“Are these not my streets?”: May Swenson, New York City, and the Federal Writers Project

By Margaret A. Brucia

This is the first of two posts based on the early life of the New York poet May Swenson (1913-1989) and her work for the Federal Writers Project.

Drawn to New York by her exposure to Lost Generation authors and the work of Alfred Stieglitz and his circle of artists, May left the security of her loving Mormon family in Utah during the depths of the Great Depression. After struggling to hold a series of low-paying positions, withering prospects for employment threatened her continued existence in New York. By a devious route, May joined the ranks of the Federal Writers Project, plunged into New York’s cauldron of creativity, and went on to become a leader in the field of modern poetry.

“I pledge you, I pledge myself to a new deal for the American people,” promised Franklin Delano Roosevelt on July 2, 1932.[1] Three years later, he created the Works Progress Administration (WPA), the juggernaut of his New Deal. Federal Project Number One, a division of this massive public works program, harnessed the talent of creative artists on relief, with a subdivision, the Federal Writers Project (FWP), specifically designated for writers. Applicants with even the vaguest literary credentials met the requirements for a job. But not May Swenson.

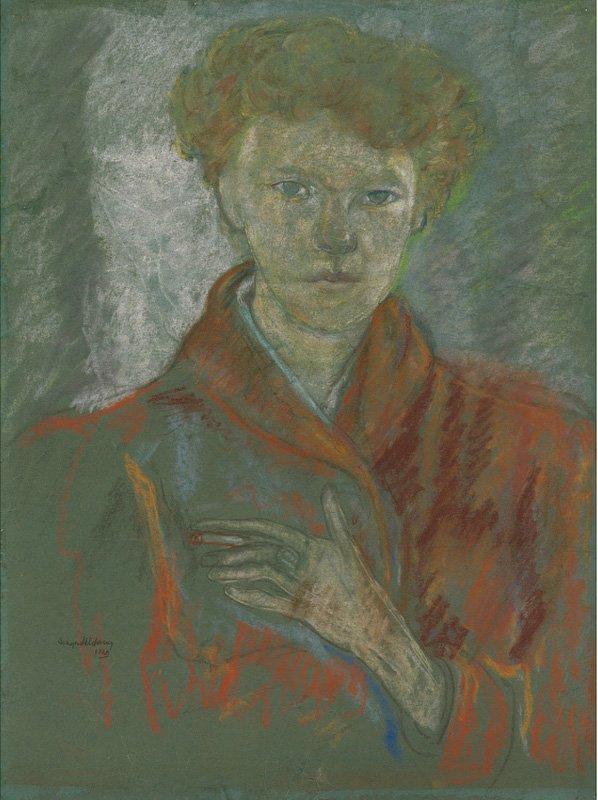

Portrait of May Swenson by her friend, the artist Beauford Delaney, 1960 [© Estate of Beauford Delaney, by permission of Derek L. Spratley, Esquire, Court Appointed Administrator, Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY].

Despite holes in her shoes, shabby clothes, a poor diet, bleak prospects, and dwindling savings, the aspiring poet and twenty-three-year-old was disqualified from joining the Workers Alliance in New York City because her father, a teacher at Utah State Agricultural College, held a job. Without relief-roll status, she was deemed ineligible for FWP assistance.

May had come to New York determined “to dip up the sea in spoonfuls.”[2] She arrived on July 20, 1936, fulfilling a secret dream she had nursed through her college years in Logan, Utah. Raised by Swedish immigrants in a deeply religious Mormon family, she was the eldest of ten children. Household chores and the responsibility of minding siblings left her little free time. Yet she read voraciously and, at the encouragement of her loving and sympathetic father, began a lifelong practice of keeping a diary. Writing poetry became an early passion.

In 1935, a year after her graduation from Utah State, she left home, hoping to be a reporter for the Salt Lake City Tribune. Instead she was hired to sell ads. In the late spring of 1936, with her own scant savings and $200 from her father, she set out for New York, with no intention of returning to Utah. The night before her journey, she wrote:

new roads—a new city—life, life you are there, ferociously awaiting me—far—in another city.… I am writing in this book for the last time in this life before going away on a bus… New York is to be my hometown … New York—my city—Walt Whitman’s and mine. You Walt Whitman & Thomas Wolfe—soon Alfred Steiglitz [sic]—soon to be in that City—[3]

At first, her spirits soared. She shared a tiny apartment on the Upper West Side with two Mormon women. “And this is my room—the view from the window is a patch of brick wall. I like it here,” she wrote.

