On the Wall: Four Decades of Community Murals in New York City

By: Janet Braun-Reinitz and Jane Weissman

Nancy Sullivan, Not For Sale, 1985, from Artmakers Inc.'s La Lucha Mural Park, Lower East Side, Manhattan, photo (c) Camille Perrottet.

An exclusive excerpt from their new book

Murals are the people’s blackboard.

– Pablo Neruda

I know that mural. I live near it. . . . I remember when the mural was painted. It’s really a part of our neighborhood. . . . I see that mural every day from the elevated train on my way to work. . . . Our mural has been there for years. Now it’s faded and the paint is peeling. It’s very sad. . . . Last week, when I walked by my favorite mural, the wall had been whitewashed.

Such comments inevitably figure in any conversation about community murals. People who live, work, or pass by murals note, remember, and accurately describe them. Community murals—collaborations among artists, neighborhood groups, and mural organizations—have energized New York City’s visual landscape since 1968, the four decades covered in this cultural history. A singular art form, these large-scale and site-specific works reflect the social, cultural, and political climate of their times and the neighborhoods in which they are located. Community murals beautify, educate, protest, celebrate, affirm, organize, and motivate residents to action. They are a window into the unwritten history of a neighborhood, providing a depth of understanding equal or perhaps greater than that provided by “official” records.

Over the past 40 years, local organizations have enthusiastically adopted outdoor community murals, sponsoring more than 500 of them throughout the city’s five boroughs. The ideal collaboration involves every phase of the mural-making process, from germination to dedication, with artists and representatives of neighborhood groups embracing their roles to the fullest. This interaction depends on the mutual respect of everyone involved and distinguishes community murals from commissioned and artist-initiated murals and most memorial walls.

Every year, community murals disappear—and with them their histories. As time passes, murals inevitably fade—sun, wind, rain, and snow their enemies. Buildings develop cracks, and water seepage causes paint to peel, requiring walls to be resurfaced. Buildings are demolished. New construction obscures murals on walls facing vacant lots and community gardens. Many of New York City’s early murals—and, indeed, many later ones as well—are known today only through contemporary documentation. While most community murals have been documented in some form, their images and the stories behind them have never before been gathered together in one place. On the Wall offers readers the opportunity to explore the variety and richness of these remarkable works of art and to meet the artists, arts organizations, and communities that collaborate to create the murals.

Community murals are hardly unique to New York City. It is generally accepted that the contemporary national community mural movement began in Chicago—an article in Ebony magazine brought widespread attention to the 1967 Wall of Respect—but artists were also painting murals in Detroit, Boston, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. In New York City, community murals first appeared in 1968 in East Harlem, in the South Bronx, and on the Lower East Side. Playing a significant role in the history of the national community mural movement, New York City is responsible for a number of firsts. New York artists developed the projected silhouette mural technique, creating a style that characterized the city’s earliest walls. In 1976, these artists also organized the first National Murals Conference, a gathering of more than 150 mural professionals. And spray artists in the Bronx first collaborated with neighborhood groups to create community murals using aerosol paint.

Many factors influence the creation of community murals: practical considerations, the political climate of the time, the intentions of the various participants, and a willingness to work toward consensus. Among the practical considerations, the current availability of walls and the ability to contract for expensive scaffolds determine mural location, size, and orientation (vertical or horizontal). Social and political considerations give murals their themes and content as well as their evocative titles: Arise From Oppression (Multi-Ethnic Mural) (1972), Urban Rebirth (1975), Pride and Joy* (1982), Push Crack Back (1986), West Harlem Wishes (1993), Erase the Hate* (1996), Nuestro Barrio (1998), and When Women Pursue Justice* (2005). (An asterisk after a mural title indicates that the mural existed in whole or in part as of January 2008.)

(c) Artmakers Inc., When Women Pursue Justice, 2005, Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, photo (c) Jane Weissman.

