“God is Forgotten, and the Soldier Slighted”: New York City’s Golden Hill and Nassau Street Riots and the Affective Rhetorics of Crowd Violence

By Russell L. Weber

Winter’s chill clutched New York City the morning of January 19, 1770.[1] Such unwelcoming weather might have persuaded some New Yorkers to remain indoors, fill their stoves with more firewood, and delay their trip to the market. The soldiers of Britain’s 16th Regiment of Foot, however, ignored January’s harsh bite. As these regulars made the half-mile walk from their barracks to Fly Market, their boiling blood kept them warm.[2] Several days prior, a New York City Son of Liberty had slandered King George III’s soldiers, arguing that Parliament had stationed them within the city to “enslave” its civilian populace and that the New York Assembly was squandering the colony’s tax revenue to provide food and shelter for the 16th Regiment’s “Whores and Bastards.”[3]

Infuriated by these attacks against both their military honor and their defenseless families, the 16th Regiment authored a rebuttal, entitled God and a Soldier, rebuking these accusations. The broadside’s opening poem provides the clearest representation of the anger and sadness that these soldiers felt while enduring such cruelty from fellow Britons: “God and a Soldier all Men doth adore,/In Time of War, and not before:/When the War is over, and all Things righted,/God is forgotten, and the Soldier slighted.”[4] Thousands of miles from home, earning barely enough to support themselves and their families, and constantly attacked by the very civilians whom king and Parliament had ordered them to protect, the 16th Regiment hoped that their humble petition would convince New Yorkers to treat them with the respect they merited as soldiers, if not the kindness they deserved as fellow Britons. Abandonment, sorrow, and rage all swirled together as the 16th Regiment distributed copies of God and a Soldier to those shopping at Fly Market the morning of January 19. The emotional pleas of the 16th Regiment fell upon frozen hearts; the circulation of God and a Soldier inadvertently ignited the Golden Hill and Nassau Street riots, two of the most profound episodes of anti-soldier popular violence to occur during British America’s Quartering Crisis.[5]

John Singleton Copley, “General Thomas Gage,” 1768. Yale University Art Gallery, Paul Mellon Collection

Britain’s victory in the Seven Years’ War secured its status as the dominant imperial power east of the Mississippi River. To protect British Americans from both French invasion and Indigenous raids, Parliament stationed British regulars throughout its colonies, with the explicit expectation that colonial legislatures would provide both provisions and lodgings to these soldiers. The Commander of Britain’s forces in North America, General Thomas Gage, despised his subordination to the mercurial whims of these legislatures and petitioned Parliament to grant him absolute power for “maintain[ing] order” in British America.[6] The subsequent American Mutiny Act of 1765, popularly known in British America as the Quartering Act, minimally increased Gage‘s economic authority, as it permitted him to requisition supplies and quarter soldiers in public houses, but prohibited him from billeting his soldiers in any private home.[7]

Despite its profound limitations, British Americans condemned the Quartering Act as another tool of Parliamentary oppression.[8] Resistance to the Quartering Act was particularly acute in New York City, which served as central command for Britain’s North American military forces. General Gage’s attempt to implement the Quartering Act in late-October 1765, amidst the fury of New York City’s Stamp Act riots, ended disastrously: the colonial assembly refused to allocate funds for his soldiers’ provisions and the city’s mob burnt him in effigy.[9] The Stamp Act’s subsequent repeal in March 1766, however, did nothing to ameliorate New Yorkers’ fears of the tyrannical potential of Parliament’s peacetime standing army. As New York merchant John Watts remarked, British Americans would “rather part with their money, though rather unconstitutionally” than suffer a “parcel of military masters put… [into] a bed [with] their wives and daughters.”[10]

By mid-July 1766, New York’s Assembly still “refuse[d] compl[iance]” with the Quartering Act and, by mid-August, New York City’s Sons of Liberty demanded that all “market people should not sell any provisions to any of the officers or Soldiers” quartered within the city.[11] The Assembly’s fiscal disregard for Gage’s soldiers only exacerbated hostilities, as New York City’s dockworkers “suffer[ed]” competition from moonlighting soldiers willing to work for substantially less pay.[12] In London, New York’s neglect of British regulars not only “raised a spirit in Parliament which [Britons] ha[d] not seen before,” but also “indicated a throwing off [of colonial] dependence on the Mother Country.”[13] Tensions further escalated in 1767, when Massachusetts’s House of Representatives proclaimed solidarity with New York and “flatly refused” to support any British soldier quartered within the colony.[14]

