Alice Austen: Amateur or Professional?

Miss Alice Austen and Staten Island’s Gilded Age

by Bonnie Yochelson

Amateur or

Professional?

Like millions of Americans and many of her friends, Alice traveled to Chicago in the summer of 1893 to see the World’s Columbian Exposition. As usual, she took her camera, but uncharacteristically, she copyrighted 25 of her photographs and made numerous prints, perhaps intending to sell them. In the next few years, Alice embarked on several projects with commercial potential but ultimately abandoned the idea of becoming a professional photographer. In an era when many exceptional women amateurs became professionals – including fellow New Yorkers Gertrude Kasebier and Jessie Tarbox Beals – Alice chose otherwise.

Self Starting for Chicago, July 1, 1893. Collection of Historic Richmond Town, 50.015.6032

Alice made this self-portrait before leaving home for Chicago. She put down her alligator-skin traveling bag, bid farewell to Punch, and hid the camera’s shutter release under her raincoat. That she memorialized her departure suggests that the trip to Chicago was more than a casual visit.

Peristyle and golden statue of Liberty (sic), July 10, 1893. Collection of Historic Richmond Town, 50.015.5276

Alice photographed the main sights of the Chicago exposition expertly, if impersonally. She owned (and kept) an official souvenir book of exposition photographs, which may have served as her model. This photograph of the Statue of the Republic, which stood at the center of the fairgrounds, met professional standards. Alice copyrighted it and made multiple prints.

Fire breaking out in tower of Cold Storage Building, July 10, 1893. Collection of Historic Richmond Town, 50.015.5281

One of Alice’s exposition photographs stands apart from the rest. When a fire broke out in the chimney of the Cold Storage Building, Alice was on a fairgrounds train, which afforded her a bird’s eye view of a tragedy in the making. Firefighters could not reach the 191-foot chimney, built to impress the crowds, and sixteen people died. Alice copyrighted and made multiple prints of this view but did not market it.

