Opening Credits: Urban Redevelopment, Industrial Policy, and the Revitalization of Motion Picture and Television Production in New York City, 1973-1983

By Shannan Clark

In the decades that followed the Second World War, deindustrialization and disinvestment ravaged New York City, leading to its near bankruptcy in 1975. The loss of hundreds of thousands of jobs in the manufacturing, transportation, and distribution sectors badly hurt the metropolitan economy, but cultural deindustrialization also contributed to the city’s crisis. Four of the seven daily mass-circulation newspapers published in Manhattan at the beginning of the 1960s, for example, ceased operations over the course of the decade, resulting in thousands of layoffs. Mass-circulation magazines that were based in the city, most notably Life and Look, downsized in the late 1960s before closing in the early 1970s, leading to more lost jobs. The production of television programming for primetime broadcast, an activity which had started in New York, likewise declined over the postwar era. As network executives came to prefer filmed rather than live programming by the late 1950s, primetime television production migrated to the West Coast, thus following the course taken by the motion picture industry when it decamped for Hollywood in the early-twentieth century. [1]

New York State Governor Hugh Carey (center) along with supporters of the Astoria Motion Picture and Television Center Foundation in 1978.

With the city’s fortunes reaching their nadir in the mid-1970s, a disparate coalition of union activists, creative professionals, cultural advocates, public officials, media executives, and real estate developers began to coalesce to rebuild the motion picture and television production industry in New York. The participants in this process acted at a pivotal conjuncture, working at the dawn of an era of austerity, the duration of which they could not foresee, but with a consciousness that was still shaped by their formative experiences in an earlier era of abundance that was coming to an end. They experimented and improvised within a rapidly shifting economic and political environment during the late 1970s and early 1980s. Some of the key individuals and institutions involved in the revitalization of motion picture and television production in the city from the outset wished to channel public resources to sustain profit-oriented commercial activities. Others, however, hoped that public investment could pave the way for the operation of production facilities by a nonprofit, cooperative, or genuinely public entity, with some measure of democratic or community control. The evolving process by which the industry’s reinvigoration took place demonstrates the contingencies and complexities inherent in the city’s remaking during these years. [2] Certain types of economic activities — and certain categories of workers and citizens — came to be favored within the new white-collar metropolis, most obviously with the city’s growing dependence on financial services, but also with its renewed commitment to being a global hub in the production of culture and knowledge. The revitalization of the New York’s motion picture and television industry was one chapter in the story of who would have a right to the city in the late-twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, and who would be deprived of access to its spaces and opportunities.

Although Mayors John Lindsay and Abe Beame had launched economic development initiatives in response to the city’s accelerating decline during the late 1960s and early 1970s, their attempts only achieved middling results at best. The Lindsay administration’s program to promote the city’s media exemplified these shortcomings. It succeeded in attracting more feature motion pictures to use New York for location shooting in the short term, but this failed to lead to any related growth in studio filming or other phases of the production process. [3] For television, the situation unequivocally worsened. Within those segments of the industry that had largely remained in New York following the primetime exodus of the late 1950s — such as game shows, talk and variety shows, and daytime soap operas — a disturbing new trend of relocation to the West Coast emerged. By 1975, the Beame administration, in its desperation to avert bankruptcy, went as far as to propose levying a new 4% tax on advertising agency billings, which if implemented would have drastically curtailed the production of television commercials in the city. [4]

Filming on the backlot at Paramount Studios in Astoria in 1929.

During the mid-1970s, the unions in New York’s contracting motion picture and television industry took the lead in pressing to expand the volume of production in New York. In part, the shift was motivated by growing frustration with Beame’s administration for failing to sustain even his predecessor’s inadequate level of support for the industry. Although many executives contended that excessively high production costs, especially for below-the-line craft labor, were the primary obstacle to increasing production in New York, the unions argued that the main problem was one of inadequate facilities. [5] This framing was important for the unions, not only to maintain labor standards for those members who were still working in the industry, but also to bolster the unions’ claim that they had an important role as partners in the formulation and implementation of industrial policy. Yet even winning acceptance of the notion that a lack of space was in fact a major hinderance to expanding motion picture and television production and employment led immediately to other difficult quandaries. Where were the sites in the city suitable for redevelopment as studio facilities? What public or private entities would furnish the funds for redevelopment projects? Who would be the prime beneficiaries of these projects? Significantly, providing space for new stages and related production services that would boost media employment did not automatically take precedence over other economic uses for other urban constituencies. A 1975 proposal to repurpose the Brooklyn Army Terminal in Sunset Park as a motion-picture studio, for instance, was blocked to accommodate a competing, though ultimately also shelved, scheme to construct a container transshipment facility on the site in an attempt to generate new employment opportunities for longshoremen. [6]

