How Dinosaurs Came to New York

By Lukas Rieppel

Brontosaurus display at the American Museum of Natural History Dinosaur Hall. Photographed by Kay C. Lenskjold in February, 1921. Image No. 38715, Courtesy of AMNH Library.

On February 16, 1905, the American Museum of Natural History unveiled an enormous dinosaur skeleton measuring more than sixty-five feet in length: Brontosaurus. This lumbering behemoth was discovered in a remote part of Wyoming several years earlier, and curators had just finished assembling its gargantuan bones into a free-standing display that would serve as the centerpiece of the museum’s recently inaugurated dinosaur hall. Over the next several decades, Brontosaurus became one of the most iconic dinosaurs of all time, and throngs of visitors flocked to the Upper West Side to see its fossil remains with their own eyes.

Although the exhibit was a huge success, Brontosaurus had its share of detractors as well. The New York Times quoted a “professor with large glasses” who dismissed the hullabaloo as an “absurdity” that was “in bad taste in a place devoted to science.” Still, he had to admit the dinosaur was a “splendid bit of advertising” for the museum.[1] A similar view prevailed among its scientific staff too. For example, the museum’s curator of anthropology at the time, Franz Boas, later argued that because “people who seek rest and recreation resent an attempt at systematic instruction while they are looking for some emotional excitement,” museums “must, first of all, be entertaining.”[2]

Modern audiences have become so accustomed to seeing these kinds of exhibits that it can be hard to imagine a time before dinosaurs were on widespread display in museums of natural history. But when these creatures were first discovered during the nineteenth century, their assembly into the kinds of sculptural reconstructions that are now so ubiquitous could be surprisingly controversial. One reason was that such exhibits represented a profound act of speculation, requiring museum curators to cast themselves back into the depths of time and reconstruct the functional anatomy of an animal that no human being had ever seen in the flesh. In effect, to mount such an exhibit was to put one’s credibility on the line.

Iguanodon models at the Crystal Palace, sculpted by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins. Photograph by Lukas Rieppel.

It did not help that earlier attempts to imagine what dinosaurs might have looked like soon came to be seen as woefully inaccurate and downright misguided. Scientists were especially embarrassed by a series of three-dimensional sculptures produced by the English artist Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins for Britain’s Crystal Palace Exposition during the mid-1850s. Despite working in close collaboration with the noted comparative anatomist Sir Richard Owen, Hawkins’ creations almost immediately drew sharp criticism from the scientific community. A curator of natural history at the British Museum named John Edward Gray, for example, denounced the models as unscientific nonsense, describing them as a “Crowning Humbug” and a “gross delusion.” Owen himself admitted that some parts of the sculptures were “more than doubtful.”[3] It did not help much that subsequent fossil discoveries revealed errors in the Crystal Palace dinosaurs, such as mistaking the Iguanadon’s thumb spike for a rhinoceros-like horn. In 1895, mistakes such as these led the American paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh to joke that dinosaurs

have suffered much from both their enemies and their friends. Many of them were destroyed and dismembered long ago by their natural enemies, but, more recently, their friends have done them further injustice by putting together their scattered remains, and restoring them to supposed life-like forms. So far as I can judge, there is nothing quite like unto them in the heavens, or on earth, or in the waters under the earth.[4]

Gray’s criticism of the Crystal Palace dinosaurs as a “humbug” display also points to a second reason why nineteenth-century museums worried about exhibiting fully articulated dinosaurs. Not only did reconstructing these alien creatures require a profound act of speculation. Insofar as they attracted large crowds of curious onlookers, dinosaurs also made these institutions vulnerable to the charge of pandering to popular tastes. In other words, scientists such as Marsh not only feared the public embarrassment that would result from producing an erroneous exhibit. They were equally worried about being accused of mere showmanship. For that reason, they went to great lengths to distinguish their scientific exhibits from popular spectacles of the kind that were widely associated with amusement empresarios like P.T. Barnum.

