Long Island Dirt: Manorville and Yaphank: Tenant Farming and Industry

Long Island Dirt:

Recovering our Buried Past

by Allison McGovern

Manorville and Yaphank:

Tenant farming and industry

Manorville and Yaphank have been the subject of archaeological research on case-by-case basis since the inception of cultural resource management (CRM) practice, though most residents of these areas know little about that research. Most of the archaeological research has been done piecemeal for environmental review of development projects. Through these investigations, a range of archaeological sites have been identified, including industrial sites (the Homan mills complex on the Carmans River), residential sites, and pre-Columbian Native American sites.

Archaeology has been particularly revealing in relation to the Weeks family, a prominent family that settled in present-day Yaphank in the nineteenth century. James H. Weeks, born and raised in Oyster Bay, had married Susan Maria Jones of Cold Spring Harbor. In 1828 they moved to Yaphank (roughly 35–40 miles east of the Oyster Bay-Cold Spring Harbor area), which was called Millville at the time, with their young son William Jones. Susan Maria’s sister Eleanor was living nearby, as she had married William Sidney Smith, heir of the Longwood Estate which was located roughly six miles north of Millville. James Weeks had purchased 9,000 acres of land in Wampmissic from William Sidney Smith for a cordwood business in 1828. An 1838 map of the area suggests that the Weeks family lived in a house on the west side of Main Street at that time. Then in 1839 James Weeks purchased 56 acres in Millville north and east of the mill complex at the east end of Main Street. The Weeks family settled into their home, called the Lilacs, around that time.

James H. Weeks and Susan Maria Jones. Courtesy of the Yaphank Historical Society

A grist mill, a lumber mill, and a woolen factory operated on the Carmans River at the east end of main street, and an additional mill complex operated at the western end of Main Street along with a blacksmith, wheelwright shop, printer, and many other businesses lining Main Street in between. Smith and Weeks were business partners in many of the industries there, including the mills (with Robert Gerard), in addition to being brothers-in-law through marriage. A review of account books at the Brookhaven Town Historian’s office suggests that Smith also supported several other businesses that were partnered by Weeks and Youngs proprietors from Oyster Bay and Cold Spring Harbor, who also happened to be connected to him through his marriage with Eleanor Jones. William Sidney Smith and James H. Weeks were also instrumental in bringing the railroad through central Long Island.

Gerard Mill in Yaphank; the Homan Gerard house is visible in the background. Courtesy of the Yaphank Historical Society

The Weeks and Smith families owned extensive properties and businesses. An 1858 map shows two properties owned by James H. Weeks (in addition to his home site), one property owned by W. J. Weeks (in addition to his residence), and three properties owned by William Sidney Smith (in addition to his Longwood estate). Archival research reveals that the additional properties were rental properties.

William Weeks’s diaries provide periodic accounting of his cordwood business. In 1851, Weeks wrote “Father + I went in wagon to Wampmissic to select some place for Akerly my tenant to begin to cut wood.” Weeks would travel to Wampmissic several times a week to meet with Akerly, a cordwood farmer who worked for him. The wood was sold as fuel to the Long Island Rail Road, of which William’s father James was one of the original Commissioners. Based on the diary and a review of Federal Census data, it was Akerly who lived in the house that is illustrated as owned by W. J. Weeks on the 1858 map.

Maps, census records, and other historic period documents indicate that the house was called the “Yellow House” by William Weeks. It was built between 1830 and 1840 and probably abandoned by 1880, if not a decade or so earlier. During most of this period, the house was occupied by a tenant farmer and laborer named Edmund Ackerly and his family.

Edmund Akerly is first documented in the 1840 Federal Census, working in agriculture and the head of a household comprising him, his wife, and three young daughters. By the time of the 1850 census, the Ackerly family had grown to include daughters Mary, Matilda, Gerusha, Harriet, and Angeline, and sons John and Lewis, in addition to Edmund and his wife Julia. Akerly’s employment for William in the 1850s is documented in Weeks’s diaries, but at the time of the 1840 census William was away at college. It is possible that Akerly was initially employed by and renting from William’s father James in 1840, though there is not documentary verification of this.

1840 Census page. Courtesy of Ancestry.com

Akerly’s activities outside of cordwood counts generally go unreported until February 26, 1853, when Weeks wrote “I went to Wampmissic on horseback + thence to the county road to find a place for Akerly to cut wood- found him at the house, abed, + still under the effects of a debauch.” Akerly’s alcohol consumption apparently interfered with his work, and this did not go unnoticed as Weeks reported Akerly’s condition four times during his visits in February and March of 1853.