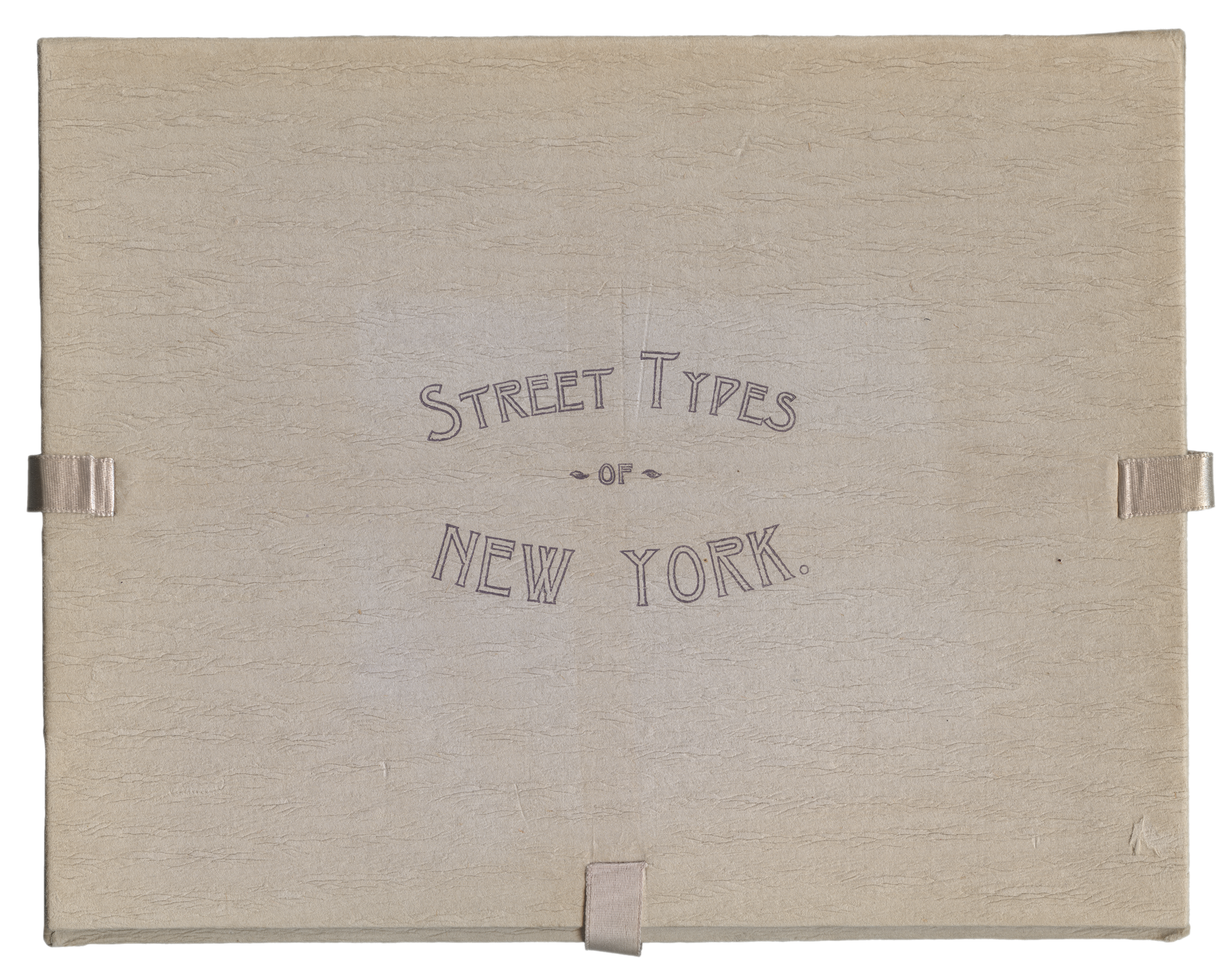

Street Types of New York

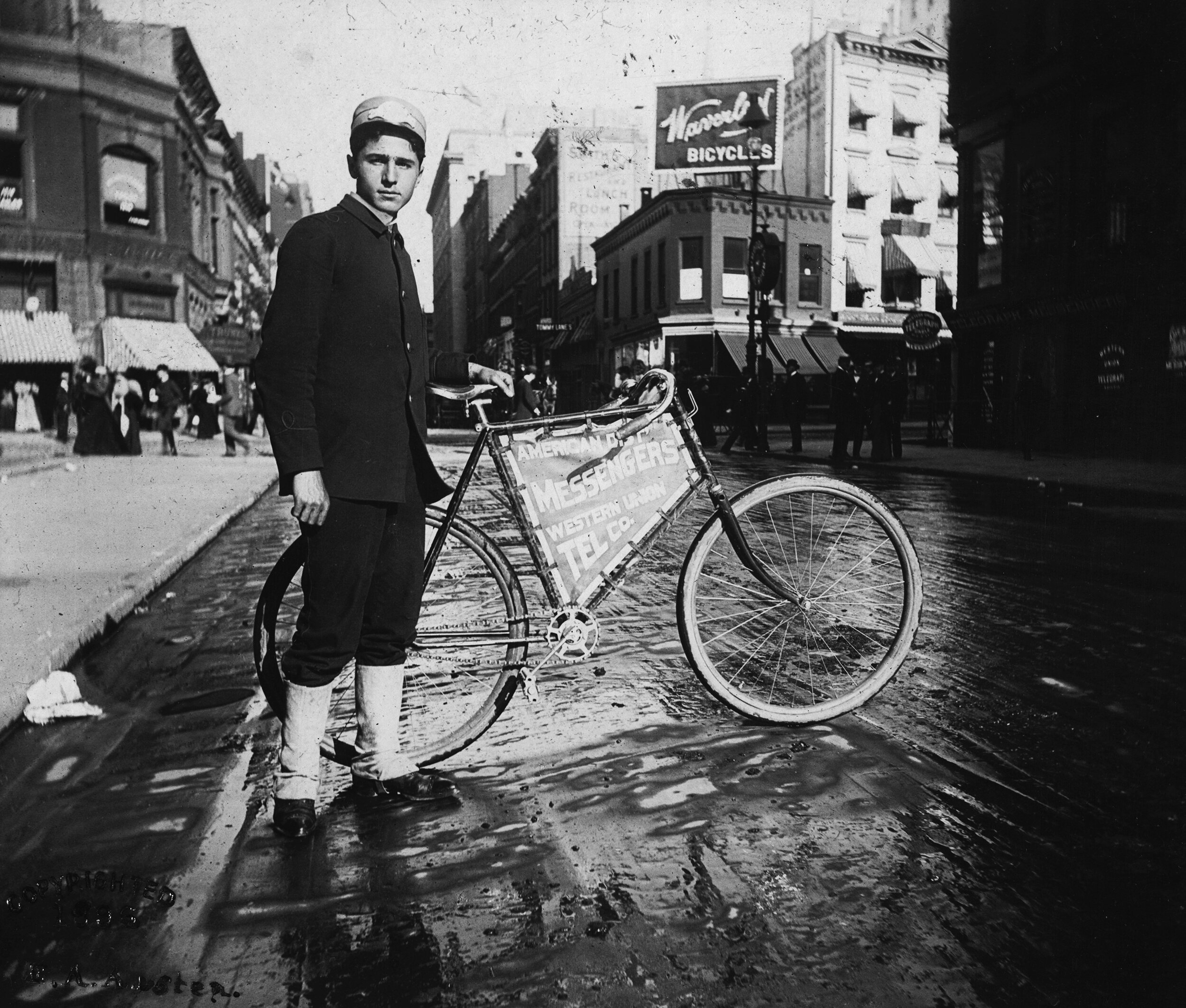

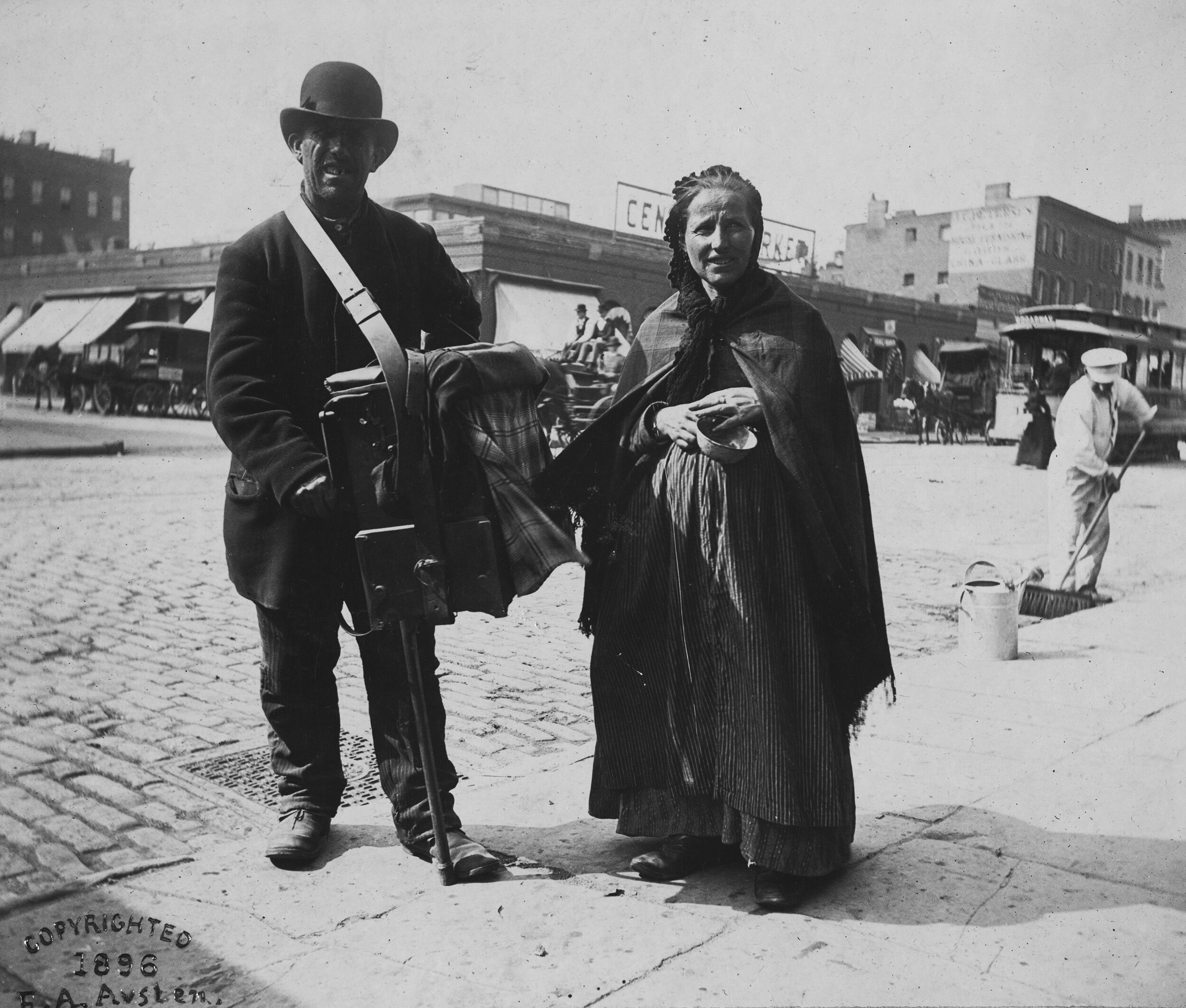

Alice was used to Manhattan’s crowded, noisy streets, which she regularly navigated to shop and attend performances. In 1895, she began to explore working class neighborhoods and soon embarked on a series of portraits of tradesmen from all over the city. In 1896, she exposed more than 70 negatives, made dozens of prints, and registered 18 images for copyright. She chose twelve for a portfolio and placed them between cardboard covers bearing the printed title, “Street Types of New York.” This project, for which Alice wandered the city streets, approached strangers and convinced them to pose for her, was uniquely ambitious and innovative. Producing the portfolio was the closest Alice came to publishing work under her name.