Community murals reflect the mood and hopes of local residents. They call attention to neighborhood concerns and, chronicling cooperative efforts to address problems, convey the pride of communal accomplishment. They express cultural identification and group solidarity, commemorate historical events, speak to ethnic and racial pride, and honor local and national heroes.

Throughout New York’s mural history, several themes continually recur—most notably, the lack of decent and affordable housing. This problem is directly affected and often exacerbated by the city’s fluctuating financial health, economic policies, and local politics. Murals today still present critical views of gentrification, homelessness, slum landlords, and the failure of local government to address these issues adequately. Community murals continually bring attention to the need for social justice, better education and health care, and improved community-police relations. From the 1970s to the present, murals have offered images of residents demonstrating, raised fists, and picket signs that define and demand solutions to pressing problems. The “community” is also shown actively intervening to rectify prevalent adverse conditions.

For many of those involved, the act of painting a community mural is itself a political act. What propels a neighborhood group to put forward its message to the larger community? And who determines how that message will be conveyed, what the mural will look like? National and international events dominating newspaper headlines rarely find their way into community murals unless the sponsoring organization exists specifically to address such issues (e.g., war, arms proliferation, women’s rights). Artists working with neighborhood groups quickly learn that their members usually hold differing and often polarizing views. National and international concerns become subjects of community murals only when issues have local ramifications on, for example, housing, health care, or the environment and when members agree on a course of action. Essential to the development and success of community murals is consensus on mural themes and content.

Heriverto "Eddie" Alicea, Building the Community, 1980, Harlem, Manhattan, (c) CITYarts, Inc., photo (c) Heriverto "Eddie" Alicea.

In his afterword to Toward a People’s Art (1998), Timothy W. Drescher writes, “In their democratic aspects, community murals may be an ideal microcosm of the larger society, one in which the result is an expression of mutual respect and commonality.” Artists, neighborhood groups, local residents, and sponsors (i.e., mural, arts, or community-based organizations), make up that “larger society.” Each should be present in the development of community murals, equal participants in public meetings and forums where mural themes and designs are determined and/or reviewed. These constituencies inevitably bring distinct interests and goals to the project. Political perspectives often diverge, but sufficient overlap is required to arrive at community consensus.

Neighborhood groups naturally concentrate on pressing local concerns, identifying immediate or long-term goals. Artists, especially those with backgrounds in political activism, see murals as a way to bring attention to the wrongs around them and may filter these goals through a more global perspective. Sponsoring organizations such as local or economic development corporations, which often fund murals, consider their participation in community murals as positive civic engagement and, with notable exceptions, are generally less involved in determining a mural’s theme. The opinions of neighbors who live near a mural can never be underestimated, and ideally they too join in the consensus, sharing the belief that a mural will be an effective vehicle for community improvement.

Joe Matunis, Ashes to Ashes, 2000, Williamsburg, Brooklyn, (c) Los Muralistas de El Puente, photo (c) Joe Matunis.

Neighborhood groups often initiate the idea of a community mural, but they must do more than express such a desire. Guided by their partnering artists, they also articulate whether the mural will address social and political issues or celebrate a neighborhood, its history, and its residents. While a mural organization usually but not always selects the artist, it is the community group that identifies themes, suggests or specifies imagery, reviews the design, and in some cases has final approval of the completed drawings. The group also provides labor and assistance to the muralist in a variety of ways that may range from erecting the scaffold to scraping peeling paint. And almost always, members of the community celebrate the mural’s completion with a dedication ceremony and festivities. It is this interaction among artists, sponsors, and neighborhood residents that makes New York’s community murals eloquent expressions of the city’s enduring, block-by-block sense of identity and anchors them in the life of the neighborhood for years to come.

