Beyond “Ghetto Arts”: Vinnette Carroll’s Urban Arts Corps

By Hillary Miller

Mayor Beame could not be there yesterday morning because of such pressing matters as the city’s new budget, but, if he had he would have observed his Commissioner of Cultural Affairs in a hand-clapping foot-stomping dance with cast members of Don’t Bother Me, I Can’t Cope. —- New York Times, May 16, 1974

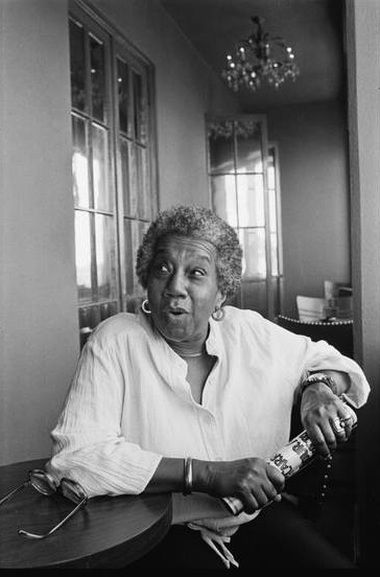

Vinnette Carroll, 1979, Photograph by Marianna Diamos, Los Angeles Times Photographic Archives (Collection 1429). UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA

This unexpected musical routine took place on a platform in front of the Edison Theater on West 47th Street, where Vinnette Carroll and Micki Grant’s hit show, Don’t Bother Me, I Can’t Cope, was enjoying what would become a two-year run on Broadway. The occasion was the announcement of a new program, “Broadway in the Parks,” which brought free performances of Cope to twelve parks and community centers across the five boroughs, including Central Park, Tompkins Park in Bedford-Stuyvesant, the Store Front Museum in South Jamaica, Queens, and the Henry Street Settlement on the Lower East Side. The Pepsi-Cola Company, in cooperation with the Parks, Recreation and Cultural Affairs Administration (PRCAA), sponsored the program. The musical, with lyrics and music by Grant and choreography by George Faison, marked a turning point for Carroll’s troupe, the Urban Arts Corps (UAC). Previous UAC shows toured parks and housing projects, but Cope traveled from a new base: Broadway.

The following is an excerpt from the forthcoming Drop Dead: Performance in Crisis, 1970s New York (October 2016), published courtesy of Northwestern University Press. A book launch and panel discussion of theater in New York City during the 1970s will take place at the Martin E. Segal Theatre Center on Monday, October 31. Full event information here.

Carroll’s Urban Arts Corps developed Don’t Bother Me, I Can’t Cope at her home base, a second-floor “miniature theater” in a former factory at 26 West Twentieth Street, in Chelsea. But the company branched out across the neighborhoods of the city every July and August, with Carroll’s Urban Arts School summer program. City tours became a constitutive element of UAC’s development process -- not just of plays, but of actors, neighborhoods, and neighborhood spaces. By 1975, the troupe had toured Don’t Bother Me I Can’t Cope through outdoor locations across the five boroughs, the Off-Broadway Playhouse Theatre, and the Edison Theatre on Broadway. The music-filled play drew its energy from ritual traditions, Brechtian presentation styles, and the bitter pill of urban life. In “All I Need,” the character Sheila sings alone:

I don’t need your platitudes

I don’t need your pity

I don’t need your Gallup polls or your ad hoc committee

I don’t want your sympathy without respect

I don’t need your study groups or your benign neglect.[1]

Mainstream critics were complimentary but not quite sure what to make of Cope’s mixture of humor and “militancy.” The play eventually found its audience through a lengthy path of revision and remounting, from the streets to Off-Off to Off. By the time it reached Broadway in 1972, Grant’s lyrics succinctly rehearsed local frustrations. Carroll had spent two years conceiving and directing Cope with “the Core” -- her name for her semi-regular collaborators at UAC.

