"Imagination Aided by the Painter's Brush": William Ranney and the Creation of the Purchase of Manhattan, 1844–1909

By Stephen McErleane

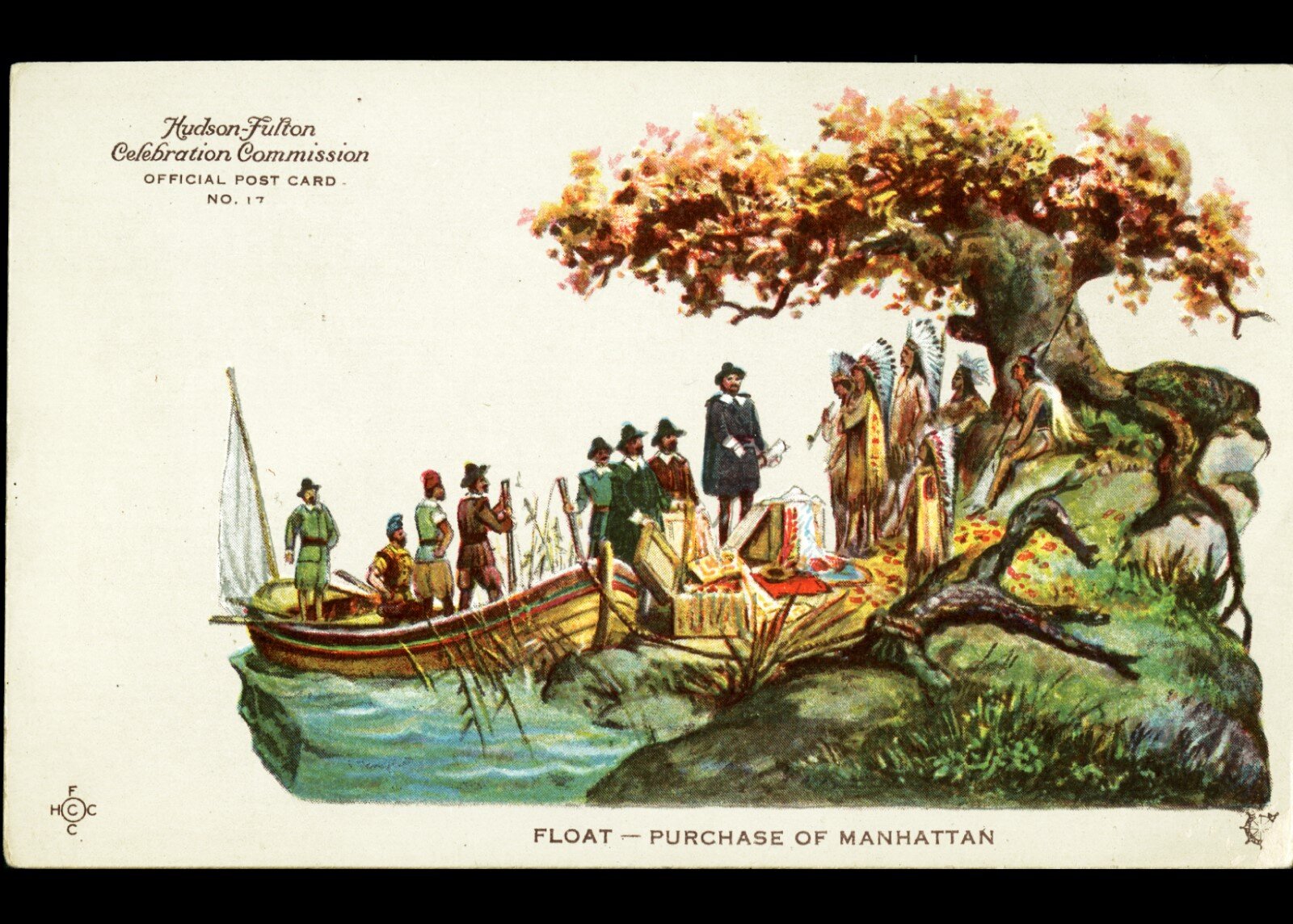

“Twenty-four bucks worth of beads and trinkets. This whole island.” One can easily imagine this remark from any of the more than 1,000,000 parade spectators on Fifth Avenue as they watched the “Purchase of Manhattan Island” float go by in the 1909 Hudson-Fulton Celebration. The fifteenth in a procession of fifty-four historical floats depicting notable events, persons, and places in the history of the Hudson River region, the thriftily constructed display of paper-mâché and painted canvas portrayed the legendary 1626 transaction in which the Dutch allegedly purchased the island for the paltry sum of twenty-four dollars.

