Long Island Dirt: East Hampton: The Fowler House

Long Island Dirt:

Recovering our Buried Past

by Allison McGovern

East hampton:

the FOWLER HOUSE

The George and Sara Fowler house is located in the town of East Hampton. The home of a Montaukett family between the 1880s and 1980s, its materials are fairly recent in terms of archaeological context and the site has the benefit of descendant connections. That is, there are people whose memories (as kin and friends, residents and neighbors) can be connected to the space and the people that once lived at the site.

The Fowler house is a Town Landmark. In 2018 as the house was undergoing renovation, an archaeological investigation was directed at the interior of the structure to explore questions of architectural construction and structural dating. But the archaeological data—along with the collaborative process—shed light on the politics of research and history-making at the site.

The house and property, which was home to George and Sara Fowler, their children and extended family, are historically significant for their potential to yield historical information about Montaukett lived experience from 1885 through 1980. George Fowler was a Montaukett born and raised at Indian Fields, the Montaukett reservation and ancestral village in Montauk. In the 1880s, as a resident in his parents’ home at Indian Fields, he and his siblings were dispossessed by businessman Arthur Benson, who purchased more than 10,000 acres of Montauk land at public auction. According to a Town restriction that accompanied the sale, Benson was expected to respect the rights of the Montauketts to live at Indian Fields in perpetuity. However, Benson employed local agents to assist him in negotiating the sale of individual Montaukett residency rights to him, in exchange for small plots of land in Freetown. Some of the Montaukett homes were moved from Montauk to Freetown, and the rest were burned. Descendants remember the Fowler house as one of a few homes that was moved from Indian Fields to Freetown. But recently, archival documentation has been privileged over historical memory, making the Fowler house an artifact of history-making and challenging the power of oral history, and questions have developed regarding the age and history of the Fowler house: was it moved from Indian Fields, or moved from elsewhere in East Hampton, or built on site by Benson for Fowler.

Montaukett Indians in 1924. Courtesy of the East Hampton Library, Long Island Collection

Because the house was lived in at its Freetown location by only Fowlers and descendants, the integrity of the house and its associated archaeological deposits are uniquely “intact”. There was no stone or brick foundation, as the house sat on field stone corners; and there was no cellar or basement. These were features that we were looking for archaeologically. Although some structural changes were made during the twentieth century (including the south addition, porch reconstructions, and patchwork stabilization to the interior walls), no substantial changes have been made. Even through the twentieth century, minimal utilities were introduced to the site: electrical lines were visible throughout the house (and an electrical submersible pump was installed in the kitchen to provide running water through the sink), but there were no bathrooms in the house, no connections to public or well water, and heating was provided by a centrally located stove. These were the conditions of the house when it was seized by Suffolk County for taxes owed in the 1990s after the last descendant and resident of the house, Leonard Horton (George and Sara Fowler’s grandson), had died in 1986.

As the house was in the process of structural renovation, a concern was raised that buried archaeological deposits would be under threat of disturbance from the construction work. For this reason, members of the Friends of Fowler advocacy group requested an archaeological investigation of floor deposits and subsurface architectural contexts, as these would eventually be sealed and/or disturbed by structural restoration.

Archaeology at the Fowler House. Courtesy of Allison McGovern

One of the goals of archaeology was to attempt to sort out the issue of house construction. Because the house was constructed of a mix of eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth century construction materials, it proved difficult to attempt to date the house. However, the archaeological work sought clues through site formation processes to discern whether the house was constructed on site or relocated onto the site. Our greatest challenge was the ground disturbance caused by construction workers who had already started the renovation process by stripping the historic fabric from the building, raising the structure, and installing concrete footings to the areas where a builder’s trench might have been. However, through analogical reasoning in historical archaeology archaeologists were able to provide more information to support the thesis that the house was moved to this location, rather than built originally on site.

East Hampton Historical Farm Museum. Courtesy of Allison McGovern

In fact, it was not uncommon for houses to be moved through East Hampton in the late nineteenth century. Just a half mile to the south we can find another house that was moved to its current location in the late nineteenth century. This is the Jonathan Barnes-Selah Lester House which was moved to this site in 1874. Like the Fowler house, this house sits on field stone corners and lacked a cellar (until the twentieth century, when a partial basement was dug for heating and utilities).

Archaeologists also examined the dimensions of the Fowler house, and compared them to a “quitclaim” document between Arthur Benson and George Fowler. The quitclaim document, shown below, promised Fowler and his heirs would receive $240 annually and a 1½ acre parcel at Freetown. It also outlined the dimensions of a house that would be provided at Freetown in exchange for Fowler’s residency rights at Indian Fields.

“adjoining the homestead of George Bennett upon the Southeast side and the Fire Place Highway…Also a dwelling house to be erected upon said land 14ft square with a kitchen + bedroom 7ft + 8ft each, 12 foot posts the house + bedroom to be finished, and furnished at a cost not to exceed $50, and $50 to be paid him when this bargain is consummated.” It goes on to say “Agrees to relinquish all his right title and interest to Montauk excepting the annuity as before mentioned”

The Fowler house measures 15 feet by 21 feet (prior to the addition of a 8.2 by 8.2 feet extension which was added after 1922 and a front porch measuring 7.5 by 15 feet). While the dimensions of the house do not correspond with the house promised in the Benson-Fowler agreement, it does seem to match with the archaeological footprint of a house at Indian Fields: William and Sara Fowler’s home, or George’s childhood home. That house, constructed around 1840, measured 15 by 24 feet and had a dry-laid fieldstone foundation, but no cellar.

