For an Irish National Theater in New York

By Catherine M. Burns

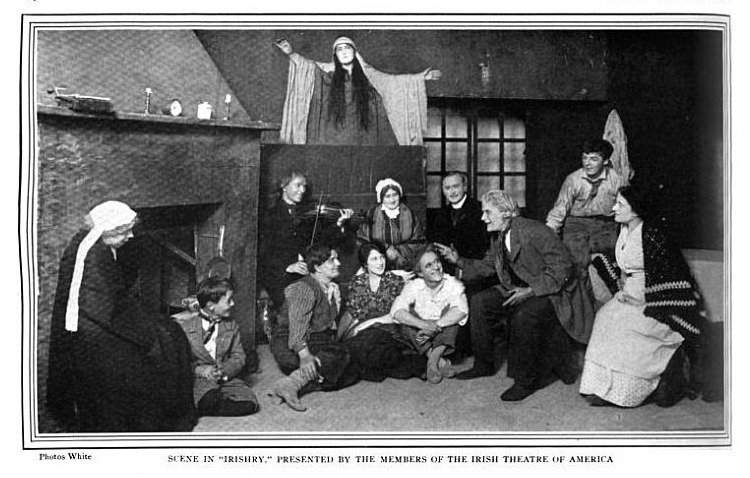

Between 1915 and 1920, three short-lived companies in New York City calling themselves the Irish Theatre of America, the Celtic Players, and the Irish Players tried to establish an Irish national theater. They modeled themselves on the Ulster Literary Theater of Belfast and the Abbey Theater in Dublin. Their existence speaks to the transatlantic nature of the rise of modern Irish drama. But little is known about their efforts.

Proponents of the national theater movement in early twentieth-century Ireland put on plays challenging stereotypes on the dominant English stage with counter depictions of Irish history, people, and culture. The national theaters showed that Irish identity was unique from the English and provided a model of Irish solidarity against a sea of internal political, religious, and class differences. Dublin’s Abbey tended to locate Irish identity in the rural west. The Belfast company centered on people, culture, politics, and experiences unique to Ireland’s north.[1]

Yet what succeeded in Ireland did not satisfy New York theatergoers -- Irish-American or otherwise. Organizations such as the Irish Theatre of America gave realistic depictions of rural Irish life. Americans -- especially Irish-Americans -- preferred rosier, less true-to-life portrayals of the Emerald Isle.

Desire More Than Reality

The Irish Theatre of America debuted on February 9, 1915 at the Central Opera House, co-directed by Padraic Colum and John P. Campbell. Colum had performed with the Irish National Theatre Society (which, in 1904, made its permanent home at the Abbey in Dublin) and wrote plays produced by the latter theater as well.[2] Campbell was a founding member of the Ulster Literary Theatre and arrived in the United States while on tour in December 1912. He soon made his mark as the director of the 1913 Irish Historic Pageant, a massive production held at the Sixty-Ninth Regiment Armory in New York City featuring ancient Celtic heroes and Gaelic costumes.[3]

The“Irish Theatre of America”sounded established, but the name reflected desire more so than reality. Colum hoped for the creation of a permanent Irish theater whose plays might help to“produce a national culture among the Irish people in America.”To be successful, he insisted, such a company would have to show works about the Irish-American experience by Irish-American playwrights. Colum sensed in particular that the Irish in the United States did not wish to see Irish peasants on stage.[4] The hostility Irish Americans had displayed in 1911 towards the Abbey touring production of The Playboy of the Western World surely informed this suspicion.[5]

One commentator in the Irish World explained that Colum’s vision would require Irish Americans to question their love of melodramas. Admired actors Chauncey Olcott and Andrew Mack, both of Irish descent, performed in such plays. Irish playwright Dion Boucicault’s melodramas were popular on both sides of the Atlantic, especially in the nineteenth century. Yet Boucicault’s plays and Olcott’s characters perpetuated the image of the cartoonish stage Irishman and sentimentalized the Irish and Ireland. Although problematic, Boucicault’s melodramas were at least an improvement upon earlier nineteenth-century depictions of the Irish as figures of ridicule.[6]

