Paul Rudolph: Would-be Savior of Robert Moses's Lost Highway Dream

By Sam Lubell and Greg Goldin

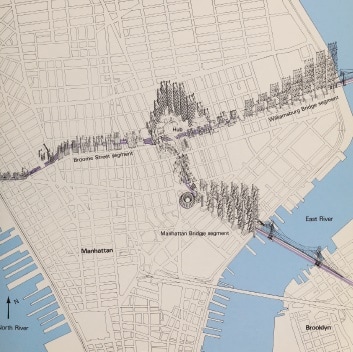

In 1967, Paul Rudolph was asked by the Ford Foundation to reimagine Robert Moses’s maligned but not yet dead Lower Manhattan Expressway (LOMEX), a Y-shaped link that would have connected the Williamsburg and Manhattan bridges to each other and to the Holland Tunnel. Opponents, led by activist and author Jane Jacobs, eventually killed the project (it was scrapped officially in 1971), saying that, in the name of urban renewal, it would eviscerate the neighborhood and ransack its residents.

This is the sixth in a series of posts drawn from the authors'recent work

Never Built New York, published courtesy of Metropolis Books.

“A conventional urban expressway might very well be more abusive to the city,” Rudolph demurred. “On the other hand, building a new type of urban corridor designed in relation to the city districts through which it passes and engineered in such a way as to be capable of dissolving traffic and diminishing noise, exhaust, environmental and surface-street problems that have plagued the corridor area for decades might just be the most desirable approach.”

Rudolph believed he could save the highway by burying it. Rather than demolish hundreds of buildings, ripping apart what today is SoHo and Tribeca and dividing Manhattan in two, he drew plans for one long megastructure, covering the roadway from the Hudson to the East River. Rudolph’s notion was to preserve the fine cast-iron facades along Broome and Spring streets, and to keep intact the great majority of buildings on the Bowery––and on Chrystie and Delancey streets––by running the expressway below grade in the backyards behind existing structures.

His scheme would conform to the architectural topography of the existing streets, forming undulating hills and valleys. Where the architectural landscape called for height––such as at the mouths of the bridges––Rudolph sketched height. Where the streetscape was low lying, his new buildings were low lying. Like Hugh Ferriss in his book The Metropolis of Tomorrow (1929), Rudolph pictured Lower Manhattan as basin and range, lithic outcroppings cut through with multiple bridges and terraces, a monorail, and pedestrian tubes, perched above the submerged highway.

Rudolph placed 60-story towers on the approaches to the bridges, creating gargantuan ramparts he described as gateways to the city. These buildings, all made from prefabricated modular units––which he called twentieth-century bricks––cascaded down to 12 stories the deeper they got onto the island, eventually becoming tentlike, A-frame canopies covering the sunken roadway. His precast-concrete modules were meant to be 12 feet wide, 11 feet high, and 60 feet long. Delivered by truck, they could be assembled into innumerable shapes, resembling a Russian Constructivist dream or a Wyoming Grand Teton. The modules, perilously suspended from a lattice of stanchions, climbed on the diagonal, creating sloped pods high above open-air plazas.

The strategic core of Rudolph’s vision was the HUB, a cluster of nine-story buildings that tied together every type of transportation––from subway to pedestrian walkway to expressway–– with all forms of city life. Like a three-dimensional plaza,most of the civic, cultural, or productive energy of the city would be enacted across various levels and at differing scales. “A complex of connected buildings and spaces on a very large scale that can be used conveniently and easily by people” is how Rudolph described the circular, multilevel buildings. “People movers,” whose promise of connectivity Rudolph heartily embraced, slipped easily in and out of the towers.

Boldly immodest, Rudolph was proposing to save the city by intensifying it in a manner far greater than anything Moses conceived for the LOMEX. Certainly, Rudolph’s new city would, to a terrifying degree, enshrine the automobile while entombing the streets. But the true merit of his plan lay in his conception of the city as a sinew of buildings, bridges, terraces, plazas, overlooks, walkways, people movers, subways, streets, and freeways, all drawn together into one exquisite whole. He described it as “a single complex physical system placed within the urban space.” Like an enormous opera set on an even larger baroque stage, his singular creation was a mighty spectacle “revealed to...the person of the city.”

Rudolph and his model builder, Donald Luckenbill, worked on a mock-up of City Corridor in a downtown studio for five years. In the end, Rudolph’s plan was realized only as a set of magnificent drawings of a fictitious city––a dense, animated skyline that upends nearly every other modernist city planning proposal, before or since.

Sam Lubell is a Staff Writer at Wired and a Contributing Editor at the Architect’s Newspaper. He has written seven books about architecture, published widely, and curated Never Built Los Angeles and Shelter: Rethinking How We Live in Los Angeles at the A+D Architecture and Design Museum. Greg Goldin was the architecture critic at Los Angeles Magazine from 1999 to 2011, and co-curator, and co-author, of Never Built Los Angeles. His writing has appeared in The Los Angeles Times, Architectural Record, The Architect’s Newspaper, and Zocalo, among many others.