New York’s blatant disrespect of imperial authority encouraged Parliament to pass An Act for Restraining and Prohibiting the Governor, Council, and House of Representatives, of the Province of New York (1767). Implemented on October 1, 1767, the Restraining Act prevented Governor Henry Moore from “consent[ing] to any statute until the assembly complied with the Quartering Act,” thus nullifying New York’s legislative power.[15] Parliament’s aggressive punishment of New York, however, only evoked sympathy throughout British America. Massachusetts’s House of Representatives argued that this unjust law both “depriv[ed] the people of a fundamental right of the constitution” — representation — and suggested that Parliament now threatened all of British America with “political death and annihilation.”[16] Even Virginia’s political elite feared that the suspension of New York’s legislature hung, “like a flaming sword, over [their] heads and require[d], by all means, to be removed.”[17]

After enduring the Restraining Act for two years, New York’s Assembly finally appropriated £2,000 to support British regulars within the colony.[18] Resentment quickly spread throughout New York City, fomented by Son of Liberty Alexander McDougall’s broadside To the Betrayed Inhabitants of the City and Colony of New-York. [19] Published on December 16, 1769, To the Betrayed Inhabitants begins with an uncontroversial premise: that if the “Minions of Tyranny and Despotism” committed “their malevolent and corrupt Hearts… to enslave a free People,” then the civic representatives of that free people must resist such corruption.[20] Tragically, New York’s Assembly had abandoned this responsibility by submitting to the “tyrannical Conduct” of Parliament and using the colony’s tax revenue to feed, clothe, and quarter those “Troops kept here, not to protect, but to enslave.“[21] New Yorkers, McDougall argued, not only must fear such tyrannical encroachments against their colony, but also must be enraged at the Assembly’s willingness to sacrifice liberty for power.

McDougall then implored the readers of To the Betrayed Inhabitants to attend a meeting on December 18th, at which the attendees would determine how best to obstruct the “Design of Tyrants,” noting that they would assume absence as implicit consent “to what may be done.”[22] Through this rhetorically manipulative claim, McDougall created a political double-jeopardy for those who supported Parliament’s Quartering Act: if they attend the meeting, it would imply their support for the Sons of Liberty, and if they abstained, McDougall would assume their silent consent. “I am confident,” McDougall declared, that this anti-quartering meeting would “spirit the Friends of [their] Cause” and encourage fraternal affection among the inhabitants of New York City.[23] By stoking fear, rage, and fraternal love, McDougall’s To the Betrayed Inhabitants provides an undisputable, impassioned “call-to-arms,” imploring the inhabitants of New York City to be prepared to defend their rights as British subjects.

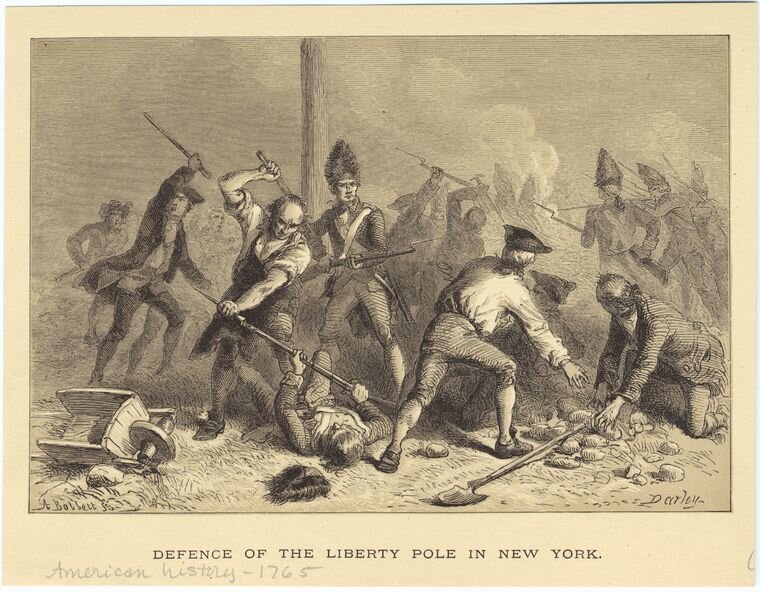

Felix Octavius Carr Darley and Albert Bobbett, “Defence of the Liberty Pole in New York,” 1879. New York Public Library, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints, and Photographs.

