Fighting World War One on the Streets of New York

By Ross J. Wilson

In 2017, the hundredth anniversary of the entry of the United States into World War One will be marked but for New York this date should not carry the same resonance as it might for other parts of the nation. For whilst the United States went to war in April 1917, the city had been enmeshed in the fighting since the very outset in August 1914. The war radically altered New York, redefined its communities and forged an 'American' city from a diverse metropolis.

By 1900, New York’s foreign-born population included:

300,000 Germans

155,000 Russians

30,000 Polish

275,000 Irish

145,000 Italians

117,000 Austro-Hungarians

90,000 British

With a high proportion of first and second generation immigrants, the 1900 and 1910 Censuses recorded a ‘native’ population, of those with one parent born in the United States, as only 50-60%. African Americans in New York numbered over 60,000 and a small population of Chinese Americans resided in the city.

Therefore, in New York, ‘German’was the largest ethnic group. This status was reinforced with the presence of Klein Deutschland in the Lower East Side where German banks, businesses and newspapers flourished. Other ethnic, religious and national enclaves also dotted the city. Indeed, by 1900 New York appeared to critical commentators as a city of ‘foreign villages’.

Such perceptions were reinforced as Europe went to war in August 1914 and New Yorkers promoted the cause of combatant nations. The German-language New Yorker Staats-Zeitung extolled the virtues of the Kaiser, the Yiddish socialist Forverts condemned the autocracy and anti-Semitism of Tsarist Russia, the Slovakian paper Slovák v Amerike considered the potential for a Slavic state with the fall of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire, and the Gaelic American demanded Irish liberty as Britain’s colonial rule forced Ireland into the war.

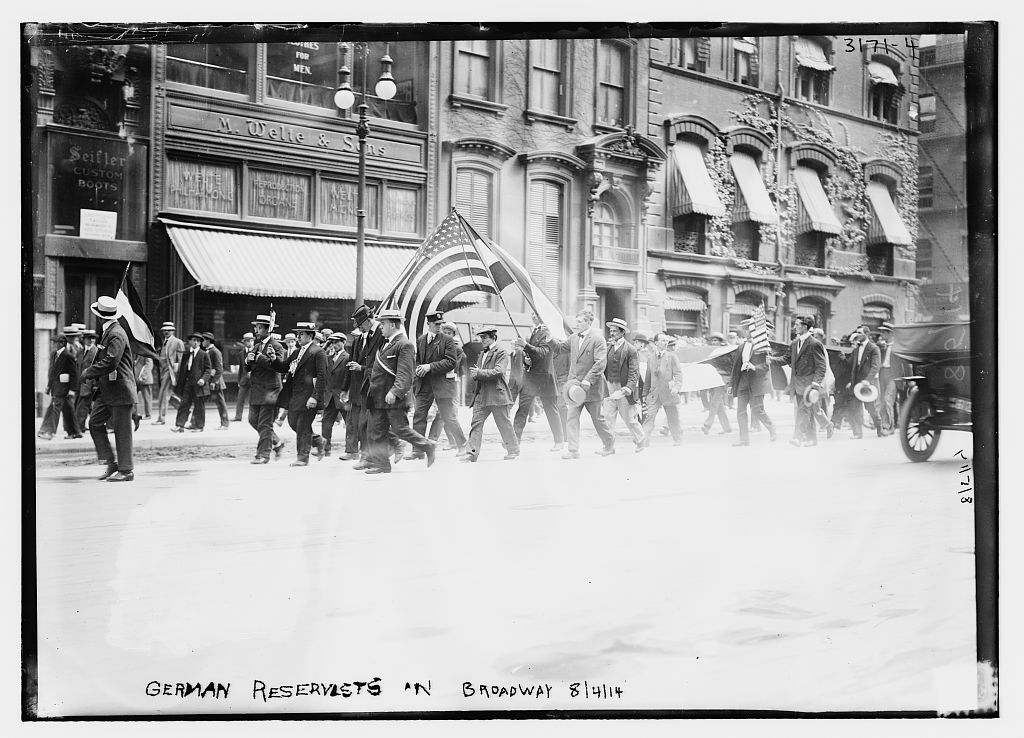

In the heat of early August, crowds gathered in Times Square and Herald Square to hear the latest news from the battlefields, cheering as reports of victories or advances were announced. The consuls of foreign states within the city also encouraged patriotic fervour for the ‘old country’. This call was met by German Americans who paraded down Fifth Avenue and appeared at consul offices to enquire when they could be transported back to fight. Similarly, within those ethnic enclaves, fund-raising schemes were also formed for orphans and widows as a means of expressing attachment.

