A "Madhouse in all its Naked Ugliness and Horror": An Interview with Stacy Horn

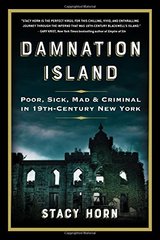

Today on Gotham, associate editor David Thomson speaks with Stacy Horn, author of the new book Damnation Island: Poor, Sick, Mad & Criminal in 19th Century New York, about the dark history of Blackwell's Island, known more commonly today as Roosevelt Island.

First and foremost, what drew you to the topic of the tragic events of Blackwell's Island?

I was drawn in by a lifetime interest in forgotten history, especially if it’s a dark story that involves injustice. In the 19th century, anywhere from 30,000 to 50,000 people were sent to Blackwell’s Island yearly, and what was done to them there is almost completely forgotten. I think we could all guess that it was bad, but what happened specifically, and to whom?

Resurrecting their stories is particularly important in a time when our president is calling for a return to asylums, and the need to close down Rikers Island and enact criminal justice reform has never been more apparent.

For those who are unfamiliar with this history of what is now known as Roosevelt's Island, what types of establishments were built on the island in the 19th century to house the criminal, insane, and deathly ill?

The city started with the best of intentions. Bellevue, which is now known as a hospital, also once housed the city’s Lunatic Asylum, the Almshouse for the poor, the Penitentiary for felons, and the Workhouse, for people convicted of misdemeanors. It was dangerously over-crowded and the conditions were simply criminal. But the city recognized this and they bought Blackwell’s Island with the plan to build replacement establishments that would be state-of-the art, and actual places of reform.

When they built a new Penitentiary, Lunatic Asylum, Almshouse, Workhouse, and various hospitals to care for these populations, they thought they were building facilities that would serve as models for all like institutions to follow.

How did a series of facilities designed in Jacksonian America to be modern and humane become, according to Charles Dickens, "a lounging, listless madhouse in all its naked ugliness and horror"?

There are many reasons, but two stand out above the others. They grossly underestimated the sizes of the populations they expected to maintain and reform, and the cost. No one really knew then how many people were suffering from mental health issues, or the number of homeless, and mass incarceration was a problem that they were about to introduce to the world.

To keep costs down it became almost a mission to see how little they could spend and still keep the inmates alive. Even though they divided everyone into one of two groups — the “worthy poor,” which included widows, children and the old and infirm, and the unworthy poor, which was essentially everyone else — the esteemed worthy poor and the inmates of the Asylum, who were also seen as “innocent,” were treated no better than those who were deemed unworthy.

One of the most unjust outcomes of the arrangement of institutions on Blackwell’s Island was the association it created in the public’s mind, that the poor, criminals, and those judged insane all belonged together in one group. It reinforced a devastating connection, which persists to this day, that people with a diagnosis of mental illness are dangerous, the poor are criminals in disguise, and together with those convicted of crimes they are all somehow “guilty.”

You tell this story through the lives and voices of those who inhabited, worked, and wrote about the island. What drew you to take such an approach to frame the book?

There was no other way to communicate what went on inside those buildings except through the lives of the people forced to inhabit them, and the people who were there to care for them, some of whom were compassionate, many of whom were not. A reader might doubt me, or the inmates, but even prison wardens would decry the conditions. Rev. French, the Episcopal missionary who I feature in the book, testified before the senate that isolating these people away from the public eye, and their friends and family, left them to the tender mercies of nurses and attendants who abused them with impunity. If a patient dared to complain they were never believed and were later punished even more cruelly by the very nurses whose abuse had motivated their complaints.

Could you perhaps tease us with one of your favorite characters from the book that really offers a window into life on Blackwell's Island?

One of my favorite sections is the one I just brought up. There was a couple years of spectacularly lurid events, epitomized by the night when they took a pregnant inmate from the Lunatic Asylum, put her in a straitjacket and threw her into solitary, where she gave birth, alone, and in that straitjacket.

The senate conducted an investigation and Rev. French was subpoenaed. But the night before he was due to testify, French’s superior, Rev. Woodruff, told him he’d be fired if he spoke to the senators. The senators responded by subpoenaing Woodruff. The exchange between the senators and Woodruff is priceless.

The senators couldn’t understand why Woodruff wouldn’t want French to tell the committee of the abuses he’d witnessed, so they could do something about it. Woodruff tried to explain that French was only responsible for the spiritual well being of the inmates, and if he complained too publicly about what really went on the Commissioners who ran the Island would revoke their passes (if you weren’t an inmate or a worker you needed a pass to get onto the island). One senator shot back, “I think it is the opinion of this Committee that if your Society tolerates abuses there and conceals them from the public the quicker you are got off the Island the better it is for those poor unfortunates there.”

The senators should not have represented themselves as so high and mighty. They concluded their investigation without making a single recommendation for change. Nine hundred pages of testimony were produced and nothing improved in the lives of the inmates.

What factors contributed to the demise of the island by the early twentieth century?

Things were actually briefly hopeful at end of the nineteenth century. The problems with how things were run on the island were acknowledged and steps were taken.

The care of people diagnosed with mental health disorders was transferred from the city to the state, and the state did a much better job. At first. But horror stories returned later in the twentieth century, and the trend of deinstitutionalization and the emergence of psychotropic medications has made asylums a thing of the past.

The Penitentiary and Workhouse were likewise deemed hopeless, and the city bought Rikers Island in order to build a replacement Penitentiary and Workhouse. Unfortunately, Rikers is now recognized as one of the worst prisons in the United States and reformers are once again calling for a do-over.

The people in the Almshouse were moved to Staten Island, and the main hospital on the island was relocated to Queens. By the 1950s the island was largely abandoned

How is the story of Blackwell's Island one that translates to the early twenty-first century and that of Rikers Island? Are there indeed any parallels that we can draw on today?

Yes. Building new, state-of-the-art prisons has already been done. To avoid recreating, yet again, the same ugly institutions we already have, certain crucial changes must be made that have nothing to do with the buildings themselves. As reformers have already voiced, we must reform the bail system, reduce the population, and stop isolating the convicted on remote islands. To this I would add we must investigate, arrest and prosecute white collar criminals to the same degree we investigate, arrest and prosecute “blue collar” criminals, and they must be sent to the same prisons instead of being given only fines (if that).

Even wardens in the nineteenth century pointed out how unfair the system was and that only poor people were sent to prison. If Blackwell’s Island, and later Rikers Island, had been populated with as many bankers and business people as other kinds of thieves, the prisons would never have become such nightmarish institutions that demolishing them is the only way to begin again.