No substantive record exists of the December 18th meeting, yet it unquestionably escalated tensions within New York City. In the weeks that followed, the city’s populace became more aggressive not only in their opposition to the Assembly’s appropriations bill, but also in their harassment of British soldiers. As civilian hostility rapidly intensified, so too did the British soldiers own violent, enraged retaliations.[24] Unable to endure such abuse any longer, several soldiers of the 16th regiment “attempted to blow [up]” New York City’s Liberty Pole the evening of January 13, 1770.[25] Patrons of De La Mountayne’s tavern heard the failed explosion and ran outside to confront the soldiers, who fixed bayonets and then chased the civilians back into the tavern, “destroyed all [its] Front Windows,” and one zealous soldier “made a Thrust with his Bayonet” at a patron, who luckily suffered only a minor gash to his forehead.[26]

The 16th Regiment’s assault on New York City’s Liberty Pole further exacerbated political tensions, as it drew upon the city’s contentious history of crowd-soldier violence. New York City’s radicals first debuted their Liberty Pole in late-May 1766 to commemorate the repeal of the Stamp Act.[27] Intentionally provocative, radicals chose to erect the Liberty Pole in New York City’s Commons, “a liminal zone, neither wholly civilian nor martial” due to its proximity to the regulars’ barracks.[28] When New York’s Assembly first signaled their opposition to the Quartering Act, enraged British soldiers razed the Liberty Pole on August 10, 1766.[29] The next day, a group of two to three thousand civilians, led by Son of Liberty Isaac Sears, demanded an apology from the soldiers, which quickly devolved into a brawl.[30] Undeterred, the Sons of Liberty erected another Liberty Pole and intensified their daily insult of the soldiers.[31] Skirmishes continued for seven-months, culminating on March 18, 1767, the first anniversary of the Stamp Act’s repeal, when British soldiers yet again demolished the Liberty Pole, only for the Sons of Liberty to raise another and furnish it with guards to prevent further molestation.[32] By March 22nd, the soldiers had abandoned their siege on New York City’s Liberty Pole.[33]

The 16th Regiment’s decision to desecrate New York City’s Liberty Pole on January 13, 1770 and reignite this violent feud demonstrates the tremendous abuse that they suffered in the wake of McDougall’s broadside. Following a second attack on the Liberty Pole on January 15th, another Son of Liberty, employing the pseudonym Brutus, published a broadside entitled Whoever Seriously Considers the Impoverished State of this City.[34] Echoing McDougall’s impassioned rhetoric, Brutus argued that the British soldiers stationed within the city were “not kept here to protect, but enslave [them].”[35] Kindling the ever-present fear of civic enslavement, Brutus implored his readers to refuse to hire British soldiers, as they deserved neither “the Employment of the Poor” nor colonial tax revenue to support their “Whores and Bastards.”[36] For Brutus, as for McDougall, fear of political enslavement and rage at fiscal misappropriation were essential rhetorical tools to encourage attendance at another anti-quartering meeting, which was held on January 17th.

Distraught at such relentless abuse, the soldiers of the 16th Regiment finally engaged in New York’s impassioned print discourse. The morning of January 19th, the 16th Regiment distributed God and a Soldier, in which they argued that they were victims of a malicious and unjust political vendetta.[37] The “real enemies” of New York, the soldier argued, were the Sons of Liberty, who incited this “uncommon and riottous disturbance” by demonizing King George III’s loyal soldiers in such “a heinous light.”[38] Condemning Brutus’s “seditious libel,” the soldiers assured the populace that they “will stand in defence of the rights and privileges due to a soldier, and no farther.”[39] Finally, God and a Soldier begged that “every honest heart support the soldiers’ wives and children,” whom the Sons of Liberty have “maliciously, falsely, and audaciously” labeled “whores and bastards.”[40] Emphasizing both their selfless devotion to Britain and their love for their innocent families, the 16th Regiment hoped to humanize themselves and prove that they were not a tyrannical threat to New York City.

J. Evers, “Fly Market from the corner Front Street and Maiden Lane, N.Y. 1816,” 1857. South Street Seaport Museum, Drawings and Prints Collection.

