Basketball and Black Pride: Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Resident Organizing in New York City Public Housing

By Nick Juravich

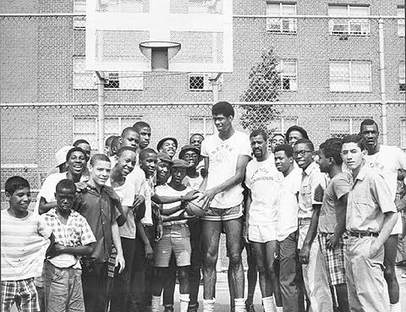

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar (center) and Emmette Bryant (to his right) kick off the summer basketball clinic at the Marcy Houses in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, July 23, 1968. New York City Housing Authority Collection, LaGuardia and Wagner Archives.

In the summer of 1968, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar — known at the time as Lew Alcindor, and just barely twenty-one years old — was already a basketball legend. Impossibly tall and incredibly talented, he had led New York City’s Power Academy to 71 straight wins before joining John Wooden’s UCLA Bruins. After a year on the “freshman team,” he had led the varsity to back-to-back NCAA titles, winning tournament MVP both times (he would add another title and MVP in 1969). And that summer, if you were a kid growing up in one of the New York City Housing Authority’s (NYCHA) developments, you could meet the legend in person.

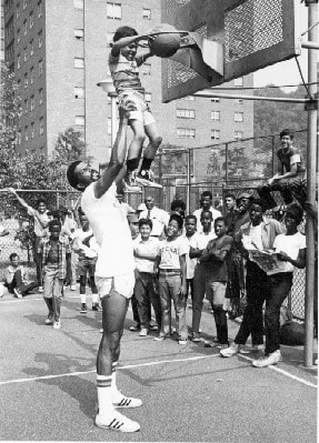

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar could probably have been anywhere he wanted in the summer of 1968. Many people had expected — indeed, had demanded — that he would lead the United States to Olympic glory on the basketball court, but he declined the tryout, boycotting the Mexico City games in solidarity with the Olympic Project for Human Rights. His principled stand sparked a racist backlash, which he could have weathered on a Southern California beach or in the private company of other elite athletes, far from the public eye. Instead, he came home to New York City and led thirty-two basketball clinics for the New York City Housing Authority, in whose buildings he himself had grown up.

We know Kareem Abdul-Jabbar today as a brilliant activist and public intellectual as well as a basketball superstar, a man who was honored with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2015. As historian John Matthew Smith wrote earlier this year, Abdul-Jabbar’s legacy “transcends the game; in the age of Black Power, he redefined the political role of black college athletes.” His work with NYCHA in 1968 — captured in a pair of digitized photos from the Authority’s collection at the LaGuardia and Wagner Archives — offers an early glimpse of his principled commitment to activism as well as athletic achievement. The programs he led also offer a window into the remarkable world of youth programming in NYCHA, which blossomed as a result of resident organizing in the late 1960s and 1970s.

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: The Athlete and Activist in the Age of Black Power

Born in Harlem in 1947, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar moved with his parents to the Dyckman Houses in Inwood in 1950. The move “was really considered a step up,” he told the New York Times in 2009, recalling both the material comforts and the sense of community. He lived there until he left for UCLA.

Though his family had moved north, Abdul-Jabbar was drawn back to Harlem, both to play at the famed Rucker Park “when it was still relatively unknown” and to immerse himself in Black politics and culture. In 1964, he joined a summer journalism program run by Harlem Youth Opportunities Unlimited, Incorporated (HARYOU), the pioneering social work and community empowerment agency founded by Kenneth Clark and headed by Cyril DeGrasse Tyson. The experience proved formative. Abdul-Jabbar’s group was mentored by the historian John Henrik Clarke. They met with Malcolm X, posed interview questions to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and spent hours combing through the collections of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. When the 1964 Harlem Uprising began, the journalism team raced to put out a special issue detailing the causes of the rebellion and the police brutality that sparked it. As Abdul-Jabbar puts it in one of his many books, On the Shoulders of Giants, “I was reborn in Harlem in the summer of ‘64.”

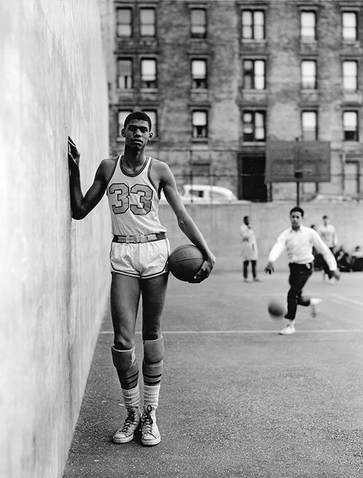

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar at 16, photographed by Richard Avedon, 1963.