One site that attracted interest was the former Paramount Studios property in Astoria. Opened in 1919, the studio had been a bustling hive of activity in its early years. Even as the other major motion picture studios concentrated production in Hollywood during the 1920s, Paramount continued to shoot a sizeable share of its total output in Astoria. As the company struggled financially during the Great Depression, however, it followed the lead of its competitors, and over the course of the 1930s the volume of filming in Astoria gradually declined. Following the entry of the United States into the Second World War, the company sold the complex to the Army to produce training films. In 1970, the Army officially decommissioned the facility, which was in a considerable state of disrepair, and two years the city obtained access, but not title, to the site. [7] During the mid-1970s, the proponents of bringing motion pictures and television back to Astoria lined up a handful productions to make limited use of portions of the vacant complex as a way of demonstrating its potential viability, but the casts and crews of these endeavors had to endure the derelict state of the buildings and their barely functional electrical, plumbing, and heating systems. With the city seemingly able to do little more than hand over the keys, and the major firms in the industry unwilling as yet to invest in new production capacity in the east, the unionists took matters into their own hands. In the fall of 1976, they launched the Astoria Motion Picture and Television Center Foundation, with Sam Roberts and Larry Barr of the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE) and John McGuire of the Screen Actors Guild (SAG) as its key leaders. This new nonprofit assumed responsibility for coordinating access to the stages along with raising funds for critical improvements. It also defined its mission as including historic preservation and cultural programming, a savvy move that widened the range of possible funding sources available to support its work. [8]

Beginning in 1977, the volume of production at Astoria steadily began to increase, with the completion of The Wiz, directed by Sidney Lumet, representing an important milestone as the first feature motion picture shot entirely at the site since the 1930s. [9] Various sources of public and private funding allowed basic improvements to the complex that were crucial to operations. In order to minimize payroll, the foundation tapped into federal funding through the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA) to pay personnel, including for its cultural programming efforts. [10] While the city’s fiscal woes limited its ability to contribute from its own funds, it helped the foundation make use of federal money furnished through Community Development Block Grants. State money also flowed, beginning in 1978, through grants from the New York State Arts Council and the state Department of Commerce. [11] In 1979, the state proposed a major investment of almost $10 million dollars through its Urban Development Corporation to rebuild and expand the Astoria Center, with the facility remaining under nonprofit operation, or possibility being transferred to a public authority. [12] Skyrocketing interest rates and the resulting financial instability, however, scuttled this proposal and similar ones to secure funding for a complete rebuilding under nonprofit or public auspices.

