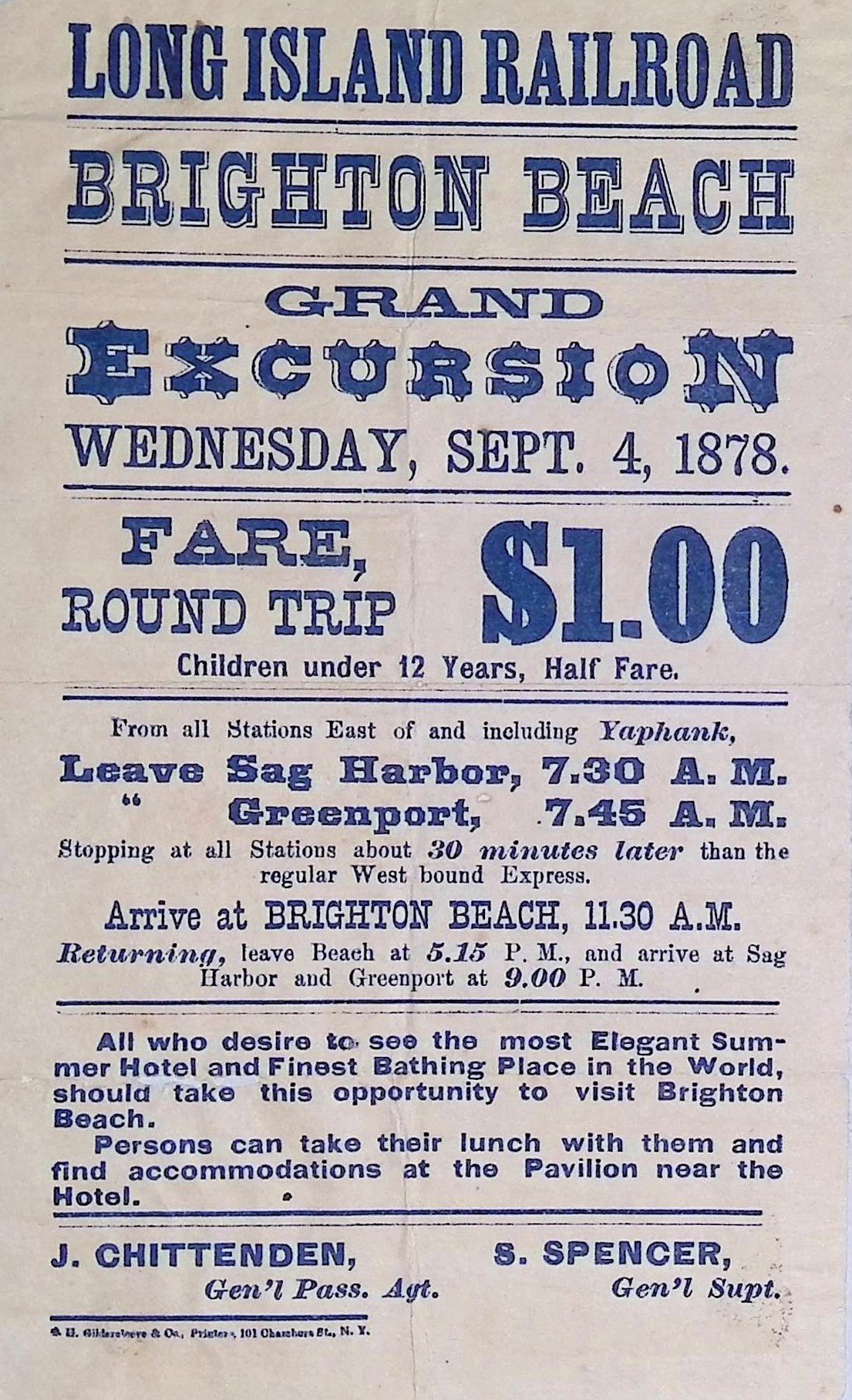

Rapid Transit in the Steam Age: Another World

The Dawn of Rapid Transit in NYC: The LIRR in the Steam Age

by Elizabeth K. Moore

Another World

Tank engine circa 1888 at Woodhaven Junction. Arthur Huneke collection.

“Type of the modern--emblem of motion and power--pulse of the continent,” Whitman wrote of the steam locomotive, which shaped and regulated the accelerating tempo of a mechanical century.