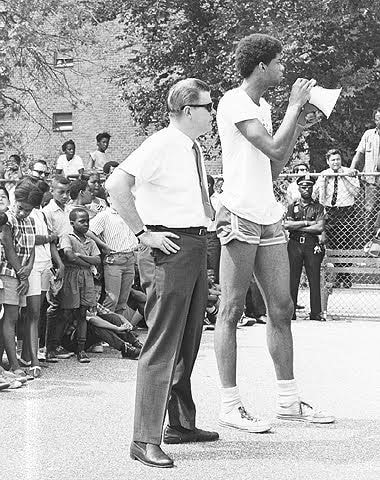

In his most recent book, Coach Wooden and Me, Abdul-Jabbar writes: “my development as a basketball player paralleled my evolution as a social activist.” At UCLA, he dominated college basketball (so much so that the NCAA changed the rules in a failed attempt to limit his impact), and expanded his activism, joining vigils to commemorate the assassination of Malcolm X and presenting to his sociology class on “The Myth of America as a Melting Pot.”[1] He also started giving back. In the summer of 1967, he led his first round of basketball workshops for NYCHA. As he writes in Becoming Kareem, a memoir for young readers, “I was excited to teach them basketball skills, but I was just as excited to instill in them a sense of black pride.”[2]

NYCHA Basketball Clinic, Butler Houses, South Bronx, 1967. New York City Housing Authority Collection, LaGuardia and Wagner Archives.

That same summer, Abdul-Jabbar took part in the Cleveland Summit, in which a group of black athletes convened by Jim Brown made a public statement of support for Muhammad Ali and his decision not to register for the draft. Ali’s fearlessness and conviction proved inspiring. That fall, when Harry Edwards organized the Western Black Youth Conference to promote the Olympic Project for Human Rights, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar made his voice heard. As historian Louis Moore writes in We Will Win the Day, Abdul-Jabbar provided “the most memorable and most effective words” at the event.[3] He shared a story of nearly being killed when a racist cop fired into a crowd in Harlem, and explained, “I found out last summer that we don’t catch hell because we aren’t basketball stars or because we don’t have money. We catch hell because we are black” (John Matthew Smith notes the direct echo of Malcolm X in Abdul-Jabbar’s choice of phrasing).[4] As for the boycott, Abdul-Jabbar was for it. “Somewhere, each of us has got to make a stand against this kind of thing. This is how I take my stand — using what I have. And I take my stand here.”[5] Harry Edwards later called Abdul-Jabbar’s words “the most moving and dynamic statements on behalf of the boycott.”[6]

While the broader boycott never materialized, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar stuck to his convictions, despite facing what he later described as “a firestorm of criticism, racism, and death threats.” Ultimately, he “couldn’t shake the feeling that if I did go and we won, I’d be bringing honor to the country that was denying our rights.” He tried to explain to hostile reporters that “true patriotism is about acknowledging problems and, rather than running away from them, joining together to fix them,” but he was met with racist epithets and suggestions that he leave the USA.[7] None of this, however, stopped him from walking the walk, and he headed back to New York City to instill black pride in another generation of young people from public housing.

His message was an urgent one. In the very NYCHA development where these photographs were taken, the Marcy Houses, 17-year-old resident Edward Troutman was killed by a police officer who fired into a crowd just a month before Abdul-Jabbar arrived to lead his clinic. The notes accompanying these photos contain no records of conversations between Abdul-Jabbar and the young people who witnessed this deadly police violence. If these conversations did take place, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar was clearly equipped to respond with empathy and resolve.[8]

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar kicks off the summer basketball clinic at the Marcy Houses in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, July 23, 1968. New York City Housing Authority Collection, LaGuardia and Wagner Archives.

Resident Organizing and Youth Programs in Public Housing

The summer of 1968 marked a new direction for the New York City Housing Authority, as well. Both the Authority and its residents were struggling to make ends meet. After decades of federally-backed construction, funding for daily maintenance and operations in public housing was proving difficult to procure from Washington. Practices of metropolitan segregation ensured that NYCHA increasingly housed Black and Latinx New Yorkers who were denied access to homeownership, credit, or stable jobs in the city’s deindustrializing economy. With fewer resources to deliver on its promises, the Authority’s traditional, paternalistic model of governance no longer worked. The killing of Edward Troutman by one of the Housing Authority’s own police officers showed just how deadly administrative racism could be if left unchecked.

