"Out of ashes comes beauty": An interview with Jeffrey C. Stewart

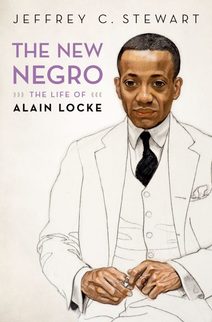

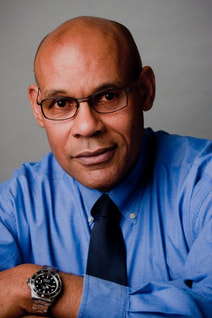

Today on Gotham, Peter-Christian Aigner speaks with Jeffrey C. Stewart about his new book, The New Negro: The Life of Alain Locke, the most comprehensive biography on the "father of the Harlem Renaissance."

You began this project long ago, before there was any monographs or collected scholarship on Locke's work and life. So what first prompted you to write about him? Was he still remembered? Did he feel especially relevant somehow against the political or cultural backdrop of the 1960's and '70s? Has that changed in any way since you began?

I was drawn to Alain Locke initially because I was curious how a philosopher would engage the questions of race and identity in America of the 1920s especially considering such issues still persisted in the 1960s and 1970s. I knew nothing about him until John Blassingame, who had studied at Howard University where Locke taught, brought his story to my attention. I had majored in philosophy as an undergraduate at UC Santa Cruz with phenomenologists and existentialists, and at Yale I was introduced to pragmatism and cultural pluralism, subjects that Locke had not only studied but pioneered. My deepest interest was to find a way to balance the demand for a post-racist American society with the felt necessity in the 1960s and 1970s for Blacks to assert a distinctive identity to survive in an America refusing to embrace that post-racist future. What I found interesting about Locke is that, while he can be credited with creating identity politics with his conception of the New Negro in the 1920s, he demanded, like Aristotle, that something higher and transcendent be our larger goal. A sense of racial identity was crucial to the Black community but at the same time it was not enough — there was also something more, something larger, collective and universal that could come out of racial identity that leads us to a richer and more honest universalism, which he called cultural pluralism, than traditional narratives of Western Civilization offer. Today, as a nation, we are still struggling to accept cultural pluralism as Americanism, still trying to accept the right to difference as an American right, and America as something more than a single script.

Locke becomes the first African-American to get a Rhodes scholarship, but encounters plenty of discrimination at Oxford. While there, soaking up European art, literature, and music, he is lecturing on the limits of cosmopolitanism, and has something of an intellectual turning point when he attends the Universal Races Congress. Can you speak about that?

All heroic stories, as Joseph Campbell taught us, contain a life crisis that reveals to the hero his or her quest. Locke was on the path to become just another early twentieth century American aesthete when he went to England in 1907 as the first African American Rhodes Scholar and encountered the fierce relentless antagonism of Southern Rhodes Scholars who felt his presence among them was a scandal. They did everything they could to make his life miserable and even succeeded in getting the Rhodes Trust officials to exclude him from the annual Thanksgiving dinner all Americans attended in Oxford. Deeply hurt, he quietly attended an alternative Thanksgiving dinner of those Americans who protested his treatment, especially with Horace Kallen, the Jewish graduate student in philosophy he had met at Harvard. There ensued a long discussion between the two of them about the necessity of racial identification for minorities and led to the formation of the concept of cultural pluralism, that ethnic groups have a right to their own cultural heritage and identity even as they assimilate politically into Americanism. But Locke's encounter with racism hurt him in ways he could not recover from. Eventually, he was sent down from Oxford without a degree. Marooned in London and penniless, staying with his friend, the Sri Lankan aesthete, Lionel de Fonseka, Locke attended the Universal Races Congress and found a slew of intellectuals like Franz Boas, Israel Zangwill, von Luschan, Fouilee, speaking at the Congress who were redefining race theory for the 20th century. And through listening to their presentations,he came up with the formulation that race is not a biological but an historical phenomenon, that being Black is not a destiny but a history that can be used to create whatever destiny you wish. That laid the sociological ground for his later advocacy of the New Negro aesthetically in the 1920s. In a sense, encountering racism at Oxford convinced him that he had to devote his intellectual wealth to the race struggle, a struggle to liberate the minds of Americans from the nightmare of their denigration of their fellow Americans because of race.

At one point, you draw a parallel in the way Lenin sees the outbreak of World War, as the last stage of capitalism, and the way Locke views it, as driven by the racial dynamics of imperialism, which Marxists largely ignored. But he's also dismissive of black nationalists and socialists. Why?

