Bob Dylan’s New York, 1961

By Stephen Petrus

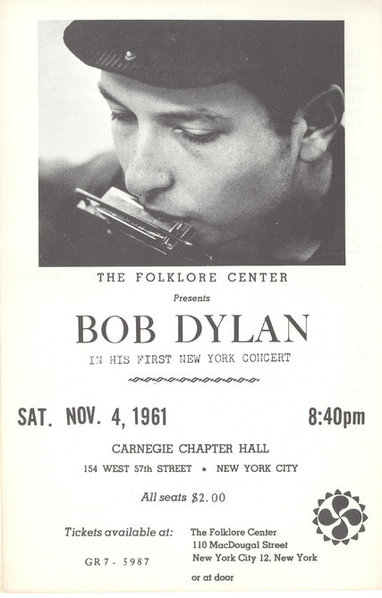

Flier for Bob Dylan's first official solo concert, on November 4, 1961, at Carnegie Chapter Hall. Organized by the Folklore Center's Izzy Young, the event was attended by only 53 and went largely unnoticed. Courtesy Ronald D. Cohen.

The following is an excerpt from the author’s book, Folk City: New York and the American Folk Music Revival, courtesy of Oxford University Press.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Greenwich Village was a conduit of ideas, made possible by the concentration of performance spaces around Washington Square Park. If observers wondered why the folk music revival flowered in the Village, they needed only to walk down MacDougal Street from West 4th and make a left onto Bleecker. Numerous clubs lined these colorful streets. The density fostered creative interactions as well as collaboration and competition, and the Village became an engine of artistic innovation. Skilled and striving artists in close proximity challenged traditional boundaries in folk music, both in lyrics and in style. Jazz composer, multi-instrumentalist, and folk singer David Amram observed, “There was a cross-pollination of music, painting, writing—an incredible world of painters, sculptors, musicians, writers, and actors, enough so we could be each other’s fans. When I had concerts, painters would come, and I’d go play jazz at their art gallery openings, and I played piano while Beats read their poetry.”[1]

As a result of the artistic ferment in the Greenwich Village coffeehouse district by 1960, the neighborhood became the epicenter of the national folk music renaissance. Folk singers found ample work in some 20 clubs in a five-block area. Notable arrivals included Tom Paxton from Oklahoma, Len Chandler and Phil Ochs from Ohio, Carolyn Hester from Texas, Patrick Sky from Georgia, Mark Spoelstra from California, Judy Collins and Judy Roderick from Colorado, and Ian and Sylvia Tyson from Canada. In the smaller rooms, troubadours made little money, and talent agents rarely scouted them. But they saw the holes in the wall as starting points for the big time of the Gaslight and Gerde’s Folk City.[2]

Village venues allowed folk singers to hone their skills. For starters, the clubs afforded musicians the opportunity to experiment with new material and make mistakes in front of sympathetic yet discerning audiences. Sometimes in the intimate spaces they had to deal with rude hecklers or just simply people having loud conversations. Folk singers learned methods to hold a crowd’s attention. They launched records in clubs. They had a chance to gain a following. In the better clubs, folk singers encountered agents, managers, and record company executives. Critics from the New York Times or other publications occasionally reviewed performances in the premier Village venues.

* * *

Against this backdrop, in 1961, Bob Dylan from Minnesota arrived in New York. Though raised in the small mining town of Hibbing and just 19 years old, Dylan was hardly a greenhorn. A University of Minnesota dropout and a habitué of Minneapolis’s bohemian Dinkytown district, he had a seriousness of purpose that belied an outward shyness and a fluid identity. His decision to shun college and pursue art countered prevailing trends of the time.[3]