Egg stand group, April 18, 1895. Collection of Historic Richmond Town, 50.015.5933

Hester Street was the heart of New York’s Jewish quarter, where vendors sold goods and services from pushcarts. This photograph captured the vibrant energy of a neighborhood well represented in popular illustration and visited often by curious tourists. No doubt the people Alice photographed were also curious, seeing a well-dressed, young woman setting up a camera and disappearing under a focusing cloth.

Weighing turtle, February 1895 [full-frame print and cropped, masked print]. Collection of Historic Richmond Town, 50.015.0845 and 50.015.0848

Alice reworked a busy Fulton Market scene to feature the central figure weighing a sea turtle. In the edited version, she masked the negative, removing the group gathered around the turtle, and printed a single dockworker against a white background. This unique experiment was perhaps the prototype for the “street types.”

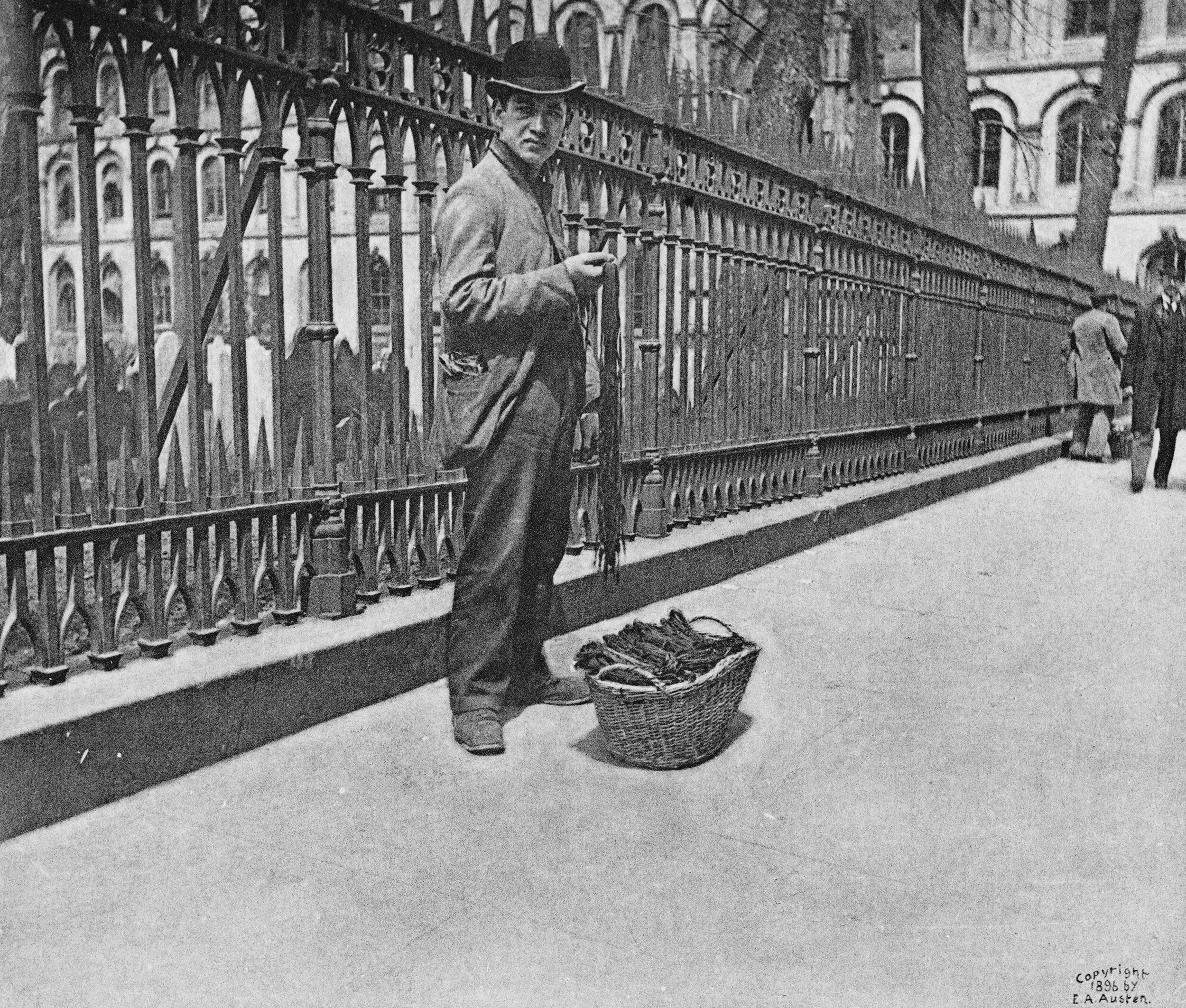

Shoelace Pedler, Trinity Church Railing, April 13, 1896 [silver gelatin printing out paper and Albertype]. Collection of Historic Richmond Town, 50.015.0959 and 50.015.2190

The Albertype Company, a publisher of souvenir books and postcards, printed the “Street Types” portfolio in photogravure, an ink-on-paper process. Although the photogravure was a high-quality form of reproduction, comparing it with Alice’s silver gelatin print reveals the tonal subtleties lost in the process.