Playbill visual

UAC’s vibrant production history during this period attests to a changing approach from the state-sponsored “Ghetto Arts” programs to the city-supported “cool streets” initiatives of Mayor John Lindsay, culminating in an abandonment of comparable support for the company’s core activities by the late 1970s. Carroll demonstrated the ways in which city, state, and federal programs could collaborate with director-educators to benefit aspiring and underserved performers. Her core of mostly black and Latino actors frequently hailed from the five boroughs. Many young artists arrived at UAC after graduating from New York’s public high schools; others emerged from conservatories, or met Carroll through friends. She auditioned new actors with a simple command: sing something a cappella. (Jennifer Holliday chose “God Will Take Care of You.”) Actor James Earl Jones, one of Carroll’s students, recalled the pragmatism of her pedagogy: “Even though us young ones were in there to learn the craft better to make a better living, we were never deluded to think that we were going to be fed by anybody else but ourselves. That was the reality, especially in those days.”[2] Carroll modeled a performative urban citizenship for young artists who often felt at best ignored and at worst abandoned by the mechanisms of city government.

In her long career, Carroll created elaborate plays with extended production lives, in a world of elite, white, Broadway producers. To do so, Carroll revised the outdated structures of “Ghetto Arts” programs and worked within the shells of governmental initiatives to create theater about the fundamental interdependence of artists, and the residents in the city. Numerous theater companies in the 1970s shared Carroll’s motives, but few enjoyed her outcomes. These companies often had key characteristics in common: their leaders began careers at social service organizations, day care centers, and high schools. They did not focus exclusively on distinct, privileged performance sites, but rather assumed as desirable the participation of audiences across the entire map of the city. They developed networks from city agencies, YMCAs, settlement houses, acting training programs, and schools. Their priorities blended theories of 1960s racial pride and political subjectivity with a drive to educate young artists to withstand the trials of the arts professions. Most crucially, a focus on communicating the nuances of the deteriorating “urban condition” emerged as central to the process of creation: the streets were not merely their stages, but also their incitement.

***

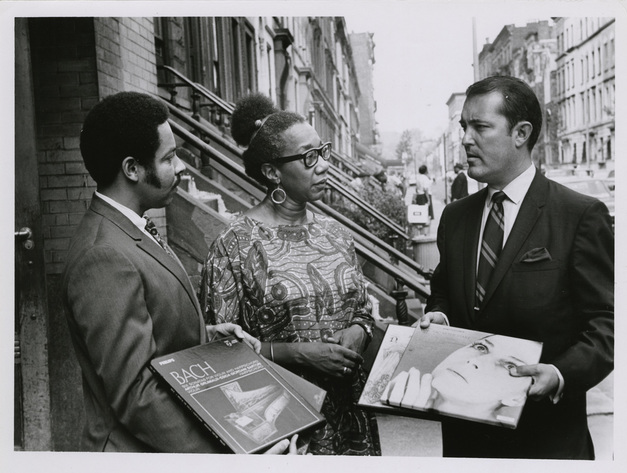

Cyril O. Packwood, librarian & historian; Vinnette Carroll; Don. B. Currant, the American Broadcasting System, date unknown. (Image courtesy Photographs and Prints Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations)

The deprivation imposed by the white community on the Black Artist is not only crippling to the Deprived, but also to the Depriver.

—- Vinnette Carroll, 1969[3]

New York Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller founded the Ghetto Arts Program (GAP) in 1966, and in 1967 John B. Hightower, the executive director of the New York State Council on the Arts (NYSCA), appointed Vinnette Carroll as director. Carroll’s UAC emerged in 1967 as a pilot project of GAP, and its initial members were black and Puerto Rican students aged seventeen through twenty-two, from public schools and youth agencies. Carroll directed a $350,000 budget, and immediately undertook two projects: the UAC and “Summer on Wheels,” the latter of which brought free traveling performances to city residents. This critical development occurred after NYSCA supported Carroll’s study of cultural needs in Harlem and Bedford-Stuyvesant. In response to the cultural privations identified in her study, Carroll established the UAC with two missions: to provide direct collaborative performing arts experiences to culturally underserved urban communities, and to develop a major repertory company that produced new plays. The former was not to be misconstrued as therapy, or social work, but an arts program capable of developing techniques, validity, and artistic relevance. All of this depended upon Carroll and her collaborators to establish professional standards, effective teaching methods, and a focus on process and product, as well as performance.