From its start, the Irish Theatre of America continued to offer realistic portrayals of Irish agrarian life as it sought a more permanent home. During its inaugural season in April 1915, organizers of the Neighborhood Playhouse on the Lower East Side invited the band of actors to put on Irish folk plays. The Playhouse, affiliated with the Henry Street Settlement, aimed to produce anti-commercial, experimental works and considered the Abbey an inspiration.[7]

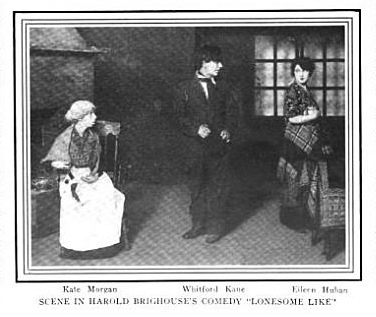

Kate Morgan, Whitford Kane, and Eileen Huban

Joined by actor Whitford Kane, Campbell stayed on as a director. Both men had performed with the Ulster Literary Theatre and had journeyed to the United States together while on tour. Kane, born in Larne, in what is now Northern Ireland, began his theatrical career in England. Yet he credited the Ulster company with teaching him that he did not have to pretend to sound English to land roles and felt a strong pull to the national theater movement.[8]

The Irish Theatre of America found success as well as resistance at the Neighborhood Playhouse. This was likely due not only to the group’s not staging sentimental fare, but also to its putting on peasant plays. One angry theatergoer disrupted a performance of the Red Turf, because he objected to the story about a husband in western Ireland whose wife encourages him to murder a neighbor. Kane later recalled that the man directed everyone in the audience to see what he deemed an authentic Irish story at the Lexington Opera House: “There, we were informed, we would see a play about the real Ireland everybody loved, not a sordid story of bickering farmers.”[9]

Kane took the man’s advice and found himself seated at a typical melodrama. “I knew,” he explained,“the whole Chauncey Olcott recipe. I knew the minstrel hero would be a rebel; I knew the daughter of the aristocrat would fall in love with him: I knew the father would discover the hero in disguise at a masked ball: and I knew that the aristocrat would order the arrest of ‘the damned rebel dog.’”[10]

In May 1915 the Irish Theatre of America moved uptown to the Bandbox Theatre and lost its Irish audience.[11] This meant fewer, if any, interruptions. It also defeated the purpose of impressing Irish-Americans.

Better opportunities for the actors and directors lay elsewhere. In early 1917, the Irish Theatre of America announced it would cease production until after the war in Europe.[12] Members of the company found work in Irish plays, but not those in the tradition of the Abbey.

In 1917, some of the group performed in a Broadway production set in Ireland called Grasshopper.

Co-written by Colum and starring Campbell, the play was relatively well received, but it was a compromise of artistic values. The first act was typical of Abbey productions: heavy on dialogue and lacking in high emotional intrigue.By the the end of act one, however, the play changed. “With no preliminary warning,” a Sun observer noted, “the spirit of the stage Irishman of Dion Boucicault suddenly stalked during the second act into the drama.”[13] The Grasshopper did reflect some of the characteristics and traditions of the Irish national theater movement, and cast members Lilian Jago and Máire Digges had professional ties to the Abbey.[14] But the production could not sustain Abbey standards and achieve commercial success.

Dark Rosaleen, another Broadway show linked to members of the Irish Theatre of America, took compromise even further. Produced in 1919 and co-written by Kane, the play demonstrated his willingness to pander, the plot centering on a romance and a horse race in Ireland. Writing for the New-York Tribune, Heywood Broun described it as “in the manner of the old-fashioned drama which was popularized in this country by Dion Boucicault” and “a sentimental portrait in which the son of Erin is held up as drunken, irresponsible, and guilt-hearted.”[15]

Irish-Americans loved it.