She embraced the city’s endless cultural opportunities, taking in a performance of the “Daphnis and Chloe” at the Lewisohn Stadium soon after she arrived, despite her meager savings (“I have $69 left.”) No stranger to ballet, she was as interested in the ethos of individual dancers as in the quality of their performance. Months earlier, a pas de deux performed by principals in the Ballet Russe at Kingsbury Hall in Salt Lake City had inspired one of her more memorable poems.

At the Ballet

The dancer places his hands lightly

around the waist of the ballerina

as she descends along his thigh

Her legs parted

one knee bent

the truncated toe of her slipper

touching his pouted groin

she glides lingeringly

down his chest and thigh

His haunches snugly divided

as those of a horse

are pressed together

His feet on toe

are accurate as hooves

Sweat glistens

in the hollow of his throat

but her profile

is a cameo of cool repose

Of what is he thinking

as her flat torso

passes between his palms

as her puffed skirt

floats above her hips

as her hair brushes his nostrils

as her toe for a moment rests

upon his groin

as she descends

like a gossamer swan

he has caught in flight?

Not of her warmth

for she is like marble

Not of her weight

for she is light as smoke

Perhaps of her beauty

which like a blossom without scent

a fruit without taste

ignites his mind with ecstasy

and drains his body of all desire

May was enthralled with the actor Lesley Howard.

At the Imperial Theatre, she was transfixed by Leslie Howard’s Broadway performance as Hamlet, raving about the “slim body” and “precious loins” of the matinee idol. She visited the Museum of French Art on Fifth Avenue, between 48th and 49th Streets, and vowed to return “again and again.” She went often to see art films and the latest Hollywood releases. Like so many transplants, she became possessively proud of her new city, strolling from 109th Street, down Broadway, to 45th Street “negligently, like a Lord—for do I not own this? Are these not my streets?” But she couldn’t long ignore her diminishing savings: “I have $40—my rent due.”

Determined to support herself, she rented a typewriter and placed an ad in The New York Times.

WRITER, college degree, trained arts,

literature, keen, healthy, physical, mental

poise, age 23, do anything progressive and

legitimate that nets living.[4]

The ad generated a reply from Paltial Rosen, a wealthy Russian businessman and amateur playwright, whom she interviewed in her apartment. “Mr. Rosen came in, sat in my room, talked louder, louder, LOUDER,” she noted in her diary, and “kept lighting his cigars a thousand times—goink, & comink.” But she delighted at the prospect that “maybe the impoverished ‘writer’ ha[s] a job!”

Rosen wined, dined, and fawned over his “darlink” May and offered her twenty dollars a week to compose a play about his life. “Today the pact was made—May and Paltial… Plat is my boss and collaborator—and lover, to be sure. Why not? Just like a French novel you know.” Her ebullience spilled onto the page. “Well I am in New York. This is the world. This is my life in the world—this is May Swenson drawing breath—partaking of this air—Being for this space of time—me—May Swenson—I am.”

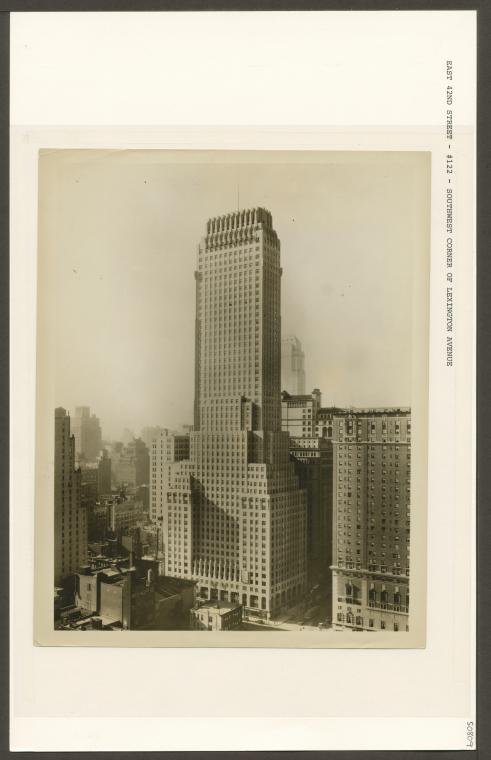

The Chanin Building, where May first worked in New York City [photograph by Underwood & Underwood, from the collection of the New York Public Library].

