Remembering the Columbia Protest of '68: Faculty

Fifty years ago this week, students at Columbia shut down the university for seven days, in protest of plans to build a gymnasium in a nearby Harlem park, university links to the Vietnam War, and what they saw as Columbia’s generally unresponsive attitude to student concerns.

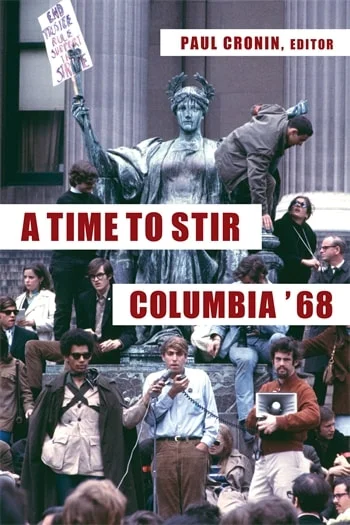

Today on Gotham, we continue a weeklong series featuring excerpts from a new collection of more than sixty essays, edited by Paul Cronin, reflecting on that moment. A Time to Stir reveals clearly the lingering passion and idealism of many strikers. But it also speaks to the complicated legacy of the uprising. If, for some, the events inspired a lifelong dedication to social causes, for others they signaled the beginning of a chaos that would soon engulf the left. Taken together, these reflections move beyond the standard account, presenting a more nuanced Rashoman-like portrait. Yesterday we considered the remembrances of students (male, female, black, white, visiting, resident, pro, anti). Today, we carrying forward the approach with faculty. Tomorrow: police officers.

Peter Haidu

Clearly, the occupation of university buildings in a student strike infringed on the normal process of education. Any labor strike disrupts normal life. Daily blanket bombings of Vietnam and Cambodia also disrupted normal life: they tore human flesh, burned hair and skin, and sundered communal societies. Secretive university agreements, not approved by the Columbia faculty according to university norms, agreements discovered by SDS, had inserted Columbia University into the government’s war program through participation in the Institute for Defense Analyses....

Obviously, the occupation would end badly: that was a given. How badly was impossible to know. I had little sympathy for SDS. But something else was at stake, a far broader notion, that of the student movement. Outside the South and Harlem, students had inherited the leadership role in the political struggle for human decency and social values. There could be no question of abandoning the movement. It was a question of fidelity to a movement of history in which I recognized myself. It was a matter of identification...

Philosophy Hall, occupied by the Ad Hoc Faculty Group, was in disarray [when I arrived on April 23]. It was packed. People milled about, but with no sense of direction. “Membership” was entirely variable and uncontrolled. Mediators made occasional reports at folding tables at the east end of the room; at the west end, young assistant professors sat in bay windows and on radiators, as well as a group of eight or ten secretaries, patiently waiting, eager to be part of the work. As I walked into the large meeting room, there were perhaps a hundred faculty. Even Mike Riffaterre was there—a great teacher, but no liberal!

... Members of the Ad Hoc Group signed up for the hours and building of their choice. During the occupation, faculty presence at the occupied buildings was assured. How did it all work? Why did individual faculty congregate in Philosophy Hall, sign up for tours of duty in front of occupied buildings to prevent a police cleanup of the occupied buildings, and regularly show up? The faculty understood its students because it identified with them and their humanistic and political values, as the students identified with the populations they undertook to serve and—to the extent possible—represented, as well as the unknown victims of their government’s Vietnam aggression. That potential for identification, which is prior to ideology, has disintegrated....

By Tuesday night, April 30, the bust, certain from the beginning, was finally on... The real action came in the form of plainclothesmen, specialists in crowd control, superb at their job, small athletes in jeans and T-shirts who hunkered down and snuck in between the Blues. One by one, they jumped and grabbed the faculty geese standing on the Fayerweather steps, with absolutely superb execution. I was grabbed by one plainclothes cop and literally tossed one to the next, five in a row, until I found myself breathlessly standing on Amsterdam Avenue on my own two feet, totally unharmed. For people removal, there’s no service like the New York City Police Department, 1968 vintage!

Those students inside Fayerweather Hall were removed from the building by uniformed New York City Blues: some were dragged down a curved marbled staircase by the ankles, their heads bouncing against the marble steps, their skin cracked open, blood dripping out. That contrast, in the bust of faculty and students, is instructive of a policy difference. If my treatment by the police was more or less typical, and most other faculty were treated similarly, someone decided to treat faculty gently and student occupiers harshly as a policy decision. It was not rogue cops going crazy on their own inside Fayerweather... As I stood on Amsterdam Avenue, catching my breath, the nurse came by. Smiling, she returned my glasses. Then suddenly, at my left, an angry shape materialized: “This is all your fault, motherfucker.” So spoke Mark Rudd, a man I hardly knew. He had reason to be upset...

Peter Haidu was born in Paris in 1931, emigrated to New York in 1940, and studied at Stuyvesant and North Hollywood high schools, the University of Chicago, and Columbia. He served in the US Army and taught at Columbia, Yale, and the Universities of Virginia, Illinois, and California.

Robert W. Hanning

April 23 was sunny, and I took to lunch a young man whom the Columbia College Admissions Office had asked me to persuade to accept its offer of a place in the class of 1972. Returning to campus, we found it in an uproar, with the lobby of Hamilton Hall packed with students protesting Columbia’s policies, in particular the construction of a gymnasium in Morningside Park... and preventing egress to Henry Coleman, the College’s acting dean...

