sexual Politics and the Burdell-Cunningham Case in Ante-bellum New York, and Call Me Daddy: Babes and Bathos in Edward West Browning’s Jazz-Age New York. A biography of Niblo is in the works.