Basketball at the Red Hook Houses, June 19, 1940. New York City Housing Authority Collection, LaGuardia and Wagner Archives.

At the same time, however, the Black freedom struggle and the War on Poverty — with its promise of “maximum feasible participation” for poor people in the bureaucracies that governed their lives — had galvanized a new generation of tenant activists. As this author argued in an article for the Journal of Urban History last year, this upsurge of tenant organizing led NYCHA administrators to (haltingly) embrace tenant-run programs, particularly those for young people. The first of these were NYCHA’s Tenant Patrols — resident-run public safety and maintenance services, formally inaugurated in 1968 — which not only employed teenage residents, but distributed thousands of free summer lunches to children of all ages by the 1970s. The Resident Advisory Council, formed in 1970, served as a clearinghouse for a wide variety of tenant organizing, from voter registration drives to drug treatment programs, but fully half of the Council’s programming — which served 100,000 tenants by 1975 — was targeted to young people.[9]

Basketball featured prominently in this world of tenant programs for young people. NYCHA’s developments formed teams and competed in a citywide championship for both men and women. Winning was no small feat, as NYCHA housed nearly half a million people. Local resident councils also organized their own recreational programs. Geraldine Lamb, who later became the citywide Resident Advisory Council president, ran a “midnight basketball” program in the Castle Hill Houses for years, which not only offered kids a place to play while their parents worked night shifts, but also provided meals, tutoring, and camaraderie.[10]

Basketball Clinic at the Queensbridge Houses, July 28, 1970. New York City Housing Authority Collection, LaGuardia and Wagner Archives.

Tenant-run programs provided recreation, education, and empowerment to young people growing up in and around NYCHA developments. Beyond basketball, the Resident Advisory Council sponsored a “NYCHA Olympics” in track and field, a city-wide talent competition with celebrity judges, and a “NYCHA Orchestra” that provided free outdoor concerts for residents. Combined with more overtly political organizing, these efforts offered joy and opportunity to a generation of New Yorkers, and they are a major reason that public housing still stands in New York City. As historian Fritz Umbach writes, “The survival of New York’s public housing system... is arguably one of the more enduring legacies of black and Latino activism in New York City.”[11]

NYCHA Basketball Championships for Women and Men, February 24, 1973. New York City Housing Authority Collection, LaGuardia and Wagner Archives.

A Legacy of Athletic Activism

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s basketball clinics for young people in NYCHA should be understood both as part of his own remarkable life of activism and as part of a wider world of NYCHA resident organizing, in which he had grown up, and to which he gave back. Much as Colin Kaepernick has done today with his “Know Your Rights” initiatives while blacklisted by the NFL, Abdul-Jabbar used these clinics to merge athletics and activism and to inspire and educate young people.

Look again at the photo of twenty-one-year-old Lew Alcindor at the Marcy Houses in Brooklyn in 1968. The faces of the young people around him speak volumes; the boy holding the basketball with the greatest college player on the planet can barely believe it. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar could have been many places in the summer of 1968: winning a gold medal, relaxing on a beach, hobnobbing with the Los Angeles elite. Instead, he took a principled stand against American racism, and then came home to teach young people how to do the same, on and off the court.

Nick Juravich is the Andrew Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow in Women's History at New-York Historical Society and Associate Editor of Gotham.

Notes

[1] John Matthew Smith, “‘It’s Not Really My Country’: Lew Alcindor and the Revolt of the Black Athlete” Journal of Sport History, Summer 2009, 231-32.

[2] Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Raymond Obstfeld, Becoming Kareem: Growing Up On and Off the Court (New York: Little, Brown, and Company, 2017), 236.

[3] Louis Moore, We Will Win the Day: The Civil Rights Movement, the Black Athlete, and the Quest for Equality (New York: Praeger, 2017), 174.

[4] Smith, “‘It’s Not Really My Country’,” 223.

[5] Moore, We Will Win the Day, 174.

[6] Harry Edwards, The Revolt of the Black Athlete (New York: The Free Press, 1969), 53.

[7] Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Coach Wooden and Me: Our 50 Year Friendship, On and Off the Court (New York: Grand Central Publishing, 2017). Excerpted for NBC Sports.

[8] Fritz Umbach, The Last Neighborhood Cops: The Rise and Fall of Community Policing in New York Public Housing (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2011), 67-69.

[9] “The NYCHA Tenant Programs Come of Age,” New York City Housing Authority Collection, LaGuardia and Wagner Archives, Box 90B3, Folder 7.

[10] Geraldine Lamb, Interview with the Author, May 30, 2014.

[11] Umbach, The Last Neighborhood Cops, 6.