While potentially persuasive, God and a Soldier never reached its intended audience. Sons of Liberty Isaac Sears and Walter Quackenbos witnessed several soldiers distributing God and a Soldier at Fly Market and, after quickly reading a posted copy, seized one of the soldiers and demanded to know “what business he had to put up libel against the inhabitants” of New York.[41] Witnessing this unprovoked assault, another soldier tried to fix his bayonet, but Sears struck him unconscious.[42] As the remaining soldiers fled, Sears and Quackenbos brought the two incapacitated soldiers before Mayor Whitehead Hicks and accused them of libel.[43] Minutes later, a crowd of civilians, armed with sleighs and rungs, and a group of approximately twenty soldiers, armed with “Cutlasses and Bayonets,” descended upon the Mayor’s home.[44] To avoid bloodshed, Hicks ordered the soldiers to return to barracks, yet the crowd took it upon themselves to serve as an escort, fearful that the soldiers would “offer violence to some of the citizens” they passed.[45]

Bernard Ratzer, This Plan of the City of New York, 1769. Library of Congress. 16th Regiment’s Barracks [Red Dot]; Fly-Market [Blue Dot]; Golden Hill Riot [Green Dot]

After turning onto Golden Hill Street, reinforcements from the 16th Regiment arrived, which then “inspired” the soldiers “to reinsult the Magistrates, and exasperate the Inhabitants.”[46] During this exchange, a man dressed in “Silk Stockings, and neat Buckskin Breaches,” whom the New York Gazette reported to be a “Officer in Disguise,” ordered the soldiers to fix bayonets, who then assaulted the civilians “with great violence, cutting and slashing.”[47] The aggravated soldiers even attacked innocent bystanders, such as a Quaker, a young woman, and a boy going to Fly Market “for sugar.”[48] Eventually, the city’s magistrates and Captain Richardson ended the quarrel.[49] Another riot, however, occurred the following day on Nassau Street between fifteen soldiers and a few civilian sailors.[50] While the sailors likely initiated the conflict, the 16th Regiment attacked them with “the greatest rage and would have killed them” had civic leaders and military officers not ended the conflict.[51]

Miraculously, no soldiers or civilians died in the Golden Hill and Nassau Street riots. To avoid further conflict, however, General Gage ordered all soldiers to be confined to barracks.[52] While Gage immediately quelled the physical violence, animosity and terror continued to fester. On January 30, five Sons of Liberty, including Isaac Sears and Alexander McDougall, jeopardized the uneasy political détente by petitioning New York’s City Council to “erect another LIBERTY POLE, as a Memorial of the Repeal of the Stamp Act.”[53] To protect the fragile peace, the City Council rejected the petition. Undeterred, the Sons of Liberty immediately purchased a small piece of land, closer to the military barracks than the city’s Commons.[54] The New York Journal reported that several thousand inhabitants of New York City attended the Liberty Pole’s dedication on February 6 and, while many soldiers of the 16th Regiment were present, they “neither gave nor received any Affront.”[55]

Although it may seem as though the Golden Hill and Nassau Street riots ended with a whimper, their true significance emerges from the affective, political influence they had on British America, specifically Boston. The afternoon of February 22, 1770, “three days after” Boston learned of New York City’s Golden Hill riot, its own Sons of Liberty held a solidarity protest, condemning the 16th Regiment’s unjustified hostilities.[56] Amidst the chaos, a crowd of adult men and schoolboys descended upon the shop of Theophilus Lillie.[57] As the “the rage of the people increased,” Ebenezer Richardson, a Parliamentary apologist and friend of Lillie, “fired into the crowd,” wounding nineteen-year old Samuel Gore and killing eleven-year-old Christopher Sneider.[58] For Boston’s radicals, such as Samuel Adams, the murder of young Sneider proved to be an incendiary flash-point, through which they fomented rage, terror, and ultimately popular violence against both British soldiers and Parliamentary loyalists within their city. New York’s Golden Hill and Nassau Street riots, therefore, must be not only understood as a crucial moment of political violence during British America’s Quartering Crisis, but also reinterpreted as a fundamental catalyst for the shocking massacre that occurred in Boston the night of March 5, 1770.

