Cut-Throat: The Murder of William Lurye

By Andy Battle

On an average day at midcentury, New York City’s Garment District was a chaotic welter of sewing, schlepping, and schmoozing. But on May 12, 1949, the streets went silent for William Lurye, an organizer for the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU), the 400,000-strong body representing workers in the women’s clothing trade. Three days earlier, Lurye had been shoved into in a telephone booth in the lobby of a building on West Thirty-Fifth Street that housed dozens of loft-style garment factories. There, two assailants had stabbed the thirty-seven year-old father of four in the neck with an icepick.

The attack was public and brazen. ILGWU chief David Dubinsky lost no time in proffering a theory for Lurye’s murder. The organizer, Dubinsky said, had been “struck down in cold blood by murderers in the hire of anti-union sweatshoppers who would rather spill blood than carry on production in the sane and civilized manner to which the majority of garment employers are committed.”[1]

The wife of slain garment district worker William Lurye breaks down at his funeral in the Carmel Cemetery in Cypress Hills, Queens. She is supported by Charles S. Zimmerman, Vice President of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union. (Photo by George Torrie/NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images)

That Thursday, 65,000 garment workers walked off their jobs at 10am to protest Lurye’s killing. They formed part of a 100,000-person demonstration that watched silently as Lurye’s hearse traversed the stone canyons of the Garment District. Earlier, 20,000 had attended Lurye’s funeral at Manhattan Center, where the slain organizer’s body lay in state. Footage of the demonstration survives in the 1957 film The Garment Jungle, which dramatized Lurye’s murder, promising viewers “the whole shocking, sensational story of what goes on in the ten square blocks of gang-ruled jungle in the heart of New York.” At the time of Lurye’s funeral, his assassins remained at large, despite the 150 detectives the police department had assigned to the case.[2]

Lurye had been a dress presser, ironing garments as they left the factory on their way to wholesalers who scattered them across department store shelves. But he had recently taken a hundred-dollar-a-week pay cut to work as a special organizer for the ILGWU as it tried to bring the non-union dressmakers to heel. The word one heard most frequently in discussions of the garment industry was “cut-throat” — clothing manufacture was a notoriously competitive business, and some manufacturers would do anything to gain the fabled “edge” on their rivals. This meant evading the ILGWU, whose wage and benefit standards, while making no one rich, increased the labor costs of unionized firms. Among the services offered by Garment District racketeers was protection from these costs. For many owners, it was a rational business decision.[3]

What made Lurye take a sixty-five percent pay cut to accept a job that got him killed? The answer perhaps lay in his background. Lurye’s father Max had been a Chicago cigarmaker blacklisted for trying to organize his workplace. Now unemployable, Max turned to junk dealing, only to encounter a force even tougher than the employers—Al Capone. Capone sent associates to a meeting of the Junkmen’s Union to demand protection money. Max, screaming in Yiddish, led a revolt that ejected them from the stage. A few days later, Max and a friend were machine-gunned from an automobile on a Chicago street corner. Max survived — his friend didn’t. Capone’s gangsters didn’t let up. Eventually, they put three bullets into Max, who survived the attack at the cost of a leg amputated due to infection.

Max passed this incorruptible zeal on to his children — William’s sister Min, also an ILGWU organizer, became famous for her frontal challenges to organized crime in the non-union strongholds of northeastern Pennsylvania. But the assassination of his beloved son was too much for Max — a week after Willie’s funeral, the tough old man was dead, most believed of a broken heart.[4]

