Rapid Transit in the Steam Age: Commuters

The Dawn of Rapid Transit in NYC: The LIRR in the Steam Age

by Elizabeth K. Moore

Commuters

Illustration from Long Island Of Today, 1884, courtesy of New York State Library Manuscripts and Special Collections

GENTLEMEN,--- There is one class of society for which railways may be said to be peculiarly made; a class whose immense daily increase is, perhaps, one effect of the mechanical discoveries which distinguish this age from all others; and that is, the class of men of business, properly so called; that is, of men of business habits, of men of method… the race which governs the mainsprings of industry and enterprise, and upon which all great transactions ultimately depend.… This leads me naturally to advert to the long-talked of Long Island Railroad…

— S. D., Boston, March 20, 1838

American Railroad Journal

“Commuting,” or daily transit on discounted tickets, is an American term that goes back to the steam ferries serving Lower Manhattan from Brooklyn, the nation’s first suburb.

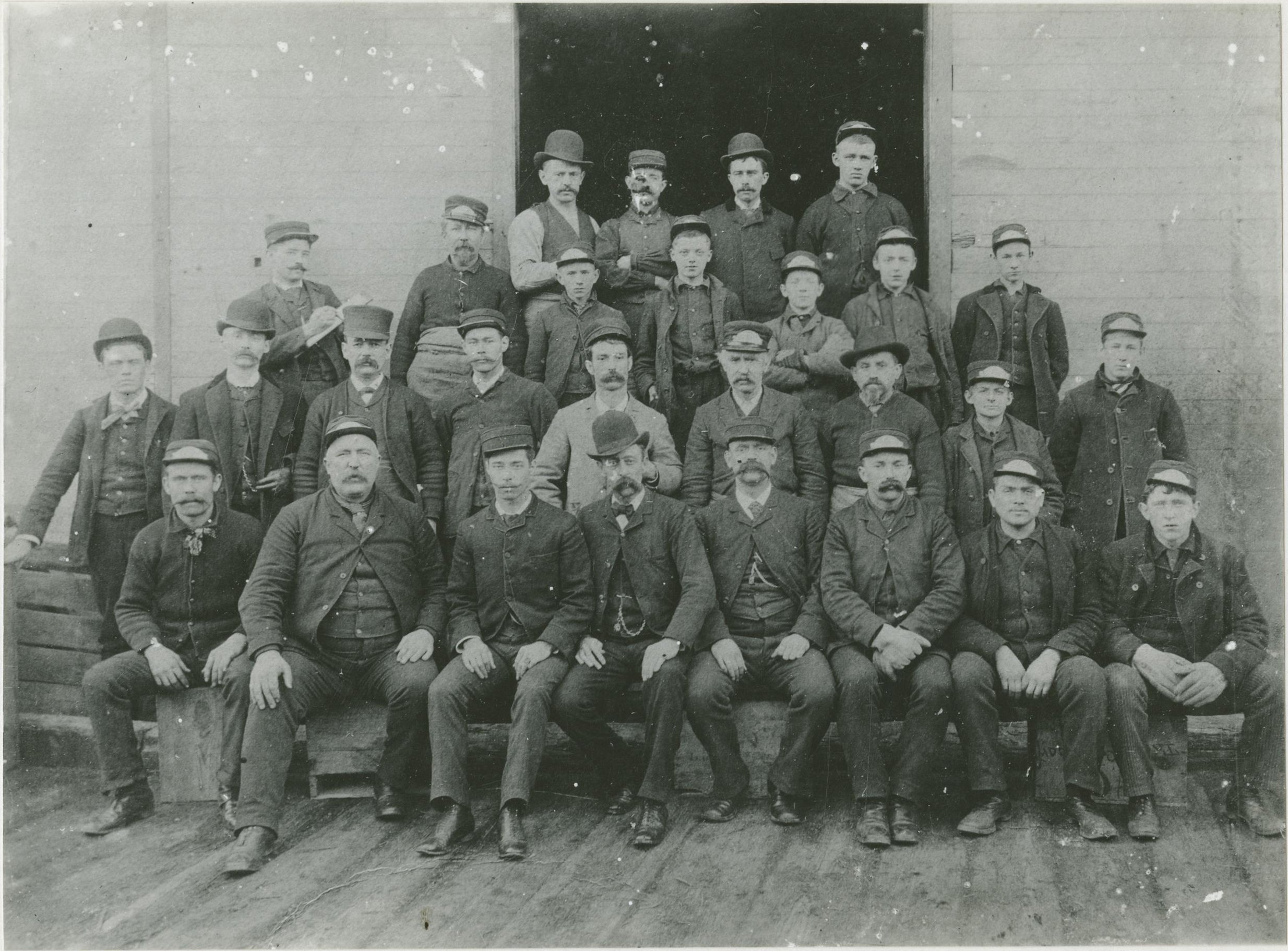

LIRR “Suburban” locomotive and crew, circa 1898. New-York Historical Society.

Twenty years later, steam railroads dramatically expanded the commutation zone, “making it feasible and agreeable for a business-man to be at his counting-house in town during the day, and to reach his summer home before nightfall,” as the LIRR promised.

Where the railroad went, development followed, and the wealthy weren’t the only ones to profit. In 1837, developer John Pitkin invited mechanics, artisans and manufacturers to buy lots along the LIRR line in East New York, where “humble, industrious” men could adapt to the era’s “revolutions in trade” in the “cheapest and safest location,” a mere 25 minutes from New York but free of its taxes.

Long-Island Star, Sept 27, 1827, Brooklyn Public Library. The first "commuter" discounts were advertised as early as 1814 on ferry tickets to Brooklyn.

Advertisement from Colored American, April 11, 1840.

And in 1838, a Black stevedore named James Weeks bought a parcel straddling the tracks in what is now Crown Heights, and with other investors and activists established the community of Weeksville. Its convenient rail service was used to market lots, and Weeksville became a haven and power center for Black New Yorkers. Passenger seating was segregated. But in August 1851, Frederick Douglass’ paper reported, the LIRR provided a special train with 10 cars for a picnic of several thousand people on Black-owned land near Weeksville, celebrating emancipation in British West India — a forerunner of today’s J’Ouvert carnival.