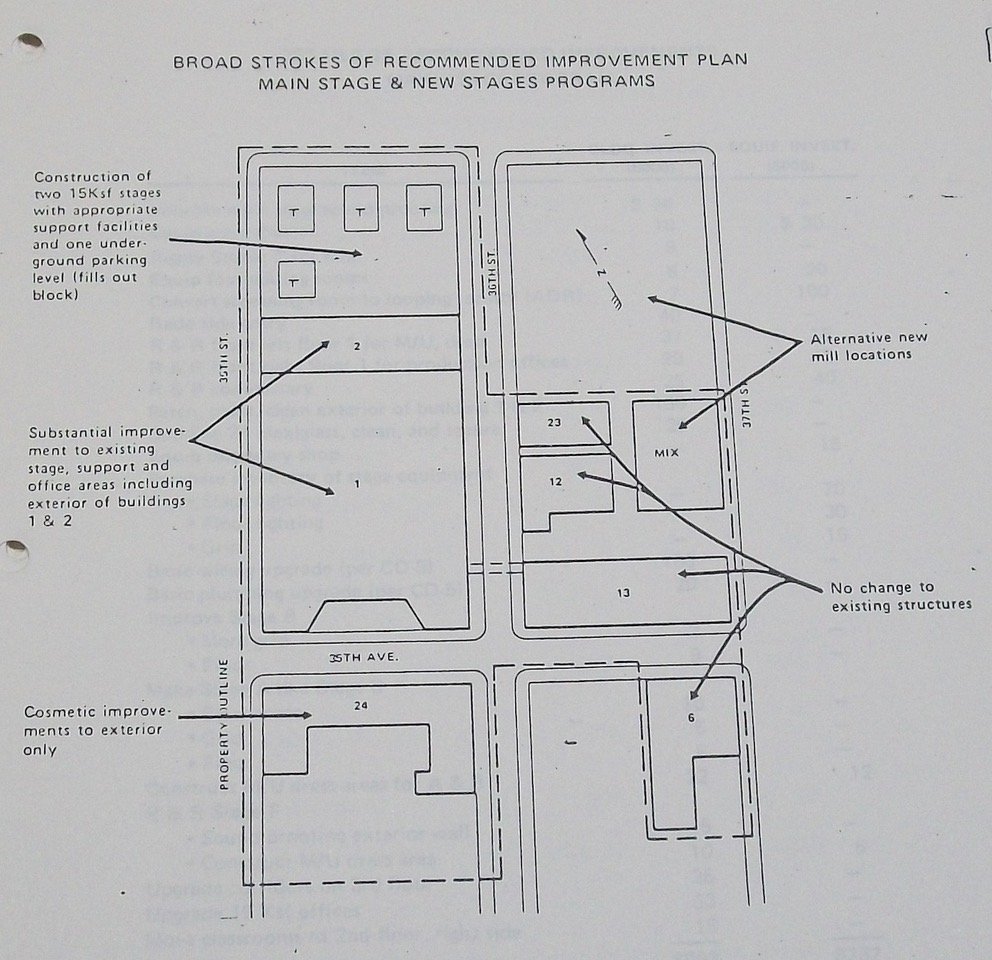

Diagram outlining the reconstruction of Astoria Studios proposed in 1979 by the New York State Urban Development Corporation.

Given the ongoing precarity that resulted from nonprofit status in this environment, with the unpredictable flow of short-term grants and appropriations interfering with the everyday functioning of the studio, many of the foundation’s board members were receptive to a proposal from real estate developer George Kaufman to transfer studio operations to a for-profit enterprise. Under the tentative terms of the agreement they approved in September 1980, the newly established Astoria Studios Development Corporation, headed by Kaufman, assumed responsibility for booking and maintaining the existing stages, and for coordinating construction of the new stages and the completion of other renovation projects. [13]

Mayor Ed Koch pledged the public sector’s support for motion picture and television production in the city, and hoped to claim some credit for its revitalization during his tenure, but most New Yorkers had little idea just how extensive the deployment of increasingly scarce public resources toward an endeavor for private profit actually was. Kaufman and his partners committed only $2,000,000 of their own money under the initial terms of the development package. City agencies, meanwhile, coordinated applications for a $2,500,000 federal grant from the Economic Development Administration, another $2,000,000 of federal funds through an Urban Development Action Grant, and $4,000,000 of federal loan guarantees. In addition, the city directly contributed $1,750,000 and conferred a 22-year tax abatement for the property. In exchange, the city received a 35% share of the operating corporation’s net profits after debt service. [14] At a time when New Yorkers had endured years of cuts in public services due to the city’s fiscal crisis, municipal employees had suffered years of retrenchment, and the manufacturing and distribution sectors continued their precipitous decline, it seemed that there was no austerity for the proponents of increased motion picture and television production.