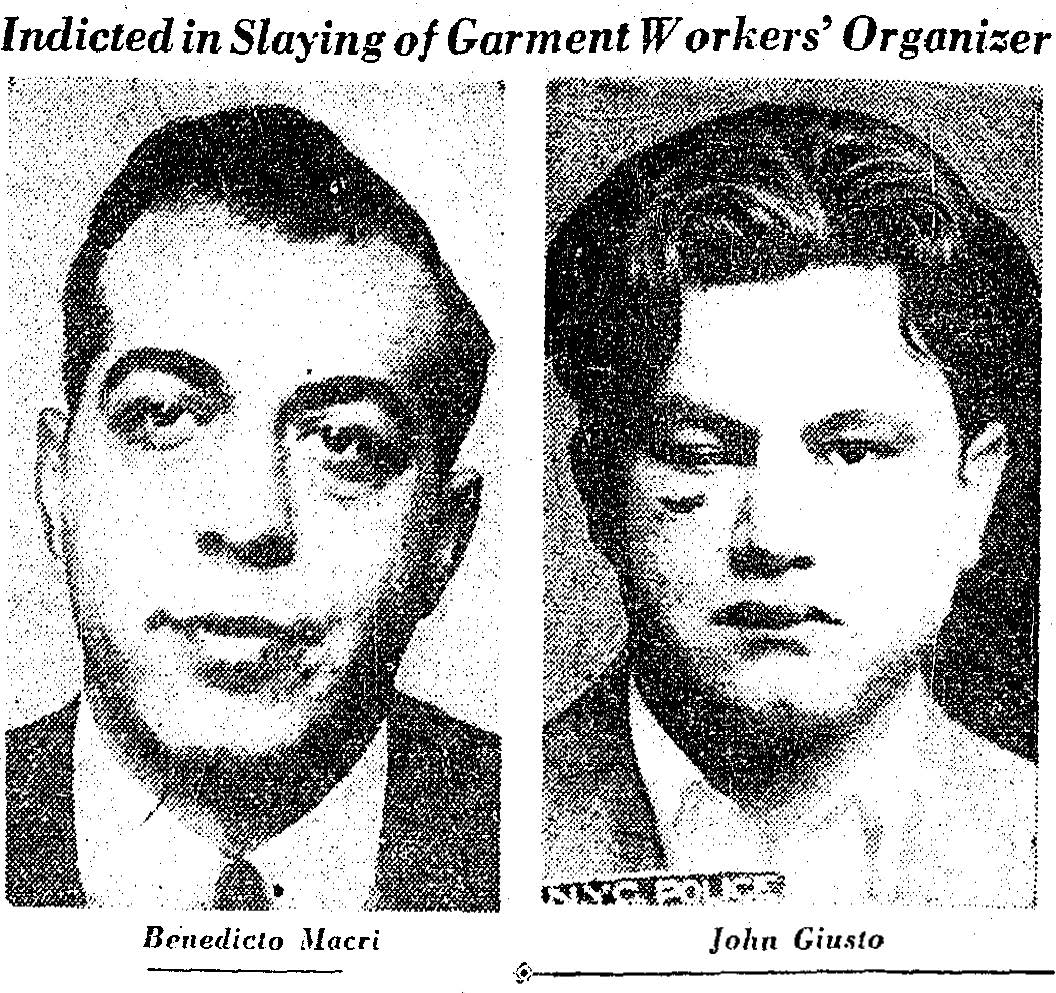

Despite a $25,000 reward offered by the union, Lurye’s killers remained at large for over a year. The investigation should have been simple, lamented District Attorney Frank Hogan. After all, the crime had occurred “in one of the busiest sections of our city in broad daylight.” But police and prosecutors confronted a wall of silence. Finally, after leaning on several Garment District habitués, Hogan announced a break in the case. Two men, Benedetto Macri and John Giusto, were indicted for the showy crime. Neither was anywhere to be found. Recriminations echoed up the political ladder — Republican mayoral candidate Newbold Morris accused Democratic incumbent William O’Dwyer, embroiled in a federal investigation that revealed his own ties to organized crime, of ordering the police department to “lay off” the Lurye investigation. Macri was eventually produced, but not by the police. In June 1950, columnist and radio host Walter Winchell announced dramatically over the air that Macri was prepared to surrender. That night, the journalist delivered Macri to the Twentieth Street police station. Winchell turned over the ILGWU’s $25,000 reward to the Damon Runyon Cancer Fund.[5]

Lurye's killers. Image excerpted from New York Herald Tribune, June 22, 1949.

Macri was a typical Garment District gangster. Like his patron, famed racketeer and “Murder Inc.” chieftain Albert Anastasia, he was a partner in a non-union dress business that sought its “edge” by keeping the ILGWU at bay. And like Anastasia, Macri maintained interests in the trucking firms that were the life’s blood — and chokepoint — of the dress industry. In legal strategy, too, Macri imitated the more famous man. Anastasia had famously beaten six murder charges when witnesses disappeared or delicately revised their testimony. When a jury acquitted Macri in October 1951, Judge Saul Streit complained of “strange incidents” that had attended the trial and had a prosecution witness, thirty-one year-old bookmaker Sam Blumenthal, charged with perjury after Blumenthal reversed earlier testimony in which he claimed to have witnessed Macri stab William Lurye. Later, during the sensational bribery trials that brought down Police Commissioner William P. O'Brien and O’Dwyer himself, Blumenthal revealed that he had accepted money to alter his testimony in the Lurye case. But the real reason for his change of heart, he explained, was that George “Muscles” Futterman, a business agent for the notoriously corrupt AFL Jewelry Workers Union, had warned him that “you’re as good as dead if you don’t do what you were told.”[6]