“Our public,” Kane remarked, “was comprised of red-faced dowdy ould country women who seemed to have come to Forty-Fourth Street for the first time in their lives.”[16]

Dark Rosaleen made Galway-born actress Eileen Huban a Broadway star, despite her objections. Huban had met Campbell as a teenager while performing in the 1913 Irish Historic Pageant. Impressed, Campbell and Kane invited her to join the Irish Theatre of America. She went on to star in Grasshopper. Huban repeatedly refused Kane’s efforts to get her to take on the lead role of Moya McKillop in Dark Rosaleen; the material, it seems even more stage Irish than Grasshopper, offended her.But she eventually had no choice. Famed Broadway producer David Belasco purchased the play and Huban was under contract to him.[17]

The play’s success apparently inspired a new effort to establish an Irish national theater -- the Celtic Players -- but it, too, grappled with how to stay afloat financially. Formed in April 1920, the troupe included Eileen Curran and Helen Evily of the Irish Theatre of America.[18] Members Lilian Jago, Máire Diggs, and P. J. Kelly had roots in the Abbey.[19] The Celtic Players banked on the name recognition of Dark Rosaleen cast members Curran, Kelly, and Bina Flynn.[20]

Eileen Huban and David Belasco

Deborah Bierne, a manager of traveling concert and opera companies,organized the group and worked to fundraise to establish a permanent Irish theater. In so doing, she also criticized others -- that is, the Irish Theatre of America -- who had organized as a body of actors before securing a playhouse. Bierne did the opposite.[21] She took seriously the goal of making a profit.

New York Tribune, June 11, 1920

Yet her commitments to Abbey-style drama are suspect. Born in Florida to Irish immigrants, Bierne was at least of Irish descent. But within a week of the launch of the Irish Theatre of America, she helped found the American Irish Players Company, a group which announced its intentions to offer an alternative to Abbey-type theatricals it claimed put “Ireland’s moral reputation in jeopardy.”[22]

Behind the scenes, Bierne also proved a divisive figure. Publicly, she embraced the Celtic Players’ larger goals and their efforts to put on Abbey-style plays. Backstage, she tried to silence her squabbling actors by telling them that their actions threatened the establishment of an Irish national theater.[23]

Disputes over money and control led the Celtic Players to split in two within months of forming. The company was a co-operative to the extent that the actors earned equal amounts and their pay was relative to ticket sales. Doing well at the box office, in June 1920, Bierne announced that her players would move uptown near Times Square to the Thirty-ninth Street Theatre.[24] Some of the cast resisted. They wanted to remain downtown and become fully co-operative, meaning that the performers, not management, be in charge of selecting plays and scheduling rehearsals. Paul Hayes, Henry O’Neill, Eileen Curran, Bina Flynn, Angela McCahill, Clement O’Loghlen, and others retained the name Celtic Players and established themselves under Whitford Kane’s direction at the Bramhall Theatre on East Twenty-Seventh Street.[25]

Pressures to realize profits were far greater uptown, and, as the Irish Theatre of America had learned, folk plays did not do well there. Those who stayed downtown with Kane were not wrong to suspect that moving to the Thirty-ninth Street Theatre might not be worth the risk. Nevertheless, several of the company, including Helen Evily and P. J. Kelly, stuck with Bierne and her commercial venture, rechristening themselves the Irish Players.[26]

New York Tribune, June 20, 1920

With an eye for drawing audiences, Bierne acquired the rights for the Irish Players to stage the first American production of George Bernard Shaw’s O’Flaherty, V.C. The one-act play, slated to be performed at the Abbey in Dublin until military censorship rendered that impossible, tackled the controversial topic of conscription through the lens of an Irish soldier in the British army.[27] Shaw’s response to Bierne’s request to produce the play makes clear that Bierne thought it would bring the Irish Players “recognition.”[28]

Mollie Carroll

Hiring actress Mollie Carroll also served as a means to drumming up potential ticket sales. Known for her work in Dark Rosaleen and other plays, Carroll drew national attention in April 1920 by flying a plane over Washington, D.C. and showering the city with leaflets demanding recognition of the Irish Republic.[29] If any actress could attract ticket-buyers, especially Irish-American ones, to modern Irish drama in the summer of 1920, it was her.