Locke saw race as Marx saw class, as the pivot of history, and a vortex of human relationships that once understood made plain why we are in the predicament of race we now live in. Lenin is important because he analyzed what is called the "highest stage of capitalism," which is imperialism. Locke understood the race situation in the United States as a form of imperialism, of domination of one group or nation over another, backed by the economic power in the hands of one racial group, and extended around the world. Locke is really the first example we have of what will become commonplace in the 1960s — the use of colonialism to understand the American race problem. But in terms of political style and public presence, Locke was not a radical yelling on soapboxes in Harlem or spending years in union halls trying to get the white working class to accept black workers. He was a closet Marxist but also a skeptic of protest and revolution, because he saw protest as reductive, as narrowing the Black experience to simply a reaction to racism, and making the Negro cause dependent on the white subject. Rather, he wanted to use art, Black creativity, interiority, and Black loveliness to create an agency in Black people to heal and propel themselves forward. In that sense, he has affinities with someone like Malcolm X, who argued in his nationalist phase that the Black people should heal themselves and not be too dependent on White assistance. The irony, of course, is that his entire project of the Harlem Renaissance was heavily dependent on White support, from Paul Kellogg, the editor of Survey Graphic to Charlotte Mason, the patron who gave him the money to support the research and writings of Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes, and Richmond Barthé, among other. In that sense, Locke’s story is a manual of the predicament of the Black intellectual in America, with lessons for anyone who wants to know what is required in terms of relentlessness to make a difference in the lives of Black people when there is no revolutionary situation afoot, as their was in Lenin’s Russia.

You suggest in the opening to your book that Locke avoided these groups also because of the Victorian heterosexual culture of the bourgeoisie. Cultivating a movement of black art, then, is his chance to make a community safe for gay men like himself, and to become a public intellectual, without exposing his identity?

Locke reacted against the bourgeois establishment in the NAACP and the Urban League of the 1910s and 1920s for two reasons. One, he felt that they were too wedded to protest and protest would never convert racists from their racism, since, as his theory, recorded in Race Contacts suggested, racism served the economic and political interests of racists. This idea would later be explored relentlessly in W.E.B. Du Bois's Black Reconstruction. Second, I argue there was a culture of bourgeois heterosexuality in such organizations that excluded him. He could never fit in. So, yes, he created an alternative world in the Harlem Renaissance that was tolerant of Black homosexuals in part because much of the art created came from gay or lesbian or sexually ambiguous writers. It was not a separate community, but a Black community that thrived in places like Harlem, at bars like Smalls, where people could come together and love and live without having a repressive Victorian hounding them.

There are lots of figures in the Harlem Renaissance who are queer, and later examples of important black historical figures denied their place in the sun because of their homosexuality (Bayard Rustin is probably the most notorious example). But Locke's politics are not strictly about protecting his sexual identity, right? You make that clear in the section on the Harlem riot, for example, and where you talk about his views on Booker T. Washington, early on.

Locke is an example of intersectionality, although applied in a way different than usual. Rather than Black and female, his intersectionality is Black male and Queer, and that convergence of identities and experiences becomes something new — a kind of third identity that he tried to outline in some of his private notes. In that third space, race was crucial because on some level he saw it as foundational of the American project, as a serpentine cancer that killed all other chances for beauty that it encountered. At the same time, in his ruminating on this intersectionality, Locke argued that he had been marginalized because he was Black, homosexual, and small — and he could have added disabled, as he was also hobbled with a heart ailment from childhood rheumatic fever throughout his life. But here's the kicker: he refused to accept a victimization narrative about himself for any of those identities, qualities. Rather, he consistently sought to turn them into advantages. He refused to lick his wounds because he was marginalized by difference. Rather, Locke also saw opportunity that race offered him that was completely absent for him in becoming a gay leader in the 1920s. By building institutions on the basis of race advocacy, he created spaces for his gay identity and that of others like him; and he flourished because of that creativity, despite his exclusion from the traditional race leadership posts in the NAACP, the Urban League. His is an incredible story of agency and personal creativity through institutional improvisation and pragmatism, that launched such institutions as the Bronze Booklets, a scholarly publishing house, that he ran from his post office box in Washington, DC. That intersectionality gave him a special sense of mission and energy that made him unique among the prominent Black intellectuals of his time. He believed that third space he occupied was a space of power.

Locke's historical shorthand, as 'dean' or 'father' of the Harlem Renaissance, has always been somewhat odd, because he lived mostly in Washington, DC, during the '20s, and was not even a minor published writer before editing the work that established him as that movement's leader. What in particular did New York City offer him, and the others who made up that community?

New York was always the city Locke was trying to get to — whether on weekends or permanently as when he sought a job at NYU after James Weldon Johnson died. New York was a mecca for him both as the one place in America that seemed to him to value writers and artists, that took literature seriously, and offered the opportunities for African Americans to be artists. There was something about the energy of the streets in New York and Berlin that captivated Locke, as he was a boulevard guy, someone who liked to walk and stroll, engage people on the street, be recognized, and feel alive on the street. New York, therefore, was a discursive space, a sign of the Black modernism, and the influence of Black creatives in forming American modernism, rather than simply a place to live and reside. Of course, eventually he moved New York in the late 1940s, but moved to Greenwich Village rather than Harlem, a sign, I believe, that towards the end of his life he had the means to own a home in a community that accepted his sexual identity. Greenwich Village was also incredibly alive with the art world of New York in the 40s and 50s, with the advent of abstract expressions, bebop jazz, coffeehouses, nightclubs, etc. Locke loved being around all of that energy as a man of the city, and New York and Berlin offered that nightlife that he very much loved. New York offered Locke and other queer intellectuals of the Harlem Renaissance the most important of values — freedom.