Ostensibly, Dylan, still legally Robert Zimmerman, went to New York to meet Woody Guthrie, his idol. Dylan’s bible was Guthrie’s autobiography, Bound for Glory (1943), a blend of fact and fiction about the Oklahoma troubadour’s travels across the United States with migrant workers uprooted by the Dust Bowl during the Great Depression. Taking his cue from John Steinbeck in The Grapes of Wrath (1940), Guthrie empathized with Okies, Arkies, and Texans devastated by the severe drought and the loss of their farms and documented their hardship in the agricultural sector of California’s economy. He also learned many of their folk songs.[4]

Bound for Glory startled and inspired Dylan, an impressionable college student uninterested in traditional education. Guthrie was multifaceted and rootless, impossible to categorize. At once, he was a singer and a poet, a worker and an organizer, a traveler and a writer, a vagabond and a refugee. Guthrie was a rugged individualist, a playful balladeer, and a sensitive humanist. He championed the downtrodden, the disinherited, and the displaced, celebrated the dignity of their labor, and spoke out for them when injustice occurred, whether perpetuated by unscrupulous bankers or exploitative bosses. In Guthrie, Dylan found his muse and spiritual forebear. “He’s the greatest holiest godliest one in the world,” Dylan exclaimed.

In his first year in New York, Dylan visited the ailing Guthrie, ravaged by Huntington’s chorea, in Greystone Park Psychiatric Hospital in New Jersey and in the home of folk enthusiasts Robert and Sidsel Gleason in East Orange. Guthrie suffered immensely, his hands trembled, his shoulders shook, and he was barely able to utter words. The Gleasons held Sunday gatherings for him, inviting friends to provide company. Ramblin’ Jack Elliott often attended, as did Cisco Houston. Dylan saw Guthrie numerous times and usually just sat in the room, watching, listening, and occasionally playing a tune.[5]

Dylan came to New York not only to commune with Woody Guthrie but also to plunge into the folk music scene, the nationwide epicenter of the revival. “New York City,” Dylan remarked, was “the city that would come to shape my destiny.” He did not know it but his timing was perfect. He poured himself into the creative ferment of the Greenwich Village coffeehouse district. Eager to broaden his horizons beyond folk music, Dylan saw foreign films at an art movie house on 12th Street and plays at the Living Theatre on Fourteenth. With Liam Clancy of the Clancy Brothers, he hung out at the White Horse Tavern on Hudson Street, enthralled by the Irish rebel ballads sung by men from the old country.[6]

Dylan became adept at navigating Village coffeehouses, playing at venues such as The Commons and Café Wha? and building a personal and artistic network in the process. His vulnerable look and scruffy appearance endeared him to many. In a folk music community that placed special value on instruction and apprenticeship, it did not take long for the needy and curious guitar and harmonica player to form a web of nurturing relationships. At Café Wha? on MacDougal Street, Dylan gained insight into the eclectic nature of Village entertainment. He often accompanied blues singer-songwriter Fred Neil on harmonica. Neil, an emcee at the Wha?, organized a potpourri of acts in the afternoon, featuring poets, comedians, magicians, hypnotists, ventriloquists, and more.[7]

But while the poorly lit club nourished the talent of the young Midwesterner, it lacked the prestige of other venues in the immediate area. On 116 MacDougal, across the street from the Wha?, for example, was the Gaslight Poetry Café, a venue that boasted a reputation for excellence in no small part because it was the stomping ground of folk singer Dave Van Ronk, who would become a crucial mentor of Dylan’s. A Brooklyn native, Van Ronk adopted Greenwich Village as his home in the 1950s. In Washington Square Park, he had learned finger picking techniques from experts like Tom Paley, Barry Kornfeld, and Dick Rosmini. He distinguished himself as the leading young folksinger on the scene by 1960. With an alternately fine and rough voice and an extensive repertoire consisting of jazz standards, Dixieland tunes, and blues hymns, the tall, gruff Van Ronk was embraced by Gaslight audiences and was dubbed the “Mayor of MacDougal Street.”[8]