This Feb. 9, 1848 ad in the Sag-Harbor Corrector offered Long Island Railroad "commutation" fares. The Corrector, Feb. 9, 1848.

“We consider commutation to be the life and soul of railways from large cities,” American Railroad Journal & General Advertiser declared in 1846. New Jersey railroads were early adopters of commuter ticket pricing, but Long Island, like the Harlem line, was slower to pick it up, at first focused on building its express service to Boston.

The Central Railroad of New Jersey promoted commuter pricing both as a business tactic and a form of social engineering, which would redistribute the urban population to wholesome environs while building up the railroad — and enriching developers. Its vice president, Dr. R.H. Gilbert, was a former director of field hospitals in the Civil War, and chief engineer and promoter of the first elevated railroad operated in New York. Rail freight was where the money was; commuter service was a loss leader.

By offering monthly tickets at a discount, Gilbert explained, railroads could encourage city dwellers to move their households to serene new homes in the countryside. Those commuters would attract other commuters. The railroad would deliver lumber to build their new homes, and coal to heat them, as well as home goods, groceries, ice, newspapers and mail. Wives and children would pay full price to ride the railroad into the city for entertainment and shopping, and would send their purchases home using the railroad’s horse-drawn express delivery service.

Men relaxing against a fence by the LIRR Main Line near Mineola, 1899. Photo by Hal B. Fullerton, Queens Borough Public Library.

That was the model that was rapidly building the early railroad suburbs of America, such as Llewelyn Park in West Orange, NJ., Riverside, Ill, and Bronxville, NY. By 1852, the Hudson, Harlem and New Haven lines were channeling 2.5 million passengers a year into the city. The LIRR’s traffic was not so heavy: fewer than 200,000 riders were counted in 1845; but more than four times as many by 1869.

