Remembrance of Things Not Yet Past: A Report from “Difficult Histories / Public Spaces: The Challenge of Monuments in NYC and the Nation”

By Arinn Amer

A year after white nationalists descended on Charlottesville, Virginia in a deadly riot they framed as a protest against the planned removal of a bronze rendering of Robert E. Lee from Emancipation Park, monuments loom large in our national consciousness. With new memorials and markers raising awareness of America’ dark history of racial terror and hundreds of Confederate flags and generals retreating from public view even as thousands more remain firmly entrenched, the incredible power of the stories we tell about the past in shared physical space has never been more apparent.

“Difficult Histories/Public Spaces” is an ongoing public programming series conceived as a forum to bring New Yorkers together to grapple with questions about historical representation and memory in our city and beyond. I had the privilege of co-organizing and moderating the first event, a contentious yet illuminating conversation between invited speakers and audience members centered around New York’s long-protested memorial to 19th-century gynecologist J. Marion Sims, whose disputed contributions to medical science were based on experimental surgeries on enslaved women who could not give their consent. The memorial’s centerpiece, a nine-foot-tall bronze statue of Sims, was recently removed from its granite plinth at Fifth Avenue and 103rd Street for transportation to Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery, where Sims is interred.

These are my takeaways from the June 13 panel.

1. Panelists emphasized that a twelve-year campaign for the memorial’s removal was led by local women of color.

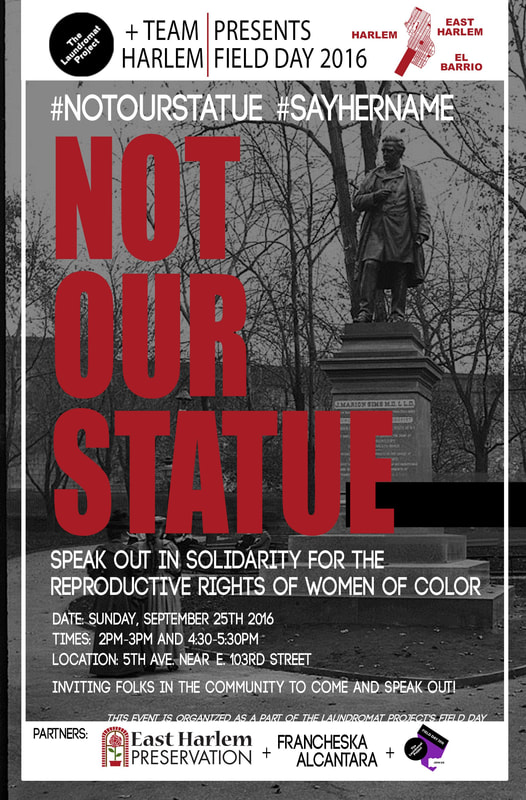

Poster promoting a protest event at the J. Marion Sims statue, 2016.

Marina Ortiz, a community activist and preservationist central to the call to knock Sims off his pedestal, dated East Harlem’s rejection of the monument to Harriet Washington’s 2006 publication of Medical Apartheid, her critically acclaimed account of the American medical establishment’s exploitation of black bodies for unethical experimentation since the colonial era. From there she described an energetic and resourceful campaign: Viola Plummer collected signatures for a petition; Ortiz’s group East Harlem Preservation organized public panels; local artists and writers constructed site-specific installations and staged plays. In 2011 Community Board 11 under the leadership of Diane Collier pressed the Parks Department to take the statue down; more recently vandals graffitied it with red paint and attempted to saw off the head. “None of this is new,” she explained, “we’ve been at this for years.”

Multidisciplinary artist Francheska Alcantara shared footage of the evocative September 2016 action she developed in collaboration with community arts organization Laundromat Project, during which she stood in front of the Sims memorial in a crisp white dress with red paint on her bare feet and wrapped her head in red gauze. She then rehearsed the reparation of sisterhood and community by allowing attendees to help her unravel it as they recited a #SayHerName call and response chant. Alcantara took time to acknowledge and present the work of interlocutors like Sandy Williams, Karyn Olivier, Doreen Garner, and Cynthia Tobar, and artistically-minded protest groups like Decolonize This Place, Monument Removal Brigade, and Black Youth Project 100.

Deirdre Cooper Owens, a historian of slavery and medicine whose research reveals that Sims trained enslaved women whose vaginal fistula he repaired to assist in later experimental surgeries, praised Ortiz’s decades-long activism, and joined Alcantara in citing BYP100’s influential August 2017 action “Fuck White Supremacy!” She credited BYP100 New York chapter co-chair Jewel Cadet with publicizing Sims’ subjects’ coerced contributions to the medical field by christening them “the mothers of modern gynecology,” a pithy reversal of the honorific traditionally ascribed to Sims which had become independently central to Cooper Owens’ scholarship.