The Albertype Company was owned by Adolph Wittemann, a Staten Islander, who asked Alice to represent his company in St. Augustine during the 1897 winter season. Although she did not accept his offer, she kept his letter, suggesting she considered it.

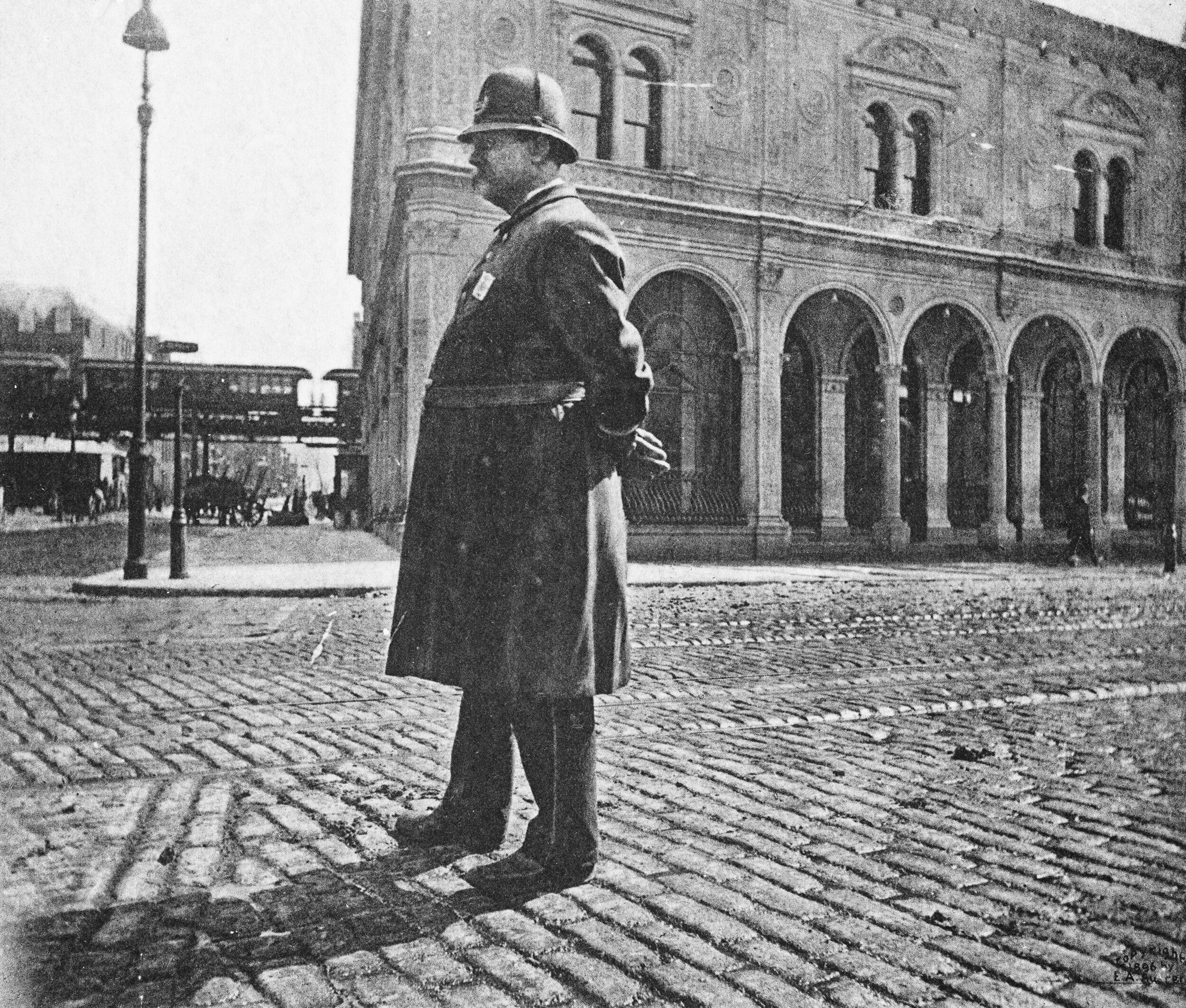

The centuries-old representation of urban tradesmen persisted in 19th-century popular magazine illustration. Alice’s “street types” combined traditional subjects, like rag pickers and organ grinders, with modern ones, like newsboys and bicycle messengers.