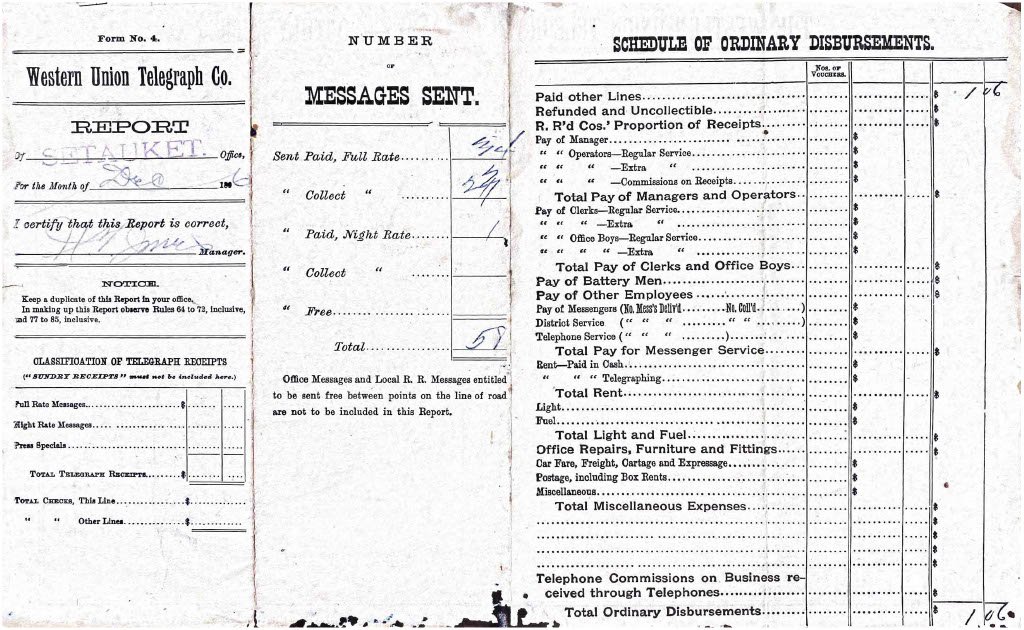

Intersecting railroad lines compelled synchronized movements and clocks, leading to the system of time zones. The network of telephone and telegraph lines strung up along their tracks laid the foundation for modern telecommunications networks and law.

The railroad, contended philosopher Jacques Barzun, "is probably our greatest mental and moral achievement,” the "first great embodiment of modern organization — that prophetic coordination of space, time, matter and men which we now consider the most natural thing in the world."

Boarding a train from Creedmoor Rifle Range, Queens Village, 1899, George E. Stonebridge. New-York Historical Society.