These gracious yet insistent attributions fittingly documented and amplified the work of women of color to advocate against a memorial that came to represent the erasure of black women’s voices, labors, and suffering from the historical and medical record. Current plans for the statue’s graveside installation include posted language that mentions Lucy, Anarcha, and Betsy, the three identified enslaved women on whom Sims operated, by name. Perhaps the newly-vacant Fifth Avenue site could benefit from public recognition of the many black and Latina women our speakers cited as responsible for first identifying the oppressive history being naturalized by the monument and working to reverse its harm in their community.

Black Youth Project 100 protesting at the statue, August 2017.

2. Scholars encouraged attention to context when assessing historical figures and their interpretation through works of public art.

Art historian Harriet Senie, who served on the Mayoral Advisory Commission tasked last year with evaluating New York’s public art, monuments, and markers, cautioned that the city’s contested works are extremely complicated. Senie advocated an additive approach to making the public aware of historical context that may not be clear from observing the memorials themselves. She argued that original circumstance can impact meaning, as in Marshal Pétain’s induction into the Canyon of Heroes prior to his collaboration with Nazis during World War II, or sculptor James Earle Fraser’s inflammatory 1940 decision to include an armed black man alongside Theodore Rooselevelt in the American Museum of Natural History statuary now considered inflammatory for its stereotypical depiction of that same black man. “When we think of the artistic conventions at play, it’s not as simple as it sounds,” she said.

While sensitive to intent, Senie also explained that monuments’ meanings can change over time. Though she did not comment on the potentially oppressive symbolism they could take on, she pointed to recontextualizing installations like Tatzu Nishi’s 2012 Discovering Columbus, which rendered the controversial monument a commentary on the extreme privatization encroaching on public space in New York City; and to the early Civil Rights Movement’s transformation of the Lincoln Memorial, which originally honored Lincoln’s deliverance of the Union with no mention of the legal end of slavery, into a strategic protest site symbolizing the unrealized promises of full citizenship and equality.

Tatzu Nishi: Discovering Columbus, 2012.

Senie and Cooper Owens argued that academics should continue partnering with the public to infuse nuance into conversations about the past. In her discussion of the Fraser statue, Senie attempted to convey the difficulty of understanding a figure like Theodore Roosevelt — whom she described as a conservationist, eugenicist, imperialist, and domestic race relations progressive — “in the multifaceted complexity of his time,” remarks which Marina Ortiz took as morally relativistic apologia. But Cooper Owens reiterated that historical figures can encompass multiple identities, arguing that Sims was neither a selfless savior nor a sadistic monster, but a physician, entrepreneur, and white Southerner in many ways typical of the history of American gynecology, a field advanced through access to the vulnerable populations created under slavery.

Cooper Owens addressed the limitations of certain talking points lately in circulation regarding Sims’ experiments. Referencing a growing body of (female-authored) scholarship which shows that American slavery was created and propagated through the mediation of black women’s bodies, she explained that the claim that Sims intentionally harmed his subjects’ reproductive systems ran contrary to the disturbing logic of slavery. “The one thing a slave owner does not want to do is destroy the reproductive capabilities of black women. Literally, the institution rests in their wombs.” She added that heavy loss of life and failure to administer anesthesia were commonplace in surgeries of the 1840s, when the most handy and reliable way to tell if a patient was alive was often pain response, and are less suggestive of misconduct than the birth of a mixed-race child to one of the women Sims leased, operated on, and then trained as a surgical assistant. For Cooper Owens, this complex history demonstrates the fragility of racist antebellum fictions about the superior pain tolerance and inferior intelligence of black women, and provides a rare window into their lived experiences — one which is lost if we fall back on easy binaries of heroes and villains.

3. Activists argued against the need to memorialize unjust history already well understood by the communities it continues to marginalize.

Ortiz dismissed the familiar critique that removing monuments is presentist censorship of the past, instead reframing the issue as one of selective memory that has meant lavishing recognition for important achievements onto white men while withholding the same from women of color. Alluding not only to Sims’ exploitation of enslaved bodies but also to non-Western not-for-profit medical practices pioneered long before his lifetime, Ortiz lamented the asymmetry of the official record offered in the press, textbooks, and state-sponsored sites of memory, promoting communal knowledge and oral history as correctives. “None of this is ever honored, or made into monuments, and I wish it was. If you really want to talk about not erasing history, let’s go back, let’s go there, and let us tell our stories.”