Archaeological investigation at Indian Fields, c.1975. Courtesy of Suffolk County Parks Division of Historic Services

Rather than prove that the house was moved to the site, the archaeology presents data that challenges the idea that the house was built on the site according to the agreement drawn by Benson’s agents. First, the dimensions of the house as described and house as measured are inconsistent, and secondly the absence of a stone foundation argues against on-site construction. But in addition to addressing the architectural questions through site formation processes, the archaeology gathered information about human lived experience at the site.

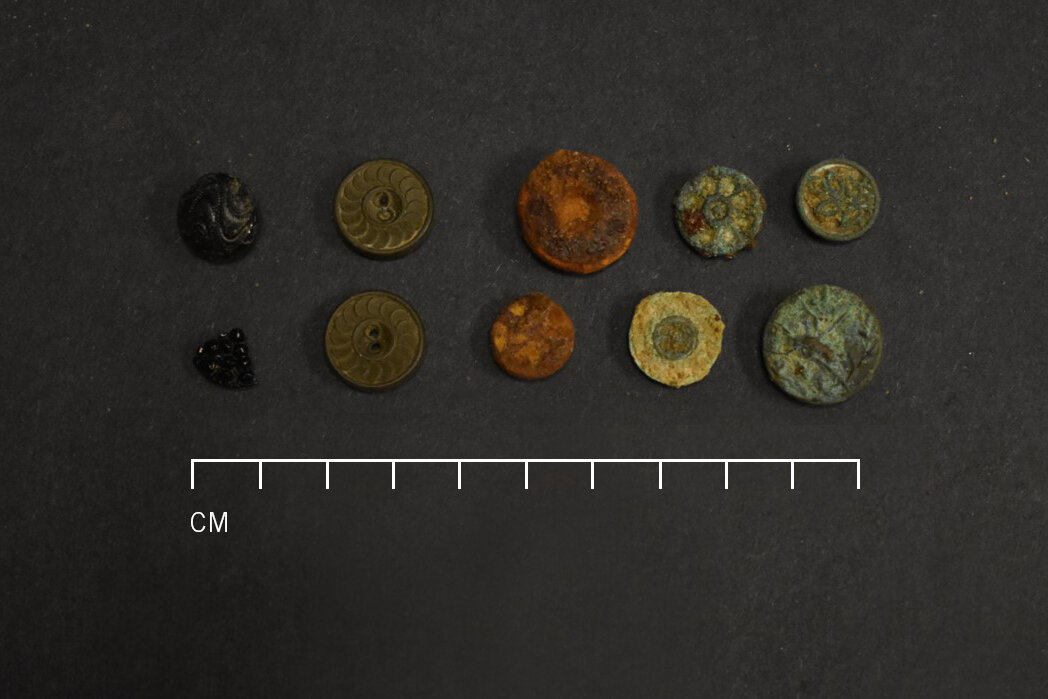

The richest location of archaeological data was the kitchen. In addition to ceramic fragments, bottle glass, and animal bone, an abundance of buttons was recovered: glass, metal, vulcanized rubber, and notably shell—quite a diverse selection of shell buttons.

We do know from descendants’ histories that Sara and her daughters Eliza and Marguerite were skilled at sewing, and when the house was “discovered” in 2014 by preservationists, there was a sewing machine still upstairs.

There were also close to a dozen marbles, porcelain doll and child’s tea set fragments, and a slate pencil fragment. The remnants of toys and gaming pieces are indications of family life—the presence of children, and even adult leisure activities.

Fowler’s house kitchen prior to renovation. Courtesy of Allison McGovern

Prior to the gutting of the house for renovation and prior to archaeological investigation, the kitchen included an electric stove and a sink that was not connected to municipal water. The Fowler family adapted the site to suit their needs, as they connected to electric and installed an electric submersible pump to bring water to the sink. Gray water was then discarded into a brick dry well that was constructed beneath the rear wall of the house in the kitchen. So even in the mid-to-late twentieth century, the residents were never connected to municipal water systems, but rather used this as a residential strategy, still without a bathroom in the house.

The archaeology revealed a discrete archaeological context from c.1885 to c.1930s. The installation of an asbestos tile floor in the 1920s or 1930s sealed any gaps in the floor resulting in minimal artifacts dating to that time. Around that time, the side extension was constructed on the south elevation and the front porch was re-designed with a small gable roof. Although the Town’s renovation plan was to return the structure to its pre-1930 construction, the post-1930 modifications are equally significant in understanding how the Fowler family modified their home to fit the needs of their growing, extended family. The retention of descendants’ memories is also key for remembering and understanding these reconfigured spaces, even if they have since been removed for the sake of historic reconstruction. Mr. James DeVine, for instance, recalls how the home was organized and how spaces were utilized by the family and its visitors.