Feeding Gotham: The Political Economy and Geography of Food in New York, 1790–1860

By Gergely Baics

The following is an excerpt from the author's new book,

Feeding Gotham:

The Political Economy and Geography of Food in New York, 1790–1860

Princeton University Press, 2016

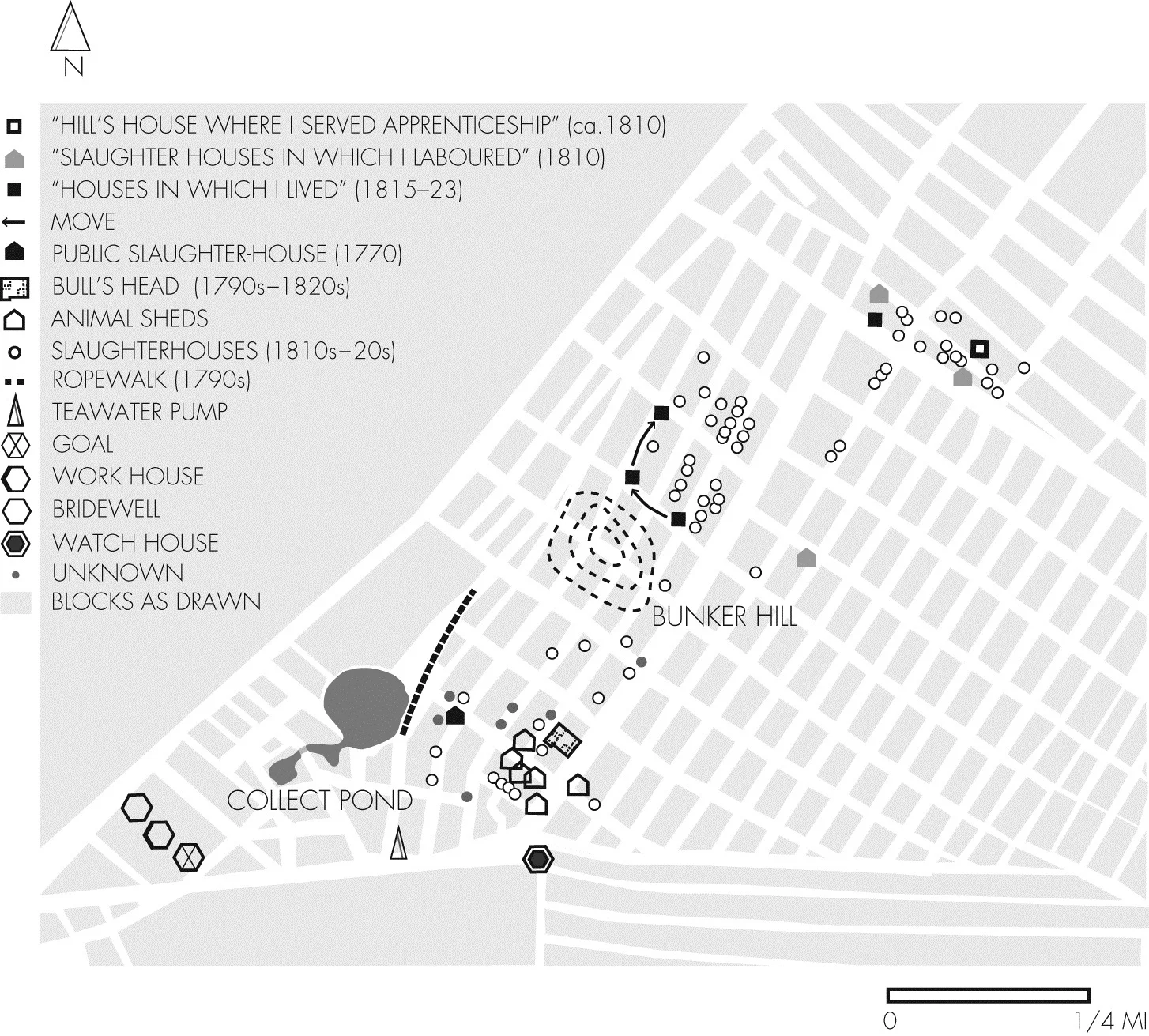

There can hardly be better testimony to this sentiment of neighborly bonds than an intriguing map drawn by a mysterious butcher from memory looking back at his youth in the 1810s and 1820s from the distance of three decades later. Following up on each clue still leaves his identity uncertain. Nonetheless, a good guess is Ernest Keyser, who is first mentioned as a butcher living at 140 Bowery in the 1812 city directory, which is confirmed by the council’s approval of his stall at Bear (Hudson) Market that year, and who is last mentioned as an active butcher at Washington Market still residing in the area according to the 1841 directory.[69] Whether Keyser or not, the butcher in his old age, around 1850, copied down from two published maps the streets of the meatpacking district, and then meticulously labeled on his sketch public buildings and natural landmarks, places of professional import, his neighbors and their slaughterhouses, and, most captivating, his personal narrative.[70] The process involved a small sketch first, which was later consolidated into a larger final version. The present redrawing of this mental map (figure 2.6) makes every effort to preserve the integrity of the author’s perspective, which bespeaks volumes of a young butcher’s personal experience of living and working in the neighborhood.[71]