By 1867, the Akerly family was no longer living in Weeks’s rental property, and the house may have been occupied by a series of renters who are not well documented. Over the next few months, Weeks recorded several visits to Wampmissic to make repairs to the house and clean up the property. Interestingly, the archaeology does not reveal any house-cleaning episodes that might date to this time.

Archaeological research presents an opportunity to contrast the Akerly family’s daily lived experience with the documented lived experience of the Weeks family. The experiences of Weeks and Akerly are compared, as they are thought of as landlord and tenant, employer and employee. According to census data, William Weeks and his father James H. Weeks were among Yaphank’s most prosperous residents during the mid-nineteenth century. The value of William’s real and personal estates grew from $4,900 in 1860 to $15,000 in 1870. In contrast, the Ackerly family appears to have been of extremely modest means. The 1850 and 1860 censuses indicate that Edmund Ackerly did not possess any land or even personal estate (at least, none worth noting).

Nineteenth century farmers sought to produce more than would meet their basic household needs, as their agricultural surplus could be sold. Their participation in the market economy would allow them access to goods obtained through local and global markets, such as ceramic dishes and glassware, foods they couldn’t otherwise produce on their farm, global commodities like sugar, coffee, tea and alcohol, and personal items like shoes, jewelry and pipes for smoking tobacco. Traces of these items can be recovered through archaeology, and they can reveal interesting social and economic details.