Lithograph of Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins’ proposed reconstructions of North American prehistoric creatures for the Paleozoic Museum. From the Thirteenth Annual Report of the Board of Commissioners of the Central Park, for the Year Ending December 31, 1869 (New York: Evening Post Steam Presses, 1870), Y-Bind Central, New-York Historical Society, 96514d.

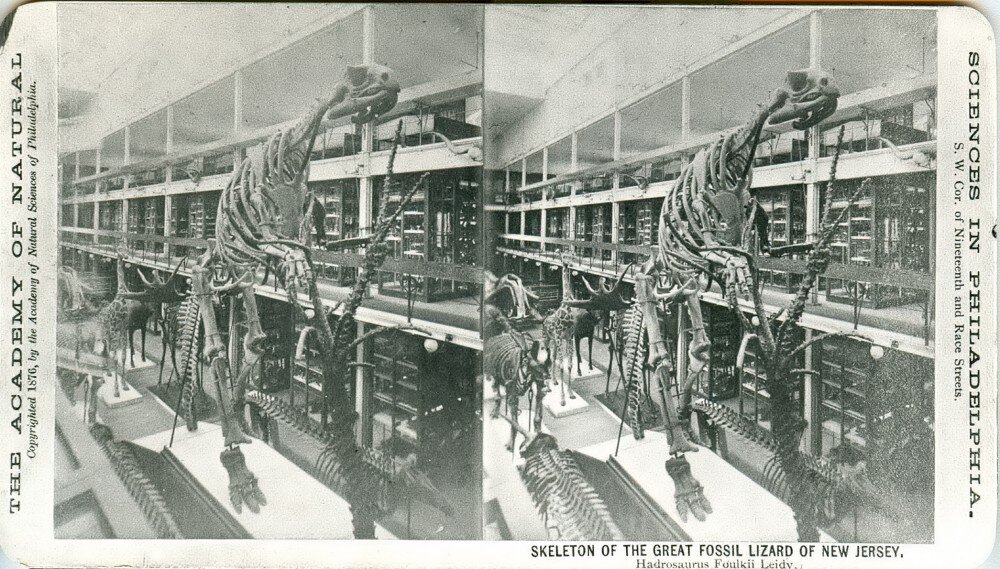

The scientific community’s anxious desire to distance itself from popular amusements was on full display at the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences. During the late 1860s, a group of New York civic leaders commissioned Hawkins to sculpt a series of American dinosaurs for a new “Paleozoic Museum” they planned to build in Central Park. In order to familiarize himself with North America’s extinct fauna, Hawkins paid an extended visit to Philadelphia, whose Academy of Natural Sciences had some of the first dinosaur bones to be found in the United States. This included the remains of a plant-eating dinosaur named Hadrosaurus, discovered in New Jersey about a decade before. As a gesture of thanks, Hawkins decided to cast the bones of this specimen in plaster and mount them into a free-standing, lifelike display.

Hadrosaurus foulkii on display at the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences, 1876.

Not long after he returned to New York, Hawkins learned that the Paleozoic Museum was not to be. Municipal elections gave Tammany Hall Democrats control over the future of Central Park, and they immediately moved to abandon the ambitious (and expensive!) undertaking. But while the dinosaur sculptures that Hawkins envisioned were never completed, the plaster cast skeleton that he had mounted in Philadelphia caused a sensation. It made such a splash that attendance at the Academy’s museum shot through the roof, prompting its scientific staff to complain “the visitors move in nearly continued streams through the narrow intervals of the cabinets, affording little opportunity for the examination of the specimens.” As a result, Academy curators decided to begin charging ten cents for admission. It was hoped that this fee would “moderate the crowds” without discouraging true students of nature from availing themselves of the educational opportunities offered.[5]

Western façade of the American Museum of Natural History’s first building, approximately 1889. Hand colored lantern slide, photographer unknown. Image ls-127-011, Courtesy of AMNH Library.