For men like Macri, Anastasia, and Futterman, violence was currency. Maybe it was the only currency these men, with their impoverished immigrant backgrounds and bursting ambition, could hope to wield. But their path was fraught with risk. At a victory party to celebrate Macri’s acquittal, Anastasia fled via the back door when gunmen seeking his death burst through the front. The bandit holed up in his palatial New Jersey home, rejecting friends’ advice to abandon New York for Hot Springs, Arkansas, a traditional hideout for New York gangsters looking to cool off. By 1954, the noose was closing around Macri and Anastasia. On April 26, a crowd of Bronxites watched as police extracted Macri’s brother Vincent, “one of Albert Anastasia’s closest associates,” from the trunk of a green-and-white convertible parked unassumingly on a quiet residential street. The next month, police found a car Benedetto Macri had borrowed parked by the Passaic River in New Jersey, the trunk stained with blood. And in October 1957, Anastasia met his end, shot to death in a barber’s chair at the Park Sheraton Hotel on Seventh Avenue.[7]

The cause for which Lurye had died — wrangling the non-union dress shops, eliminating their ill-gotten “edge,” and thereby restraining the race-to-the-bottom ethos that had bred misery for garment workers since the dawn of the trade — proved successful in the short run. But in a notoriously footloose industry, “open-shop gangsterism,” as the ILGWU called it, made for a moving target. A 1958 general strike in the dress industry, called for largely the same reasons, had a new geographical locus — the non-union “runaway” shops of northeastern Pennsylvania. As soon as the ILGWU corralled employers in a given region, new centers of production popped up. Before long, this game of whack-a-mole would cross national boundaries, putting the shops altogether out of reach of the ILGWU. By the 1970s, the union was in decline, and the sweatshop, to the horror of observers, had returned to New York, as new waves of immigrants accepted the miniscule wages necessary to compete with their counterparts in the less-developed countries.[8]

In the end, there was only a thin line between the Benedetto Macris and the so-called “legitimate” manufacturers. Both sought the same objective, and both used coercion — one overt, the other indirect — to grasp it. Lurye died fighting a rear-guard action against the brutal competition that drove manufacturers to violence. But the union for which he and so many others had sacrificed remained locked in a defensive approach whose feasibility faltered as manufacturers relocated across the country and the globe. Macri and Anastasia were replaced by other human incarnations of the competitive principle, people whose names English-speaking historians may never learn. They have been able to turn back the clock to the days of the sweatshops the ILGWU had done so much to dispatch.

Andy Battle is a PhD candidate at The Graduate Center (CUNY), and Associate Editor of Gotham.

Notes

[1] A. H. Raskin, “Job Stoppage Set in Murder Protest,” New York Times, May 11, 1949.

[2] A. H. Raskin, "Thousands at Funeral of Lurye Hear ILGWU Pledge War on Thugs," New York Times, May 13, 1949; The Garment Jungle, directed by Vincent Sherman and Robert Aldrich (Columbia Pictures, 1957).

[3] David Witwer, “The Dress Strike at Three Finger Brown's: The Complex Realities of Antiracketeering from the Union Perspective in the 1950s,” International Labor and Working-Class History 88 (2015): 166–89.

[4] Billy Rose, “Pitching Horseshoes,” New York Herald Tribune, June 27, 1949.

[5] “Hogan Assails Those Balking Lurye Inquiry,” New York Herald Tribune, June 23, 1949; “Mayor Calls Rivals ‘Cozy Team,’” New York Herald Tribune, November 2, 1949; “Lurye Slaying Suspect Enters Not Guilty Plea,” New York Herald Tribune, June 20, 1950.

[6] “Macri Cleared On Charge of Slaying Lurye,” New York Herald Tribune, October 30, 1951; “Graft Trial Hears Eyewitness Name 2 as Lurye Slayers,” New York Times, August 2, 1952; “Bribe Demand Admitted,” New York Times, December 13, 1952.

[7] “2 Attempts to Kill Anastasia Reported,” New York Times, November 21, 1951; “Gangland Tells Anastasia to Get Out or Die,” New York Herald Tribune, November 21, 1951; Wayne Phillips, “Anastasia Henchman Found Slain in Auto,” New York Times, April 26, 1954; Newton H. Fulbright, “Benedetto Macri Mystery: Is He Murdered or Hiding?,” New York Herald Tribune, May 3, 1954; Meyer Berger, “Anastasia Slain in a Hotel Here,” New York Times, October 26, 1957.

[8] “I.L.G.W.U. In Drive Against Open Shop,” New York Times, May 6, 1952; Kenneth C. Wolensky, Nicole H. Wolensky, and Robert P. Wolensky, Fighting for the Union Label: The Women’s Garment Industry and the ILGWU in Pennsylvania (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2002), 161–85; William Serrin, “After Years of Decline, Sweatshops are Back,” New York Times, October 12, 1983.