Although it is now a fundamental piece of the city’s earliest history, it was not until 217 years after the event that New Yorkers first learned of the transaction.[1] The story surfaced in 1844 and filled a void in a city largely ignorant of its earliest history, a city whose Dutch origins had, as Washington Irving wrote, left it with “an antiquity… extending back into the regions of doubt and fable.” Based on a single sentence in a contemporaneous letter reporting the news of the purchase, the story’s lack of detail and frequent retelling encouraged imaginative leaps. In the decades that followed the letter’s discovery, historians, artists, and others—who could now reach a larger audience due to a media revolution—obliged.

Of all the representations of the purchase, its images have had the most influence on the popular imagination, both directly and indirectly through their influence on authors. Usually comical, sometimes intentionally so, these paintings, drawings, etchings, engravings, and the like often portray a group of Dutchmen and Indians flanking a chest of goods that is overflowing with beads, cloth, trinkets, and other colorful European goods. Aided by new technologies, images in general were gaining influence just as the Manhattan purchase story surfaced. As historian Gregory Pfitzer wrote in his book Picturing the Past, there was a “midcentury trend in which images began to compete with words for preeminence in historical texts. History paintings executed in the ‘grand manner’ had always had a usurping effect on the historical imagination,” wrote Pfitzer, “but by the mid-nineteenth century [improved] technologies of reproduction increased greatly the circulation of and inviolability of [such] canonical works.” The newly-available medium excited authors, who touted its value. In 1855 the Reverend Thomas DeWitt noted that reproduced paintings, including one of the Manhattan purchase, “gave a value and interest to [a] pamphlet” that “it could not possess otherwise.” Likewise, James Grant Wilson wrote in 1891 that “Imagination, aided by the painter’s brush, has brought [the Manhattan purchase] scene before the minds of later generations.”

Known today mostly for his influential paintings of the American West in the nineteenth century, William Ranney’s 1853 painting of the famous land deal has been largely overlooked.

Despite the influence of images of the Manhattan purchase, the most influential has been surprisingly overlooked: an 1853 painting by the celebrated American artist William Ranney. Best known for his paintings of life on the nineteenth-century American frontier, Ranney’s work was featured in The New York Times in 2007 under the title “Creating a Myth with Canvas and Paint.” That myth was not the purchase of Manhattan, but Ranney’s depictions of nineteenth-century white Americans as “heroic, enterprising folk taming a savage land.” It is a delightful irony, then, that, with his reputation as a myth-maker, the influence of Ranney on the Manhattan purchase myth has been largely forgotten.

Ranney’s purchase painting deserves our attention for a few reasons. First, it was in all likelihood the first image of the legendary land deal, and was clearly the model for subsequent depictions of the event. Second, it contains the first inclusion in an image or text of the myth’s infamous beads, a story for another time. Third, and this is our focus here, is the circumstances behind its creation and composition. The painting is a prime example of how representations of historical memory are often a hodgepodge of symbols of various origins. In this case, Ranney’s painting borrowed its core elements from another (at the time) much more famous land deal between American colonists and Indians, the mythical success of which a group of boosterish New Yorkers sought to emulate.

The first appearance in print of New York’s late-arriving origin myth was in January of 1844 when budding historian E. B. O’Callaghan, then a writer and editor for the Albany journal the Northern Light, shared the following:

We furnish below for the readers of the Northern Light an interesting and curious letter, recording among other important events, the purchase of the Island of Manhattans, two hundred and seventeen years ago, by the Dutch, from the Indians, for the sum of sixty guilders, or twenty-four dollars! The tract conveyed for this trifling sum contains 13,920 acres.