In Minnesota, Dylan had listened to Van Ronk and copied some of his recordings. From Van Ronk’s repertoire, Dylan performed “Dink’s Song,” “House of the Rising Sun,” “Poor Lazarus,” and “See That My Grave is Kept Clean.” The two first met at Izzy Young’s Folklore Center, where Dylan played him “Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out.” Impressed, Van Ronk invited Dylan to sing a few songs in his set that evening at the Gaslight. Subsequently, Van Ronk and his wife, Terri Thal, helped Dylan and his girlfriend Suze Rotolo, a migrant from Queens, acclimate to the Village. Thal, the manager of Van Ronk and other folksingers, lined up several shows for Dylan. Dylan and Rotolo, living together on 161 West 4th Street, frequently visited the Van Ronks at their apartment on 180 Waverly Place to listen to records, to talk politics, to eat dinner, and play cards.[9]

Dylan’s other folk singing guru in the Village was Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Woody Guthrie’s greatest disciple. The son of a Brooklyn Jewish surgeon, Elliott was born Elliott Charles Adnopoz on, by his own account, “a 15,000 acre ranch in the middle of Flatbush.” Early in life, he acquired a love for cowboy movies and rodeos at Madison Square Garden and began to learn the guitar. While a student at Adelphi College, he heard Woody Guthrie’s records, and over the objections of his parents, he dropped out of school to become a folk singer. He also started to call himself “Buck Elliott” and eventually “Jack Elliott” to sound more like a westerner. In the late 1940s, Elliott met Guthrie in a hospital in Coney Island and became part of his family circle for a time. His goal was to play “Woody Guthrie songs exactly the way that Woody did.” Elliott was humorous, avuncular, and a great, though longwinded, storyteller – hence the nickname “Ramblin’.”

Elliott and Dylan instantly clicked. Elliott taught the younger man a number of songs and educated him about the cowboy-western tradition. He regarded Dylan as a devotee and sometimes when he covered his songs even announced to the crowd, “Here’s a song by my son, Bob Dylan.” Dylan also embraced the carefree drifter style of Elliott. But while Elliott fashioned himself in this manner in part to make people around him comfortable, Dylan played the role while concealing his extraordinary ambitions, something Ramblin’ Jack lacked.[10]

To satisfy those ambitions, he set his sights on playing Gerde’s Folk City, the premier venue in the nation, located on 11 West 4th Street. Mel Bailey, a regular customer at Gerde’s, and his wife Lillian lobbied Mike Porco, the owner of the establishment, to give Dylan a chance. Eve and Mac MacKenzie, two other patrons and parental figures to Dylan, also urged Porco to give Dylan a chance. Porco liked the idea. He supported new talent, not least because “the newer, the cheaper” was his financial strategy. After Dylan did well in a show for the New York University folk club on April 5, 1961, Porco’s interest increased. He signed Dylan for a two-week slot to open for the legendary Mississippi bluesman John Lee Hooker beginning April 11.[11]

Bob Dylan at Gerde's Folk City, October 3, 1961. From September 25 to October 8, 1961, Dylan played a series of shows at Gerde's, earning a rave review in The New York Times from music columnist Robert Shelton. Photograph by Irwin Gooen.

Gerde's Folk City, on the corner of West 4th and Mercer Streets in Greenwich Village, was a focal point of the folk music revival in New York. Photograph by Irwin Gooen.

Despite a professed abhorrence of schmoozing, Dylan excelled at a variant of it when he had to. He possessed an uncanny ability to engage others, not in casual conversation, but rather in clever, witty, and often pointed banter. He typically won his audiences over during performances, though some dismissed him as a Guthrie derivative. On stage, he usually wore a corduroy cap and was slightly and purposefully disheveled. He told corny stories between songs or sometimes just mumbled a few words. His voice had a nasal quality – thin, rusty, and grainy – suggesting at times Van Ronk, Elliott, and Guthrie but unique, seemingly rural in origins.[12]