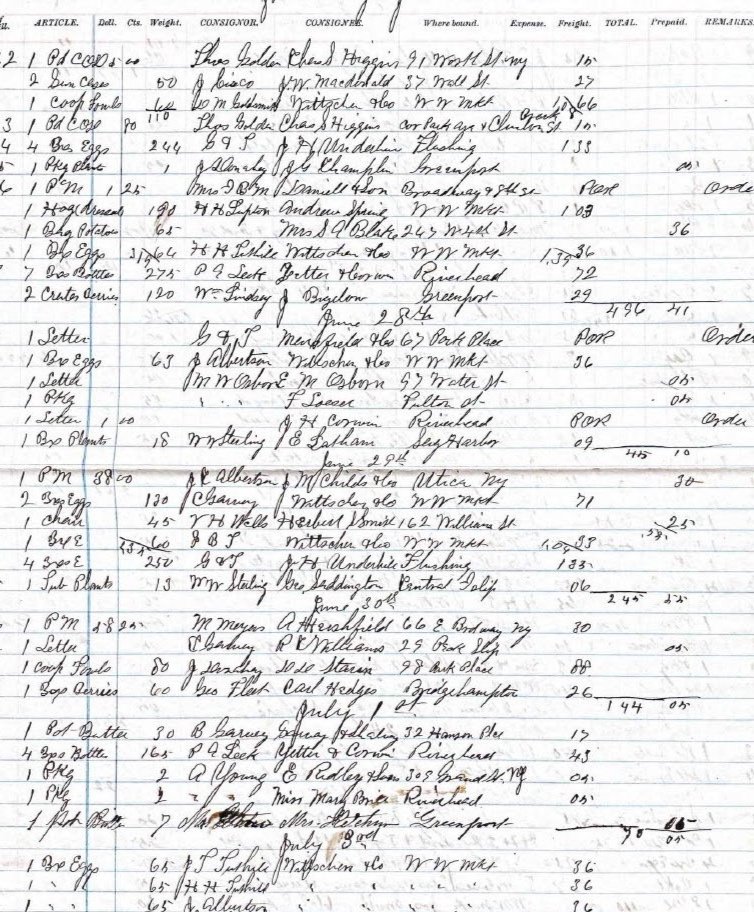

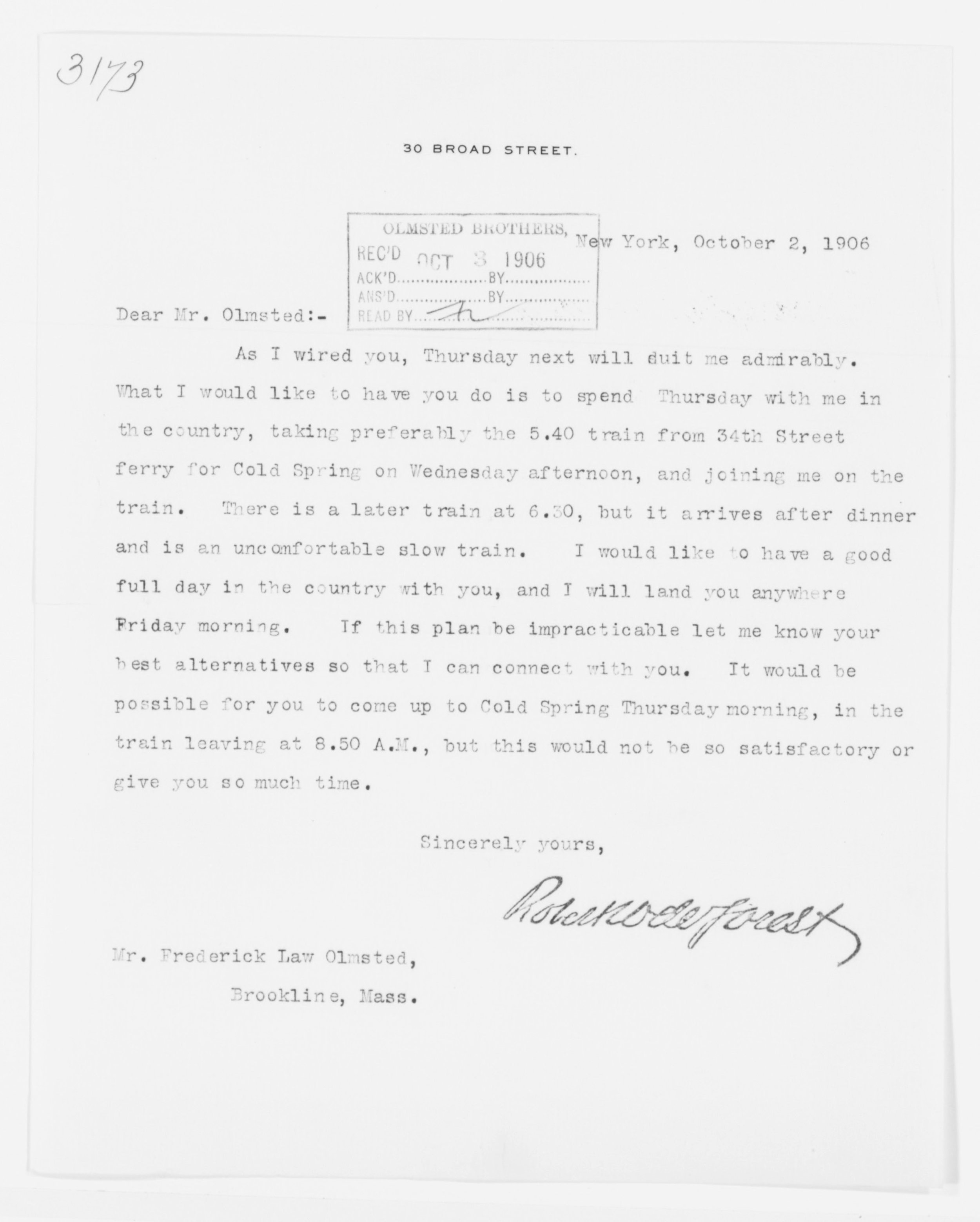

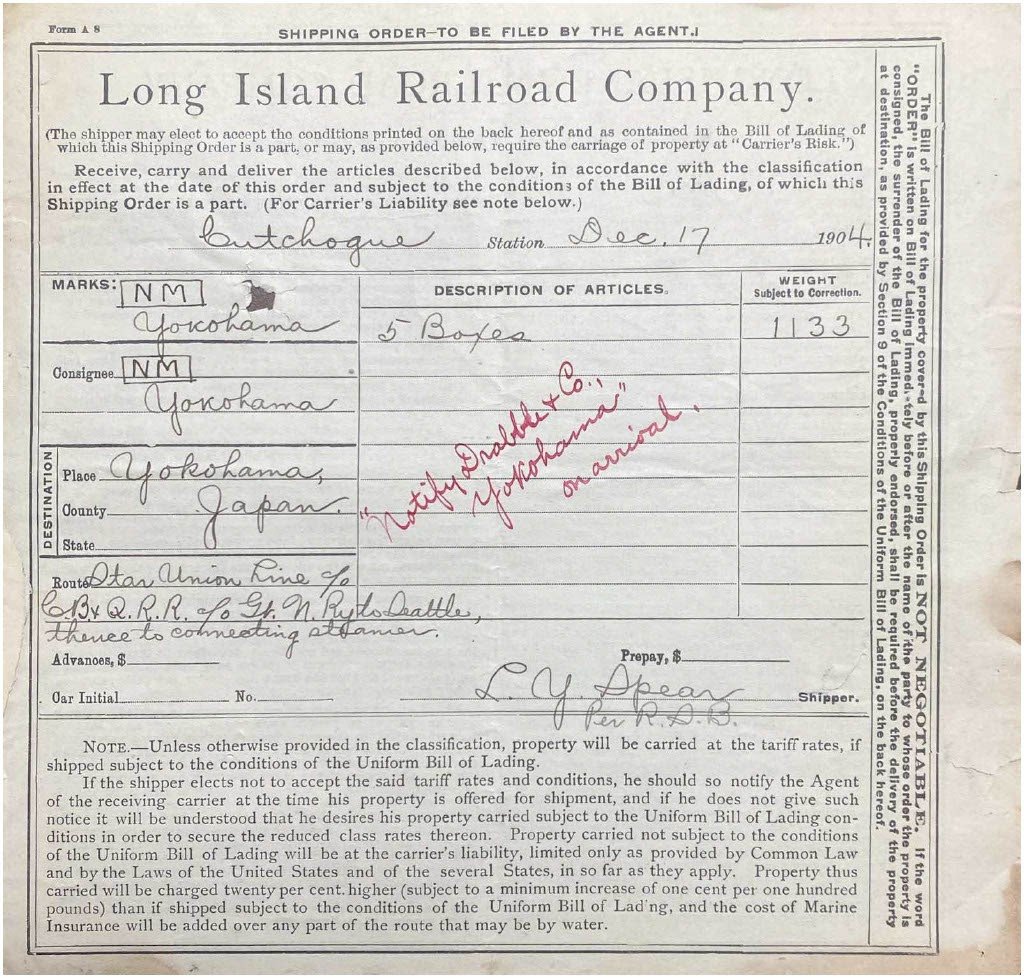

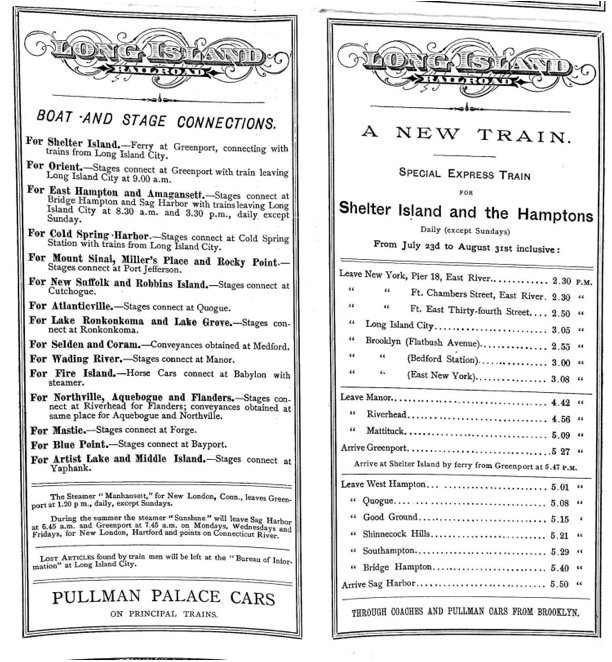

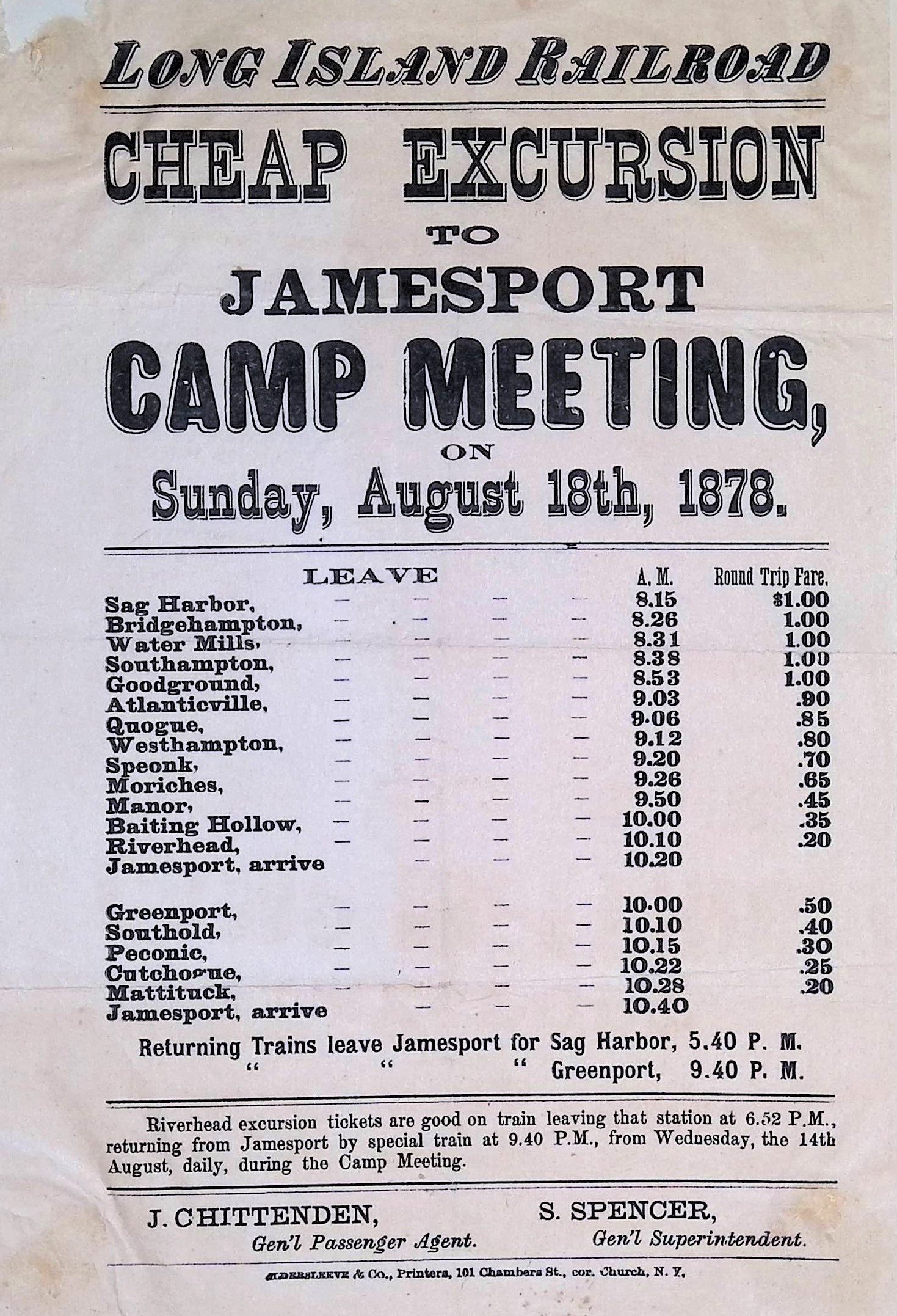

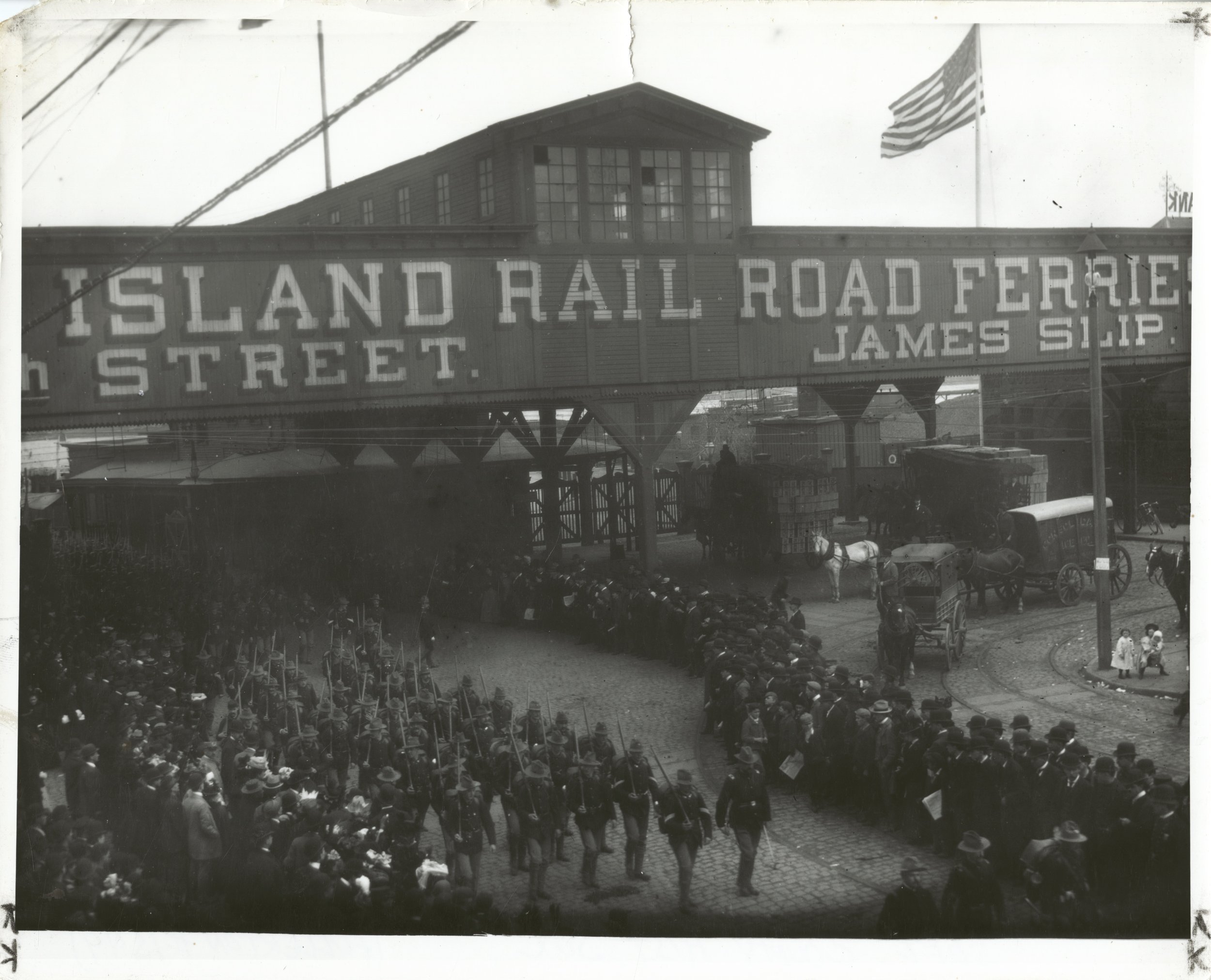

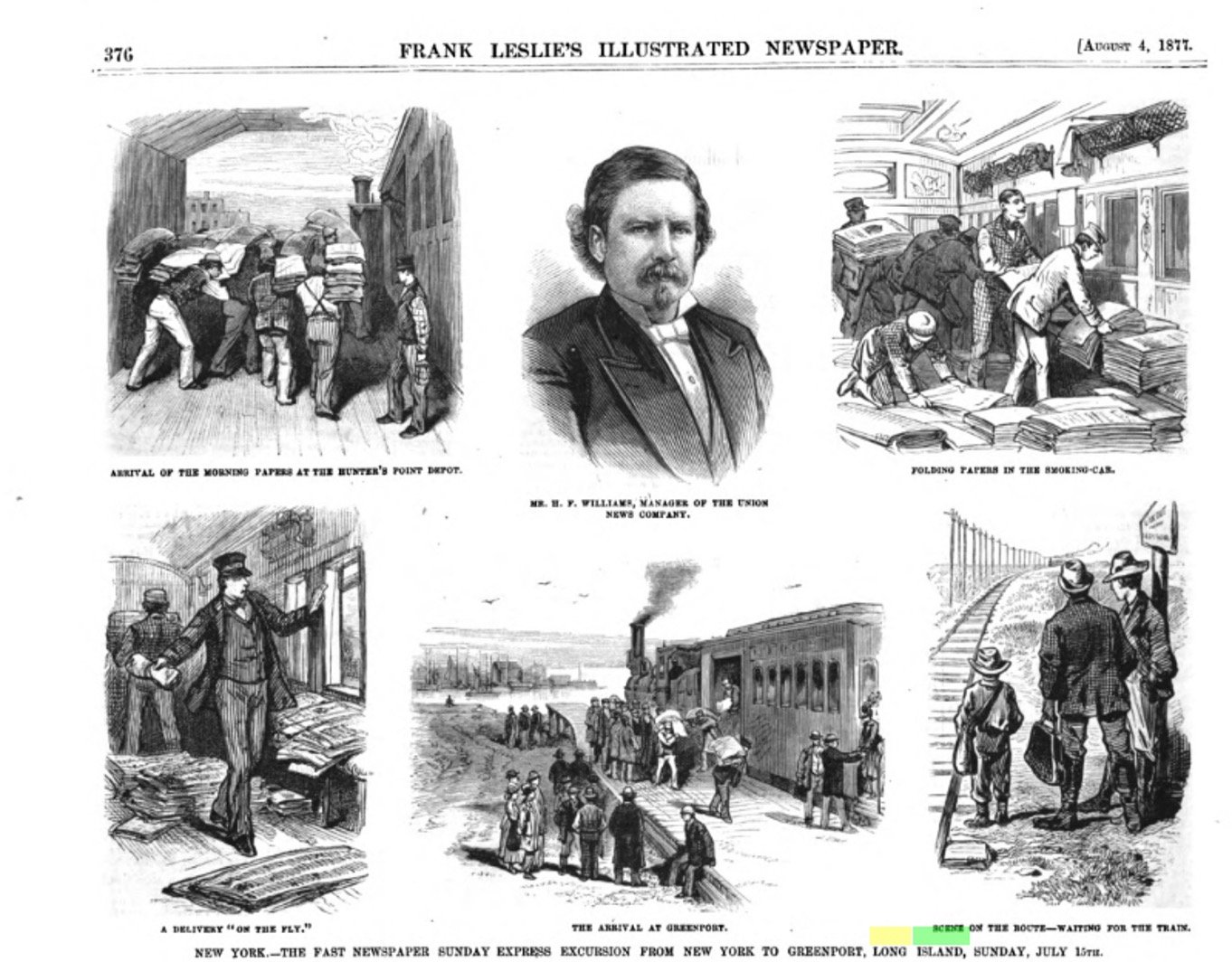

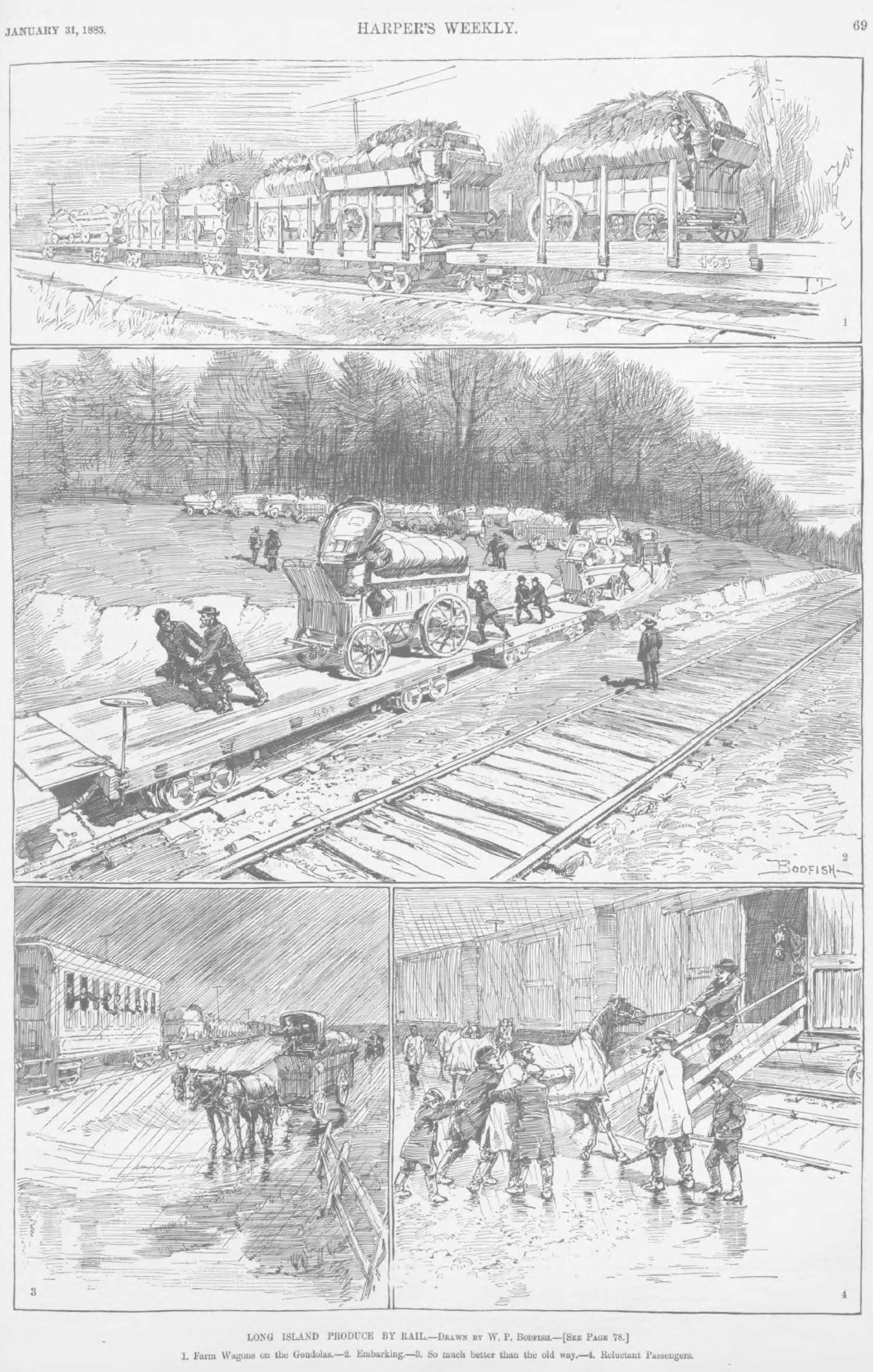

More prosaically, and not always on schedule, Long Island’s steam locomotives hauled milk to the city and coal to the suburbs. They drew special trains for Cypress Hills funerals