Despite their differences, the Celtic and the Irish Players both intended to establish Irish national theaters.Moreover,at the same time both staged The Rising of the Moon, written by Abbey co-founder Lady Augusta Gregory. Theater critics did not take kindly to the duplicate productions.[30]

The Irish Players’scheduled eight-week run closed after only a week because of insufficient ticket sales. Bierne kept trying, incorporating the National Irish Theatre Company with plans to unite the Celtic and Irish Players on a commercial basis. In 1921, “Deborah Bierne’s Irish Players,” as they were called, continued those efforts. But that endeavor also failed. By December 1922, Actors’ Equity was out looking for Bierne to settle claims against her for unpaid wages.[31]

Kane, on the other hand, came to accept that New Yorkers did not want to see plays about Irish peasant life.[32] He soon tried to change his group’s focus to Shakespeare, arguing that Elizabethan drama was, in fact, part of a Gaelic theatrical tradition rather than an English one, and that they could put on the Scottish play Macbeth because it was “Celtic.”[33] Dixie Hines, Kane’s own theatrical representative, dismissed the plan as “O’Shakespeare.”[34]

The goal of establishing a permanent Irish national theater in New York proved insurmountable in the early 1920s, but these thespians’ efforts were not in vain. Some, of course, moved on. Henry O’Neill, notably, found success in Hollywood films.[35] For others, the work to start an Irish theater proved to be one element in a lifetime commitment to promoting Irish culture in the five boroughs. Eileen Curran, for example, championed Irish music and folklore on the radio, gave concerts, and, in 1935, directed a feis, a festival celebrating Gaelic arts, dance, and music, attended by some 2,000 people.[36]

More immediately, the push for an Irish national theater in New York City proved important to local Irish republican activism. Several of the actors and actresses belonged to the Irish Progressive League and like organizations. Peter Golden, who had performed with Irish Theatre of America in 1915, led the league as its general secretary. Mollie Carroll assisted the league from its start 1917. Actor Emmet O’Reilly was a founding member of both the league and the drama company. Kate Morgan, also of the Irish Theatre of America,was active in Citizens of the Irish Republic.[37]

Irish republican groups worked to generate publicity for the sake of encouraging Americans to support U.S. recognition of the Irish Republic. The name recognition of theatrical members served such efforts. The Irish Theatre of America, the Celtic Players, and the Irish Players may have struggled to find their audiences, but reporters and photographers were happy to cover Irish republican protests -- if only to give the public a glimpse into the lives of attractive actresses such as Curran and Carroll who, in turn, were very comfortable being in the spotlight.[38]

Catherine M. Burns holds a Ph.D. in U.S. History from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her work has appeared in New Hibernia Review and The Irish in the Atlantic World (University of South Carolina Press, 2010). In 2009, the New York Irish History Roundtable awarded her the John J. O’Connor Graduate Scholarship for her work on the Irish in New York City.

[1] Mary Trotter, Ireland’s National Theaters: Political Performance and the Origins of the Irish Dramatic Movement (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2001), especially pages xii-xiv, 11-13; Eugene McNulty, The Ulster Literary Theatre and the Northern Revival (Cork, Ireland: Cork University Press, 2008), 3-6, 9-11, 74-76, 116-117. Trotter focuses on Dublin. Also useful on the cultural orientation of the Ulster Literary Theatre is Karen Vandevelde, “An Open National Identity: Rutherford Mayne, Gerald MacNamara, and the Plays of the Ulster Literary Theatre,” Éire-Ireland 39, no. 1 and 2 (Spring/Summer 2004): 36-58.

[2]New York Times, 10 February 1915; Trotter, Ireland’s National Theatres, 107, 120.

[3] Paul Larmour, “John Campbell (1883-1962): An Artist of the Irish Revival,” Irish Arts Review Yearbook 14 (1998): 66-67; “Irish Historic Pageant” (program), New York Public Library, Maloney Collection of Irish Historical Papers, Box 11, Folder 162; Anna Throop Craig, Book of the Irish Historic Pageant; Episodes from the Irish Pageant Series “An Dhord Fhiann” (New York, 1913), 4-5.

[4] New York Times, 14 February 1915.

[5] For a detailed look at responses to the play in various cities, see M. Alison Kibler, Censoring Racial Ridicule: Irish, Jewish, and African American Struggles over Race and Representation, 1890-1930 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015), 101-110.

