Piccola Stella Senza Cielo

By: Dondiego Nunziata

Napolitans Waiting to Leave the Harbor of Napoli, circa 1900

I’ve begun my discussion on my blog focusing on the history that led up to the mass exodus of Napolitans and Sicilians, from their homelands, to the four corners of the globe over a hundred years ago. Many of us who read these histories do so in a language different from that of our ancestors, who last laid eyes on our beautiful motherland. Forced to flee by the advances of an invading army; forced to flee from the repression cast down upon them from a foreign legion; forced to flee the rape, murder and thievery of their culture, and of everything they held dear –- our ancestors faced an even more daunting challenge once their decision to leave their fallen Kingdom became the reality of their new lives. Here’s one experience, of the millions of exiled Napolitans and Sicilians, once they arrived on the shores of their new countries, many of which were just as unfriendly as the homeland they left behind.

San Fele, Basilicata Today

The truth of the matter is, America was a very hostile place for most immigrants, but especially for those who didn’t speak English, and for those who were Roman Catholic. As Napolitans, our ancestors were both. And for many of them, like 13-year-old Carmela Pietropinto, the arduous journey itself began a period of twelve years in her life that must have felt like hell on earth.

As a schoolteacher by trade, I get to witness first hand the trials and tribulations of the teenage set. Thirteen-year-old girls and boys, easily molded by their early experiences, come in and out of my life each year, and I know that what they experience and learn during this crucial time in their lives has an impact that exceeds no other. The trials these children face, however – even the worst and most heartbreaking ones – pale in comparison to what young Carmela had to endure as she journeyed to America and beyond.

It began by saying goodbye, to her entire family, in the tiny Lucanian village of San Fele…

Pontelandofo then and now

Carmela’s father Francesco set up a nice life for his young family in San Fele – or so he thought. As a medical doctor, Francesco Pietropinto was a successful man, but with the advances of the Piedmontese army he had seen his paying customers dwindle down to zero. Being in a remote Lucanian outpost also meant that he was probably servicing many of the briganti who were desperately fighting the occupying Piedmontese for their lost freedom. As a result, this left these villages, if they were ever reached by Piedmontese forces, as prime targets for angry Northern soldiers seeking vengence. Because of this, Francesco decided to pick up and move his entire family to New York City, where a large number of San Felese, including Carmela’s future husband, had already set up shop. Simply living in and being from a place like San Fele meant you were taking a chance that what had happened in the villages of Pontelandofo and Casalduni, could happen to you.

“No stone should remain standing,” was the Piedmontese order given at Pontelandofo. The town’s most beautiful woman – or at least whom we think was the most beautiful woman, because all of the invading Piedmontese took their turn with her – Maria Izzo, was tied to a tree naked, her legs raised in the air, and repeatedly raped until the last soldier finished with her. That soldier then forced his bayonet into her belly, leaving her to bleed out. We can now see why it was of the utmost importance for Francesco, our last King’s namesake, to get his family out of Lucania. Even though the massacres at Casalundi and Pontelandofo occurred thirty years prior, the prevailing attitude and oppression remained – and still remains today throughout the South.

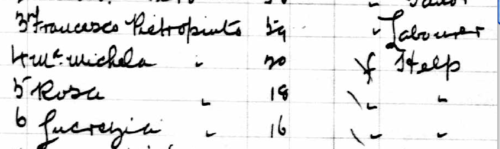

Francesco Pietropinto, Carmela’s father, and her three older sisters, clearly labeled “HELP” in their occupation column, filling us in to what Francesco expected of his children in America, to work.

Despite being a medical professional, Francesco wasn’t able to secure passage to America together. He was able to find four tickets. One for himself, and three for his eldest daughters: Maria Michela, 20; Rosa, 18; and Lucrezia 16. This left his youngest daughter, Carmela, to take an earlier ship arriving in New York fifteen days before the rest of the family – alone. Traveling on the Karamania by herself, Carmela endured the painful journey away from the only home she’d ever known, in solitude. When she arrived on the shores of a land whose language she did not speak or understand, she was left to do so alone. Alone, she waited for 15 days, before her sisters and father arrived on board the Algeria on August 15, 1896.

Carmela, found on line 151, aboard the Karamania arriving at Ellis Island Aug. 1, 1896. Note she has no relatives around her, and after a search of the entire manifest, none could be found.

Once she arrived, things didn’t get any easier. As you can see from the first ship manifest of the Algeria, which arrived at Ellis Island on August 16, 1896, Francesco expected each of his children, for whose migration he had paid, to chip in and work to help pay the rent at their tenement house apartment at 210 East 59th Street.

