Daisy Chanler, Father Sigourney Fay & F. Scott Fitzgerald

By Margaret A. Brucia

"F. Scott Fitzgerald," by David Silvette, 1935, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

On November 6, 1918, three days after the Armistice of Villa Giusti, which ushered in a ceasefire on the Italian Front between Italy and Austria-Hungary, Mary wrote to her mother, Julia Gardiner Gayley, describing the celebration in the center of Rome. Mother and daughter had been separated by the war for four years.

"[We saw] sailors, students etc. shouting 'Morte ai Tedeschi' [Death to the Germans] in a cadenced, foot-ball 'rooting' measure they must have learned from the Americans! Flags were everywhere, & all the people en fête, the streets packed....

It seemed like a dream, & still does — The war is not ended, & in fact all the papers are united in repeating that & that Italy will go on under orders ([Marshal] Foch’s) as firmly as before, but to the great mass of the people it means peace — & no danger of air raids, & probably the swift return of prisoners.... I cannot help making plans & they spell “Julie in March or April”!! and for a long, long visit.

Oh Julie, Julie, what days! We are all gray & tired.... I always knew peace would be like a blow on the head in its too sharp release from tension."[1]

This is the latest in a series of posts based on the letters of the New York socialite, Julia Gardiner Gayley (1864-1937), to her eldest daughter, Mary Gayley Senni (1884-1971), a countess who lived on the outskirts of Rome. In 2010, the author purchased a trove of the letters in a Roman flea market. This mother-daughter correspondence spanned the years 1902-1936 and provides an intimate and unfiltered view of life in New York during the early twentieth century. You can find the earlier posts on our homepage.

Mary’s letter arrived at Washington Square five weeks later. On December 11, ambivalent about the efficacy of America’s delegation to the upcoming Paris Peace Conference, Julie replied to her daughter.

"Dearest Mary,

I have your letters of November 3rd and [6]th. They are wonderful letters that I shall always keep. You have felt the great thrills of the War.... I wonder if when Wilson gets to Europe it will not vaguely begin to dawn on him that the issues of the War are to be decided by men who have lived through days, and months and years of a tension which no one over here could even dimly divine."[2]

In the same letter, Julie informed her daughter that she and her friend Daisy had gone to Carnegie Hall two days before to hear a talk by Monsignor Sigourney Webster Fay. An Episcopal convert to Catholicism and former chaplain to Cardinal James Gibbons of Baltimore, Fay had served as emissary of the Red Cross in Italy during the war. "I went with Daisy Chanler in her box and afterwards we met him at luncheon at her house. He is strong for Wilson, strong for extreme democracy, and radical change."

Wintie Chanler with his wife Margaret (“Daisy”) Terry, and their first two children, John Winthrop (left) and Laura Astor Chanler. Photographed in Rome, ca. 1890. Source: Lately Thomas, The Astor Orphans: Pride of Lions (Washington Park Press, 1999).

Who was Julie’s little-remembered companion, Daisy Chanler, and what was Daisy’s relationship with the speaker, Monsignor Sigourney Fay?

Margaret Terry Chanler was nicknamed “Daisy."[3] Two years older than Julie, she was fifty-six in 1918. Edith Wharton described her childhood friend as “dear & wonderful, serene & unhurried.”[4] Henry Adams greeted her effusively in his letters as “gentle saint,” “Model-of-Women,” “Lady of Light,” “Teacher,” “Guide,” his “only Idol.”[5] Henry James wrote that Daisy was “a resource — emotionally” to him.[6] Theodore Roosevelt, a close friend of Daisy’s husband, was the godfather of her youngest child.[7] And, according to one theory, F. Scott Fitzgerald paid homage to both Daisy Chanler and Monsignor Fay by naming the heroine of The Great Gatsby Daisy Fay Buchanan.[8]

Born in Rome to expat parents, Daisy enjoyed a charmed and privileged childhood.[9] Well educated by governesses and private tutors, she became equally fluent in French and German, but Italian remained her default language, and consequently her English bore traces of an accent. Daisy cultivated her innate love of music and contemplated a career as a professional pianist. Though raised Episcopalian, at the age of twenty she converted to Catholicism and embraced her new religion with a convert’s zeal. Daisy would have lived contentedly in the Eternal City for the rest of her life, had she not met and married, in a whirlwind romance, her gregarious, magnetic and persistent second cousin, Winthrop (“Wintie”) Astor Chanler, the second oldest of ten orphaned siblings, known collectively as the Astor orphans.[10]

The ‘Astor orphans’ and their cousin Mary Marshall at the family estate, Rokeby. From left: Willie, Alida, Archie, Elizabeth, Wintie, Mary Marshall, Lewis, Margaret and Bob. (Photo c. 1884)

A man of impulse and action — and of considerable financial means — twenty-year-old Wintie wasted no time courting his twenty-two-year-old cousin, to whom he had become attracted two years before during a family visit. Daisy and Wintie were engaged in September 1886 and were married in Rome on December 16, despite three major obstacles: their consanguinity, Wintie’s religion (Episcopalian), and the Church’s prohibition of marriage during Advent. Three papal dispensations later, Daisy and Wintie were husband and wife.

