Alice Austen: The Art and Craft of Photography

Miss Alice Austen and Staten Island’s Gilded Age

by Bonnie Yochelson

The Art and Craft of Photography

Alice’s cameras were wooden boxes with a lens in front and a holder in back that held a glass plate negative covered with light-sensitive, silver emulsion. In this photograph, one of Alice’s cameras faces the harbor, resting on a tripod and covered with a focusing cloth, which Alice placed over her head to compose an image.

4 x 5 inch Premo camera, Rochester Optical Company, 1893-97, 7 ½ x 7 ½ x 8 inches, closed.

Courtesy of Eric Taubman, Penumbra Foundation

When Alice took up photography, it was a fad for the wealthy, and many of her friends tried it, too. She alone perfected the craft, for which she was greatly respected. Alice’s cameras were simple and heavy: wooden boxes with a lens in front and a negative holder in back that held a glass plate coated with light-sensitive, silver emulsion. Exposures were slow, requiring Alice to secure the camera to a tripod and to command her subjects to hold still. To compose an image, Alice placed her head under a focusing cloth, where she could see the scene on a ground glass, albeit upside down. Together, camera, plates, lenses and tripod weighed as much as 50 pounds.

This camera is similar to the 4 x 5 inch camera manufactured by the Scovill Company that Alice acquired in 1890 and became her mainstay.

Making Use of the Pump in Developing, 1911. Collection of Historic Richmond Town, 50.015.7177

On the second floor of the Austen House was a small darkroom where Alice developed her negatives. To make a print, she did not use chemicals in the darkroom but secured a glass negative and sheet of light-sensitive paper in a contact frame, which she placed in direct sunlight. When the image appeared, she stopped the process by washing the print outdoors with ice-cold well water.

Violet Ward & Trude on Terrace Naval Parade, October 11, 1892. Collection of Historic Richmond Town, 50.015.5232

Alice’s darkroom was probably set up by her Uncle Peter, the youngest child of John Haggerty and Elizabeth Townsend Austen. Fourteen years older than Alice, Peter was a chemistry professor at Rutgers College and a proficient amateur photographer.