O’Callaghan’s source was a recently discovered letter written in 1626 by Pieter Schagen, a delegate to the States General of the Netherlands, in which Schagen relayed the news that the Dutch West India Company’s representatives had “purchased the Island Manhattes from the Indians for the value of 60 guilders.” No doubt seeing how such an incongruity would resonate with his readers, O’Callaghan converted the sum of sixty guilders into twenty-four dollars, entering this “trifling sum” into the city’s collective memory.

The story spread rapidly, usually as brief mentions in newspapers and periodicals with headings like “Cheap!” But one group of New Yorkers aimed to elevate the purchase to one of the most notable events in colonial American history. Led by institutions like the New-York Historical Society and the Collegiate Dutch Reformed Church, this group comprised something of a city elite: well-off, well-educated New Yorkers with deep, usually Dutch, roots in the city. For these gentlemen, the purchase wasn’t notable, as most would assume today, because it was the ultimate swindle. Quite the opposite. The purchase story proved that an honest business deal had laid the foundation for their great city. As Simeon DeWitt Bloodgood argued at a meeting of the New-York Historical Society in 1844, the purchase “places us on as high ground of justice and right in the occupation of the soil as the land of [William] Penn.” It displayed a “quiet, peaceful and honest possession” of the island. The Society’s favorite historian, John Romeyn Brodhead, continued this argument in his 1853 history of New York. Before the purchase, he noted, the Dutch had possession of the island “only by the right of first discovery and occupation.” The purchase then “superadd[ed]” a “higher title.” Brodhead did not miss the opportunity to compare the purchase to Penn’s treaty. The purchase of Manhattan, he wrote, “one of the most interesting [events] in our colonial annals, as well deserves commemoration, as the famous treaty, immortalized by painters, poets, and historians, which William Penn concluded, fifty-six years afterward, under the great elm-tree, with the Indians at Shackamaxon.”Not only did New York have an event of similar stature, it was more than half a century older!

Completed in 1827, this sandstone relief panel depicting Penn’s treaty with the Delaware Indians is one of four such panels in the U.S Capitol Rotunda, each depicting an ostensibly formative event in early America. None of the four events are from New York, the others being "Conflict of Daniel Boone and the Indians,” "Landing of the Pilgrims,” and "Preservation of Captain Smith.”

The Treaty of Shackamaxon—the fabled agreement between William Penn and the Delaware Indians that was purportedly signed in 1682—was by the 1850s firmly established as one of the nation’s core founding myths. With a well-established oral tradition and celebrated works of art like Benjamin West’s 1771-72 painting and a sandstone relief panel above the doors in the United States Capitol Rotunda, the story of Penn’s treaty was well known to Americans as a symbol of fair dealings with Indians, a symbol mid-nineteenth-century Quakers fully embraced. In the 1870s, a Quaker federal Indian agent even took an engraving of West’s painting with him to his job out West.

So when William Ranney’s painting The Purchase of Manhattan Island by the Dutch from the Indians in 1626 appeared at the National Academy of Art in New York City in 1853, viewers no doubt appreciated what was at the heart of Ranney’s composition: an argument about the historical importance of the Manhattan purchase vis-à-vis Penn’s treaty and, more broadly, about the unfair lack of attention the new nation had thus far given New York City’s history. The inspiration for Ranney was Benjamin West’s famous ca. 1771-72 painting of the event. The similarities between the two paintings are clear. Note the chest of goods in the center and the orientation of the parties. The tree on the right in Ranney is likely a reference to the great elm tree at Shackamaxon. The kneeling figure leaves no doubt of Ranney’s intentions to follow West. This famous set of symbols, then, known to New Yorkers to represent the purchase of Manhattan, more accurately reflects a co-opting of a set of symbols. In Ranney’s painting those symbols represent an argument about relative historical importance. Needless to say, that meaning is lost on viewers today.

Benjamin West’s 1771–72 painting of William Penn’s famous treaty was commissioned by William’s son, Thomas.