According to Francesco’s death certificate, once he arrived, this once proud medical doctor from San Fele, was only able to secure himself a job as a veterinarian in New York City. Most likely, his language and status as an immigrant prevented him from obtaining a medical license in New York at the time. But before succumbing to heart disease in 1905, Francesco managed to become the catalyst in an extremely heart-breaking, but unfortunately all-to-common, narrative — the narrative many Napolitans and Sicilians shared once they arrived here in the “land of the free”…

Death Certificate of Francesco Pietropinto, NYC January 13, 1905

When Carmela’s father arrived two weeks after her debarking from the Karamania alone, it was a reunion not too difficult to imagine. Father and daughter, separated for two weeks, most likely longer than they had ever been apart before then, this time in a new world, again felt each others’ warm embrace. It was a world where the language was unknown, and the culture even more foreign. It was a place where the realities of city life set in quickly for the rural family who knew nothing else. In order to feed and house his family, Francesco needed his family. He needed them more than ever. And he needed them to work.

Carmela though, was a fourteen-year-old girl. And for those who have not had the pleasure, fourteen-year-olds are not the most easily convinced once they get their heads wrapped around an idea. I have a daughter of my own, and everyday I fear the future, that one day she will be fourteen. One day she will think she knows best, and I will know I’m done for. That day came for Francesco when his daughter Carmela refused to take work in the bustling city of Manhattan in August of 1896. To Francesco, he had no choice.

It may seem cold and calculated, but knowing what I know of Napolitans, it was necessary. Francesco gave his youngest daughter a choice: work and help support the family and herself, or go. Carmela refused to work. Perhaps it was the two weeks she spent in Manhattan with her fellow San Felese emigres. Perhaps it was the false freedom that America promised, and still promises its people, new and old alike, today. But something told Carmela to refuse her father’s demands to work and earn, and instead make a demand of her own, a demand to learn and go to school.

She perhaps had read about the work of brave women like Susan B. Anthony, and realized that for her future she needed to learn. She already knew how to read and write Lucanian, but here in America, that wouldn’t get her far past Mulberry St. She wanted to learn English and go to school. Instead of dropping her off at school, though, her father dropped her off at an orphanage for young girls in Rockaway, Queens. Today, only St. John’s Home for Boys remains near the beaches off the Atlantic, but at the turn of the century orphanages and alms houses were a necessary part of New York and American Society, and the Rockaways housed many. Like many immigrants to this new land, Francesco had to make a heart-breaking decision: keep his daughter and risk starvation, or give her up, and know she’ll be fed and educated and perhaps have a chance at a better life. In reality, he had no choice. He had to say goodbye to his little star.

Carmela was his little star. She was always different, and always felt she had been destined to do something great with her life. But with conditions in Naples deteriorating as each year passed since 1860 and the fall of the Due Sicilie, the Pietropintos knew that their destiny wouldn’t be fulfilled there. So they looked across an ocean, to New York, as millions of other Napolitans did after “unification”. So for the moment, she was a little star without a sky, ready to burst, and burst she did, in a flaming ball of raw emotion, as she said good-bye one last time to her family, and to her father.

After this latest exile, she cut off all ties to her family, and took to heart the message given to her from the Protestant Orphanage where she lived until she turned eighteen. However, in doing so, she lost a connection to her homeland, her Catholicism, and her parents. Even though a reunion did take place with her mother after her father’s death, things were never quite the same and the distance was clear even to Carmela’s children.

She eventually did find love and a family, when she met and married fellow San Felese Leonardo Dondiego, a successful barber and business owner from Sullivan Street. They were married in 1907, on September 1, and a year later had their first child, a daughter, Rose. A year and a half later, their first son Vito was born. By 1911 they had moved to Brooklyn, and had three more sons, and two more daughters. In 1912 Frankie was born, 1914 Joseph arrived, followed by Leonard in 1916, Margaret in 1917, and Vivian, my grandmother, in 1919. And from July 6, 1928, she did so again, alone. Her husband Leonardo, died of a heart attack while shaving a man in his Coney Island barber shop after years of working seven days a week.

http://archiver.rootsweb.ancestry.com/th/read/NYBROOKLYN/2002-10/1033961380

Her star may not have been realized in a very public life, but she managed to raise seven successful children. Two became veterans of the Second World War, serving the United States honorably in Europe, helping to defeat the Nazis and free Western Europe. One son went on to become a Medical Doctor, fulfilling the intellectual promise first set forth by her father, and another became a New York City Police Officer who served his home community of Coney Island for almost fifty years.

Carmela eventually died in October of 1949, but she laid the foundation for a star bright future in our temporary country of residence. Carmela’s grandchildren and great-grandchildren include lawyers, educators, writers, and stage performers who all carry on her pride, her work ethos, and her spirit of individuality. It would appear that, even though her star was nearly extinguished on a cold August day in 1896, it’s shining today as bright as ever.

I hope that Carmela’s spirit is carried into the next century, and perhaps even back to a repatriated homeland, by my daughter, Carmela’s great-great grand daughter and my own personal “piccola stella.”

Dondiego Nunziata is a fourth generation Neapolitan-American living in Brooklyn, New York with his wife and two children. The focus of his blog, Where Have You Gone Joe DiMaggio?, is to highlight the forgotten culture of so many Neapolitan-American and Sicilian-American families who mistakenly identify themselves as “Italian” and to begin a journey to regain self-determination for a region of Europe that for all but the last 150 years was one of the most successful and productive in human history.