The potential for New York’s diverse population to act as a tinderbox for the nationalist conflict that had engulfed Europe forced the city’s mayor, John Purroy Mitchel (1879-1918), to issue a city ordinance on August 6 to remove any display of national devotion beyond that for the United States:

Public demonstrations of sympathy by people of a particular race, while natural from their point of view, are calculated to breed ill feeling upon the part of their fellow-citizens of other blood and sympathies and should not take place in this cosmopolitan and entirely neutral city.

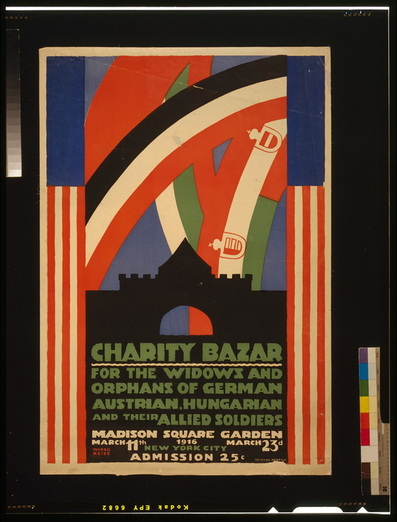

The effect of this control is witnessed in the charitable causes that were initiated in the city. For example, a charity bazaar organised for the widows of Germany, Austria and Hungary in the 71st Armory on 34th Street and Park Avenue proclaimed a ‘German American union’. Germans who had fought in the War of Independence were commemorated in the bazaar in the naming of DeKalb, Steuben or Leisler Streets. Further events were held in the city for the Central Powers and for the Entente in 1916.

The actions of groups supporting the war efforts of other nations were increasingly under suspicion from the Mayor’s Committee on National Defense formed in October 1915. This committee was concerned with the patriotism of ‘foreign’ sections of New York. Pre-war concerns regarding the loyalty of an ‘alien city’ were also raised by this organisation.

With the sinking of the Lusitania in April 1915 by the Germany navy, the attempted murder of J.P. Morgan by a German immigrant in July 1915, the formation of the pro-war Preparedness Movement in New York in August 1915 and the rise of the quasi-paramilitary National Security League (NSL) in the city after September 1915, the identities of New Yorkers were closely observed.

In such an atmosphere, New Yorkers began to proclaim their commitment to the nation. The Preparedness Parade on May 13, 1916, saw an estimated 130,000 people attend the procession along Fifth Avenue. Marchers paraded beneath a banner that stated ‘Absolute and unqualified loyalty to our country’. The demand for loyalty was reinforced after the Black Tom Island Explosion on July 30 1916, where a depot of ammunition and supplies bound for Europe was sabotaged by incendiary devices destroying the site itself and damaging buildings in Downtown Manhattan. Whilst the culprits were not found, the event served to heighten suspicion of German radicals within the city.

To encourage patriotism, the Mayor’s Committee on National Defense launched an initiative in early February 1917 to collect one million signatures from New Yorkers with the following petition:

As an American, faithful to the American ideals of justice, liberty and humanity, and confident that the government has exerted its most earnest efforts to keep us at peace with the world, I hereby declare my absolute and unconditional loyalty to the Government of the United States…

The petition was placed in hotels, bars, telegraph offices, municipal offices, political party branches, as well as police stations. New Yorkers were able to state their allegiance whilst completing their daily tasks. Outbreaks of civil disorder, such as the Brooklyn Food Riots of February 1917, caused by wartime blockades and the rise in prices of consumables, could now be tarred with the accusation of sedition.