Unfortunately, we know little of the circumstances surrounding Ranney’s painting. It was likely commissioned by Dr. James Anderson, as it was he who lent it to the National Academy in 1853. Anderson was an elder in the Collegiate Dutch Reformed Church in New York City and “a descendant of one of the oldest Dutch families in [the] country.” Anderson’s son-in-law, Charles L. Vose, had owned and possibly commissioned at least two of Ranney’s paintings and therefore may have suggested Ranney to Anderson. Ranney was also a New Yorker of sorts. He may have even been able to see the rapidly-growing island of Manhattan from his studio in West Hoboken, New Jersey, today’s Union City. Unfortunately, it seems neither Anderson nor Ranney left a collection of personal papers. Anderson does turn up here and there in a search of the city’s newspapers, most notably in a detailed story recounting the suicide, by the muzzle of an old-fashioned navy revolver, of his above-mentioned son-in-law, Charles L. Vose.

Fittingly, the location of the painting has also been a mystery. In the winter of 1923 it was “discovered” at Rutgers University, where it had hung unnoticed “for many years.” Apparently, no one knew where it came from or how long it had been in the possession of the college. It seems to have then gone missing again, as a 2006 exhibit catalog could only provide a black-and-white photo. Oddly, a full-color photograph of the painting appears in a 2003 publication, in which the painting is said to be located in a private collection.