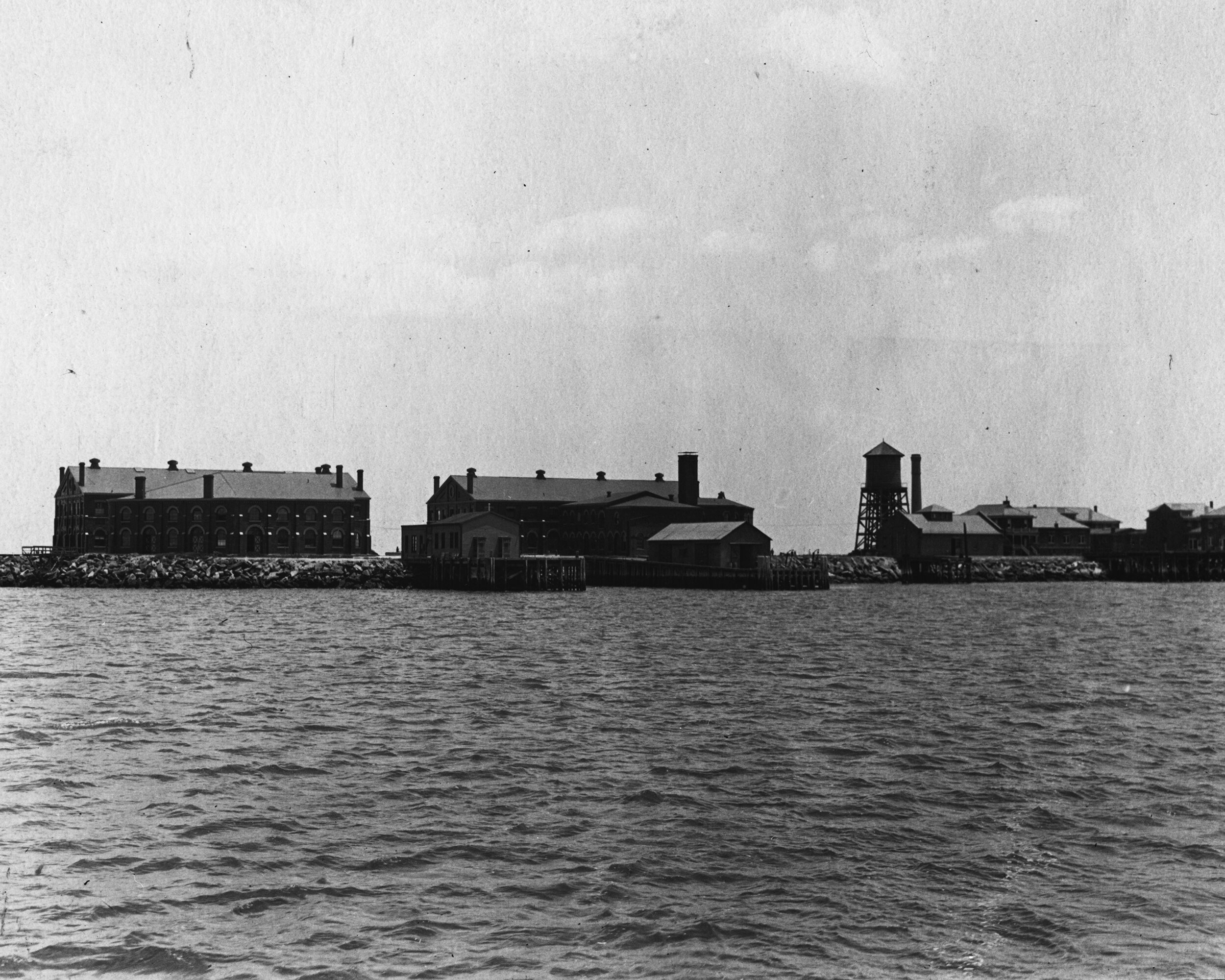

Arriving Immigrants

A three-minute walk south of Clear Comfort along the harbor shoreline was New York’s Quarantine Station, from where tens of thousands of shipboard immigrants were inspected on their way to the newly opened federal entry station at Ellis Island. In 1895, Dr. Alvah H. Doty, a public health innovator, was appointed Health Officer of the Port of New York. He and Alice were neighbors. Early in his tenure, Doty hired Alice to photograph his projects for publication and continued to hire her until his departure in 1912.

Disinfecting boat Dr. Doty & Alvah on deck, July 17, 1896. Collection of Historic Richmond Town, 50.015.5737

Alice photographed Doty and his son on the deck of the James W. Wadsworth, a sidewheeler steamboat that Doty remodeled into a disinfection station.