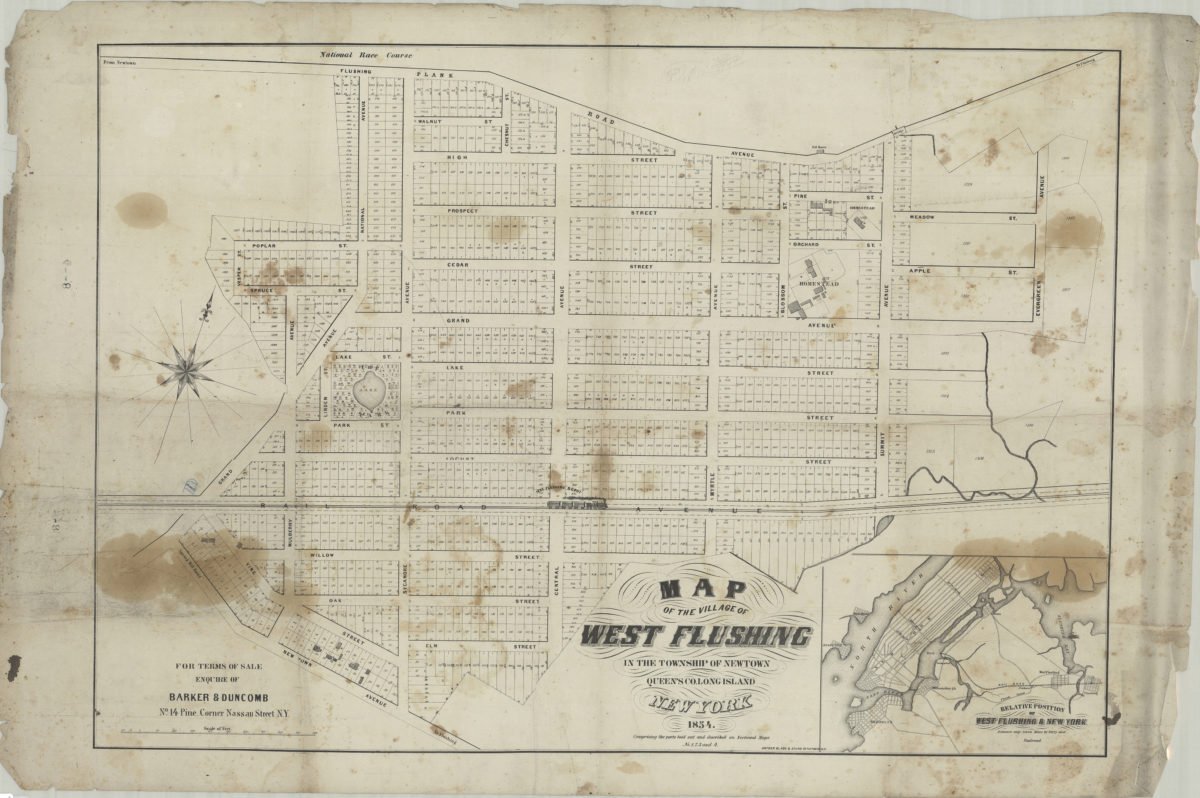

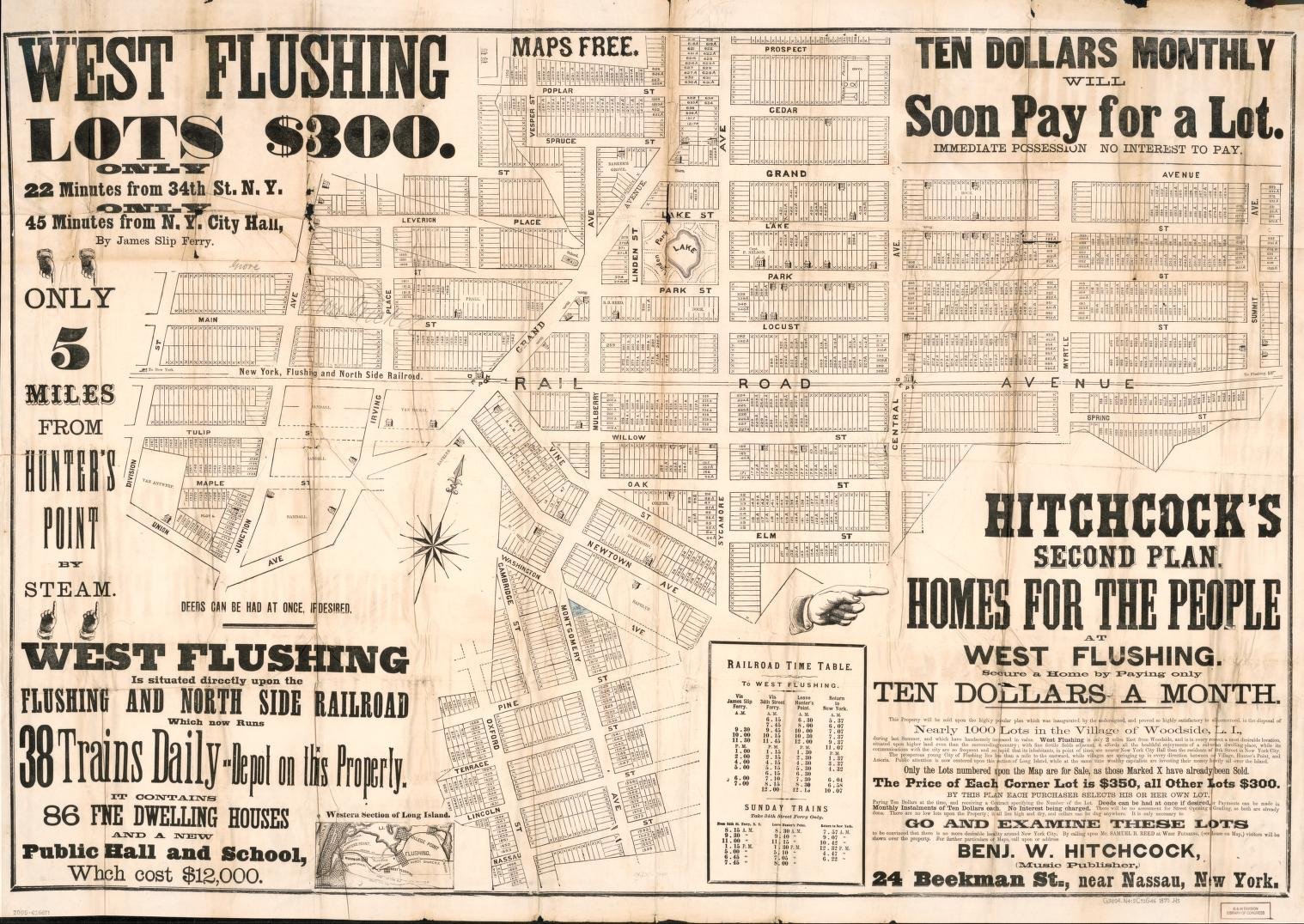

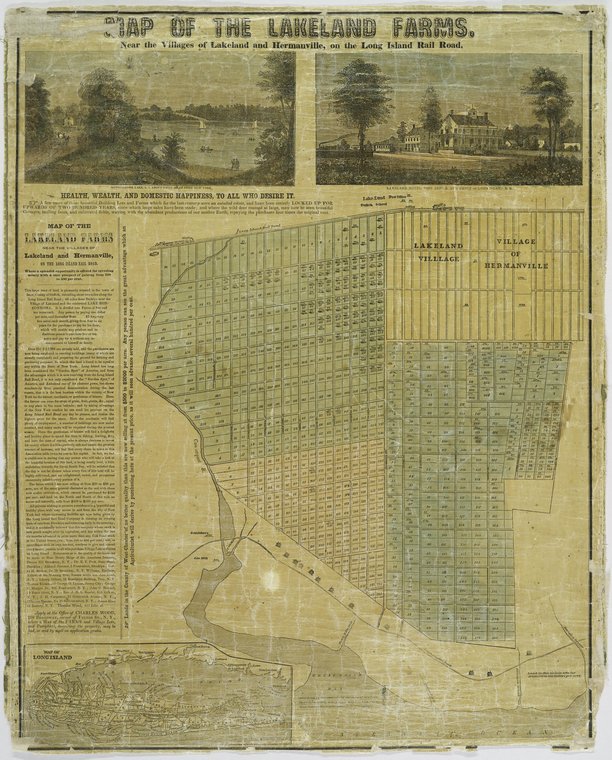

In Queens, a short railroad line linking Flushing with the East River triggered the building of the new community of West Flushing, now Corona. East of Jamaica, “Woodville” was marketed in what is now Woodhaven. Much farther east, the railroad experimented with schemes to encourage development of the cheap real estate along the tracks in what they called the Wild Lands at the island’s empty center.

