Pulitzer Remembered as a Man of Peace Not of War

By James McGrath Morris

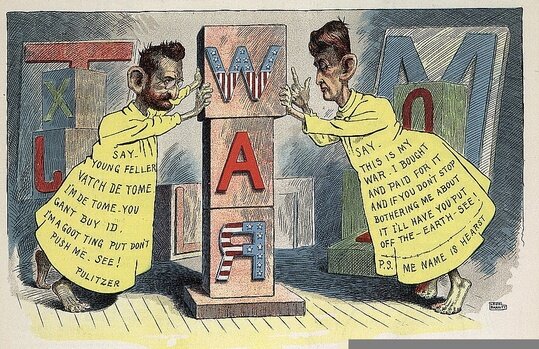

Sitting in the shadow of the New York Plaza Hotel, the nearly nude bronze sculpture of Pomona by Karl Bitter atop a six-level water fountain is a graceful work that at night, bathed in golden light, is a serene and peaceful oasis on the southern end of the Grand Army Place at 59th Street and Fifth Avenue. To many New Yorkers who think they know the man, the fact that Joseph Pulitzer made the bequest for this fountain that speaks of peace is strikingly ironic. Wasn’t he after all the worse purveyor of Yellow Journalism who used his perch of power to help rush America to war with Spain in 1898?

No.

That’s why the Pulitzer Fountain is a reminder that we are often too quick to judge. After spending five years working on his life I was, as many biographers are, astounded how often my subject is wrongly portrayed in our history books. In Pulitzer’s case one the biggest misunderstandings is his role in the Spanish-American war. Not that Wikipedia is the paragon of accuracy, but its description of his role is much like those our children read in their textbooks:

Typically accounts of the 1898 war place equal blame on Pulitzer and his rival William Randolph Hearst. Pulitzer and Hearst are often credited (or blamed) for drawing the nation into the Spanish-American War with sensationalist stories or outright lying …Pulitzer, though lacking Hearst’s resources, kept the story on his front page.

The problem with this repeated portrayal is the personalization of the World newspaper that Pulitzer had built into America’s most widely circulated and politically powerful newspaper. True, he owned the entire operation and its politics, style, and vibrancy was a reflection of his personality. But, the fact ignored by most historians is that Pulitzer was not responsible for his paper’s day-to-day conduct during the war. Unlike the younger Hearst at the New York Journal, he did not have his hand on the helm. In the fall of 1897, Pulitzer’s most cherished daughter Lucille died after a prolonged illness. Pulitzer, already depressed by a descent into blindness, retreated to Jekyll Island, a private retreat of the rich and powerful off the coast of Georgia. While there, the USS Maine was blown up in Havana harbor igniting the public’s passion and providing Heart’s Journal with powder keg it wanted to spark a war with Spain. He spared no expenses and rushed to beat the World in real and imagined scoops.

There was an atmosphere of desperation under the gold dome on top of the Pulitzer Building on Park Row, as the publisher remained secluded grieving over Lucille’s death. The staff, from the editors at the top to the reporters on the beat, consisted of men and women whose loyalty ran so deep they had chosen to cast their lot with Pulitzer rather than Hearst. They were willing to do anything for their absent general, and not out of loyalty alone. Everyone knew that Pulitzer was pouring his own money into the paper to make up for the losses induced by Hearst.

For those who remained at the World, losing to Hearst could mean the end to their careers. The staff struggled to match the Journal, but lacked the resources to compete effectively with Hearst. The epic battle did not pit Hearst against Pulitzer. Rather, it was Hearst against Pulitzer’s leaderless troops in a helter-skelter 24-hour-a-day competition. The World was losing its battle with Hearst, and losing badly.

The newspaper that had once set the news agenda for the city, and sometimes for the nation, was engaged in a futile game of catch-up. “It has been beaten on its own dunghill by the Journal, which has bigger type, bigger pictures, bigger war scares, and a bigger bluff,” Town Topics gleefully reported. “If Mr. Pulitzer had his eyesight he would not be content to play second fiddle to the Journal and allow Mr. Hearst to set the tone.”

By the time Pulitzer returned to New York, the battle was lost. From the command post of his house, Pulitzer tried to fix what ailed the World. He reorganized the staff, trying to put in charge editors with the courage to cease imitating Hearst. Confident that he had found a man that would keep the staff in check, Pulitzer turned to the question of the day: should the United States go to war? There was no doubt that the Journal was champing at the bit for war. The Sun said war could not come soon enough. Almost every major metropolitan newspaper favored either war or the threat of one if Spain did not comply with American demands.