You write that New York, like Berlin, was an incredible site of liberation for Locke, sexually. And there are lots of little stories in your book about the Harlem Renaissance men he grooms and pursues. But there's another story here, too, sexually, no, about his efforts to marginalize the women in that movement, like Zora Neal Hurston?

There's a cautionary tale here. Locke's not so hidden source of creativity was his love of younger men, primarily artists he courted, promoted, and sought affairs with. This is a story of the creative power of sex or in its absence desire. Love is generative. But in Locke's case, an overwhelming focus on men as the object of desire and intellectual awakening meant that he did not see women as the source of generative creativity he found in men. For example, Locke met Zora Neale Hurston when she was a student at Howard University through some of the student humanities institutions he created, the Howard Players being one of them. Eventually, he was so impressed with her writing that he secured a white patron, Mrs. Osgood Mason, for her, along with Hughes, and provided her with a stream of financial help in the late 1920s and early 1930s. He even took her side in her battle later with Hughes over the authorship of their shared play, Mulebone. He believed she was a genius.

But Locke never gave Hurston the kind of unqualified support that he gave Hughes or other Black male writers. In 1928, she asked him to accompany her on a folk culture-collecting trip through the South. Of course, the image of Locke, whom David Levering Lewis called the Marcel Proust of Lenox Avenue, walking through gin joints and turpentine camps in the South with Zora is hysterical and highly unlikely. He turned her down, not surprisingly. He was deathly afraid of violent southern racism. But if it had been Hughes, Locke probably would have gone, and if he had gone with Zora he would have grown more in his understanding of Black folk culture, as an analogous formation of self-healing to his high culture, that would have deepened him profoundly as a critic of African American art and culture. And his support of her institutionally would have meant that she might not have had to suffer as much as she did in later life when there was no Mason money coming and she was bereft of a post as a teacher like others.

To be fair, one has to admit that Locke was like most innovators: he could not carry the revolution to its logical conclusion. Locke had revised the notion of Black masculinity in the New Negro away from its heteronormativity. That was about all of the heavy lifting he was capable of in the area of gender politics.

At 878 pages, this book feels and reads like a passionate brief to remember a largely forgotten figure — who, as you say on the last page, never wrote anything of "lasting" literary value. You make a case for his philosophical contributions at times, but end with a very eloquent summary of his "gift" to African-Americans — the concept, taken from his essay, which forms the title of your book. What is that gift?

I think the length of the book conveys the seriousness of the undertaking. I see the book as a life and times biography — a fierce contextualization of one man's life so that the reader is awakened to the founding debates of African American intellectual life as hidden from public discourse as Locke himself. That's my gift, for whatever it's worth — the gift of a complete portrait of the life of the mind in America shot through the lens of a Black queer man. At a time when there seems to be an obsession in brevity of information transfers, I am resisting the attempt to truncate telling the life of an extraordinary man. What is Locke's gift: the gift to us to see the artist and the art of the Black experience as a liberating pair — an unseen way to bridge the racial divide and energize the Black creatives to feel their art has a larger, conversation-changing social purpose. Locke was the first intellectual to make us aware of the spectacular accomplishment of Black culture in America, which yielded amazing innovations in music and art, out of an experience of America that Eleanor Traylor calls the experience of "rootlessness.” Locke made us see something that is still under-acknowledged today, that the American who most lacked the benefits of Americanism has created the most distinctive forms of culture that define American culture. How he did that with little or no support from institutional civil rights organizations of his time is an amazing story I wanted to do justice to.

Often people ding Locke for not writing a major literary work: but what he did is eminently more important: he supplied the intellectual context for Black literature, art, music, theater, and film to be appreciated as probative and meaningful. He explained to an eager Black audience and a curious White one why Black literature mattered, and what it had to contribute to the American, let alone African American struggle, for dignity and distinction. In the West, it is not enough simply to create art — one must create a critical rationale for what that art means, how it changes the way we see our world, and why art matters in an overwhelmingly materialistic America. This is what Ezra Pound did for literary modernism before he wrote the Cantos. Critics are crucial to how we learn what is important about our culture and ourselves. Before Locke, there was no sustained critical discussion, for example, of African American visual artists. He created through essays, articles, and exhibitions a rationale for why they had something distinctive even revolutionary to contribute to the art world. What's compelling about Locke is that he had to work his way to this position out of the self-hate and self-denigration of Blackness that he was brought up with as a Black Victorian. Locke was brought up to hate the culture of Black folk; but through a series of metamorphoses learned to appreciate the value of African and "Afro-American" art as a resource for all Americans, but especially African Americans who even today are often aught to flee themselves and their culture because of the hell they experience in the streets. The takeaway from this story is out of ashes comes beauty, and his recommendation to us to choose the beauty over the ashes of the American experience. That is an encouragement we need as much today as it was needed in the 1920s.