and Locust Valley asparagus and East End cauliflower, and special trains for President Theodore Roosevelt, and for horse races at the Fashion Course. They carried militiamen and their wives home from shooting parties at the Creedmoor Rifle range, and carloads of ice to William K. Vanderbilt’s South Shore estate, and carloads of food scraps from thousands of dinner guests at Austin Corbin’s Manhattan Beach hotels, bound for hog farms in the east. Some steam trains carried polo ponies and pleasure mounts to Gold Coast estates; others carried farm horses and wagon loads of vegetables to New York street markets. Newspaper trains rolled east at dawn with fresh dispatches; fish trains rolled west with fresh porgies, crabs and oysters.

The turn of the 20th century saw the LIRR”s purchase by the Pennsylvania Railroad, the largest corporation in the world, and arch-rival of Cornelius Vanderbilt’s New York Central. Both railroads were busy reshaping the city with monumental new buildings and approaches, and converting their commuter rail networks from steam to electrical power.

The simultaneous political consolidation of New York was no coincidence; only if unified would its five sprawling boroughs be strong enough to protect their citizens from corporate giants like these, “the organized forces of relentless and absentee capitalism,” as civic leader Andrew Haswell Green and others would argue.

Locomotive and crew, Wading River, circa 1898. The LIRR retired its last steam locomotive in 1955. Ron Ziel Collection, Queens Borough Public Library.

But New York City’s consolidation also split the railroad’s territory into two legally distinct regions, whose interests would so sharply diverge that citizens of Long Island’s two western counties tended to forget they still occupied the same landmass. And just when the East River tunnels and costly electrification of LIRR commuter lines sent its ridership soaring, new competition from trucks and autos was setting the railroad industry on track to collapse.

Soon, the “Master Builder” Robert Moses would amaze the world as he laced Greater New York with steel and asphalt parkways, bridges, tunnels and expressways. Unlike the steam locomotive, the internal combustion engine promised new freedom of movement and freedom of choice, which the auto industry promised would spur limitless economic growth. Its real costs, of course, have only become clearer over time.

Tearing down old New York to build the new one. George Wesley Bellows, Pennsylvania Station Excavation, circa 1907. Brooklyn Museum.