Russell L. Weber is a PhD Candidate at the University of California, Berkeley, studying the history of emotions and political culture in the early-modern Atlantic world. His dissertation, "American Feeling," explores how British America's radical elite employed emotions, print media, and popular violence to fabricate a new patriotic ethos and national identity for the fledgling United States of America.

[1] Frank Freeman, Freeman’s New-York Almanack for the Year of our Lord, 1770 (New York: John Holt, 1769), 9; American Antiquarian Society.

[2] “New York City, c. 1770” in Atlas of Early American History: The Revolutionary Era, 1760-1790, eds. Lester J. Cappon, et al. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1976), 10.

[3] Brutus, Who Seriously Considers the Impoverished State of this City (New York, 1770); Library Company of Philadelphia.

[4] Soldiers of the 16th Regiment, God and a Soldier (New York, 1770); New York Public Library.

[5] For narratives of the Golden Hill and Nassau Street Riots, see Paul A. Gilje, The Road to Mobocracy: Popular Disorder in New York City, 1763-1834 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1987), 54-60, John Gilbery McCurdy, Quarters: The Accommodation of the British Army and the Coming of the American Revolution (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2019), 193-196, and Joseph S. Tiedemann, Reluctant Revolutionaries: New York City and the Road to Independence, 1763-1776 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1997), 148-150. For the most extensive analysis these riots, see Lee Reese Boyer, The Golden Hill and Nassau Street Riots (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame, Diss., 1972), 124-162

[6] Fred Anderson, Crucible of War: The Seven Years’ War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754-1766 (New York: Vintage Books, 2000), 648-649.

[7] An Act to Amend and Render more Effectual, in his Majesty’s Dominions in America, An act Passed in this Present session of Parliament, intituled, An act for Punishing Mutiny and Desertion, and for the Better Payment of the Army and their Quarters (Boston: Draper and Green and Russell, 1765) 281-282; American Antiquarian Society; McCurdy, Quarters, 3.

[8] Thomas Gage to Henry Seymour Conway, December 21, 1765 in The Correspondence of General Thomas Gage with the Secretaries of State, 1763-1775, edited by Clarence Edwin Carter. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1931, 1:77; Anderson, Crucible of War, 696, 720.

[9] New York Gazette, or Weekly Post-Boy, December 23, 1765; John Montresor, The Montresor Journals, edited by G.D Scull (New York: New York Historical Society Collections, 1881), 344; McCurdy, Quarters, 112.

[10] John Watts to James Napier, June 1, 1765, in The Letter Books of John Watts, Merchant and Councillor of New York, January 1, 1762-December 1765 (New York: New York Historical Society, 1928), 354-355; McCurdy, Quarters, 100.

[11] John Montresor, The Montresor Journals, 373, 383.

[12] Ibid, 346.

[13] Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon), July 2, 1767; Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon), May 7, 1767.

[14] Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon), May 21, 1767, August 6, 1767.

[15] An Act for Restraining and Prohibiting the Governor, Council, and House of Representatives, of the Province of New York (London: Mark Baskett, 1767), New York Historical Society; Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon), November 5, 1767; Daniel J. Hulsebosch, Constituting Empire: New York and the Transformation of Constitutionalism in the Atlantic World, 1664-1830 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005), 140.

[16] Massachusetts’s House of Representatives to Dennis de Berdt, January 12, 1768 in The True Sentiments of America: Contain’d in a Collection of Letters sent from the House of Representatives of the Province of Massachusetts Bay to Several Persons of High Rank in this Kingdom (London: J. Almon, 1768), 75-76; Massachusetts Historical Society

[17] RHL to ------(in London), March 27, 1768, in The Letters of Richard Henry Lee, edited by James Curtis Ballagh. (New York: Macmillan Company, 1911), 1:27.

[18] McCurdy, Quarters, 193.

[19] Alexander McDougall, To the Betrayed Inhabitants of the City and Colony of New-York. (New York, 1769); New York Public Library. Even though Massachusetts and Virginia did not participate in out-of-doors political action directly against the Quartering Act, their regional print media circulated excerpts of McDougall’s broadside, likely to encourage, or project an image of, colonial solidarity; see Boston Gazette, January 8, 1770; Virginia Gazette, February 22, 1770. Gilje, Road to Mobocracy, 55.

[20] McDougall, To the Betrayed Inhabitants; Tiedeman, Reluctant Revolutionaries, 143.