With the resumption of German submarine warfare in February 1917 and the declaration of war by the United States in April 1917, the transformation of New York could be seen across the city. Previously pro-German publications such as the New Yorker Staats-Zeitung stated their allegiance to the United States. Socialist and anarchist newspapers and periodicals were restricted and monitored, including Forverts. Indeed, the news of revolution in Russia in March 1917 prompted Mayor Mitchel to state to a Russian American gathering in the city that all citizens could be divided into two classes, ‘Americans and traitors’.

The Mayor’s Committee coordinated ‘Wake Up, America Day!’ on April 19 1917. This commenced with a recreation of the ride of Paul Revere through the city as the bells of Trinity Church were rung. Floats depicting scenes from American history and banners proclaiming the loyalty of citizens were part of this extensive rally, which also saw businesses and shops along Fifth Avenue decorated as part of the patriotic spectacle.

The introduction of the Selective Service Act in May 1917 intensified the level of observation of identity within the city as the spectre of the 1863 Draft Riots haunted politicians. Registration for the draft in the city was accompanied by the heavy physical presence of authority. The city’s police were accompanied in their duties by the NSL. Such was the status of the NSL that by July 1917, they begun to issue letters to German American groups, including the Germania Society in Brooklyn or the German Historic Society, requiring their members to denounce the German government and declare their allegiance to the United States.

Within this demand for loyalty in the city, the nature of citizenship was also questioned. In response to the racially-motivated murders in East St. Louis on July 3 1917, the NAACP and African American churches in Harlem conducted a ‘Silent Protest’ on July 28 1917. Participants in the protest carried banners and placards that directly alluded to the contradiction of asking African American men to fight for freedom in Europe whilst they were being deprived of representation, assaulted and murdered at home.

With the patriotic fervour encouraged by the Liberty Loan campaigns in 1917 and 1918, a significant alteration of New York could be witnessed. German businesses and shops changed their trading names to avoid being accused of disloyalty:

The German American Building and Loan Association of the City of New York, became, The Enterprise Savings and Loan Association

The German American Bank, became, The Continental Bank of New York

Germania Savings Bank, Kings County, became, the Fulton Savings Bank, Kings County

German Savings Bank of Brooklyn, became, The Lincoln Savings Bank of Brooklyn

Germania Life Insurance Company, became, the Guardian Life Insurance Company

The German Savings Bank in the City of New York, became, Central Savings Bank in the City of New York

Later in 1918, the German Hospital and Dispensary, which had constructed the Kaiser Wilhelm Pavilion in 1913, was renamed the Lenox Hill Hospital by its Board of Trustees.

By November 1918, the city had been altered as it demonstrated its ‘American’ character. The celebrations that marked the end of the conflict reflect these changes. Whereas in 1914, German Americans had paraded down Fifth Avenue proclaiming their attachment to the Fatherland, in November 1918 mobs kicked effigies of the Kaiser through the city. The fervour in which many New Yorkers responded to the news of the end of the war emphasises how the war had made Americans out of New Yorkers.

Ross J. Wilson is Senior Lecturer in Modern History and Public Heritage at the University of Chichester (UK). He is currently working on a study of civic culture in nineteenth century New York.

Further reading

The assessment of New York during the First World War can be read in Ross J. Wilson’s New York and the First World War (2014).

Detailed assessments of immigrant communities response to the conflict can be found in Christopher M. Sterba’s Good Americans: Italian and Jewish Immigrants During the First World War (2003) and Christopher Capozzola’s Uncle Sam Wants You: World War I and the Making of the Modern American Citizen (2008).

Specific works on New York’s battalions can be found in Jeffrey T. Sammons and John H. Morrow Jr., Harlem's Rattlers and the Great War: The Undaunted 369th Regiment and the African American Quest for Equality (2015) and Richard Slotkin's Lost Battalions: The Great War and the Crisis of American Nationality (2005).

The definitive works on the United States during the First World War are David M. Kennedy’s Over Here: The First World War and American Society (1980) and Jennifer D. Keene’s Doughboys, the Great War, and the Remaking of America (2001).