She highlighted the irony of being accused of erasure and historical short sightedness in a campaign she said was in fact about combating both, pointing to East Harlem Preservation’s extensive engagement with the public about the very history that critics have alleged the group is attempting to efface. Indeed, throughout her presentation Ortiz made frequent originalist appeals, as when she dismissed Harriet Senie’s framing of the Columbus Circle monument as an artifact of 1890s Italian American activism against anti-immigrant violence with the claim that Columbus was not meaningfully Italian because he lived prior to the existence of modern nation states, or when she pointed out that the New York City Parks Department, whose Arts & Antiquities Director opposed the relocation of the Sims monument as revisionism, had set the precedent for removing art for content by foisting the statue off on East Harlem during an overhaul of Bryant Park in 1934. (She did not note that East Harlem was then a predominantly Italian American neighborhood.)

Both Ortiz and Alcantara submitted that a true reckoning with the past must include acknowledgement of its continuities into the present. Ortiz shared that she was motivated to advocate for the memorial’s removal in part because of the parallels she saw between Sims’ experimentation and the targeting of Puerto Rican women as unwilling objects of sterilization and birth control experimentation as recently as the 1960s. If she and Alcanata invoked the most chronologically remote history, harkening back to the fifteenth-century beginnings of settler colonialism and native dispossession in the Americas, they were also most insistent that this history remains immediate and unresolved. Each opened her remarks with reference to our ongoing occupation of indigenous lands, Ortiz in an improvised condemnation of Theodore Roosevelt’s conservationism as the mere stockpiling of stolen forests, and Alcantara with a mindful declaration of her intent “to assume a position of respect for the struggle of First Nations to truly achieve the decolonization of their territory.” Such statements have become an important fixture of intersectional activism, but also represent a distinctive conception of history as not-yet-past which quickly renders preposterous the fear of forgetting what’s memorialized all around us in systemic injustices and, as Ortiz added, intergenerational trauma.

Far from indifferently reporting the past, Alcantara suggested, the Sims monument and others like it persist in actively shaping our present. With her street performances that rehearse cultural resilience in communities affected disproportionately by poverty, housing inequality, and police brutality, Alcantara aims to provide alternatives to the oppressive visual narratives that champion white supremacy and capitalism in public space. The artist explained that public spaces often masquerade as neutral, but in fact are social constructions designed to uphold the intertwining power dynamics of colonialism, imperialism, capitalism, and racism that have “excluded, undermined, and posed a threat to communities of color.” Like the Confederate monuments she clarified were erected at times when white Southerners wished to use public visual narratives to exert white supremacy, the memorial to Sims was never a simple recounting of the past. Though it may have been invisible to many New Yorkers until recently, Ortiz agreed, the monument was not without corrosive influence.

4. Increasing the demographic diversity represented in New York’s public memorials was hailed as the way forward, but would address only some of the issues that emerged from the discussion.

