Rivers, Filth and Heat: Riverbaths and the Fight over Public Bathing

By Naomi Adiv

In the summer of 1870, New York City got its first municipal bath: swimming pools sunk into the rivers, through which river water flowed. An 1871 New York Times article describes them: “baths are of the usual house-like model, and have a swimming area of eighty-five feet in length by sixty-five feet in width. They are… provided with sixty-eight dressing-rooms, have offices and rooms in an additional story, and are well lighted with gas for night bathing.” In the year after they were built, the Department of Public Works reported that they were regularly used to their capacity, particularly on hot summer days. At their height, there were twenty-two such baths around the waters of New York City.

From the start, the municipal baths had a contested symbolism. On one hand, they allowed for much safer river bathing in the hot months, especially as compared to swimming in the currents of the rivers and harbor. A study taken at the time shows that, in 1868, drownings averaged about one per day. Additionally, in the minds of the political and philanthropic leaders who concerned themselves with the well-being of the poor, the riverbaths were meant to be places for cleansing; cooling was also a priority in an era before air conditioning. Additionally, some of the first state-sponsored swimming lessons in New York went on in the floating baths, funded by the Board of Education. And, if not on the official agenda, photos and engravings show us that play and splashing were also prominent among those who frequented the riverbaths.

Municipal Floating Bath #2, Brooklyn. (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1904)

Did New York’s poorest citizens use the river baths? Did they like them? Many accounts from the time indicate indicate that the riverbaths were very well used. In 1870, the first year they were open, each of the two original floating baths accommodated about 4,500 bathers per day, and commentators in the newspapers called for more. However, some secondary accounts differ, noting that the baths had a reputation as “floating sewers.” Further, the policing of the riverbank outside of the baths compelled people to use them if they wanted to bathe in the river without threat of police harassment.

The pollution got worse as the years went on: the rivers carried sewage, industrial wasted, and blood from slaughterhouses. Yet the riverbaths remained popular, as did open river swimming. When the indoor bathhouses that had been promised for so long finally opened in 1901, the Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor — a philanthropic organization that was instrumental in building the bathhouses — called for the Health Department to shut down the riverbaths. There was cause for concern. In their own words,

an epidemic of pinkeye in Brooklyn last year was traced to one of the baths there near a trunk sewer. Besides that, the river bath can only be open during the summer. It is the duty of the city to assume the municipal activity of providing for the cleanliness of its tenement dwellers. This is not merely to cultivate habits of cleanliness, although a bath is the beginning of self-respect, but as a preventive of disease.

Yet the Health Department understood how complex the issue was. A few years later, in 1903, Health Commissioner Lederle called to keep the baths open, and to site them “in the best places which can be found and where the water is as little contaminated as possible.”

Health Commissioner Lederle

When the Department of Public Works and the Health Department moved to close the river baths for good, on sanitary grounds, the decision was met with suspicion by poor people that the City wanted to close the river baths in order to force patronage at the indoor baths, which Health Commissioner Lederle denied. When the decision was finally made, Lederle made clear that the river baths had been kept open as long as they had because it would be unfair “to deprive the poor of their only means of open-air bathing without providing some sort of a substitute.” In public hearings, discussion also included the question of whether more people would get sick from the river water or from summer heat in the city.

The solution, in 1914, was to make the floating baths watertight, and to fill them with purified, filtered water. Even with the baths sealed and filled with Croton water, an argument remained over whether the money needed to sustain the river baths, now much more expensive, should be appropriated, and from where. Manhattan Borough President Marks, with the support of Mayor McAneny, insisted on municipal provision of the river baths, openly fighting with the City Controller’s office: “To swim in the open air and sunshine is what the children want. If they jump into the river they are arrested, and what are they to do? The floating baths have always been very popular, and they are in locations where no proper interior baths are accessible.”

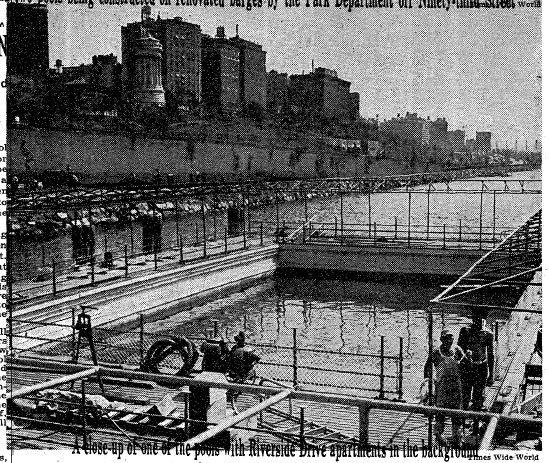

Although their popularity had declined somewhat as beach bathing became more accessible, seven floating pools still operated in 1932, as public health experts and city officials still struggled to keep people out of the rivers, due to the pollution and regular drownings. There was also the simple distaste that many city officials (including Parks administrators and Police) had for the nudity they had been trying to stamp out for more than sixty years. The Department of Health sponsored a program in 1937-38 in order to teach children the dangers of East River swimming. In the same period, the Department of Parks made one last attempt to save the floating baths, by attaching them to barges in the East River, and the Hudson River at 96th Street; by 1942, they were defunded and abandoned.

Barge pool, New York Times, August 3, 1938

Although the river baths are often considered a quirky footnote to the bigger program of parks and pools in New York City, they survived in some form for almost seventy-five years, and seem to have been quite popular for at least forty-five years. The story of their persistence can help us to understand how cities imagine and build public spaces over time: the shifts between public bathing structures — river baths and indoor baths, and eventually modern swimming pools — always ran up against one another, sometimes disruptively, based in social ideas and government structures. Meanwhile, people (mostly children) continued to swim in the rivers around New York through the 1940s.

The story of the river baths nudges us to question who the public is in public space, and who gets to make the decisions about how public spaces are formed and funded. Provision of public space is a perennial challenge to the democratic ideals of the city, as clashing values and disputes over resources get played out in the management and use of everyday places. These geographies of swimming and splashing and laughter and beating the heat, small though they may seem, have intervened in the life and the lives of the city for almost 150 years.

River baths, 51st Street West, Manhattan, NYPL 422699

Naomi Adiv is Assistant Professor of Urban Studies and Planning at Portland State University. She holds a PhD from The Graduate Center, CUNY.