This formula for financing the reconstruction of Astoria Studios quickly established a pattern for using public funds to subsidize the production infrastructure necessary for the motion picture and television industry in New York to expand. The following year, a new development package was announced for the development of another studio in Queens, this one a few blocks to the south in Long Island City at the site of the former Silvercup Bakery. For this project, funds from a pair of Urban Development Action Grants, other monies from city and state sources, plus tax abatements permitted the conversion of this discarded plant into sound stages and ancillary production facilities. [15] While the Astoria complex had historically been a place for making movies, the success of Silvercup Studios demonstrated the feasibility of private redevelopment of former manufacturing and distribution sites for media production through public subsidy, opening a path for similar projects around the metropolitan areas over the last forty years.

Kaufman Astoria Studios, ca. 2010.

Furthermore, the specifically crafted packages of government assistance for Astoria and Silvercup in the early 1980s foreshadowed subsequent lobbying for the public sector not only to help New York’s motion picture and television industry with critical capital investments, but also to provide general subsidies for operations. This culminated in the eventual enactment in 2004 of a state refundable tax credit for the motion picture and television industry. By the mid-2010s, producers could claim a refund for up to 30% of all below-the-line costs, which amounted to a tax break that routinely totaled more than $600 million annually. [16] Yet if the type of industrial policy for the media that emerged in New York City during the 1970s and 1980s appears in retrospect as a textbook example of neoliberal urban governance, the actual path that led to the adoption of this approach was filled with uncertainly, contingency, and ambiguity.

Shannan Clark is an Associate Professor in the Department of History at Montclair State University. He is the author of The Making of the American Creative Class: New York’s Culture Workers and Twentieth-Century Consumer Capitalism (2021).

[1] On New York’s cultural deindustrialization, see Shannan Clark, The Making of the American Creative Class: New York’s Culture Workers and Twentieth-Century Consumer Capitalism (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2021), 339-71.

[2] My thinking about this process of experimentation within this period of economic recession and fiscal constraint has been influenced by Benjamin Holzman, The Long Crisis: New York City and the Path to Neoliberalism (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2021) and Claire Dunning, Nonprofit Neighborhoods: An Urban History of Inequality and the American State (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2022).

[3] For a sunny assessment of the Lindsay administration’s efforts to promote location filming for feature-length motion pictures in New York City, see Lizabeth Cohen and Brian Goldstein, “Governing at the Tipping Point: Shaping the City’s Role in Economic Development,” in Joseph P. Viteritti ed., Summer in the City: John Lindsay, New York, and the American Dream (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014), 162-92.

[4] Maurice Carroll, “$434-Million Rise in Taxes Planned by City in Crisis,” New York Times, May 13, 1975; Philip Dougherty, “Agency Tax Proposal Stirs Ire,” New York Times, May 27, 1975; and Steven Weisman, “Beame Uncertain on New Tax,” New York Times, June 15, 1975.

[5] On the views of executives, see Walter Wood (Director of the Mayor’s Office of Motion Pictures and Television), Confidential minutes of meeting with executives in charge of production planning – all major studios – Los Angeles, September 10, 1975, American Federation of Television and Radio Artists, New York Local Records, New York University Special Collections Division (hereafter AFTRA-NYC), Box 24, Folder 46; and Wood memo to Kenneth Groot (executive secretary New York AFTRA) , September 16, 1975, AFTRA-NYC, Box 24, Folder 46.

[6] Walter Wood memo to Kenneth Groot, September 24, 1975, AFTRA-NYC, Box 24, Folder 46; Arlene Moran, minutes of initial meeting planning meeting for consideration of usage of the Brooklyn Army Terminal site, AFTRA-NYC, Box 24, Folder 46.

[7] Jerry Oster, “Hollywood’s Old Address in Queens,” New York Daily News, June 8, 1975; Fraser, “Koch Predicts Astoria Studio’s Rebirth”; Richard Koszarski, “Rediscovering Astoria Studio,” Back Stage, June 5, 1981.

[8] Astoria Motion Picture Foundation, “The Dream Factory” promotional booklet, 1976, AFTRA-NYC, Box 24, Folder 27. The nonprofit’s official name was changed to the Astoria Motion Picture and Television Center Foundation very shortly after the booklet’s issue.

[9] Richard F. Shepard, “Film of ‘Wiz’ Will Be Made at Queens Site,” New York Times, April 9, 1977; Astoria Motion Picture and Television Center Foundation, Invitation to Mayoral press conference, April 11, 1977, AFTRA-NYC, Box 24, Folder 27.