As luck would have it, a group of wealthy New Yorkers began building what eventually became the American Museum of Natural History at precisely the moment that plans for the Paleozoic Museum were scrapped. But whereas the latter was to have been sponsored by the city’s government, the former would serve as a monument to the high-minded ideals and conspicuous generosity of its philanthropic community. Wealthy capitalists such as J.P. Morgan, Theodore Roosevelt, Sr., and Anson Phelps Dodge supported a range of similar projects and cultural institutions—including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the New York Philharmonic as well as the natural history museum—in hopes of elevating their city’s status and reputation on the world stage. As pet projects of the city’s elite, it was essential for these institutions to project a strong sense of moral propriety and cultural exclusivity, and natural history fit the bill to perfection. The museum’s benefactors sought to draw a socially diverse group of visitors, hoping that exposure to nature would edify and uplift the city’s working poor. The learned study of nature was not only seen as a pious and morally uplifting leisure pursuit; it was also believed to cultivate the faculty of attention, which constituted a core pedagogical preoccupation during the late nineteenth century.

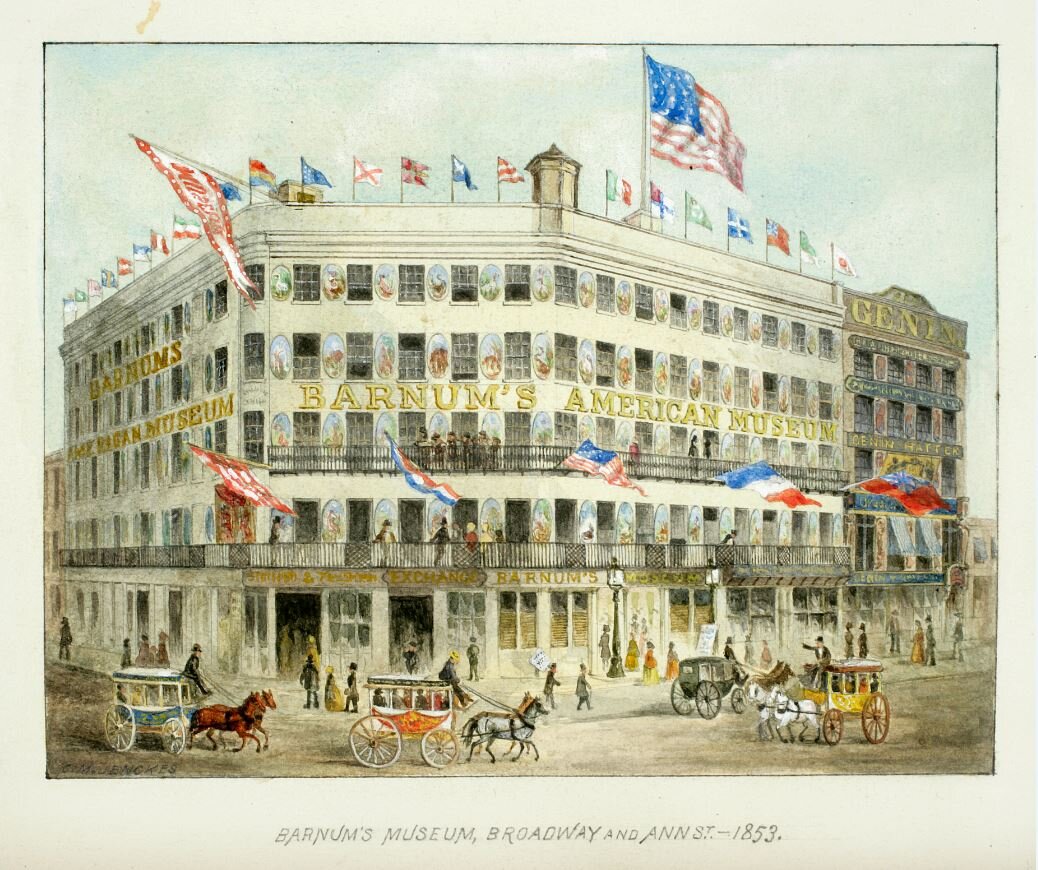

The new institution, placed alongside Central Park, initially faced especially stiff competition from dime museums, which tended to be located further downtown and had acquired a reputation for spectacular exhibitions that often rested on playful deceptions, or “humbug.” Dime museums were regarded as places that traded in “‘curiosities’ and monstrosities, cheap theatricals and legerdemain,” as an editorial in the pages of Science Magazine dismissively put it. P.T. Barnum’s establishment was the most famous by far, exhibiting a wide range of natural history specimens alongside theatrical performances, panoramic views of famous historical episodes, and other “curiosities” that catered to the diverse tastes of Victorian audiences.[6]

Exterior of PT Barnum’s Museum as it appeared in 1853, from Francis' Old New York, Manuscripts Collection, NYHS Image #84190d.

By a strange coincidence, Barnum’s museum was consumed by a fire the very same year the American Museum of Natural History finally opened its doors. But his outsized celebrity continued to cast a long shadow over the city’s cultural landscape. Indeed, dozens upon dozens of other dime museums—ranging from small storefront operations on the Bowery that were notorious for the clandestine sale of alcohol to more respectable establishments such as the Eden Musée—persisted well into the twentieth century. This made it all but imperative for the city’s social elite to distinguish their philanthropic project from the entertainment venues of commercial showmen who did not share the same pedagogical scruples or scientific pretensions. A failure to do so would have invited comparisons the new museum’s financial backers most desperately sought to avoid.[7]