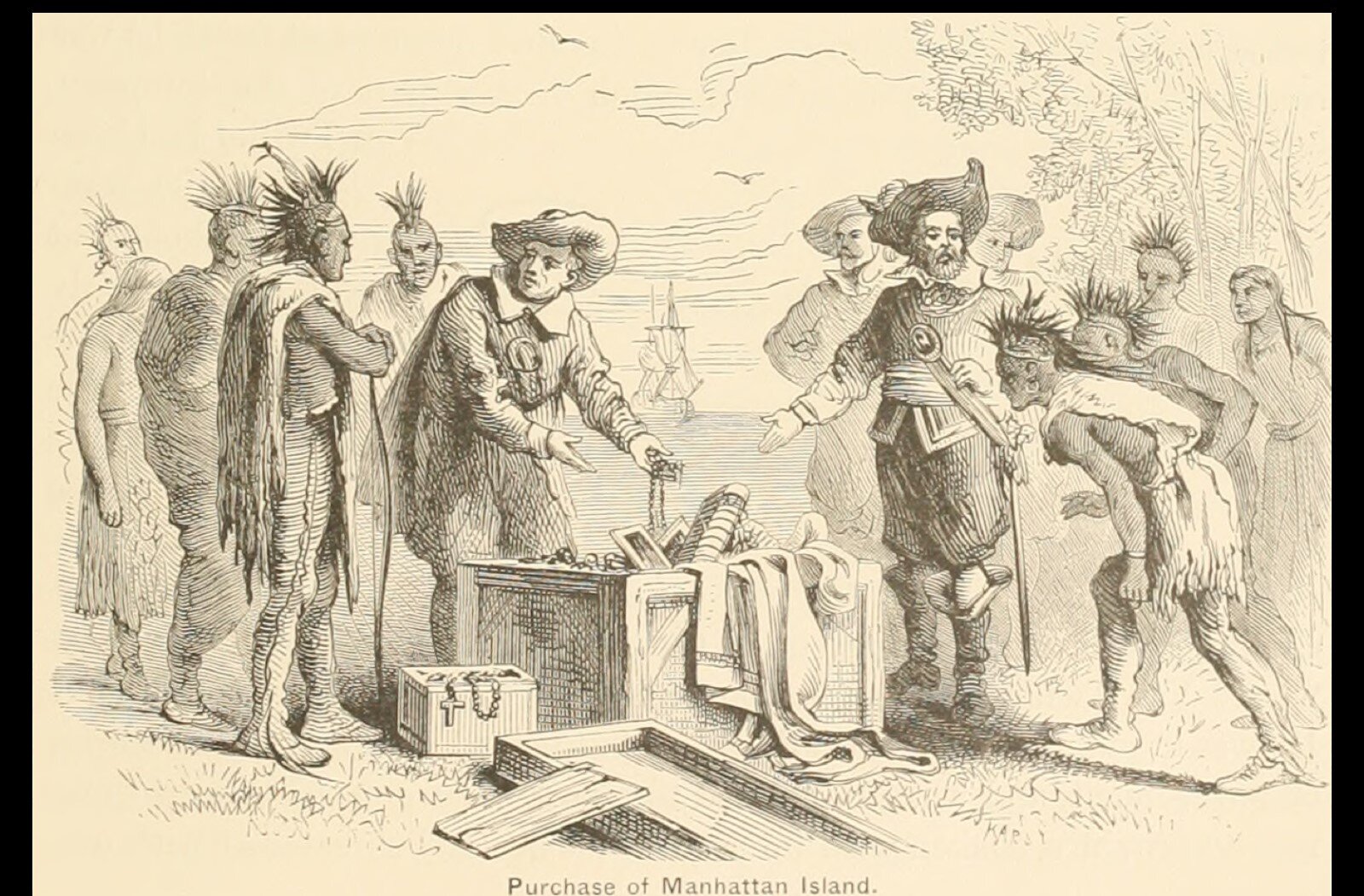

An illustration from a 1921 reprint of Martha Lamb’s history of the city.

Ranney’s painting was subsequently copied by artists and authors alike. With meager documentary evidence, nineteenth-century historians relied on Ranney’s painting and its offspring for their descriptions of the purchase. Martha Lamb, who is most likely the first historian to mention beads in print (remember that Ranney’s painting introduced the beads), wrote in 1875 that the Dutch “offered beads, buttons, and other trinkets” for the island. The illustration in a 1921 reprint of her book is clearly taken from Ranney. In 1884 Benson J. Lossing reported the price of the island as “cheap trinkets, implements of husbandry, and weapons.” In 1888 Charles Burr Todd lifted the scene right from Ranney when he wrote of a “strong sea chest” that “stood open between the two parties, filled with beads, buttons, ribbons, gayly embroidered coats, and similar articles.”

The Hudson-Fulton Celebration Commission issued a series of postcards to commemorate the event, including one for each of the 54 floats in the “Historical Pageant.”

Historical interpretations changed slowly in the nineteenth century. The purchase story we see in the 1909 Hudson-Fulton Celebration is identical, even word for word, to what John Brodhead wrote in his 1853 history of the city. Note the elements in the official postcard (unfortunately I have not been able to find a photograph of the actual float) including the reference to Penn’s celebrated elm tree. The direct line from West’s Penn to Ranney’s Manhattan purchase is unmistakable. The official description noted that the purchase was “as honorable, as important and as noteworthy” as was Penn's treaty, an assertion taken word-for-word from Brodhead’s 1853 history.

At the time of Ranney’s 1853 painting, New Yorkers got the reference to Penn. “At the National Academy, a few evenings since,” read the Knickerbocker Magazine, “we stood near Ranney’s picture representing the purchase of Manhattan Island from the Indians, in 1620 [sic]. A long-legged dandy, with a few thinly-settled hairs on his upper lip, was just before us. Being asked the subject of the painting by a by-stander, he looked ‘wondrous wise’ and replied: ‘It’s William Penn treating the Indians!’” It’s hard to say how many in 1909 recognized the influence of West’s painting on the then-accepted scene of the purchase, but you’d be hard-pressed to find anyone who does today. The scene eventually just became a symbol of the purchase of Manhattan, leaving behind the unique historical circumstances surrounding its composition, circumstances one must appreciate to understand the myth and the reasons for its survival.

Stephen McErleane is the director of the New Netherland Institute in Albany and a doctoral candidate in history at the State University of New York at Albany, where he studies the seventeenth-century Dutch colony of New Netherland in histor(iograph)y and memory.

[1] We know little about the 1626 transaction. We don’t know the date, though some figure it was in May shortly after the arrival of New Netherland director general Peter Minuit, who we don’t know for sure presided over the sale. We do not know the identity of the Indians present, so we can’t say that it was purchased from the “wrong” Indians. This farcical take likely originated in a 1959 article by Nathaniel Benchley. There was almost certainly a deed of sale, but we don’t know what came of it; like most of New Netherland’s earliest records, its location is unknown. The only known reference to anything like it appears in 1670 in the records of New York (the English seized New Netherland in 1664) when an English representative claimed that, according to the records, the island was “bought & paid for 44 yeares agoe.”