Figure 2.6. Mental map of unknown butcher, ca. 1805–23.(Sources: See text and appendix A)

Immediately evident from the map is how the butcher’s retrospective blurs time, conflating landmarks from two different periods. The neighborhood is dotted by a little over sixty slaughterhouses, most of them located in two clusters a few blocks west of the Bowery below Houston Street, and a third one right northeast from where the two thoroughfares intersected. On the butcher’s original map, they are marked with a reddish color, and more than half of them are labeled with the butchers’ names, dating the map’s central theme around the 1810s and early 1820s. A few uncolored footprints might mark some butchers’ homes, while a feather-like pattern indicates animal sheds, especially near the Bull’s Head. The Bull’s Head, still in operation at the time, is not the only prominent site. Other landmarks—the Bridewell, Work House, Gaol, Bridge, Tea Water Pump, and Watch House—are also recovered either from memory or from the 1797 Taylor-Roberts map. More relevant, the Public Slaughter-House, marked with the date 1770, is diligently reconstructed, surrounded by the private killing sheds of a later generation of butchers. Other ghosts from the past include Bunker’s Hill, which featured the city’s bull-baiting arena after the Revolution, the Rope Walk, and the Fresh Water Pond, which had largely been drained by the author’s youth. As the old butcher reconstructed his neighborhood, two separate geographies of slaughtering were assembled on the same map: one clustered around a centralized facility nearby the Collect Pond, and another one defined by the private killing sheds of neighborly butchers.

This was a place the butcher intensely remembered. His symbols evoke the familiar streets and dense social networks that tied together people’s lives personally and professionally. More often than not, he summons the butchers by names. In other cases, the map recalls his regular walks, as if passing by the fellow butchers’ slaughterhouses. Onto this landscape, he inserts his personal narrative with remarks such as “slaughter houses in which I laboured” or “houses in which I lived.” Most intriguing, one note identifies “Hill’s house where I served apprenticeship,” also indicating the corresponding slaughtering pen across the street. The same setting of house with adjacent killing shed defined his working conditions for Hartell. By the early 1810s, but definitely no later than 1815, he must have established his own business, for he no longer identifies his home under another butcher’s name. Instead, he labels three separate houses between 1815 and 1823, all located in close proximity to one another between Spring and Broome Streets, two or three blocks west of the Bowery. Presumably, his slaughterhouse must have been nearby, which confined his moves to the immediate vicinity. If he was indeed Ernest Keyser, his killing shed stood exactly equidistant from the three houses.

The map’s narrative illustrates how the butcher’s social and professional worlds were caught up within the narrow boundaries of the neighborhood. They defined where he lived and worked, with whom he associated, how he advanced in his trade, and how he made sense of his life from a few decades distance when trying to reassemble the pieces. Why he felt the need to draw the map, how he came to choose such an unusual medium, and to whom it was intended, one can only guess. The fact that except for some clues the map leaves the author’s identity obscure suggests that his audience was himself: an exercise of memory rather than remembrance. In its unusual quality, the mental map testifies to the genuine experience of a closely knit community of craftsmen. This community oriented the butcher’s trade: from the home, to the slaughterhouse where he labored, and the public market where he served customers. The map also indicates that the public market system was not simply a government service, at least not in the sense that the Croton system was to become a quarter century later; rather, it was an institutional framework embedded within public and private interests and responsibilities, with the butchers as one group of invested stakeholders.

Gergely Baics is an Assistant Professor of History and Urban Studies at Barnard College, Columbia University.

[69] One clue indicates that the butcher drawing the map, in fact, may have been Ernest Keyser. Specifically, among the butchers listed on the sketch and the final map, only in his case did the author write “Ernest Keyser born” and “Ernest Keyser born Old House,” which building he also marked up carefully. Further, Ernest Keyser’s home addresses as listed in the city directories match up reasonably well with the butcher’s houses between 1815 and 1823 as marked on the map. Unfortunately, the correspondence is not perfect, thus the identity cannot be confirmed with certainty. David Longworth, Longworth’s American Almanac, New York Register,and City Directory, for the Thirty-Seventh Year of American Independence (NewYork: David Longworth, 1812), 172; Thomas Longworth, Longworth’s American Almanac, New-York Register, and City Directory, for the Sixty-Sixth Year of American Independence (New York: Thomas Longworth, 1841), 408; John Doggett Jr., The New-York City Directory, for 1849–1850 (New York: John Doggett Jr., 1849), 239;New York (N.Y.). Common Council, Minutes of the Common Council of the City of New York, 1784–1831 (MCC) (New York: M. B. Brown Printing & Binding, 1917),6:611; 7:77, 7:134.

[70] The note “1797” on the map indicates that the butcher most probably worked from the Taylor-Roberts map of 1797. Another note, “1820 to 1840,” suggests that he used a second map for the missing streets, which also helps explain why the map contains features from two different periods.

[71] For sources and methods used to produce this map, see appendix A.