Rosen set her up in an office in the Chanin Building, a stunning art deco skyscraper at 122 E 42nd Street, near Grand Central Terminal. “I have no idea where this topsy turvy whirlwind of insane adventure will lead me,” she wrote. But she was fired several months later, when she failed to produce a satisfactory draft of Rosen’s play.

Her next ad brought work as executive secretary/copy editor/receptionist for Howard Ketcham, whose headquarters were at the sleek, new Rockefeller Plaza. Ketcham, an authority on color theory, had established his own color-design agency, advising large companies on effective color choice. May was impressed with her surroundings, but she considered her co-workers’ obsession with color tiresome, even ridiculous; one day, a colleague remarked over lunch on “the value of the mustard on the chroma of the cheese!” They, in turn, regarded her as an unsophisticated Westerner. The employment, although lucrative, was short-lived.

But if her eventual dismissal was no surprise, it obviously discomfited her. “I am a flop—a n’er-do-well—a failure—a good for nought—lazy—incompetent, inefficient—wishy washy—unbalanced,” she berated herself in the diary. As her self-confidence plummeted, she longed for the comfort of family. “I started a letter to home—but tore it up—too sentimental.” Alone and discouraged, she found solace on the solid steps of the Public Library between “the haughty sinewy stone lions crouching on either side—beleaguered by pigeons perched in their manes.”

Anticipating a new round of job interviews, she worried about the shoddiness of her deteriorating wardrobe and took to shoplifting. “I swiped a dress—it’s blue, white & red—wearing it out under my other.” Feeling better in new clothes, she began exploring some of New York City’s galleries, particularly taken by the work of modernist artists.

Determined to make connections in New York’s vibrant literary and art scene, within two-and-a-half weeks of her visit to “An American Place,” she established a friendship with both Alfred Stieglitz and William Einstein:

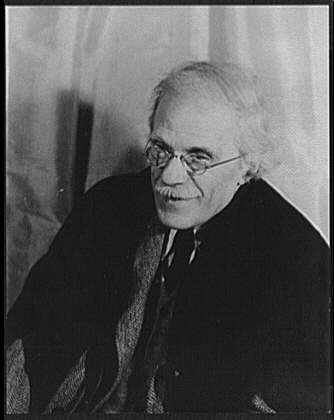

Alfred Stieglitz, photographer and promoter of modern art [photograph by Imogen Cunningham].

I talked with Stieglitz … tufts of hair bristling from his ears. I promised E[instein] I would bring a poem…. they were so nice to me …..

I keep thinking of Stieglitz and him—and me and my poem. Where am I going? What is this? Where am I? I’m not very nice I’m afraid. I want to be beautiful. I want beauty. I want that precious thing they have there at The Place. I shall go there again, yes?

She marketed herself again in the Times but this time identified as a:

YOUNG WRITER, keen for work, experi-

enced author’s assistant, typist, research,

magazine and newspaper reporter, ghost

writer; university degree and references.[5]

Then, success: “I rode the subway down to the Village—Morton St.—to see a dame Anzia Yezierska—who has a MS wants typed.” Born in Poland, Yezierska had grown up on the Lower East Side, and drawing from her experience, became a prolific writer of short stories and novels treating the theme of acculturation, especially among Jewish immigrant women. She had just returned to New York City, after suffering a mental breakdown following her success in the early 1920s and subsequent financial decline. By now a forgotten literary figure in her fifties and unable to support herself, she joined the FWP. But with its massive two-volume guide to New York City nearly complete, she had been assigned the mundane task of cataloging all the varieties of trees in Central Park. Dissatisfied, Yezierska left the FWP and, hoping to jump-start her career, hired May as her typist.