Carroll viewed GAP as an overdue and yet potentially misguided undertaking. She recognized its problematic and imperialist overtones, and did not want the project “to be an ineffectual community unit because of Eurocentric male autonomy in the governance of the program.”[4] However, she also saw GAP in light of the needs identified in her study; she approached the state apparatus with a muted hopefulness in the face of its potential dangers. Hightower heeded Carroll’s warnings, and they founded GAP on a radical premise: “to find out what the ghetto community wanted rather than what we, as an outside agency, decided it should have.”[5] Carroll was the right person to negotiate these challenges; a trained clinical psychologist, she studied acting with Erwin Piscator at the New School, and with Lee Strasberg and Stella Adler at the Actor’s Studio. While working as an actor in New York, she taught drama at the High School of Performing Arts (1955–66), and briefly worked with the federally subsidized Inner City Repertory Company in Watts, Los Angeles. She had already won an Emmy and multiple awards for her work as a director and actor; she no doubt knew that the implementation of her particular vision for the UAC would make it challenging for the company’s repertory work to garner mainstream attention.

Outdoor performance of the musical Croesus & the Witch, c. 1973

(Image courtesy Photographs and Prints Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations

Carroll eventually sustained a core of twenty-five performers, and the UAC expanded from summer to year-round, working at the forefront of a movement to extend and institutionalize practices initially fashioned as “pilots.” There was evidence that a robust demand for such activities existed, and a growing awareness that low-income areas did not suffer only from low employment and housing shortages. Arts and the People, a 1973 report sponsored by NYSCA and the National Research Center of the Arts, indicated that within the state’s urban areas, a “culturally inclined coalition” was not actively engaged.[6] Among urban residents with a high school education level, blue-collar workers, and those in the low-income brackets, proportionally “non-white,” there was a clear pattern of “cultural frustration.” Regardless of New York’s international reputation as a post-World War II culture capital, those who lived in the city felt even more strongly than upstate dwellers that they did not have access to the arts. The study also revealed that preferences for types of performance differed: 75 percent of the “nonwhites” polled favored seeing amateur actors from the neighborhood or community, and one-third of New York City residents said it was important to have activities that they “could take part in.” All New Yorkers surveyed expressed a desire for culture, yet some felt that it was not within their reach.

One of UAC’s first touring shows of the 1970s was But Never Jam Today, Carroll’s adaptation of Alice in Wonderland with a cast of fourteen actors, and original music by Howard Roberts infused with gospel, calypso, and American folk music. Lindsay’s Urban Action Task Force funded the tour with additional monies donated by the composer Richard Rodgers’s wife, Dorothy, an early supporter of both NYSCA and the UAC. Carroll’s most significant collaboration of the 1970s was with lyricist, composer, writer, and performer Micki Grant. In 1971 Croesus and the Witch, conceived and directed by Carroll and dramatized by Grant, traveled the city’s neighborhoods, touring parks and streets before returning to its West Side location.

Their Don’t Bother Me, I Can’t Cope transferred to Broadway in 1973, where its jazz and funk-inflected songs vented the rage of citizens trapped between contradictions and expectations: “Love, hate Uptown, downtown Separate state. If I sit in I get arrested. If I break in I get arrested. If I shout nobody answers. If I knock I’m Uncle Tom. Questions!” Confused characters—“so many voices preaching”—toggle between conflicting desires for peace marches and militancy, violence and passivity, standing tall and bending. “Fighting for Peace” demanded a break from the fighting, on the street, in the supermarket, across the country, and across the globe; “Good Vibration” bounded back with a jubilant, evangelical joy.

The Grant/Carroll collaboration valorized resilience, both in its lyrics, its staging, and its performance schedule, as it snaked from the streets to the UAC theater, Off Broadway, other cities, Broadway, and right back out into the boroughs. Carroll’s subliminal argument leveled the hierarchy of neighborhood versus professional stages in a desire to deliver its message across the parallel hierarchies of taste. Injustice, power, mystery, ethics; an exuberant score gave voice to a disheartened city, while poking fun at its irrational fears:

Now all the good white folks have gone and left town

For it wasn’t fun any more,

When those fun colored folk left the cocktail party

And bought the house next door.