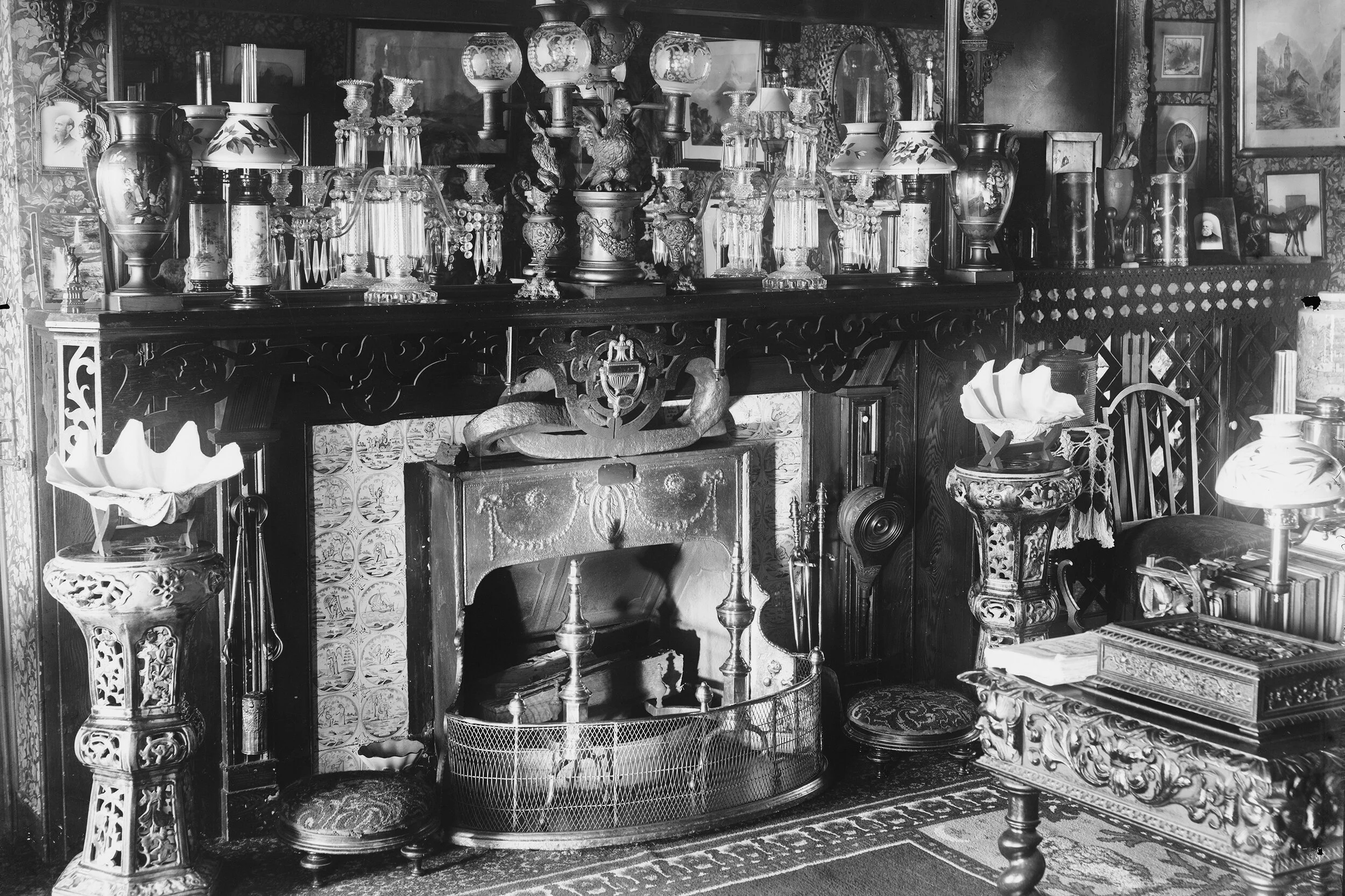

Parlor at home, fireplace, November 14, 1888. Collection of Historic Richmond Town, 50.015.6505

The majority of Alice’s glass negatives were made with either a “full plate” camera, with 6 ½ x 8 ½ inch negatives, or a “detective” camera, with 4 x 5 inch negatives. This photograph shows the “full plate” camera set up on a tripod facing the Narrows, where a naval parade was scheduled to pass. Alice’s friends, Gertrude Eccleston (known as Trude) and Maria E. Ward (known as Violet), sat on a circular bench around a large yew tree watching the parade.

Alice’s meticulously annotated negative sleeves evidence her self study. On the negative sleeve for this view of the Austen House parlor, she recorded the glass plate brand (Carbutt light 25 blue label); subject (Parlor at home, fireplace); light conditions (Fine day, shaded flash light); time of day (10.20 AM); exposure time (11 ½ mins); aperture (Stop 44); lens (Perken); and date (Nov. 14th 1888).

Mrs. Snively, Jule & I in bed, August 29, 1890. Collection of Historic Richmond Town, 50.015.5499

To freeze motion at low light levels indoors, Alice used the newly invented flash powder, which when ignited at the time of exposure set off a small explosion. In this photograph taken indoors at night, the light from the flash reflects off the varnished oak bed frame behind the heads of Alice, her friend Julia Martin (right) and Julia’s friend Eliza Snively (center).

Group on tennis ground, August 5, 1886. Collection of Historic Richmond Town, 50.015.6707

Alice often took photographs of herself alone and in groups. This required her to compose an image under the focusing cloth and then move in front of the camera, releasing the shutter by squeezing a bulb attached to a rubber tube. In this tennis scene, Alice (left) concealed the rubber tube by covering it with tennis racquets.

Mr. Munroe & Nellie in boat on Assabet River, June 13, 1892. Collection of Historic Richmond Town, 50.015.6138

In addition to Alice’s uncles Peter Austen and Oswald Muller, two other family members were skilled amateur photographers. One was Alfred Munroe, seen here with his niece Ellen Middleton Munroe Austen (Alice’s Aunt Nellie) boating near Alfred’s home in Concord, Massachusetts. Alice’s photograph recalls the masterful compositions and delicate light effects of Alfred’s Concord landscapes.