[10] Astoria Motion Picture and Television Center Foundation, Fundraising solicitation, undated (but spring 1977 from context), AFTRA-NYC, Box 24, Folder 27; Astoria Motion Picture and Television Center Foundation, Minutes of Board of Directors meeting, May 23, 1977, AFTRA-NYC, Box 24, Folder 27.

[11] Lawrence Barr memo to Dear Board Member, May 18, 1978, AFTRA-NYC, Box 24, Folder 27; Lawrence Barr, “Progress Report #5,” August 14, 1978, AFTRA-NYC, Box 24, Folder 29; Astoria Motion Picture and Television Center Foundation, Secretary-Treasurer’s report to the Board of Directors, August 14, 1978, AFTRA-NYC, Box 24, Folder 27; Astoria Motion Picture and Television Center Foundation, Minutes of Board of Directors meeting, August 14, 1978, AFTRA-NYC, Box 24, Folder 28.

[12] New York State Office for Motion Picture and Television Development, Production Committee meeting minutes, March 14, 1979, AFTRA-NYC, Box 24, Folder 30; Astoria Motion Picture and Television Center Foundation, Minutes of Board of Directors meeting, March 29, 1979, AFTRA-NYC, Box 24, Folder 28; New York State Urban Development Corporation, “Excerpts from Feasibility Study: Improving and Expanding the Astoria Film Studios,” June 1979, AFTRA-NYC, Box 24, Folder 30; Astoria Motion Picture and Television Center Foundation, Minutes of Board of Directors meeting, July 5, 1979, AFTRA-NYC, Box 24, Folder 28.

[13] Astoria Motion Picture and Television Center Foundation, Minutes of Board of Directors meeting, August 14, 1980, AFTRA-NYC, Box 24, Folder 28; Statement by George Kaufman to the New York City Council for Motion Pictures, Radio, and Television, September 29, 1980, AFTRA-NYC, Box 24, Folder 47.

[14] C. Gerald Fraser, “Koch Predicts Astoria Studio’s Rebirth,” New York Times, September 6, 1980; “Astoria’s Expanded Stages Hopefully Ready by 1982,” Variety, September 10, 1980; “Infusion of $10,000,000 Pends as Astoria Aid,” Variety, September 3, 1980; “Various Govt. and Other Monies Assure Re-Structure at Astoria,” Variety, October 8, 1980; “Public, Private Elements Unite to Modernize the Astoria Studios,” Variety, February 24, 1982. For a brief summary of the Urban Development Action Grant (UDAG) program, see Rebecca Marchiel, After Redlining: The Urban Reinvestment Movement in the Era of Financial Deregulation (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2020), 152-54.

[15] Minutes of the New York City Council for Motion Pictures, Radio, and Television, September 29, 1980, AFTRA-NYC, Box 24, Folder 47; Minutes of the New York City Council for Motion Pictures, Radio, and Television, February 24, 1981, AFTRA-NYC, Box 24, Folder 47; Shawn Kennedy, “A Film and TV Base Is Growing in Long Island City,” NYT, November 23, 1983; “1st Silvercup Studio Claims Quick Sellout,” Variety, August 17, 1983; and Jim Robbins, “N.Y. Studio Facilities Prepare for ’84 after Up & Down Year,” Variety, Wednesday, January 11, 1984.

[16] See Neil de Mause, “New York Is Throwing Money at Film Shoots, but Who Benefits?” Village Voice, October 11, 2017, https://www.villagevoice.com/new-york-is-throwing-money-at-film-shoots-but-who-benefits/; Neil de Mause, “Lights, Camera, Extraction! Inside Hochul’s Plan to Shovel Hundreds of Millions More into TV and Film Shoots,” Hell Gate, February 22, 2023, https://hellgatenyc.com/film-tax-credits-more-guys-with-walkie-talkies; and Ken Girardin, “The Special Effects Behind NY’s Hollywood Giveaway,” Empire Center for Public Policy blog, February 24, 2023, https://www.empirecenter.org/publications/special-effects-behind-nys-hollywood-giveaway/.