Author Anzia Yezierska was May’s employer.

Yezierska grew fond of her young assistant and soon became May’s mentor, confidante, and matchmaker. She arranged for May to meet her nephew, Arnold Kates, a divorced advertising man. At first offended by the meddling, after several Scotch-and-sodas followed by dinner at the Brevoort, May admitted in her diary, “I like him—I really like him.” After all, he had “nice wrists,” and freely quoted Browning and Milton. At Jack Dempsey’s bar a few weeks later, she leaned over and asked tipsily, “What’s the chance of sleeping with you tonight?” In the morning, after “a friendly time of it,” she lingered in Kates’s apartment after he, “looking spruce,” left for the office. She left some time later with “his Joyce and Autobiography of Freud” to wander through the Village looking for an apartment. “What will happen to me? I make so little money—I shall have to live in a hole—$3 a week will be the limit for me.”

Kates was financially secure, and Yezierska urged May to marry him. But marriage, like abandoning the City, never seemed a viable option. “Thank god I am free—thank god I do not owe him,” she wrote. Still, it was clear that May needed assistance. Yezierska explained that she could receive relief from the Workers Alliance if she was willing to game the system. She needed only to fabricate a convincing personal narrative that included two years residency without any means of financial support.[6] May was desperate and had no scruples about lying, claiming to be an orphan who had come to New York two years earlier with no siblings or relatives, except an aunt whose whereabouts were unknown. Her application was accepted in March 1938, and she then applied for a job with the FWP.

On August 4, 1938, May drew a banner in her diary. It bore a heart surrounding the letters W P A interspersed with her own initials, M S. Above her sketch, she wrote triumphantly:

On this day in the year of our Lord Nineteen Hundred and Thirty-Eight, one M. Swenson joined the Federal Writers Project of Greater New York, her journey toward this end having been marked with deep travail.

Unfortunately, May’s timing was off. Her work for the FWP began just as the newly formed Special Committee on Un-American Activities began launching anti-communist salvos at writers working for the FWP. May would not escape unscathed.

In Spoonfuls

I demand of myself

when I say, “You must write these poems,”

that which in the old tale,

the mistress charged of her ambitious lover,

that he go with a teaspoon to empty the sea.

Yet my love is even this great

and unreasonable,

that I do run down again and again

to the dripping sands,

knowing that one thousand lives

spent undeviatingly

by one a thousand times so strong

as I,

could not perform it.

Yet I go

(depending on this one moment

of eagerness)

to dip up the sea in spoonfuls.

Acknowledgements

©1952, 2000, 2013 May Swenson and Literary Estate of May Swenson. As included in Swenson: Collected Poems (Library of America, 2013). Used with permission of The Literary Estate of May Swenson. All rights reserved. Thank you to Carole Berglie and The Literary Estate of May Swenson for providing access to the Swenson materials, and to Joel Minor and the May Swenson archives at Washington University, St. Louis.

Many thanks to Peter Amram for his adroit suggestions.

Margaret A. Brucia has taught Latin in New York and Rome for many years and is a Fulbright Scholar, a recipient of a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Humanities, and a Fellow of the American Academy in Rome. She is currently writing a biography of May Swenson.

[1] For a digital facsimile of Roosevelt’s speech, now in the archives of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library in Hyde Park, New York, see https://fdrlibrary.files.wordpress.com/2012/09/1932.pdf.

[2] May Swenson, “In Spoonfuls,” in Swenson: Collected Poems, ed. Langdon Hammer (New York: Library of America, 2013), 539. “In Spoonfuls” was written in 1936 and published posthumously in Worcester Review (Fall 2000).

[3] The Literary Estate of May Swenson. All subsequent quotations of May Swenson’s words are from diaries in The Literary Estate of May Swenson.

[4] The New York Times, August 16, 1936.

[6] The New York Times, August 22, 1937.

[7] For Anzia Yezierska’s experience gaining access to the FWP, see Jerre Mangione, The Dream and the Deal (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1996), 156-57.