For a muralist, the magic starts with the wall, which can exert a powerful attraction. For most people, a wall encloses, protects, confines, defends, circumscribes, safeguards, and restricts. To a muralist, however, a wall is a potential painting surface that presents limitless possibilities. Each wall has its own personality, and every artist must take its measure before determining if it is suitable for a mural. The muralist’s romance with a particular wall may be nothing more than a personal fantasy, often punctured when building owners withhold permission or further investigation reveals that a building is slated for sale, renovation, or demolition. A wall may meet all of the artist’s physical criteria yet not be the right choice for a community mural. In reality, the group sponsoring a project usually has a site in mind. Even if that wall has imperfections—doors, windows, patches of tar, crumbling brick—the muralist has no choice but to embrace it.

The artist accepts that the mural design is open to discussion and change until the community’s final approval of the drawings. Ideally, the community also accepts that no fundamental changes will be made to the design after its approval. This does not mean that the artist-community dialogue shuts down. On the contrary; leaving the solitary and protective environment of the studio for the exposed, unpredictable public arena of the street, muralists are thrust into daily contact with residents and workers, a large number of whom opt to join the conversation. On the wall, artists act as the sponsoring organization’s representative to the community at large and must be prepared for questions from passersby. No matter their motivations, they observe, question, critique, and on occasion influence the artistic process. This dialogue is often as powerful as the visual content of the finished mural.

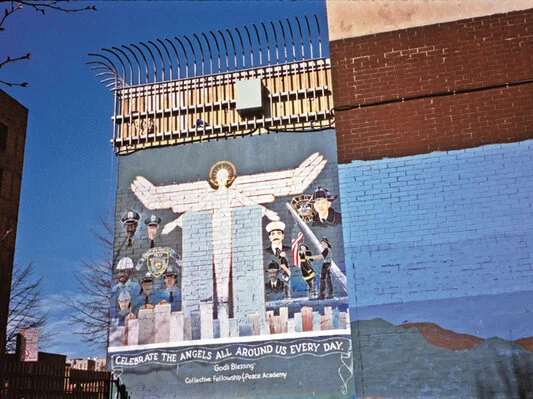

Willard Whitlock, Celebrate the Angels All Around Us Every Day, 2002, Crown Heights, Brooklyn, (c) Crown Heights Youth Collective, photo (c) Janet Braun-Reinitz.

The completion of a mural is a notable moment in neighborhood life. The mural’s success depends on the participants’ experience in the collaborative process as much as its value as a work of public art. For the community, these murals—as long as they last—lend stature to their surroundings and are a continuing source of pride.

A bittersweet understanding accompanies the phrase as long as they last. Very few murals from the early 1970s and 1980s have survived, and many more recent ones from the 1990s and 2000s no longer exist. Community murals are, by their very nature, a temporary art form. Despite the knowledge that their work has a limited lifespan, muralists continue to paint. Philosophically accepting that murals can have brief lives, many artists are still brokenhearted to learn that their walls have deteriorated, been vandalized, or painted over. Some muralists simply move on, not wanting to know of the peeling, fading, and “tagging” that occur over time. Others regularly visit their murals to check their condition and touch up damaged areas. As time passes, neighborhoods as well as community concerns inevitably change. Even when community murals no longer retain their initial power and the motivation for their creation is unknown or resolved, they remain vibrant threads in the daily fabric of neighborhood life.

Janet Braun Reinitz, a painter and community muralist, and Jane Weissman, a writer and public relations specialist, are longtime members of Artmakers Inc., an artist-run, politically oriented community mural organization that works in collaboration with neighborhood groups to create high quality public art addressing residents’ lives and concerns. They are also the co-authors of ”Community, Consensus, and the Protest Mural” (Public Art Review, Fall 2005). Braun-Reinitz, president of Artmakers, is co-author with Rochelle Shicoff of The Mural Book: A Practical Guide for Educators. Weissman, a participating artist and project director of several Artmakers murals, is the curator of the traveling exhibition Images of the African Diaspora in New York City Community Murals, developed to coincide with the publication of On the Wall.