A papier-mâché mermaid from the same Moses Kimball collection that once included the Feejee Mermaid exhibited by P. T. Barnum. Exhibited Peabody Museum, Harvard University, and made available through Wikimedia Commons.

Even before the new museum venture got off the ground, for example, an editorial in the New York Herald argued that

Private individuals may get up a show but a museum, to be of sterling value, must be a public institution. We have had some experience in this city with museum mongers for some years past, one of them the charlatan general of showmen, whose proudest boast was the impudence with which he imposed upon the public, and whose sole reputation is based upon the shameful exposure of frauds of which he himself is the chronicler.[8]

Wealthy philanthropists’ goal of distinguishing themselves from the competition was made all the more acute because they embraced a radically different vision of what a museum ought to accomplish. In their eyes, a museum properly so-called should not challenge visitors to determine the meaning or authenticity of its exhibits themselves. Barnum had famously invited audiences at his museum to judge whether his prized Feejee Mermaid was not in fact just the anterior part of a monkey stitched to the posterior end of a fish. The natural history museum, by contrast, sought to offer an authoritative account of the latest, most trustworthy science. To that end, in addition to mounting lavish exhibits and holding exclusive soirées, it also hired a team of in-house naturalists charged with adding new facts to the storehouse of reliable knowledge. In effect, it was hoped that by broadcasting the backstage work of its research scientists, the museum could lend credibility to the front-stage work being done in its public galleries. As a result, museums like the one in New York began to acquire the complex institutional mission they still have today, which marries original research with popular education.

If it was going to succeed at uplifting ordinary New Yorkers, however, the museum also had to attract a large and socially diverse audience into its exhibition hall. This is where dinosaurs really excelled! Not only were dinosaurs considered to be scientifically prestigious and distinctly American, but they could be relied on to draw a crowd. This is precisely what happened when the massive new Brontosaurus first went on display. “It is gratifying to report the unusually large increase in the number of visitors,” curators proclaimed in the 1905 annual report. “This growing popularity of the Museum is due in part to the opening of several striking exhibits,” they continued, “particularly the huge Brontosaurus.”[9] Hence, dinosaurs quickly emerged as a star specimen of the first order, the curator’s preferred means of meeting the complex institutional goals of their financial benefactors.