As the buzz around him increased, Dylan met New York Times music critic Robert Shelton at a Monday night hootenanny at Gerde’s Folk City. In Shelton’s words, the “encounter was unforgettable.” Dylan did his quirky narrative song “Bear Mountain,” inspired by a Father’s Day boat cruise up the Hudson River that became a fiasco due to the sale of counterfeit tickets and overcrowding. After the set an impressed Shelton told Dylan to alert him about his next show and that he would try to review it in The Times. “I sure will, I sure will,” Dylan replied.[13]

Gerdes’ Mike Porco hired Dylan for two weeks, from September 25 to October 8, to play second act on a bill with the Greenbriar Boys, the talented city bluegrass group that consisted of Ralph Rinzler, John Herald, and Bob Yellin. The trio was a favorite with audiences at the club, their sets marked by whooping jams that showcased Herald’s nasal, boyish voice, Yellin’s dexterity on banjo, and Rinzler on mandolin. It was the proverbial hard act to follow. But Dylan rose to the occasion. On “I’m Gonna Get You, Sally Gal,” he alternated between guitar and mouth harp, keeping a fast tempo. His version of “Dink’s Song,” markedly different from Van Ronk’s, captured the emotional intensity of the original, recorded in 1909 by John Lomax, who heard an African American woman named Dink sing it on the banks of the Brazos River in Texas as she washed her man’s clothes. “Here’s a song outta my own head,” Dylan proceeded, called “Talkin’ New York.” Though an original composition, the song drew from Woody Guthrie’s unrecorded “Talking Subway Blues” and his outlaw ballad “Pretty Boy Floyd.” In a talking blues style, with a wry and sardonic touch, Dylan recollected his arrival in New York, referring to the challenges of landing gigs and gaining notice in Greenwich Village coffeehouses.[14]

Backstage, in the club’s kitchen, Shelton interviewed Dylan. “I was born in Duluth, Minnesota, or maybe it was Superior, Wisconsin, right across the line,” Dylan began, rattling off a series of untruths. “I started traveling with a carnival at the age of 13. I did odd jobs and sang with the carnival. I cleaned up ponies and ran steam shovels, in Minnesota, North Dakota, and then on south,” he explained. “I had the strange feeling he was putting me on,” Shelton recalled. About his performance manner, Dylan noted, “As to that bottleneck guitar, when I played a coffeehouse in Detroit I used a switchblade knife to get that sound. But when I pulled out the switchblade, six people in the audience walked out. They looked afraid. Now, I just use a kitchen knife so no one will walk out.” Shelton stared in disbelief.[15]

Shelton’s rave appeared in The Times on September 29, 1961, framed by a bold headline and a photograph of the performer with his hat, tie, and guitar. He started, “A bright new face in folk music is appearing at Gerde’s Folk City. Although only 20 years old, Bob Dylan is one of the most distinctive stylists to play in a Manhattan cabaret in months.” Shelton praised his proficiency on guitar, harmonica, and piano and compared his voice to the “rude beauty of a southern field hand musing in melody on his back porch.” Dylan was at once comic and tragic, slow in delivery but intense, poetic and yet at times scarcely coherent.[16]

The review caused a stir, not only catapulting Dylan to prominence in the city but also inspiring contempt among some folk singers and leading to a backlash against Shelton. Elliott, Van Ronk, and the Clancy brothers all applauded Shelton, remarking that Dylan richly deserved the tribute. But banjoists Eric Weissberg and Marshall Brickman, two fine instrumentalists, ridiculed Shelton for his inability to discern talent. Folk singer Logan English, struggling to make it himself, responded to Shelton’s view with sarcasm. The Greenbriar Boys were annoyed that the critic relegated them to an afterthought in the review. Songwriter and arranger Fred Hellerman, of the Weavers, saw Shelton on the corner of a street and blurted, “He can’t sing, and he can barely play, and he doesn’t know much about music at all. I think you’ve gone off the deep end!” In contrast, folk singers Carolyn Hester and Richard Fariña were enthusiastic. They admired Dylan and touted his skills as a harmonica player. Hester invited Dylan to play on her upcoming recording session at Columbia. The range of opinions mirrored the diversity of the folk music revival in the city, challenging the popular notion of a homogenous community.[17]

