100 Years Ago: When A Socialist Nearly Became Mayor of NYC

By Aaron Welt

Along with orator Eugene Debs and Congressman Victor L. Berger, Hillquit was one of the most recognized public faces of America's Socialist Party.

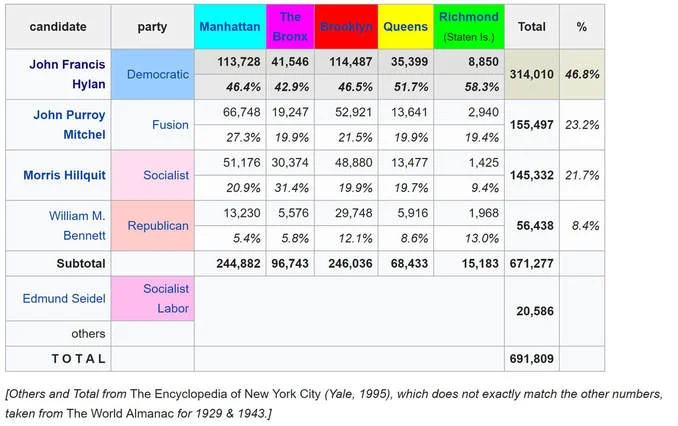

One hundred years ago, a Jewish, immigrant Socialist almost became New York's mayor. For months, detractors watched in horror as the candidate, Morris Hillquit, galvanized much of the city. In April of that tumultuous year, President Woodrow Wilson had reversed course, and bucked popular opinion, asking Congress for permission to send U.S. troops to fight in the "Great War." Hillquit’s campaign galvanized antiwar sentiment in New York. It was also a flash-point for ethno-religious politics in the city. Jewish New Yorkers, in particular, sparred over what Hillquit’s improbable run meant for America’s increasingly immigrant Jewish population. The Socialist lost the election, accruing about half as many votes as the winner, Tammany Democrat John Hylan. But his campaign was a turning point for many communities in New York, and continues to leave its mark on the city.[1]

Hillquit’s mayoral bid was a climax in the history of Yiddish Socialism, a movement he did much to create. Born as Moses Hilkovitz in the Russian Empire, Hillquit immigrated to the U.S. amid the Diaspora of Central and Eastern European Jews. Like thousands of his fellow poor and Jewish migrants, he gravitated to the world of labor unions, the radical Yiddish press, and the Socialist Party. As a young lawyer, he represented the United Hebrew Trades and the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) in their efforts to organize the needle trades. When the mayor, John Purroy Mitchel – his electoral opponent in 1917 – attempted to prosecute ILGWU members for the murder of a strikebreaker, Hillquit served as defense attorney for the union officials. (A jury found all of the accused innocent.) In 1914, Socialist Meyer London won a seat in Congress representing the heavily Jewish immigrant East Side of Manhattan. While other Jewish immigrant radicals won citywide office, Hillquit ascended the ranks of the Socialist Party organization, which rested on the prestige garnered by running Eugene Debs as its perennial Presidential candidate. Very reasonably, Hillquit in 1917 believed that the Socialist Party’s standing with New York’s immigrant working-class could deliver the mayor’s office.

President Wilson’s decision in April to commit American troops to the Entente war effort dominated the 1917 race. Incumbent John P. Mitchel, a moderate, liberal-Progressive reformer running as an independent Democrat, championed U.S. involvement. Mitchel, in fact, volunteered for the war effort, dying shortly after election in military training as a fighter pilot.

Hillquit adamantly opposed American entry. He saw the Great War as a catastrophic failure of European industrialists and aristocrats to contain nationalism. The rural peasantry and urban workers, he and other Socialists argued, stood to gain nothing from the war even while they died by the thousands. For years, Hillquit lobbied against “preparedness” campaigns, or military training initiatives directed towards civilians. In the years following American entry, pro-war zeal prevailed. The Bolshevik overthrow of the Russian Provisional Government that October did much to split the Jewish immigrant left. But the Espionage and Sedition Acts, wartime nativism and militarism, and the postwar Red Scare all stifled Yiddish Socialist politics in America.[2]

"The New Western Front", a Sunday New York Times cartoon of November 4th, 1917, implying that German enemy rulers favored Hillquit and Hylan. The caption reads, Crown Prince: "Any more victories, Papa?" - Kaiser (Wilhelm II): "I can't tell until Tuesday."

The elite of New York City’s Jews denounced Hillquit. So-called “Uptown Jews,” the business and political leaders whose charities aimed to assimilate Jewish immigrants, viewed the Socialist campaign as a major step backward. The former President and ardent war supporter Theodore Roosevelt accused the Socialist of being “an agent of the Prussianized autocracy” and “a Hun inside our gates.” Subsequently, many Uptown Jews worried how Hillquit’s insurgency would affect America’s tolerance of an increasingly urban and immigrant Jewish presence in the US. Attorney, businessman, and Democratic Party functionary Samuel Untermeyer publicly warned that a Hillquit victory “will arouse a storm of hate, resentment, and anti-Semitism such as our race has never before encountered in this country.” With WWI mobilization in full force, the prospect of an avowedly anti-War Jewish immigrant as mayor of the nation’s largest city deeply troubled the uptown faction.[3]