By the time Cope closed in October 1974, New York City’s unemployment rate surpassed 10 percent, and residents faced widespread layoffs across the public sector. In March 1975 Carroll’s group again performed on a public stage, this time at the New York Hilton, to an audience of 1,000 government officials and business leaders, in a spoof of the city’s fiscal problems. Since 1923 the Inner Circle, an association of city beat reporters, annually performed a song-and-dance show lampooning city politicians. If the mayor accepts the invitation to attend this black tie event, the rules allow for his administration to prepare a rebuttal in the form of a skit. After a city official saw the UAC’s adaptation of a Jamaican folk tale, Carroll’s company secured an invitation to perform Mayor Beame’s rebuttal to “Abie’s Irish Woes.” In the night’s three-act play, the main character, a laid-off zookeeper, lambasted the mayor’s job cutbacks to the tune of Jim Croce’s 1973 pop hit, “Bad, Bad Leroy Brown”:

It transpired, I was fired,

Me and several thousand more

Me and cops and sanitmen [sic]

And firemen were going out that door,

But it’s funny that the money

That they took from our backs

Went right down to the party’s clubhouse

As a raise for all the hacks.[7]

The New York Times declared the performance a successful “marriage of politics and theater with a more polished veneer than the theatrical politics common to City Hall.” But the cutbacks were real, the unemployed city worker a new trope. The politics of retrenchment affected zookeepers and arts groups alike; the UAC and so many others relied on relatively limited amounts of municipal funding for their operations. The City Hall performance did not alter Carroll’s fortunes; just one year after the Inner Circle appearance, Carroll commented on the frustrations of being a Tony-nominated director who was unable to pay the rent on her theater space. When asked her greatest artistic need, she replied: “For more money.”[8] UAC enjoyed the recognition from Cope and its prolific output of plays, but this did not translate into meaningful support for a company that needed funds for space, operations, and for its training component and repertory.

Hillary Miller is Assistant Professor of Theatre at California State University, Northridge. This post is an excerpt from her new book, Drop Dead: Performance in Crisis, 1970s New York, published courtesy of Northwestern University Press (c) 2016, Performance Works (Series Editors: Patrick Anderson and Nicholas Ridout), http://nupress.northwestern.edu.

Notes

[1] Micki Grant and Vinnette Justine Carroll, Don’t Bother Me, I Can’t Cope (Electronic Edition, Alexander Street, 1970, 2014), 34. Also published in Don’t Bother Me, I Can’t Cope: A Musical Entertainment (New York: Samuel French, 1972).

[2] James Earl Jones, quoted in “Profile: Life of Vinnette Carroll, Who Died This Week,” Washington, D.C., National Public Radio, 2002, http://search.proquest.com/docview/190126731?accountid=14026.

[3] Vinnette Carroll, “To Journey to Each Other,” New York Times, February 2, 1969, D9.

[4] Vinnette Carroll, quoted in Calvin A. McClinton, The Work of Vinnette Carroll: An African American Theatre Artist (Lewiston, N.Y.: Edwin Mellen, 2000), 94.

[5] Junius Eddy, “Government, the Arts, and Ghetto Youth,” Public Administration Review 30 (July/August 1970): 402. This was essential given the makeup of the State Arts Council, which had been criticized as a homogenous body representing primarily middle- and upper-middle-class white values.

[6] Arts and the People: A Survey of Arts and Culture in New York State (New York: American Council for the Arts in Education, 1973), 91. Similar studies included a NYSCA-funded survey by Tom Lloyd’s group, the Community Artists Cultural Survey Committee, backed by Thomas Hoving at the Metropolitan Museum, as well as a survey conducted through the American Association of Museums and funded by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. See “Museums and the Ghetto,” Newsweek, vol. 76, August 17, 1970, 93.

[7] “Carey and Beame Are Satirized Here by the Inner Circle,” New York Times, March 2, 1975, 40.

[8] Clifford Mason, “Vinnette Carroll Is Still in There Swinging,” New York Times, December 19, 1976, X4-X5.