Cyrene Wadsworth, 1901. Collection of Historic Richmond Town, 50.015.1353

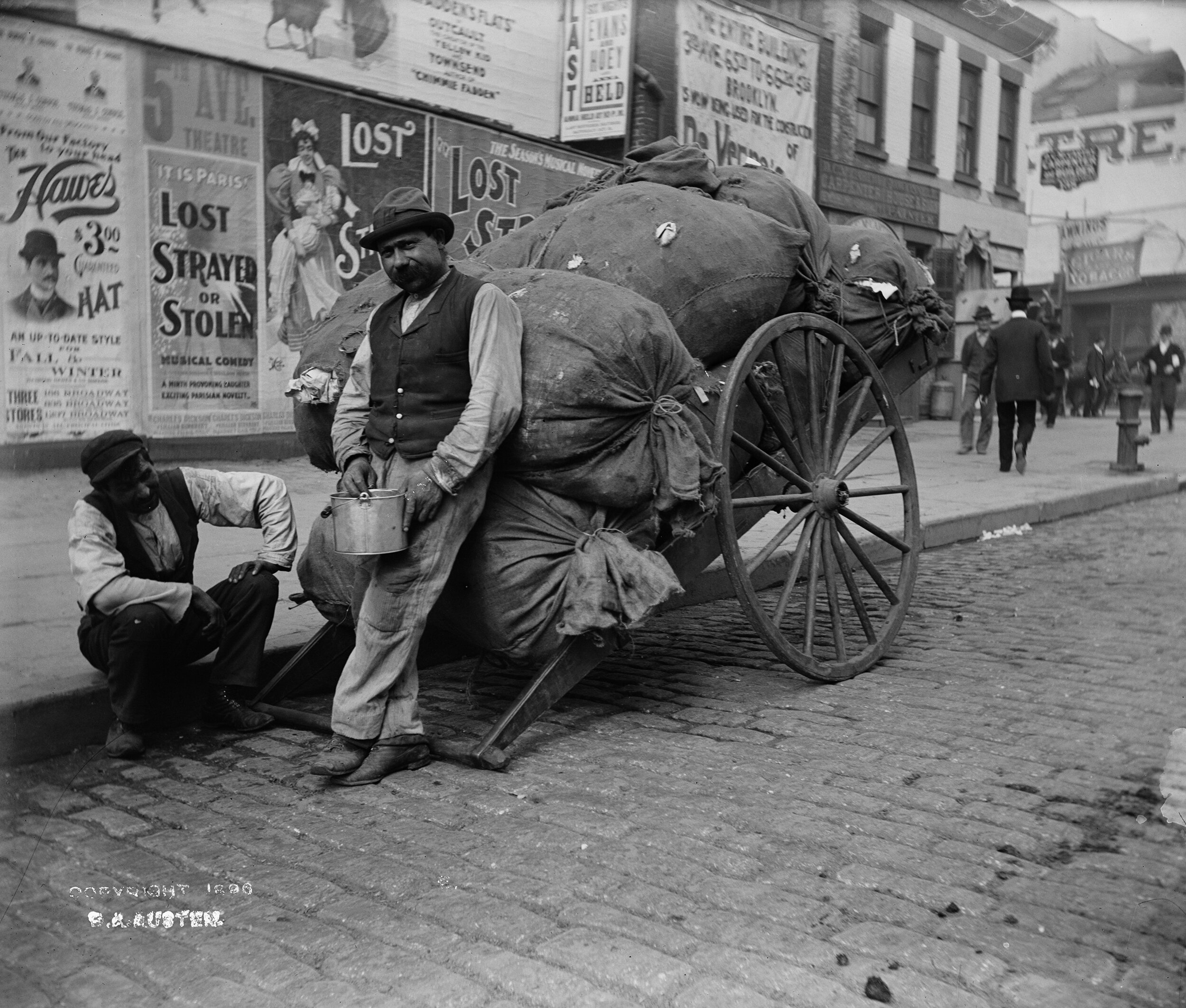

[Quarantine boat James W. Wadsworth], August 25, 1900. Collection of Historic Richmond Town, 50.015.7073

Immigrants suspected of contagion were removed from arriving ships to the Wadsworth, where they showered, and their belongings were disinfected. Here the steamboat approaches the Cyrene, a 2,900-ton British cargo ship suspected of carrying yellow fever.

The Wadsworth stands docked in front of the Quarantine Station near Clear Comfort. The steamboat was fitted with state-of-the-art decontamination equipment, which Alice photographed for Doty’s annual report and articles.

In the 1870s, New York State opened two artificially constructed islands—Hoffman and Swinburne—off the south shore of Staten Island as quarantine facilities for the Port of New York. Under Doty’s administration, the island facilities were expanded and modernized to meet the increasing numbers of arriving immigrants.