Dylan’s exposure increased steadily after the review, thanks partly to Izzy Young of the Folklore Center. Dylan often went to the MacDougal Street shop, spending hours in the backroom listening to records. He described the store as the “citadel of Americana folk music.” The loquacious and inquisitive Young chronicled some of the encounters in his notebook, jotting down pages of Dylan’s tall tales and scattered ramblings. “His questions were annoying, but I liked him because he was gracious to me and I tried to be considerate and forthcoming,” Dylan remembered. Young was happy to introduce Dylan to other influential figures in the New York folk music community, including Oscar Brand. Dylan did his first radio broadcast in the city on Brand’s Sunday WNYC show on October 29 in part to promote his first official solo concert, on November 4, organized by Young at Carnegie Chapter Hall. “He came on my radio show, and he said nothing but lies about his life,” Brand recalled. Typical of the farcical exchange was Dylan’s remembrance of traveling with the carnival during his teenage years and learning songs. “Where did you get your carnival songs from?” Brand asked. “Uh, people in the carnival,” Dylan replied. The concert itself, not in the Carnegie main hall, but in the debut room, was a modest affair, small and unmemorable. Only 53 people attended, and Young, charging $2.00 a ticket, lost money.[18]

During this pivotal fall, Dylan received a Columbia recording contract, a great milestone in his career, and though some observers assumed Shelton’s piece was the precipitating factor, Hammond had discovered Dylan before Shelton had. He first heard Dylan playing harmonica and guitar and singing harmony on some Carolyn Hester songs in her apartment for her debut album. He confirmed with Dylan that he was not recording for any label. The day after Shelton’s review, Dylan accompanied Hester for her recording session at Columbia in Midtown. On Dylan’s way out, Hammond asked him to come into the control booth to talk. He told Dylan that he wanted him to record for Columbia Records. The label was nationally prominent, strong in several genres, in contrast to the niche folk music companies Folkways and Elektra.[19]

Hammond was a transformative figure in Dylan’s life. As a producer and a talent scout, he championed jazz, spirituals, and blues, fueling the careers of Billie Holiday, Teddy Wilson, Charlie Christian, and Cab Calloway, among others. He practically singlehandedly revived the career of Delta bluesman Robert Johnson. Hammond gave Dylan a copy of the guitarist’s epic King of the Delta Blues, prior to its reissue on the Columbia label. The album floored Dylan. Hammond and Dylan conversed about Johnson and other giants of the music industry, including Pete Seeger. Hammond had recently brought Seeger to Columbia and was irate at the government’s blacklisting of him. “Hammond was no bullshitter,” Dylan recalled. “He explained that he saw me as someone in the long line of a tradition, the tradition of blues, jazz and folk and not as some newfangled wunderkind on the cutting edge.” Hammond put the contract in front of him, and Dylan signed straight away. “I trusted him,” Dylan reflected. “Who wouldn’t? There were maybe a thousand kings in the world and he was one of them.”[20]

Hammond wasted no time producing Dylan’s first album, titled simply Bob Dylan, recording it in just three sessions in November 1961 and releasing it on March 19, 1962. As he prepared for the tapings, Dylan immersed himself into the extensive record collection of Carla Rotolo, the sister of his girlfriend Suze and a personal assistant to Alan Lomax. Rotolo owned a substantial portion of the Folkways catalog as well as some Lomax field recordings. Only two songs on Bob Dylan, “Talkin’ New York” and “Song to Woody,” were original compositions. The rest were interpretations of traditional folk songs and blues, such as “Baby, Let Me Follow You Down” and “House of the Risin’ Sun.” Though the album received positive reviews in the Village Voice, Sing Out!, and Little Sandy Review, it was by most accounts a disappointment. Hammond recalled, “His guitar playing, let us say charitably, was rudimentary, and his harmonica was barely passable, but he had a sound and a point of view and an idea.” Dylan himself expressed embarrassment at the rushed effort, and the long delay between recording and release irritated him. The album did poorly in the marketplace. Fewer than 5,000 copies were sold in the first few months, prompting some Columbia figures to deride Dylan as “Hammond’s Folly.” For a moment Dylan considered quitting music. But Hammond and others in his Village circle encouraged him to persevere, reminding him that he was just 20 years old.[21]