The Socialist projected himself as the candidate of true American values. In his speeches, Hillquit wrapped himself in the American Constitution. To him, President Wilson and Mayor Mitchel’s wartime policies of censorship and surveillance had brought “a sad hour for American liberties, a sad hour for the future of our republic.” At one rally, in a display of boldly patriotic, anti-War political imagery, two fully uniformed Army Privates carried Hillquit out on stage atop their shoulders.[4]

Hillquit’s campaign also appealed to a sector of New York’s growing black population. Thousands of black Southerners fleeing Jim Crow persecution arrived in New York and its war-fueled job market during this period. One of these migrants, A. Philip Randolph, served as Hillquit’s campaign manager in Harlem. That November, the future black civil and labor rights icon managed to pull a quarter of Harlem’s vote for Hillquit. When Theodore Roosevelt stumped for Mitchel in the neighborhood, black Socialists heckled the aged but sturdy war advocate. In the decade after the Hillquit’s campaign, the historically African-American enclave gave rise to a Harlem Renaissance of black, and very often leftist, politics and culture.[5]

But the war question divided Socialists, sometimes in the most intimate ways. For instance, the Socialist husband and wife John G. Phelps Stokes and Rose Pastor Stokes. John Stokes, a native born and Protestant tycoon sympathetic to Socialism, supported American entry into the War. Over 1917, he renounced Hillquit, left the Socialist Party, and supported Mayor Mitchel. Rose Pastor Stokes came from a Yiddish-speaking, immigrant family and after toiling for years as a factory hand became a labor journalist. When Rose Pastor interviewed the left-leaning businessman John Stokes, the two fell in love and later married, eventually becoming the New York press’s favorite radical family. But unlike her husband, Rose believed “the greatest menace to American unity today” in 1917 was the “profit patriot,” the munitions profiteers who animated war hysteria. For Rose, Hillquit offered the best hope to ending the Great War. Other families faced a similar divide as did John and Rose.

Just before Election Day, Rabbi Samuel Shulman of the prestigious Beth-El Temple in midtown Manhattan stepped into the fray. Rabbi Shulman urged Jews to disregard warnings of an anti-Jewish backlash and to vote their conscience. He chastised voices in the community that attempted to set the appropriate boundaries for the Jewish electorate. “This to my mind,” the Rabbi excoriated, “is the extreme of political audacity.” In a swipe at Untermeyer, Rabbi Shulman fumed, “I consider such action as nothing less than a crime against Jews and Judaism.” Though Rabbi Shulman too denounced Hillquit, he maintained that “there is no such thing as a Jewish vote” and to “encourage and spread the dangerous myth that there is such a thing as a Jewish vote en bloc is certainly one of the most unpatriotic acts and a slander of severest sort.” As other Progressive Era commentators observed, and as the 1917 election proved, Jewish politics in America bent towards disagreement rather than consensus.[6]

With all the votes cast at the end of election night Hillquit came in a respectable third place, just behind incumbent mayor. With Mitchel in the race, the reform vote split in the winner-take-all U.S. model, paving the way for Tammany to regain power. The winner, Judge “Silent” John Hylan, a loyal machine operative, had refused to take any public stances on the major issues of the day, including American entry into WWI. Nevertheless, Tammany mayors continued to govern New York until the tenure of Fiorello La Guardia in the 1930s.

While Hillquit lost, however, his impressive 1917 bid offers important insights for students of American history. Although many leaders, including Jews, tried to dismiss him, Hillquit's race electrified working class, immigrant, and Yiddish-speaking New York. Labor historian Melech Epstein writes of “Hillquit’s stirring campaign” that what began as a humble operation, sparked by the unrest of WWI, “progressed into a buoyant hope, bordering on conviction, that the largest city in America would elect a Socialist mayor.” Indeed, nearly a dozen Socialists won seats to city and state offices. The race marked the high point of Yiddish Socialism in the United States, the moment at which workers and immigrants perhaps most shaped the politics of America’s largest city.[7]

Aaron Welt is a Ph.D. Candidate at New York University, specializing in American Jewish history.

[1] “Hillquit or Hylan is Murphy’s Guess,” New York Times, October 17/1917; “Mayor to Tell Why They Back Hylan,” New York Times, October 30, 1917.

[2] “International Socialism Not Even Sleeping,” New York Times, June 4, 1916.

[3] "Hillquit Protests Roosevelt’s Peril,” New York Times, October 20, 1917; “Morgenthau Joins Fight on Hillquit,” New York Times, November 3, 1917; “Urges the Jews to Oppose Hillquit,” New York Times, November 2, 1917; “Untermeyer Defends His Appeal to Jews,” New York Times, November 6, 1917.

[4] “Hillquit Gives President Only Divided Loyalty,” New York Times, October 3, 1917;“Government Keeps Tabs on Hillquit,” New York Times, November 1, 1917.

[5] Cornelius Bynum, A. Philip Randolph and the Struggle for Civil Rights (Urbana: University of Illinois Press), 68.

[6] “No Judaism in Politics,” New York Times, November 4, 1917; “Jews Not a Factor Dr. Shulman Says,” New York Times, November 8, 1917.

[7] Melech Epstein, Jewish Labor in the U.S.A. (New York: Trade Union Sponsoring Co., 1938), 77-78.