Long Island Dirt: Recovering Our Buried Past

LONG ISLAND DIRT

Recovering Our Buried Past

By Allison McGovern

Long Island is rich in diverse histories, and archaeology is one way those histories can be explored. Long Islanders understand that their life experiences are shaped by the region in which they live, and that their communities are often defined in relation to each other. In a sense, their identity is tied up within a series of boundaries and relationships—through municipal boundaries like town and village limits; school district boundary lines that sometimes transcend town and village borders; the environment; transportation routes; and other factors. As a result, they have developed bounded senses of community that are not so easily understood by outsiders.

Long Island Dirt is about exploring what we can learn from micro-histories or place-based narratives, investigating how those local narratives might be connected to other sites. This project seeks to develop a macro or regional understanding of Long Islanders’ pasts by connecting people and places though time and space. The exhibit begins with a contextual statement about Long Island’s geography, ecology, and history, provided below as background to the exhibit. Four archaeological sites are then spotlighted: a Montaukett Indian home in East Hampton, an African American home in Huntington, the home of a White, working-class family in Manorville, and the home of an elite White family in Yaphank. These sites were chosen because they represent the lesser-known stories of nineteenth century Long Island. Each provides a glimpse into the lived experience of various Long Islanders before the expansion of its railroad, the marketing of summer resort areas, and the eventual development of the modern suburban landscape. The exhibit ends with a review of archaeological methodology and how this work makes a significant contribution to documenting our past.

Long Island: Understanding the Place and its People

Situated east of New York City, Long Island is an island rich in history, ecology, and culture. Over the last several thousand years, Long Island’s ever-changing landscape has been home to many diverse peoples and communities whose identities have been defined in relation to the landscape. Read more

East Hampton: The Fowler House

The Fowler house was investigated archaeologically in 2018 as part of a renovation of the building. The house and archaeological site help tell the stories of one Montaukett family who was dispossessed of tribal lands in Montauk and established a new home in the Freetown neighborhood of East Hampton in the late nineteenth century.

View this section

Huntington: The Crippen House

Archaeological research at the Peter Crippen house is directed at recovering information about site history, and the experiences of Crippen, one of many southern freedmen who sought work in New York in the early 1800s. His family lived in the house into the late 1900s.

View this section

Manorville and Yaphank: Tenant Farming and Industry

Many archaeological investigations have taken place in Manorville and Yaphank over the past 30 years, although most residents know little about that work. This research has been particularly revealing with the Weeks family, whose extensive properties and businesses provide an ideal window onto 19th century tenant farming and industry.

View this section

Yaphank: W.J. Weeks and his Octagon House

W.J. Weeks built an unusual, octagon-shaped home around 1849 on the cusp of the 1850s architectural craze in New York. Research at this site relates the structure to mid-nineteenth century philosophies of clean living and social reform.

View this section

The New Long Island

Long Island communities faced new changes in the mid to late nineteenth century, when wealthy elites from New York City discovered its beauty and accessibility. The development of summer resort communities, elaborate estates, and hunting preserves altered the landscape and impacted the lives of Long Island residents.

View this section

Outlining the Method

Archaeological investigation at the East Hampton Historical Farm Museum.