[21] McDougall, To the Betrayed Inhabitants.

[22] McDougall, To the Betrayed Inhabitants.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Tiedemann, Reluctant Revolutionaries, 147.

[25] New York Gazette, or Weekly Post- Boy, January 15, 1770, February 5, 1770; Boston Gazette, February 19, 1770; New York Journal, March 1, 1770.

[26] New York Gazette, or Weekly Post- Boy, January 15, 1770, February 5, 1770; Boston Gazette, February 19, 1770; New York Journal, March 1, 1770.

[27] John Montresor, May 20-21, 1766, The Montresor Journals, 367-368.

[28] Gilje, Road to Mobocracy, 53-54; McCurdy, Quarters, 169.

[29] John Lamb, Memoir of the Life and Times of General John Lamb, ed. Isaac Q. Leake (New York: De Capo Press, 1971), 32-33; hereafter cited as Lamb Memoir; Montresor, Montresor Journals, 382-383; New York Gazette, or Weekly Post-Boy, August 21, 1766.

[30] John Lamb, Lamb Memoirs, 32-33; John Montresor, Montresor Journals, 382-383; New York Gazette, or Weekly Post-Boy, August 21, 1766.

[31] Ibid; Gilje, Road to Mobocracy, 54.

[32] Lamb, Lamb Memoir, 37; Gilje, Road to Mobocracy, 54-55.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Brutus, Who Seriously Considers the Impoverished State of this City; Tiedemann, Reluctant Revolutionaries, 147.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Brutus, Who Seriously Considers the Impoverished State of this City.

[37] Soldiers of the 16th Regiment, God and a Soldier.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Ibid.

[41] New York Gazette, or Weekly Post-Boy, February 5, 1770; Boston Gazette, February 19, 1770; New York Journal, March 1, 1770; McCurdy, Quarters, 194-195; Tiedemann, Reluctant Revolutionaries, 148.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Ibid.

[45] New York Gazette, or Weekly Post-Boy, February 5, 1770; Boston Gazette, February 19, 1770; New York Journal, March 1, 1770.

[46] Ibid.

[47] Ibid.

[48] New York Gazette, or Weekly Post-Boy, February 5, 1770; Boston Gazette, February 19, 1770; New York Journal, March 1, 1770.

[49] Ibid.

[50] Normand MacLeod to William Johnson, January 24, 1770 in The Papers of Sir William Johnson, edited by James Sullivan (Albany: University of the State of New York, 1922), 7:351-352; hereafter cited as Johnson Papers.

[51] Normand MacLeod to William Johnson, January 24, 1770, in Johnson Papers, 7:351-352; McCurdy, Quarters, 195

[52] Ibid; Boyer, Golden Hill and Nassau Street Riots, 166; McCurdy, Quarters, 196.

[53] New York Gazette, and Weekly Mercury, February 5, 1770.

[54] Ibid; New York Journal, February 8, 1770.

[55] Ibid.

[56] Richard Archer, As If An Enemy’s Country: The British Occupation of Boston and the Origins of Revolution (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 177-178

[57] Boston Gazette, February 26, 1770.; Benjamin L. Carp, Rebels Rising: Cities and the American Revolution (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 52; Pauline Maier, From Resistance to Revolution: Colonial Radicals and the Development of American Opposition to Britain, 1765-1776. (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1972), 193-194; Hiller B. Zobel, The Boston Massacre, (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1970), 173, 181.

[58] Boston Gazette, February 26, 1770; Henry Hulton, “Some Account of the Proceedings of the People in New England from the Establishment of a Board of Customs in America, to the breaking out of the Rebellion in 1775” in Henry Hulton and the American Revolution edited by Neil Longley York, (Boston: The Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 2010), 141-142. Archer, As If an Enemy’s Country, 178-181; Carp, Rebels Rising, 52; Maier, Resistance to Revolution, 194-195; Zobel, Boston Massacre 174-179.

![Bernard Ratzer, This Plan of the City of New York, 1769. Library of Congress. 16th Regiment’s Barracks [Red Dot]; Fly-Market [Blue Dot]; Golden Hill Riot [Green Dot]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d23a00f53f6300001f811bb/1610122524331-ISSSPY3ABMX3OXT78XSW/Weber+-+Figure+4.Ratzer%27s+New+York+City+circa+1769+copy.jpg)