Stephen Petrus, a historian at La Guardia and Wagner Archives, is co-author of Folk City: New York and the American Folk Music Revival (Oxford University Press, 2015). His next book will be a political and cultural history of Greenwich Village in the 1950s and 60s.

[1] Ed Glaeser, Triumph of the City: How Our Greatest Invention Makes Us Richer, Smarter, Greener, Healthier, and Happier (New York: Penguin Press, 2011), 1-15; Dan Wakefield, New York in the 50s (St. Martin’s Griffin, 1992), 7.

[2] Dave Van Ronk with Elijah Wald, The Mayor of MacDougal Street: A Memoir (Cambridge: DaCapo Press, 2005), 149-150; Bob Dylan, Chronicles: Volume One (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004), 16-18.

[3] Dylan, Chronicles, 9; Anthony Scaduto, Bob Dylan (New York: Signet, 1971), 36-38, 42-43.

[4] Joe Klein, Woody Guthrie: A Life (New York: Ballantine Books, 1980), 237-258, 441-451; Scaduto, Bob Dylan, 50.

[5] Robert Shelton, No Direction Home: The Life and Music of Bob Dylan, revised and updated by Elizabeth Thomson and Patrick Humphries (Milwaukee: Backbeat Books, 2011), 79-80; Todd Harvey, The Formative Dylan: Transmission and Stylistic Influences, 1961-1963, (Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 2001), 98-101; Scaduto, Bob Dylan, 60.

[6] Sean Wilentz, Bob Dylan in America (New York: Anchor Books, 2010), 1-14; Dylan, Chronicles, 9; Scaduto, Bob Dylan, 58.

[7] Dylan, Chronicles, 9-15.

[8] Van Ronk, Mayor of MacDougal Street, 13-25, 41-59, 141-156; Dylan, Chronicles, 15-16, 258-263.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Will Kaufman, Woody Guthrie: American Radical (Urbana, Chicago, and Springfield: University of Illinois Press, 2011), 183-196; Shelton, No Direction Home, 81-82.

[11] Robbie Woliver, Bringing It All Back Home (New York: Pantheon Books, 1986), 67-71; Shelton, No Direction Home, 76-77; Dylan, Chronicles, 64.

[12] Shelton, No Direction Home, 82-83; David Hajdu, Positively 4th Street: The Lives and Times of Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Mimi Baez Fariña, and Richard Fariña (New York: North Point Press, 2001), 75; Eric Von Schmidt and Jim Rooney, Baby, Let Me Follow You Down (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1994), 75.

[13] Ibid, 83.

[14] Dylan, Chronicles, 278; Shelton, No Direction Home, 84-85; Woliver, Bringing It All Back Home, 78-80; Harvey, The Formative Dylan, 109-110.

[15] Shelton, No Direction Home, 85-86.

[16] Robert Shelton, “Bob Dylan: A Distinctive Folk-Song Stylist,” NYT, 29 Sept. 1961, p. 31.

[17] Shelton, No Direction Home, 86-87.

[18] Dylan, Chronicles, 18-21;Scott Barretta, ed., The Conscience of the Folk Revival: The Writings of Israel “Izzy” Young (Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 2013), 193-195, 223-225; http://soundcheck.wnyc.org/story/wnyc-90-bob-dylans-first-radio-interview/

[19] Dylan, Chronicles, 278-279; Wilentz, 360 Sound, 182.

[20] Dylan, Chronicles, 5-6, 279-287.

[21] Shelton, No Direction Home, 87-95, 103, 115.