Rokeby Farm (Daisy & Wintie’s first home)

By June of 1887 the newlyweds were ensconced at Rokeby, the Chanler family’s communal estate on the Hudson, where they lived with Wintie’s younger siblings. The following autumn they were gone. Leaving Italy was difficult for Daisy, but life with Wintie’s intolerant family at Rokeby was unbearable. Reviled for her Catholic faith, Daisy was alternately ignored and criticized by her in-laws. In her memoir, Roman Spring, Daisy bitterly and unapologetically faulted Wintie’s family for leading “a desperately meagre life with a great sense of their own importance.”[11]

The Chanlers next established themselves in Washington D.C., where Daisy, bruised but triumphant, gained easy acceptance into elite Catholic society. Although the precise moment is unclear, sometime during their Washington years the Chanlers befriended Father Fay, a prominent member of Catholic high society.

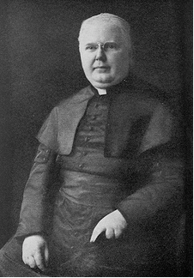

Father Fay

Perhaps best known through his connection to F. Scott Fitzgerald, Fay’s background remains something of an enigma. He and Fitzgerald met during the years 1911-1913, when Fitzgerald was a student at the Newman School, a Catholic prep school in Hackensack, New Jersey. Then a priest in his late thirties, Fay recognized and nurtured the teenaged Fitzgerald’s talent for writing. He became both a father figure and mentor to the boy. So powerful was Fay’s influence on Fitzgerald that the young author immortalized him in his debut novel, the semi-autobiographical This Side of Paradise, published in 1920. Fay was both Fitzgerald’s dedicatee and his model for the character Reverend Thayer Darcy.

How could investigation into the life of a man who exerted such a significant influence on one of America’s greatest authors yield such scanty information? The Newman School was founded in 1900 and shut its doors permanently in 1941. Regrettably, its records, which likely would have yielded clues about both Fitzgerald and Fay, are lost. As a result, the only way to glean information about the author’s Newman years and his early relationship with Fay is to mine Fitzgerald’s personal papers or to derive facts from his fiction (a dangerous practice at best).[12]

But, of course, the Chanlers were another link to Fay, and Daisy, in her memoirs, highlighted his personality and revealed a few details of his life. In 1904 the Chandlers and their seven children relocated from Washington to the Genesee Valley, where they purchased a sprawling 160-acre estate, Sweet Briar Farm, an idyllic setting for Wintie’s favorite pastimes — riding and foxhunting.[13] Not surprisingly, one of Daisy’s first projects was to oversee construction of a chapel on the grounds, dedicated to St. Felicitas. Tapping into her friendship with Fay, she extended an open invitation to Sweet Briar Farm and asked him to serve as their domestic chaplain.

Sweet Briar Farm

A frequent guest, Fay, according to Daisy, was “a great favorite with Cardinal Gibbons, and was in some way attached to his household.”[14] She described Fay as “tall and exceedingly fat” and reported that his “mother came from a good Irish family and had transmitted to him the attractive speech of the cultivated Irish.”[15] She provided glimpses of a jovial and relaxed Fay interacting with his “adoptive” family. "Father Fay had no parish of his own and used to say that we were his parish. He was one of those guests who know how to add a certain zest to the routine of family life, to make the waters bubble and sparkle; he kept us, as Wintie used to say, 'on the holy hop.'"[16] And furthermore, "He was a learned man with much of the delightful child about him. He combined spiritual with temporal gifts, for he preached admirably, and could bring fire from heaven to kindle the hearts of his hearers, but he was no ascetic and dearly loved good company, good food and good drink.”[17]

About Fay's involvement in the Great War, again, Daisy is our best source. "When America went into war he volunteered.... [H]e wore a khaki uniform over his vast bulk and did not mind looking slightly ridiculous; he was sent to Rome, where he was often received by Pope Benedict XV, who liked him well and promptly made him a domestic prelate of the apostolic household with the title of Monsignor. Wintie was in Rome at the time [serving as wartime aide to General Pershing] and the two feasted together at a famous osteria."[18]

