From Pond to Park: The History of the Collect Pond Site

By Robert Pigott

As a bit of greenery opposite the Criminal Court on Centre Street has replaced an unsightly municipal parking lot, the name given this new park -– Collect Pond Park -- evokes 400 years of New York City history. The soggy origins of the block containing the new park pre-date the 17th century encounter of the Dutch settlers of New Amsterdam and the Native Americans who inhabited the woods, fields, streams and ponds that were pre-colonial Manhattan.

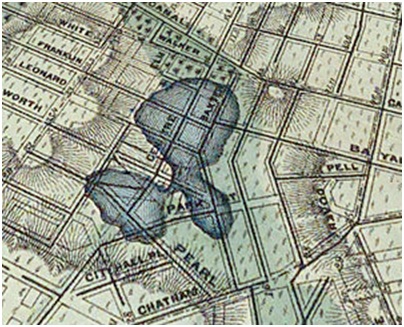

At that time, this block, bounded by Centre, Leonard, Lafayette and Franklin Streets, and the surrounding area were the site of Collect Pond, a five-acre, 60-foot deep pond fed by an underground stream. As New York City, in its early years confined below Wall Street, grew uptown, its more noxious industries, such as slaughterhouses and tanneries, were exiled north of the City to the banks of the Collect Pond. By 1802, the once glistening Collect Pond had become polluted, and the Common Council voted that it be filled in with soil from the neighboring Bunker Hill (thereby leveling what had been a namesake of the more famous Boston hill).

The elimination of Collect Pond was completed by 1813, at the very time that poorer immigrants were beginning to arrive in New York City in greater numbers. Many settled in this still somewhat swampy area, which took its name, Five Points, from the intersection of five streets (Mulberry, Anthony [now Worth], Cross [now Park], Orange [now Baxter] and Little Water [which no longer exists]) at its center.

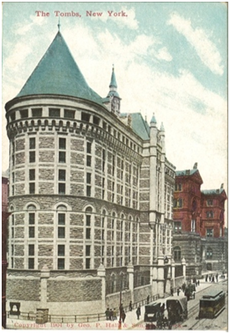

Five Points became the most notorious neighborhood in New York City. Its ramshackle, overcrowded, sinking buildings were a breeding ground for crime. But, at the westernmost edge of the Five Points neighborhood, the City erected, on the block of the current Collect Pond Park, a bulwark against this criminal underworld.Built in 1838 as The Halls of Justice to house the Court of Special Sessions and the Police Court, “The Tombs” gained greater fame as a prison. Its Egyptian Revival style gave rise to the building’s “Tombs” nickname.

The Tombs was visited by Charles Dickens in 1842, and it was the final place of confinement of Herman Melville’s obstinate, laconic Bartleby the Scrivener. The building was replaced on the same site in 1900 by a second Tombs prison. Both Tombs prisons were plagued by the site’s watery origins. Because of the underground stream that had once fed Collect Pond, both buildings were dank and structurally unsound.

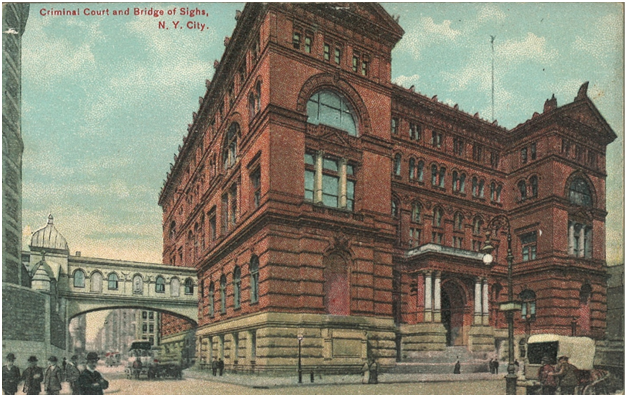

In 1893, one block to the north of The Tombs, the City constructed the Criminal Courts Building, which was the principal criminal courthouse in New York County until the construction in 1939 of the current Criminal Courts Building at 100 Centre Street. A “Bridge of Sighs” over Franklin Street connected the Criminal Courts Building to The Tombs to facilitate the transportation of prisoners from their cells to the courtrooms. In 1914, the Criminal Courts Criminal Courts Building, connected to the Collect Pond Park block by the “Bridge of Sighs” Building was the site of the manslaughter trial of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory owners, which resulted in their acquittal. Both the Criminal Courts Building and The Tombs were razed in 1946, with the construction of the current Criminal Courts Building directly across Centre Street.

The Second Tombs (left) on the future site of Collect Pond Park, and the Criminal Courts Building (right) [Dover Publishing]

The former parking lot on the site of Collect Pond Park in the 1970’s,

with the current Civil Court Courthouse at 111 Centre Street one block uptown.

Today, The Tombs consists of two buildings on the opposite side of Centre Street: one at the north end of the 100 Centre Street Criminal Courts Building and the other just across White Street, connected by a bridge. Although the “Tombs” nickname has endured, the “Bridge of Sighs” sobriquet appears not to have (except among a few court system old-timers).

The finishing touches on Collect Pond Park are just about completed. The chain link fence that surrounded it for several years has come down. Although the park benches and squares of green now provide some relief to the court personnel and others who frequent the park, it is a far cry from the pristine beauty of the colonial-era Collect Pond. But it is a decided improvement over the noxious slaughterhouses, forbidding jail and asphalt parking lot that successively occupied this block.

Robert Pigott, a lawyer, adapted this article from his New York’s Legal Landmarks: A Guide to Legal Edifices, Institutions, Lore, History and Curiosities on the City’s Streets. Reprinted with permission of The Broadsheet.

![The Second Tombs (left) on the future site of Collect Pond Park, and the Criminal Courts Building (right) [Dover Publishing]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d23a00f53f6300001f811bb/1568212303823-Z19T88ZQ1HHVQ3K2RZDM/3443072.png)