[On] the third or fourth night of the Rising, [] as had quickly become the norm, 3 a.m. found me in 301 Philosophy Hall, the adopted “home” of the Ad Hoc Faculty Group whose attempt to mediate between the [student] leadership and the central administration was doomed to fail. As my colleagues’ discussions continued, I was unexpectedly called outside the building to meet three students, two young men and a young woman, who had asked for me... they had this urgent message for me to communicate to my colleagues: they themselves were ready to be arrested when the police came to evict the demonstrators, but the faculty must convince the administration not to let the police attempt to clear Hamilton Hall of its African American occupiers lest Harlem, in an act of righteous vengeance, burn Columbia to the ground, the prospect of which horrified them. As one of the young men made this plea, his voice quivering with chill, fear, and fatigue, the young woman began to cry, softly but uncontrollably. I promised to communicate their concern as requested, and they disappeared into the night...

Although the university administration allowed plainclothes police—their badge numbers obscured—to use brute force to clear the other buildings, the evacuation of Hamilton Hall in fact took place without injury under the supervision of uniformed high police brass. At no point, to my knowledge, was damage to university property threatened by residents of Harlem...

Robert W. Hanning, professor emeritus of English and Comparative Literature, taught at Columbia from 1961 to 2006, primarily as a medievalist, but also on issues of race and racism in American literature.

Neal H. Hurwitz

I was twenty-three years old in 1968, one of the youngest faculty members at Columbia. I was sleeping late on April 23 when my girlfriend told me there was a big demonstration on campus and that it included members of the Students’ Afro-American Society (SAS), which was unusual. We had not seen black students as a group at Columbia demonstrations before, but now, it seemed, black and white student leaders had joined to condemn university policies. I headed over to the sundial, then Hamilton, and stayed on campus until the bust.

One of the most salient features of Columbia ’68 was that the occupation lasted as long as it did because of the presence of the disciplined black students in Hamilton Hall. It could be said that Columbia created the core of the black student group when, at that time, it admitted more blacks than ever into the College. The new leadership of SAS—notably Cicero Wilson—stood for a more active approach, just as did Mark Rudd, who displaced the more moderate leadership of the Columbia chapter of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). The Columbia administration asked Mayor Lindsay to evict the “whites” in Low, Math, Fayerweather, and Avery, but—afraid of a negative response from Harlem—to leave Hamilton alone. “All or nothing” was the response from Lindsay and the New York City Police Department (NYPD). Leaving the blacks in Hamilton but clearing out the others wasn’t going to happen, so all five “liberated zones” had the freedom they needed through the weekend of April 27 and 28. The following Monday night, when the time came for the NYPD to clear the campus of protesting students (and so-called outside agitators), I was asked to be the faculty observer at Hamilton Hall. It was striking and anticlimactic to see the students line up silently in the building’s basement, under the orderly control of the police and in the presence of African American attorneys who had spent days negotiating with the authorities, and exit onto Amsterdam Avenue, where police vans were waiting. No one was injured. The operation was done effectively and efficiently.

For years I have wondered whether the black student leadership ever told the Strike Steering Committee or SDS of their plans for a negotiated, peaceful departure. If not, why? And, if so, why didn’t anyone let the occupiers of Low, Fayerweather, Avery, and Math know that such an arrangement had been made? This might have made the police ejection of hundreds from the four “white” buildings bloodless. It was clear from the start that Mark Rudd and the strike leadership were prepared to allow and even facilitate a violent police response on campus. I respected the decision of students to take a stand, but it was obvious that the Strike Committee was not willing to negotiate. Its leadership did not care that police on campus would be detrimental to all, something that many of us were aware of and that we on the Ad Hoc Faculty Group worked hard to avoid. In the end, the black students of Hamilton—who had won on the issue of the gymnasium in Morningside Park—also decided that violence was not the best option. It is a great shame that President Grayson Kirk, Vice President David Truman, and the Columbia trustees failed to resolve the situation without police. We hoped for rational behavior and creativity on their part...

We knew that off somewhere else was a group of faculty “lions,” men like Lionel Trilling, Fritz Stern, Daniel Bell, Eli Ginzberg, and William Leuchtenberg, an older cohort, men insistent that the university was at great risk and that the protesters must be stopped. Some of them likened the protesters to what Nazi and Communist youth had done to destroy democracies. It was a tense and demanding time, and every moment of that week was an on-site lesson in politics, as informative and educational as anything encountered in the classroom. With neither side willing to negotiate, there was no middle ground to be found, and along with Westin, I realized our task was futile. There was also a sadness, because, as David Truman’s memoir about 1968 shows, he felt betrayed by the AHFG, which positioned itself as a locus of power, as he saw it, against the administration. Most of us liked and respected Truman and expected him to succeed Kirk as president. But that was not to be.

Neal H. Hurwitz led the Friends of Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee at Columbia University 1964–1965, was a teaching assistant in the Graduate School of Arts and Science 1967–1969, and a leader of Students for a Restructured University 1968–1969, which helped created the Columbia University Senate.

Copyright (c) 2018 Columbia University Press. Used by arrangement with the publisher. All rights reserved.