Curators and Technicians at the American Museum of Natural History Assembling the Brontosaurus Display, 1904. Image no. 17506, photographed by A. Thomson, Courtesy of AMNH Library.

In private, however, museum curators had to admit that mounting a dinosaur required more than a little showmanship. They worried endlessly about making themselves vulnerable to the charge of having sacrificed scientific rigor to attract visitors, especially when it came to assembling the bones of a long-extinct creature into a lifelike and imposing display. “However willing [the visitor] may be to accept on faith the reconstructions of [these] skeletons,” curators lamented, the dinosaur hall “remains to him somewhat of a fairy tale, a fancy imaginative world peopled with ogres and dragons.” For that reason, they went out of their way to advertise the detailed work required to mount the museum’s imposing dinosaurs and sought to shore up the exhibits’ epistemic foundation. Printed guides, for example, described at great length how the fossil remains of these creatures had been discovered and excavated. They also recounted the painstaking process required to reconstruct the functional anatomy of these alien creatures, explaining how paper cutouts were used to study the “action and play of the muscles on the limb of the Brontosaurus” and “the bones adjusted until a proper and mechanically correct pose was reached.”[10]

The massive Brontosaurus that was unveiled in New York during the year 1905 was thus hardly an uncontroversial object of nature. Displays such as this involved a complex negotiation between a number of conflicting goals and desires, one that required museums to balance the popular taste for public spectacle against the curators’ sense of scientific propriety and the desire among their financial benefactors to be remembered as generous and high-minded philanthropists.

Lukas Rieppel is a historian of the life, earth, and environmental sciences, the history of museums, and the history of capitalism, especially in nineteenth and early twentieth century North America. He recently published a book on the history of dinosaur paleontology in the commercial context of North America's Long Gilded Age, as well as a co-edited volume entitled "Science and Capitalism: Entangled Histories."

[1] “Old and Young Call to See the Dinosaur,” New York Times, Feb. 20, 1905, p. 12.

[2] Franz Boas, “Some Principles of Museum Administration,” Science, vol. 25, no. 650 (June 14, 1907), pp. 921–933.

[3] See James A. Secord, “Monsters at the Crystal Palace,” in Models: The Third Dimension of Science (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2004), 157–58.

[4] O.C. Marsh, “Restoration of Some European Dinosaurs, with Suggestions as to their Place Among the Reptilia,” American Journal of Science, 3rd ser., vol. 50 (Nov. 1895), pp. 407–412.

[5] "Report of the Curators" in Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Science of Philadelphia, vol. 21 (1869), pp. 234–235.

[6] N.H. Winchell, “Museums and their Purpose,” in Science, vol. 18, no. 442 (Jul 24, 1891), pp. 43–46.

[7] On Barnum in particular, see Bluford Adams, E Pluribus Barnum: The Great Showman and the Making of U.S. Popular Culture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997); James Cook, The Arts of Deception: Playing with Fraud in the Age of Barnum (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2001). On Dime Museums more broadly, see Andrea Stulman Dennett, Weird and Wonderful: The Dime Museum in America (New York: New York University Press, 1997); Brooks McNamara, “A Congress of Wonders: The Rise and Fall of the Dime Museum,” Emerson Society Quarterly 20, no. 3 (1974), pp. 216–234.

[8] “A National Museum Wanted,” New York Herald, July 12, 1866, p. 4.

[9] Annual Report of the American Museum of Natural History (New York: American Museum of Natural History, 1905), p. 29.

[10] William Diller Matthew, Dinosaurs, with Special Reference to the American Museum Collections (New York: American Museum of Natural History, 1915), pp. 65, 116. See also William Diller Matthew, “The Pose of Sauropodous Dinosaurs,” The American Naturalist, vol. 44, no. 525 (1910), pp. 547–560.