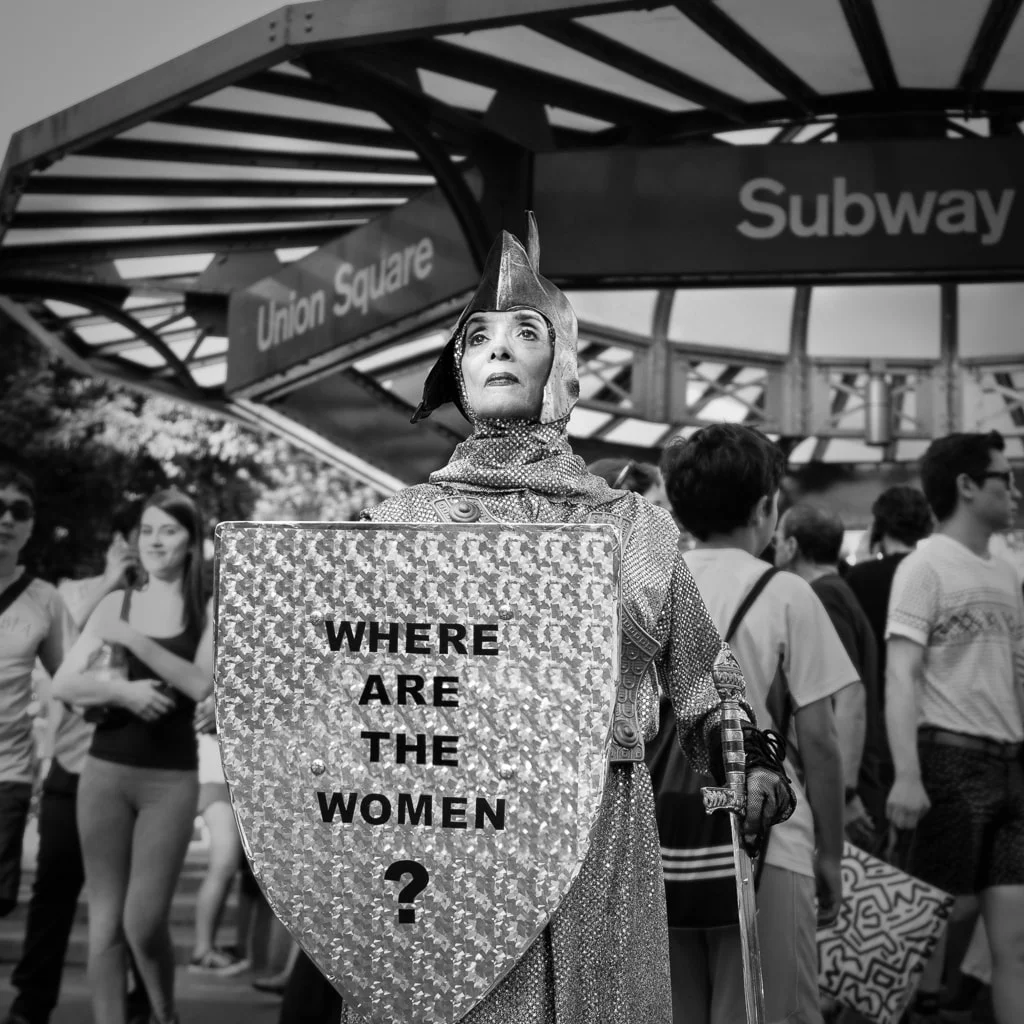

Ortiz was adamant that the 103rd Street site should be converted into a memorial to a woman, ideally a local woman of color portrayed by a local artist. She suggested several candidates who have contributed to medical science, among them Helen Rodríguez Trías and Rebecca Lee Crumpler. “That’s the kind of people we want to see, people who look like us and have our history.” Citing the performance work of East Harlem artist LuLu LoLo, who has been taking to the streets in a Joan of Arc costume to survey New Yorkers about the women they would like to see depicted in public memorials in a campaign entitled “Where Are the Women,” Ortiz said it was high time for gender diversity in city memorials.

LuLu LoLo as Joan of Arc of 14th Street— Asks “Where are the Women?” A Call for Monuments of Women in New York City, 2015. Photo by Keka Marzagao.

In a significant consensus between two presenters who had advocated opposing positions throughout much of the program, Senie concurred, and was happy to report that there are studies in progress by the Department of Cultural Affairs and the Ford Foundation to identify populations under-represented in public art. When it came to the form that new memorials to women should take, Ortiz and Senie once again found themselves in agreement. Ortiz rejected an audience suggestion that interactive tours like the Jane’s Walks she has led can replace the function of statutory, advocating instead for the kind of silent instruction traditional monuments can impart during a stroll through Central Park. Senie argued that ephemeral memorialization has its place, but that honoring women in the classic figurative mode once reserved for the likes of Sims is crucial too. “There’s something about the relative permanence of a statue that conveys respect in the way that it has traditionally,” she explained, “and we want to see other people represented in those ways.”

Still, a slew of questions remain. How will New Yorkers craving more diverse representation respond to Central Park’s first slated statue of real women, a memorial to the women’s suffrage movement which will portray Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, two elite white women who were vocal feminist activists and prescient critics of biological determinism, who have also been criticized for their failures to fight for the rights of working and immigrant women and people of color? How can permanent installations like this one reflect interpretive changes as historians like Cooper Owens endeavour to read the historical record for missing voices? How can they resist the embedded visual grammars of white supremacy, capitalism, and nationalism which Alcantara critiques in her work?

Have we entered a post-pedestal era? Who should have the authority to determine the histories memorialized in public space? And in a New York as over-priced as it is over-policed, where is this public space we speak of?

Arinn Amer is a doctoral candidate at the CUNY Graduate Center and teaches early American history at Hunter College. Her research probes the connections between colonial culture and tar and feather violence. Together with Madeline DeDe-Panken she co-chairs the CUNY Public History Collective.

“Difficult Histories/Public Spaces” is co-sponsored by the American Social History Project and Center for Media and Learning, the CUNY Public History Collective, and the Gotham Center for New York City History, and supported with funds from Humanities New York and the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Join us at the CUNY Graduate Center’s Segal Theater at 6:00 p.m. on October 9, 2018 and February 6, 2019 for parts two and three of “Difficult Histories/Public Spaces,” where we will confront the institutional process of monument creation in New York City and the future of alternative approaches to memorialization.