Father Fay was something of a dandy. Shortly after his return from the Vatican in 1918, he could hardly wait to show off his new monsignorial raiment to Daisy and her family at Sweet Briar Farm. Adorned in a rustling purple-pink faraiuolo (cloak) over his purple cassock with carmine piping and carmine buttons, a purple-pink biretta atop his balding pate, Daisy reported that “he looked like nothing so much as an enormous peony floating about.” But he was as pleased as “a little boy showing off a suit of shining armor just received from Santa Claus.”[19]

A few months after Father Fay’s fashion show, Daisy and Julie were on their way to Carnegie Hall to hear him speak. Daisy undoubtedly was predisposed to agree with everything her beloved friend had to say; Julie, an Episcopalian, however, was a little more skeptical.

An apologist for Pope Benedict XV for his failure to condemn German aggression during the war, Fay argued that the pope, as an international religious leader, had a responsibility to maintain neutrality. Moreover, he proposed that the pope be given a voice at the Paris Peace Conference.[20] But Julie, a harsh critic of Wilson for his reluctance to speak out sooner and more forcefully against the Germans and for his dalliance in committing American troops to war, would have none of it.

In her letter of December 11, 1918, Julie offered this recap of Fay’s lecture:

"Curious, is it not? He advocates the sitting of the Pope at the Peace table by a representative of course, and says he supposes other forms of faith will desire the same representation. He says there were no wars in Europe to amount to anything so long as Christendom was a unit of which the Pope was the head with power to approve or disapprove the actions of peoples, and that only after the Reformation and the modern spirit did fierce national struggles begin, unsubdued by any higher power. The inference is, that with the Pope again functioning with authority in a League of Nations the same happy state of things might return."[21]

Julie viewed Fay’s interpretation of history as not only simplistic, but impossibly idealistic.

"I have never heard more naïve presentations of history than he set forth. It strikes me that Europe has with too much blood and tears accomplished the divorce of Church and State to be ever likely to return to it. Herasy, [sic] however regrettable, had done its work, and if the Pope had forbidden Catholic America to fight there would have been a pretty Church-State mess. The present Pope simply did not rise to his high and unique opportunities. I, myself, can see many reasons why it should not have appealed to him, but what a wonderful thing if it had."

Unfortunately, we have no record of the conversation that ensued between Daisy and Julie, two equally opinionated and strong-willed women, as they left the lecture, nor, for that matter, of any discussion between Julie and Fay at the luncheon that followed. Could the day’s event have strained the friendship between Daisy and Julie?

There was little opportunity for Julie and Daisy to disagree about future ideas put forth by Fay. Within a month, the jolly priest was dead, having succumbed suddenly on January 10, 1919, to pneumonia.[22] Fay was in his early forties. Teddy Roosevelt died just four days before Fay. And so Daisy’s joy at the return of her husband from the war was tempered by the death of two close friends.

Saddened as Daisy was, Fitzgerald was devastated by Fay’s death and, in a letter to his friend Leslie Shane, he paid Fay the highest tribute, “I can’t tell you how I feel about Monsiegneur Fay’s death — He was the best friend I had in the world....”[23]

Fitzgerald knew Daisy through Fay, but he also traveled in the same social circle as Teddy Chanler, Daisy’s youngest child, a talented composer.[24] His relationship with the Chanlers continued after Fay’s death. When Edith Wharton invited Fitzgerald to tea at her home outside Paris in 1925, Teddy accompanied him. (Fitzgerald, having had too much to drink beforehand, was unable to carry on a conversation with the notoriously shy and difficult Edith. Unimpressed by the author of The Great Gatsby, Edith recorded the event in her diary by writing one word — “Horrible” — next to Fitzgerald’s name.)[25]

ulie and Daisy also stayed in contact after Fay’s death, but their friendship cooled in the early 1920s. On August 22, 1922, for example, Julie wrote to Mary from Maine that she had invited Daisy and another female friend to lunch. When she realized that a Catholic priest, whom Daisy knew well, was in the area, she asked him to join them. But, once the priest learned that Daisy was one of her guests, he declined. The reason, Julie wrote: “[He] sincerely doesn’t like her.”[26]

Four months later, this time from Paris, Julie related to Mary two more unflattering incidents involving Daisy. A mutual acquaintance told Julie in confidence that “people didn’t like her air of being enormously important, as if all other Americans were dirt.” And when one of Julie’s friends mentioned Daisy to the painter Jacques Émile Blanche, he responded, or so Julie was told, “’Don’t talk to me of Mrs Chanler — She is very superficial — not at all like Mrs Dunn.’” (By this time, Julie had married her second husband, Gano Dunn.) Afraid of having her unkind stories discovered among the letters she knew Mary saved, Julie added, “Tear up this letter — but I thought these things would amuse you.”[27]

Just as Daisy’s memoirs reveal a lighter side of Fay, Julie’s letters reveal a darker side of Daisy. Let us never underestimate the value of personal memoirs and unfiltered letters. They enable us to flesh out details and to capture subtle nuances that might otherwise be lost or buried by time. Fortunately, Mary was not always an obedient daughter. She saved her mother’s letters — all of them — even the ones she was told to destroy.