![Detail from 1852 map by Martin G. Johnson, Woodville Centre property situated in the Town of Jamaica[,] County of Queens, State of New York on both sides of the Long Island Railroad & Plank Roads. New-York Historical Society.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d23a00f53f6300001f811bb/1704397657918-IGUNSRIU6AUJULD9Y84M/10a%2BWoodville%2B1852%2Binset%2B.jpg)

Detail from cartoon, "Humors and Ill Humors of Suburban Travel." Harper’s Bazar, March 19, 1881.

Like other railroads, the Long Island granted free passes to special classes of commuters, such as clergymen and the families of its executives. Prudence dictated granting requests from newspaper editors, too. One such was Evening Post editor William Cullen Bryant, who commuted from his Roslyn cottage to New York from the Mineola station on a free LIRR pass.

The tranquility of the new suburbs was not always matched by the experience of reaching them.

“That railroad is about as poor an affair as bad tracks, slow engines, and frequent stoppages can make it,” the Manhattan diarist George Templeton Strong groused in 1839 after riding the LIRR from Brooklyn to Hicksville. Three years later, he dismissed it as “a miserable affair.”

Initially, commutation tickets were only issued for a year, or portions of a year. By the turn of the century, the Long Island Railroad Company would be selling monthly commutation tickets, good for two rides a day. Businessmen who commuted from homes in Long Island also could buy “family” tickets, good for 500 or 1,000 miles of travel, to be used by their wives, children and household servants.

By the 1880s, LIRR was known for its discomforts. Harper's Bazar, March 19, 1881.

The early railroads experimented with ticket prices and car designs that could pay the bills while yielding to implacable social boundaries of race, class and gender. The first railroad cars were divided into compartments, English style. “Respectable” travelers found it distressing to be forced to mix with people of lesser station in railroad cars, or as George Templeton Strong put it, the “riffraff and ragamuffins of every color and degree” he encountered on the deck of a cross-Sound ferry, when steamboat operator Cornelius Vanderbilt cut prices in a fare war.

For women, railroad travel posed particular challenges. In 1835, Samuel Breck, a wealthy Philadelphian, huffed his disgust in his diary after declining to give up his seat on a New England train for a group of young female mill workers on a day’s outing:

“The rich and the poor, the educated and the ignorant, the polite and the vulgar, all herd together in this modern improvement in traveling… Steam, so useful in many respects, interferes with the comfort of traveling, destroys every salutary distinction in society, and overturns with its whirligig power the once rational, gentlemanly and safe mode of getting along on a journey… Talk of ladies on board a steamboat or in a railroad car! There are none. I never feel like a gentleman there, and I cannot perceive a semblance of gentility in any one who makes part of the traveling mob… To restore herself to her caste, let a lady move in select company at five miles an hour, and take her meals in comfort at a good inn, where she may dine decently.”

A younger observer, Walt Whitman, alluded to that anxiety in 1846, writing about the social changes ushered in by the Long Island Railroad.

“There are divers old fashioned folks, ancient ladies and those under their charge, who cannot get out of their minds a dim connection between the steam-engine and Sathanus — who eschew modern innovations and wish to be taken in Christian style, by the aid of horses’ legs, to the very door of their destination,” he reflected in a Brooklyn Daily Eagle column.

The design of steam engines makes locomotives very slow to accelerate from a standing start. As urbanist Lewis Mumford pointed out, this characteristic made it impractical to place stations closer than a mile apart, giving early American suburbs everywhere their spatial coherence. But it also made steam railroads a bad fit for a rapidly densifying city.

New York rejected steam locomotives from its urban core, and Brooklyn sharply restricted them from the beginning. The population objected to the soot, ash, noise, disrupted traffic, and especially their lethal tendency to startle urban horses. But the railroad’s value to industry and commuters would keep this question controversial in Brooklyn for sixty years.