[6] Irish World and American Industrial Liberator (IWAIL), 6 February 1915; William H. A. Williams, ’Twas Only an Irishman’s Dream: The Image of Ireland and the Irish in American Popular Song Lyrics, 1800-1920 (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1996), 98-100, 214.

[7] New York Times, 15 April 1915; John P. Harrington, The Life of the Neighborhood Playhouse on Grand Street (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2007), 52, 63.

[8] Whitford Kane, Are We All Met? (London: Elkin Mathews and Marrot, 1931), 110, 117, 175.

[9] Kane, Are We All, 176.

[10] Kane, Are We All, 177.

[11] Kane, Are We All, 178-179.

[12]The New York Clipper, 10 January 1917.

[13]The Sun (New York), 9 April 1917.

[14] Robert Welch, The Abbey Theatre, 1899-1999: Form and Pressure (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 31, 63.

[15] Heywood Broun, “Old Style Drama Still Popular Here,” New York Tribune, 27 April 1919.

[16] Kane, Are We All, 202.

[17]The Sun (New York), 9 April 1917, 18 November 1917; Kane, Are We All, 195-198.

[18]The Sun and New York Herald, 29 April 1920; “Neighborhood Playhouse,” April 1915, National Library of Ireland (NLI), Peter Golden Papers (PGP), Ms. 13141, Folder 1-C; New-York Tribune, 9 July 1916.

[19]New York Times, 1 June 1919.

[20] John Corbin, “A Dark Irish Horse,” New York Times, 23 April 1919; The Sun and New York Herald, 1 May 1920; New-York Tribune, 13 June 1920.

[21] IWAIL, 27 February 1915; New-York Tribune, 30 May 1920.

[22] New-York Tribune, 30 May 1920; IWAIL, 27 February 1915. Quotation from New-York Tribune, 17 February 1915.

[23] New-York Tribune, 30 May 1920.

[24] The Sun and New York Herald, 24 June 1920; New York Times, 15 June 1920;

[25] The Sun and New York Herald, 24 June 1920; Call (New York), 21 June 1920, 4; The New York Clipper, 30 June 1920; Call (New York), 27 June 1920. The 1919 Actors’ Equity strike likely also influenced the Celtic Players’ split.

[26] The New York Clipper, 30 June 1920.

[27] The Sun and New York Herald, 24 June 1920; Joan FitzPatrick Dean, Riot and Great Anger: Stage Censorship in Twentieth-Century Ireland (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2010), 112; Terry Phillips, “Shaw, Ireland, and World War I: O’Flaherty, V.C., an Unlikely Recruiting Play,” Shaw 30 (2010): 133-146.

[28] Washington Times, 4 June 1920.

[29] The New York Clipper, 7 July 1920; New York Times, 23 April 1919, 3 April 1920; Irish Press (Philadelphia), 10 April 1920; Washington Herald, 7 April 1920.

[30] Call (New York), 27 June 1920; The Sun and New York Herald, 27 June 1920; Theatre Magazine (September 1920): 108.

[31] New-York Tribune, 3 July 1920; The New York Clipper, 6 October 1920; New-York Tribune, 6 February 1921; The New York Clipper, 20 December 1922.

[32] Kane, Are We All, 217.

[33] Call (New York), 12 July 1920. Quotation in New-York Tribune, 6 July 1920.

[34] Kane, Are We All, 140; Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), 18 July 1920.

[35] “Henry O’Neill,” IMDb, accessed March 3, 2016, http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0642180/.

[36] New York Times, 29 October 1933, 23 August 1935; “Cuirim Cheoil Annual Concert” (program), 11 April 1937, New York University, Tamiment Library, Gaelic Society Papers, Box 1, Folder 5; New York Times, 25 August 1935.

[37] “Neighborhood Playhouse” (handbill), April 1915, NLI, PGP, Ms. 13141, Folder 1-C; Minutes of the Irish Progressive League Meetings, 30 November 1917, NLI, PGP, Ms. 13141, Folder 2; IWAIL, 20 October 1917;New York Times, 22 June 1920;Irish Press (Philadelphia), 28 August 1920.

[38] The Sun and the New York Herald, 28 August 1920; New York Times, 3 April 1920, New York Tribune, 6 April 1920; Boston Globe, 6 April 1920.