Pan-American Exposition, Buffalo, 1901

Alice took numerous photographs for Doty’s multi-media exhibit on the New York quarantine facilities for the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo. The exhibit may have inspired Alice to visit the exposition, where it won a gold medal. Alice photographed the building in which the exhibit was held but not the exhibit itself, which would have required flash.

[Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building, Pan-American Exposition], 1901. Collection of Historic Richmond Town, 50.015.0309

[Electric lights, Pan-American Exposition], 1901. Collection of Historic Richmond Town, 50.015.2326

Like many visitors, Alice was fascinated by the electric lights that lit the fairgrounds at night. Her photographs compare favorably with professional renditions of the spectacle.

E.A.A. & bicycle, n.d.. Collection of Historic Richmond Town, 50.015.2526

Bicycling for Ladies

The 1887 introduction of the “safety bicycle”—with wheels of equal size and inflatable tires—prompted a national bicycle craze. Alice was an early enthusiast. Bessie Strong, a close friend, wrote Alice asking, “What are you doing with yourself I wonder? Probably the bicycle reigns supreme still.”

Staten Island Bicycle Club Tea, End Line of Wheels, June 25, 1895. Collection of Historic Richmond Town, 50.015.0017

In June 1895, Alice and Violet Ward, who had played tennis together for a decade, co-founded the Staten Island Bicycle Club. They established a clubhouse near the ferry in St. George, which offered a meeting place, repair shop and storage facility. In this photograph, members head out for a ride before a benefit tea to raise funds to furnish the clubhouse.

Maria E. Ward, Bicycling for Ladies, 1896. Collection of Historic Richmond Town, 02.005.0047

In 1896, Violet wrote a book, Bicycling for Ladies, “with hints on the art of wheeling, advice to beginners, dress, care of the bicycle, mechanics, training, exercise, etc., etc.” The 200-page book advocates for loose-fitting clothing, physical culture, mechanical competence, and self-sufficiency for women.

Published by Brentano’s, Violet’s book was illustrated with 34 heavily reworked halftones based on Alice’s photographs, but Alice’s name appears nowhere in the book. Daisy Elliott, a fellow bicycle enthusiast and professional gymnast who managed the Berkeley Gymnasium in Manhattan, posed for the illustrations. An 1890 article in Scientific American about the gym was illustrated with drawings after photographs of equipment and exercises, and may have inspired the illustrations for Violet’s book.

[Daisy Elliott on a bicycle], ca. 1895. Collection of Historic Richmond Town, 50.015.2524

"The Correct Position—Leaning Toward the Wheel," Bicycling for Ladies, opp. p. 22. Google Books

To be photographed "leaning with the wheel," Daisy had to balance herself against a pole, which was eliminated by the illustrator.

[Daisy Elliott carrying a bicycle], ca. 1895. Collection of Historic Richmond Town, 50.015.2514

In this photograph of Daisy Elliott carrying a bicycle, she wears "knickerbockers"—loose-fitting pants—that were safer than skirts for bicycling but were ridiculed by conservative critics of the day.

Nine years older than Alice, Daisy was an ardent feminist and a lesbian (although the term was not in popular use). Her 1896-97 letters to Alice indicate that they had a rocky affair. Her last letter, dated January 18, 1898, exemplifies their cat-and-mouse game:

My darling, you don’t know what a brick you are; I simply admire what I saw in you to-day—more still for me to love, and I know how to do that… You have made me believe in your love, you never made it more evident than to-day—and now I am willing to be set aside till you again have time for me.

![Shoelace Pedler, Trinity Church Railing, April 13, 1896 [silver gelatin printing out paper and Albertype]. Collection of Historic Richmond Town, 50.015.0959 and 50.015.2190](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d23a00f53f6300001f811bb/1629059208461-Y9MCTGA1PVRKCU93TZIF/50.015.0959_50.015.2190_aa.png)

![[Quarantine boat James W. Wadsworth], August 25, 1900. Collection of Historic Richmond Town, 50.015.7073](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d23a00f53f6300001f811bb/1633388226701-LI1M3E9SG85Z9SJECUGM/50.015.7073_aa-c.jpg)

![[Quarantine laundry, Hoffman Island], 1901 Collection of Historic Richmond Town, 50.015.1727](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d23a00f53f6300001f811bb/1628773502192-575SAS5VS1B3B9T7SAKP/50.015.1727_aa_slide-4_gray.jpg)

![[Daisy Elliott on a bicycle], ca. 1895. Collection of Historic Richmond Town, 50.015.2524](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d23a00f53f6300001f811bb/1631999582343-NUYJKXBR92DJ1P4JFBO5/50.015.2524_aa_gray-c.jpg)