Pulitzer joined the chorus. But in doing so he supported the war only as a last resort. He did so not to contradict his support of international arbitration. Pulitzer believed that nations should solve their problems at a table rather than in a battlefield. Three years earlier a similar crisis between the United States and another world power had arisen. How Pulitzer reacted to this event tells us far more about his character and beliefs than his minor role on the sidelines of the Spanish-American War. In 1895, a discovery of gold intensified a quarrel between Venezuela and Great Britain about its border with British Guiana. The United States took Venezuela’s side, broke off diplomatic relations with England in late 1895, and demanded arbitration. The British, who ruled the seas, considered this an insult and refused. The rebuff drew an angry message from the president to Congress. Invoking the Monroe Doctrine, Cleveland promised that if England dared to take any land the United States deemed as belonging to Venezuela, the United States would “resist by every means in its power.”

Congress rushed to the president’s side, and the saber rattling put the little-noticed dispute on the front pages. War on Every Lip was the Chicago Tribune’s headline. War Clouds proclaimed the Atlanta Constitution. The editorial pages clamored for a fight. “Any American citizen who hesitates to uphold the President of the United States is either an alien or a traitor,” said the Sun.

Theodore Roosevelt, then New York City’s Police Commissioner, was thrilled by the prospect of war. He was convinced that the entire nation, not just Manhattan, lacked virility. “There is an unhappy tendency among certain of our cultivated people to lose the great manly virtues, the power to strive and fight and conquer, not only in a time of peace, but on the field of battle,” he told one audience. He thought the time had come for the United States to flex its military muscle outside its borders, and he saw an opportunity in a crisis brewing in Venezuela.

Roosevelt, who had never seen a battlefield, wanted war. Pulitzer, who had, wanted nothing of it.

Pulitzer refused to let the World join in the clamor for war. He thought Cleveland had gone too far. Put the headline A Grave Blunder on the lead editorial, Pulitzer told one of his writers over the telephone from his rented house in Lakewood, New Jersey. Weighing each word carefully, he composed a four-paragraph assault on the president’s logic. Great Britain’s actions in Venezuela posed no danger to the United States, he said. “It is a grave blunder to put this government in its attitude of threatening war unless we mean it and are prepared for it and can hopefully appeal to the sympathizers of the civilized world in making it.”

Pulitzer expanded his efforts to douse the war fever. Over his signature, his staff sent telegrams to leading statesmen, clergymen, politicians, editors, leaders of Parliament, and the royal family in Great Britain, urging them to publicly express their opposition to war. Within days, the World published replies from the prince of Wales, William Gladstone, the bishop of London, the archbishop of Westminster, and dozens of other leaders. Each telegram professed England’s peaceful intentions and strove to lower the transatlantic rhetoric. “They earnestly trust and cannot but believe the present crisis will be arranged in a manner satisfactory to both countries,” read the message from the British throne. “No feelings here but peaceful and brotherly,” wired the bishop of Liverpool. “God Speed you in your patriotic endeavor,” added the bishop of Chester. The World’s issue for Christmas Day 1895 reproduced the telegrams from the prince of Wales and one from the duke of York under the headline Peace and Good Will. Soon, said another of Pulitzer’s editorials, the holly and mistletoe would be gone, as would the voices of children singing carols. “But we shall retain our hopes. The white doves, unseen, will be fluttering somewhere.”

In England, the telegrams sent by the prince and the duke generated considerable support and were on the front page of most newspapers, reported an excited Ballard Smith. The reaction in the United States was quite different. Roosevelt, who had already written a letter of congratulation to Cleveland for his belligerent threats, told Lodge that Americans were weakening in their resolve for war. “Personally, I rather hope the fight will come soon. The clamor of the peace faction has convinced me that this country needs a war.” He was furious at Pulitzer and Edwin Godkin at the New York Post, who had joined in urging restraint. “As for the editors of the Evening Post and World,” Roosevelt said, “it would give me great pleasure to have them put in prison the minute hostilities began.”

Roosevelt didn’t get his chance. Tempers cooled. The dispute between England and Venezuela moved to the back pages as the two nations agreed to arbitration, prompted in great part by Pulitzer’s actions.

Sadly, Pulitzer’s role as a peacemaker in 1895 has been forgotten. Rather the role of his troops as war makers in 1898 lives on. The fountain at 59th and Fifth sits in vigil, a reminder of this lesser known side of the man.