Beating Wings in Rebellion: The Ladies Literary Society Finds Equality

By Jerry Mikorenda

In the early decades of the 19th century, no group was more denigrated or rendered more powerless than African American women. In 1834, Henrietta R. Ray, Abigail Mathews, Sarah Elston and several others decided to do something about it. If society wouldn’t assist them, the women would help themselves. They formed the Ladies Literary Society of New York City in Ray’s words to aid in, “acquiring literary and scientific knowledge.”

They were not alone. Between 1827 and 1841, African American women in Manhattan formed at least 17 associations. Among them were the African Dorcas Association, the Female Mite Society and the Female Branch of Zion. Modeled after the societies black men formed, the female groups were expected to toil in the background and defer to the male perspective in all matters of import.

It didn’t quite work out that way.

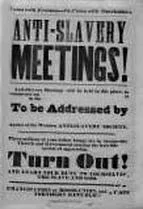

Literary societies were safe havens for African American women to learn to read, write and discuss ideas of the day. Members raised funds for antislavery causes, participated in boycotts, held clothing drives, sponsored lectures and lending libraries while collecting petitions against slavery. These petitions were so successful in 1836 Congress passed a “gag rule” to stop them. In 1838, the Ladies Literary Society raised funds used to help among others a Maryland slave to escape to freedom. The world would later know him as Frederick Douglass.

Black activist Maria Stewart joined the upstart Manhattan society after Boston shunned her. Chastised as a radical troublemaker, Stewart orated at “promiscuous meetings” where men and women sat next to one another. She became the first African American female to make a formal public speech.

During these speeches, she shook her fist shouting, “How long shall the fair daughters of Africa be compelled to bury their minds and their talents beneath a load of iron pots and kettles?” Black and white male abolitionists took umbrage with Stewart for daring to challenge male authority. She also condemned white women for not standing with their black sisters against slavery.

Some white female abolitionist groups began heeding Stewart’s words and invited black women to join their meetings. Listening to the abuses African American women suffered heightened the awareness of the inequality every woman in America faced. The idea of putting sisterhood above race came to a head in 1837 as Manhattan’s white female abolitionists prepared to host the first antislavery convention for women. Anticipating invitations, the Ladies Literary Society was shocked to learn that black women were banned in their hometown from attending the four-day proceeding.

Renowned white abolitionists Angelina Grimké, Mary Weston Chapman and Abigail Kelly took up the cause of their black New York sisters with blistering attacks. Abigail Cox, leader of Manhattan’s white Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society, was described as living in, “a very sinful state of wicked prejudice” while Grimké said the white Society was, “utterly inefficient” and “paralyzed by sinful prejudice.”

The controversy threatened to destroy the convention before it started. Faced with public humiliation, the white New Yorkers backed down. The black female voices were heard. On Tuesday, May 9, 1837, a contingent of six women from the Female Literary Society joined the convention along with 200 other black and white women from around the country.

The threat of violence from onlookers during such meetings was always present. For protection, and to show equality, white female delegates often walked arm in arm into convention halls with their black sisters. The New York City convention now represented all of its members. As Angelina Grimké proclaimed in her remarks, “…the more we mingle with our oppressed brethren and sisters, the more deeply are we convinced of the sinfulness of that anti-Christian prejudice which is crushing them to the earth.”

Although hosting the convention, the white New York females were out of step with the times. Desperately trying to cling to the past, they voted against every resolution that promoted racial or gender equality. Enlightened white females grew to see the bigotry their black sisters confronted as similar to the sexism they faced every day. The female abolitionists began to widen their perspective. Ending slavery was still paramount, but the rights of all Americans needed recognition as well.

A meeting between female abolitionists at the World Anti-Slavery Convention in 1840 brought these two movements together when Lucretia Mott met young Elizabeth Cady Stanton. By 1848, the first women's rights convention ratified a Declaration of Sentiments at Seneca Falls, NY.

Years later, Charlotte Woodward, who was the only original suffragist to live long enough to vote in 1920 (she didn’t because of illness), recounted those early days. “I do not believe there was any community anywhere in which the souls of some women were not beating their wings in rebellion.” Twelve resolutions dealing with women’s rights passed that day. The participants, male and female, agreed the right to vote should be universal for all.

The good feelings from Seneca Falls wouldn’t last. After the Civil War, the push to ratify the 14th and 15th Amendments to the US Constitution guaranteeing all black males’ citizenship and the right vote, led to a split in the movement. The suffragettes wanted to ensure the inclusion of women’s rights in any voting bill while Radical Republican reformers backed citizenship rights for black men as a more expedient goal.

In 1866, Susan B. Anthony threw down the gauntlet saying, “I will cut off this right arm of mine before I will ever work or demand the ballot for the Negro and not the woman.” Stanton, who once stood with the early abolitionists, put the rights of white upper class females above all. When asked if African American males should have voting rights, she said, “What will we and our daughters suffer if these degraded black men are allowed to have the rights that would make them even worse than our Saxon fathers?”

In the latter part of the 19th century, more often than not, the suffragette movement broke along color lines. African American woman led by Helen Cook, Mary Church Terrell and Ida B. Wells formed organizations such as the Northeastern Federation of Colored Women's Clubs and the Colored Women's League to promote black female suffrage. These groups banded together to support their communities much the way their great grandmothers did in the 1830s.

By 1913, when 5,000 women rallied for the right to vote during Woodrow Wilson's inauguration, white members of the National American Woman Suffrage Association refused to march with Wells and their black sisters. Wells waited for the objectors to pass and marched anyway with serval white supporters by her side. One can only imagine that as Wells strode proudly down Pennsylvania Avenue she carried the mantle of the old New York City female literary societies with her.

Jerry Mikorenda is a writer living in Northport. His articles have appeared in The New York Times, Newsday, and The Boston Herald, among other magazines and blogs. He recently completed a biography of Elizabeth Jennings, entitled The First Freedom Rider.

Sources

Alexander, Leslie M., African or American? Black Identity and Political Activism in New York City, 1784-1861 (University of Illinois Press, 2008).

Boylan, Anne M.,The Origins of Women's Activism (UNC Press, 2002).

McHenry, Elizabeth, Forgotten Readers: Recovering the Lost History of African American Literary Societies (Duke University Press, 2002).

Porter, Dorothy B., Activities of the Negro Literary Societies 1828-1846 (1936).

Sterling, Dorothy,We Are Your Sisters: Black Women in the Nineteenth Century (1997).

Yellin, Jean Fagan,The Abolitionist Sisterhood: Women's Political Culture in Antebellum (1994).