Courtesy of Allison McGovern

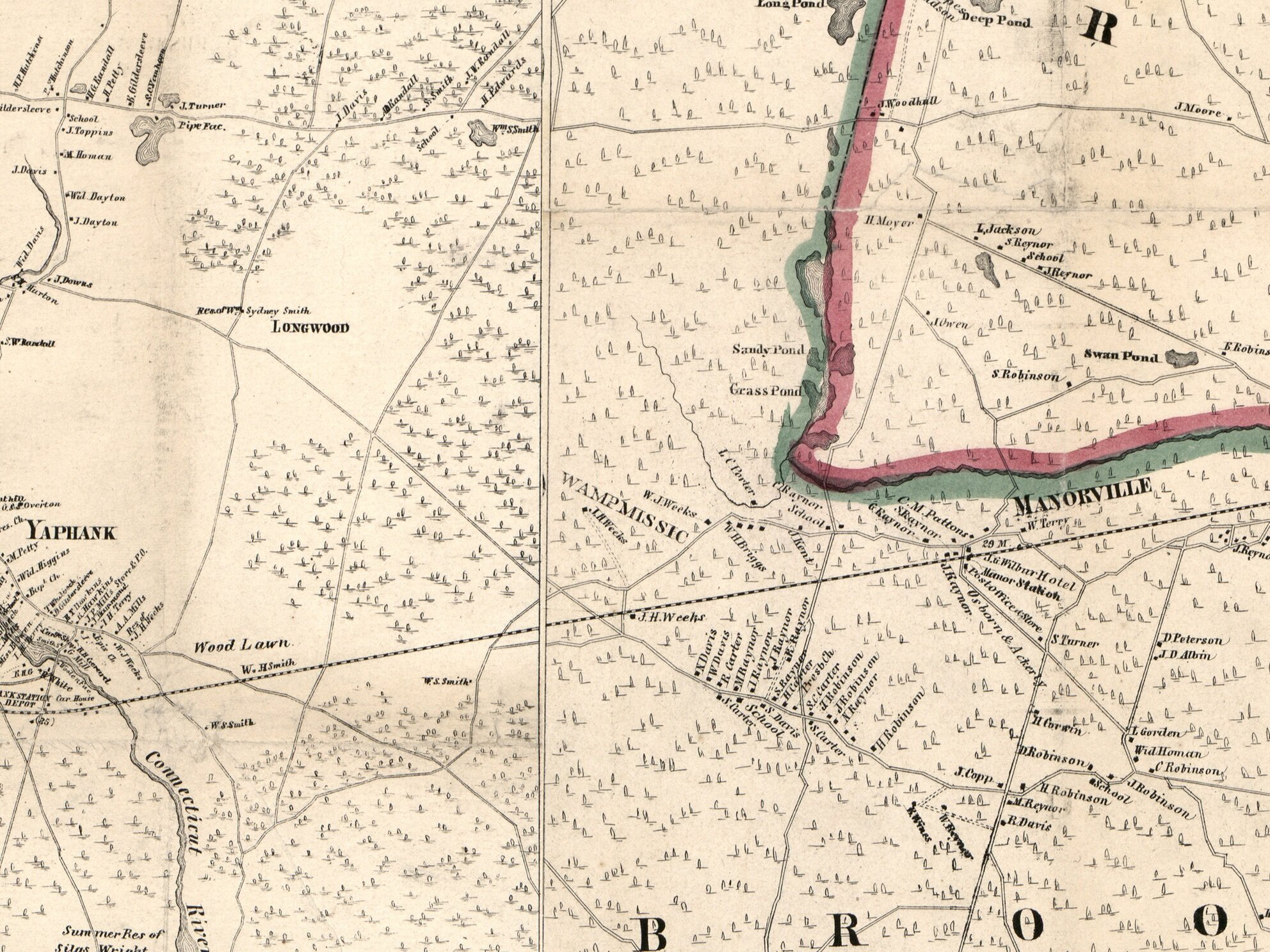

Archaeology is an important process for documenting our past. Historical archaeology, a specialized field of the discipline, relies on multiple resources, researched and interpreted together, to build a narrative of past activity at a site. These include artifacts, features, and data about site formation that are recovered and recorded through excavation (i.e., digging with shovels and trowels). Archaeologists also refer to historic maps for documentation of past land use, like evidence of historic buildings, structures, and roadways. Some illustrate property ownership, or the name of a resident associated with a structure, which can then be referenced against Federal Census data and other documents to reveal of how many people lived at a site, what people did for work, and how they were identified by government officials. For more specific economic information, account books or diaries may be available in the Special Collections sections of local libraries. These resources provide a range of historical information, personal and public, from economic activities to personal family accounts. Interviews and conversations with descendants and local residents are also extremely useful when researching a site. Conversations with various stakeholders can often provide undocumented information about the people who lived at the site. Through archaeology, we can learn about aspects of past lived experiences that might not be readily available through other historical accounts, such as economic strategies; labor strategies; and different attributes of ethnicity, race, class, and gender.

In the United States, most archaeological work is done for compliance purposes, often as part of a series of environmental reviews. It is quite common for archaeology to be done early in the planning of infrastructure projects—such as road construction, new energy initiatives (such as wind or solar farms), or new development projects that involve state or federal review—to determine if proposed development will impact known or potential archaeological sites. Federal, state, and local laws determine and guide the process of reviewing proposed projects and their potential impacts to archaeological sites. This work—referred to as contract archaeology, or cultural resource management (CRM)—often does not mirror the public’s impression of archaeology. However, most archaeologists in the United States are employed in this kind of archaeological work.

Archaeological sites are considered important resources for understanding our past because they reveal information about how humans relate(d) to their environment over time. But while archaeologists are working throughout the country on local and regional sites of all time periods and contexts, most of that research gets buried in what’s called “grey literature”: reports and documents that are reviewed by agency officials, but rarely shared with public audiences. Many recognize that the broader public may be interested in learning more about the work of contract archaeologists and the research generated by it, however. Long Island Dirt is written to share research with the public. It draws connections between local histories through archaeological investigations, providing a more regional approach to understanding Long Island's history.