Margaret A. Brucia has taught Latin in New York and Rome for many years and is a Fulbright scholar, the recipient of a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Humanities, and a Fellow of the American Academy in Rome.

Notes

[1] Mary Gayley Senni to Julia Gardiner Gayley, November 6, 1918, author’s collection. Four months after I discovered the large cache of Julie’s letters in a Roman flea market, I met several of Julie’s relatives and descendants in Maine. Unaware of the existence of Julie’s letters to Mary, they were pleased that I had rescued and preserved them. Julie’s great-granddaughter, Vittoria McIlhenny, shared photographs of Julie and her family with me and gave me a copy of Mary’s unpublished memoir, written when she was in her seventies. Four years later, I received a telephone call from Vittoria. While she and her brother were preparing to move an old desk from the attic, they opened a drawer. Inside were six neatly arranged files of letters. From Mary to Julie — the other half of my original correspondence.

[2] Julia Gardiner Gayley to Mary Gayley Senni, December 11, 1918, author’s collection.

[3] Romance language versions of the name Margaret — Marguerite in French, Margherita in Italian, and Margarita in Spanish, e.g. — are the same as the words in those languages for a daisy.

[4] Edith Wharton to Sara Norton, August 29, 1902, in The Letters of Edith Wharton (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1988), 67.

[5] For Henry Adams's salutations to Margaret Chanler, see "Margaret Chanler family papers, 1815-1939: Guide,” Harvard University Library, Online Archival Search Information System,

http://oasis.lib.harvard.edu/oasis/deliver/~hou00334 .

[6] Henry James to Edith Wharton, January 16, 1905, in Henry James: Letters,Vol. IV (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press, 1984), 342.

[7] Mrs. Winthrop Chanler, Autumn in the Valley (Boston: Little Brown and Company, 1936), 21.

[8] Andrea Olmstead, Who was F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Daisy? (Smashwords, 2012). This non-paginated eBook draws links between F. Scott Fitzgerald, Father Fay and Daisy Chanler and provides an overview of their lives.

[9] Daisy’s memoirs, Roman Spring (Boston, Little, Brown and Company, 1934) and Autumn in the Valley (see note 7 above) are the sources of details about Daisy’s life. She published both books under the name of Mrs. Winthrop Chanler.

[10] See Lately Thomas, The Astor Orphans: A Pride of Lions (Albany: Washington Park Press, 1999) for more information on the Astor orphans.

[11] Roman Spring, 188.

[12] Pearl James in F. Scott Fitzgerald in Context, ed. Bryant Mangum (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 115.

[13] The Chanlers had eight children, but their second child died in childhood. The oldest child, Laura Astor Chanler, married Stanford White’s son, Larry; the youngest child, Theodore Ward Chanler, married Maria de Acosta Sargent, one of Rita Lydig’s sisters.

[14] Autumn in the Valley, 78.

[15] Id., 81.

[16] Id., 78.

[17] Id., 80.

[18] Id., 82-83.

[19] Id., 84.

[20] "Pope Favors Peace League,” New York Times, December 10, 1918.

[21] This and the following excerpt are taken from Julia Gardiner Gayley to Mary Gayley Senni, December 11, 1918, author’s collection.

[22] "Mgr. Sigourney W. Fay Dies,” New York Times, January 11, 1919.

[23] F. Scott Fitzgerald to Leslie Shane, January 13, 1919, in F. Scott Fitzgerald: A Life in Letters, ed. Matthew J. Bruccoli ((New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons), 21.

[24] Mary Jo Tate, Critical Companion to F. Scott Fitzgerald (New York: Facts on File, 1998, 2007), 276.

[25] Andrew Turnbull, Scott Fitzgerald (New York: Grove Press, 1962), 153-54.

[26] Julia Gardiner Gayley to Mary Gayley Senni, August 22, 1922, author’s collection.

[27] All of the quotations in paragraph from Julia Gardiner Gayley to Mary Gayley Senni, late November 1922, author’s collection.