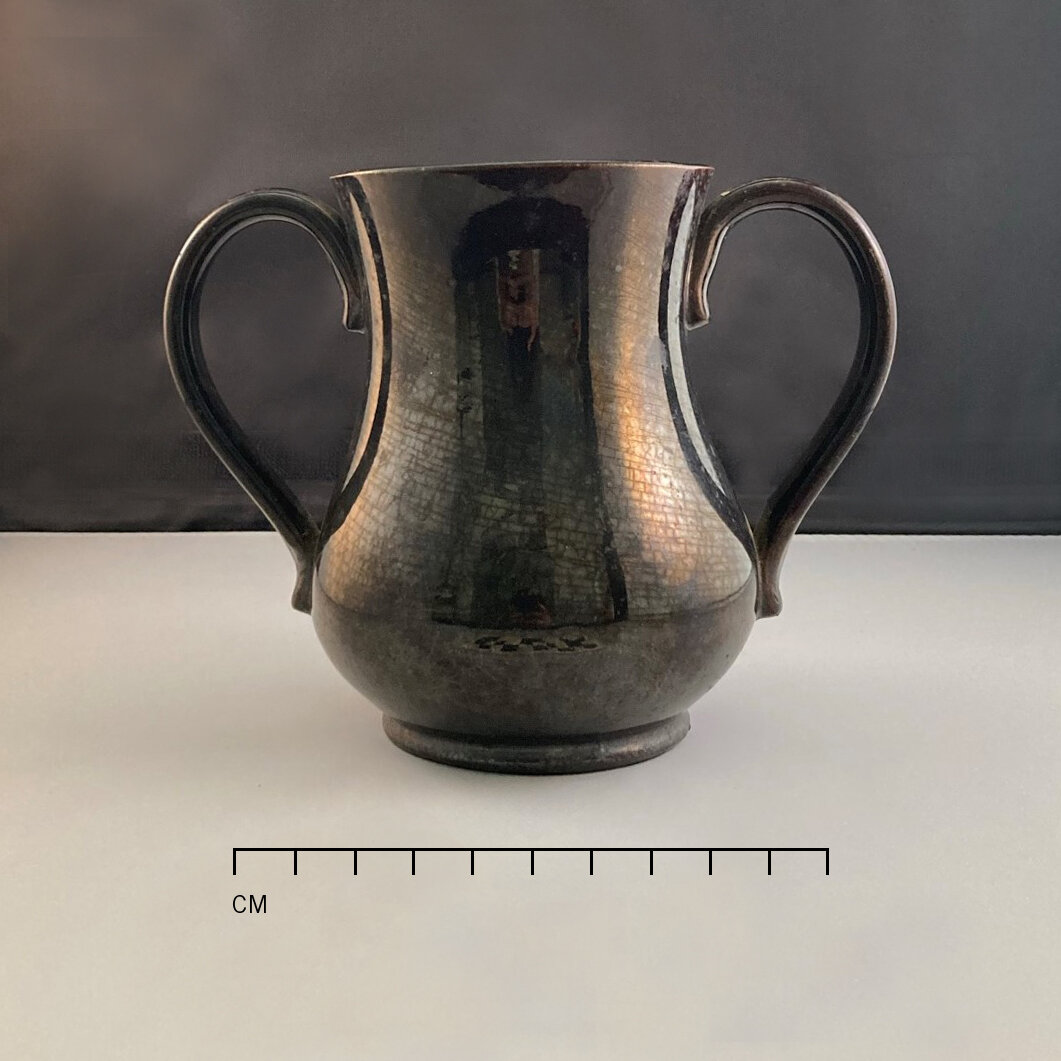

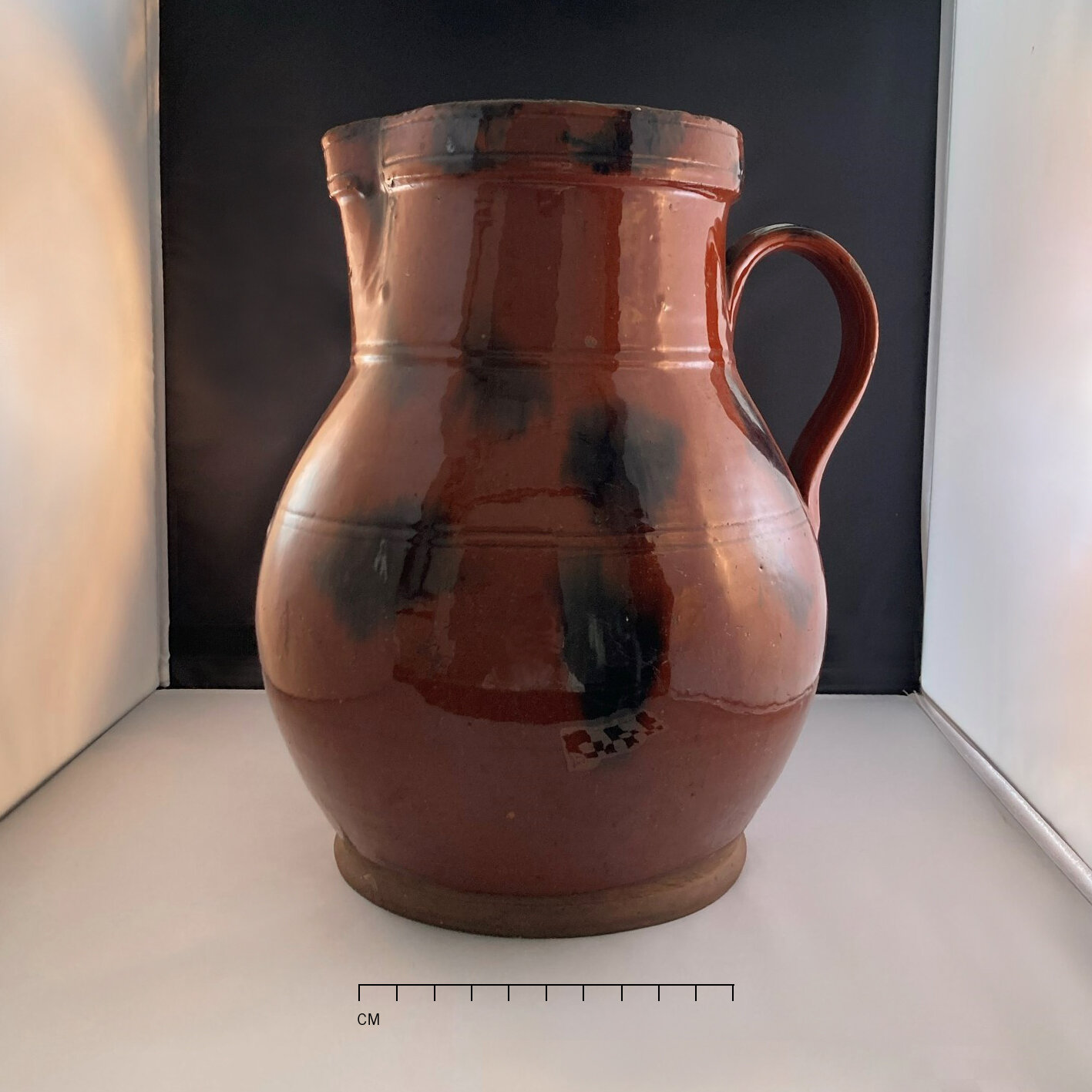

The arrival of the railroad in 1844 opened the New York City market to Long Island farmers and spurred the cordwood industry. The Weeks families and their tenant laborers were farming to meet household needs and to participate in the market economy. The recovery of some ceramic types, food remains, and other types of artifacts demonstrate the Akerlys’ participation in the market economy. They inform us about consumer choice, and they tell us about economic strategies. For instance, some artifacts like decorated pearlware teawares and clay smoking pipes, were imported and purchased at local stores. Other household needs were apparently met locally. Local strategies are represented by utilitarian redware kitchen vessels for the storage and preparation of foods which were most likely produced on Long Island (like the vessels shown here from Preservation Long Island’s local redwares collection). Shell fish consumption, which could have been purchased or gathered locally, is another local strategy revealed by discarded shell at the site.