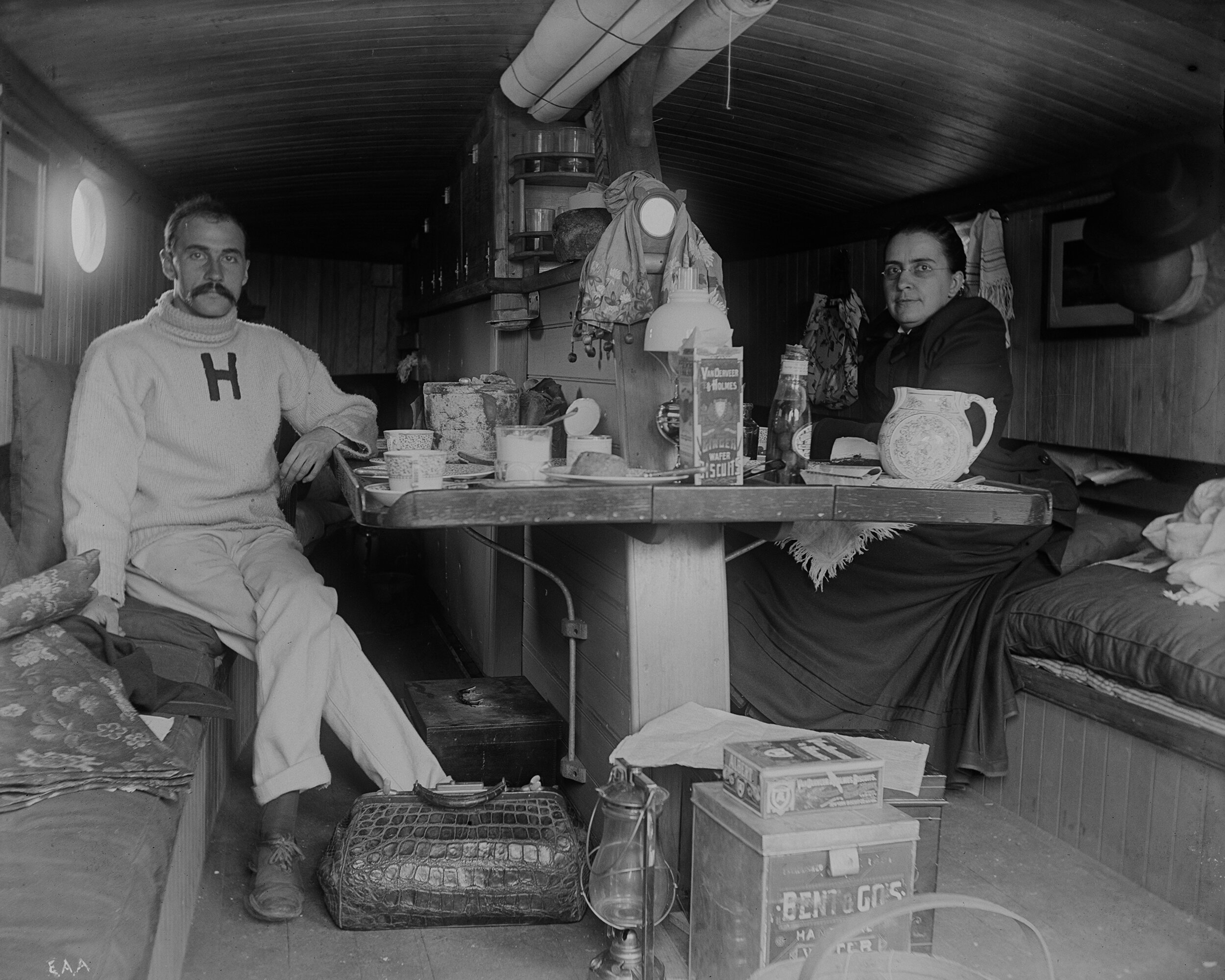

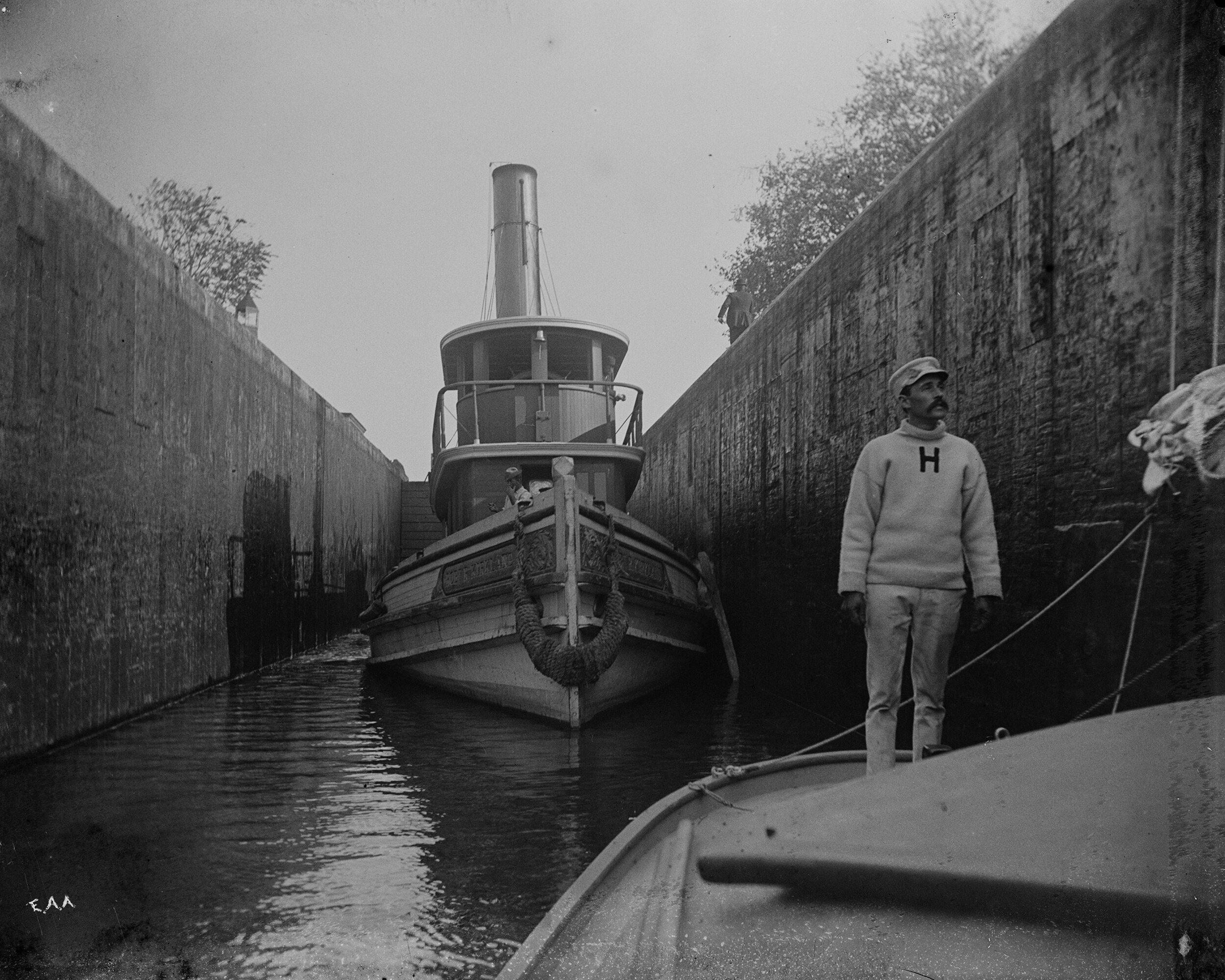

Another accomplished amateur photographer in the family was Ralph Middleton Munroe, Nellie Austen’s brother. Ralph was also an innovative yacht designer, and Alice and Nellie accompanied him as far as Annapolis on the maiden voyage of his yacht the Wabun from Staten Island, where the boat was built, to Coconut Grove, Florida, where Ralph lived. Both Alice and first mate Thomas Quincy Browne, Jr., nicknamed “Butterball” (seen here with an “H” on his sweater), took photographs on the voyage. Only Alice’s came out well.

By the 1890s when Alice had fully mastered her craft, amateur photography clubs began to experiment with pictorialism, which promoted the idea that photographs should resemble drawings and paintings. Alice was not active in local clubs and showed no interest in the new trend. Only occasionally did she submit prints to competitions or exhibitions.

Alice showed her work primarily to friends and family. When she went visiting, her picture-taking became a group activity, and she sent prints to the people she had photographed. She lavished great care on prints which she compiled in albums, and often gave them as gifts. Shown here are four prints from an album of 38 views of Clear Comfort, which showcase Alice’s exquisite control of lighting and composition.