Roar, Lion, Roar: Columbia Football History

By Joanna Rios and Jocelyn Wilk

"Roar, Lion, Roar: A Celebration of Columbia Football" exhibition poster.

This fall, the staff of the Columbia University Archives curated an exhibition at the Rare Book & Manuscript Library's Chang Octagon entitled "Roar, Lion, Roar: A Celebration of Columbia Football" (August 26-December 20, 2019). It's been a labor of love for us and we are thrilled to share the stories, artwork, photographs, and documents that tell the history of one of the oldest college football programs in the country. Our exhibit consists of six wall cases and three display cubes. It is not the biggest of spaces, but in it, we are able to showcase the places, the people, and the high and low points of this distinguished athletic program. But not everything can make it into the exhibit.

Exhibitions are fantastic outreach opportunities. They allow you to show off treasures from your collections and are an exciting opportunity to dive deeply into your collections. As anyone who has curated an exhibition can attest, the research process usually reveals far more information, stories, and items for possible display than you actually have space to accommodate. This one is no exception. We now know far more about Columbia's football program than we ever expected – and are happy to share some of the more obscure, yet still fascinating, New York City-themed vignettes discovered as we researched this topic. The stories that follow did not necessarily make it into the exhibition currently on display, but that doesn't mean they are not interesting!

Early Football

Cover of the football program for Rutgers vs. Columbia, September 25, 1948. Present-day (1948): Columbia and Rutgers football players stand in front of a portrait of their 1870 counterparts. Columbia played its first intercollegiate football game against Rutgers in 1870. Department of Intercollegiate Athletics Records, Columbia University Archives.

Columbia played its first intercollegiate football game on November 12, 1870. A team of twenty players journeyed to New Brunswick, New Jersey to play against Rutgers in only the fourth game in the history of the sport. Rutgers and Princeton had played each other twice in 1869 and a third game just two days before Columbia's first game. Stuyvesant Fish, Columbia College Class of 1871, was elected captain of the twenty-player team. Back then, there were only 125 students enrolled at the College located on 49th Street and Madison Avenue. Columbia lost to Rutgers by a score of 6-3 on that Saturday.

If the score of 6-3 seems odd, that's because the game back then was very different from the game played nowadays. The points reflect the number of games each team won or who scored first to end the game. The match started at 11:50 am and the first game lasted 45 minutes. They played another eight games until Rutgers was declared the winner at six games to Columbia's three. The leather ball was not yet in use. Players used a black rubber ball (a sphere, not an oval) that could be batted with a fist as well as kicked past the goalposts. There was no training, no practices, and no coaches. The Rutgers hosts did hold a dinner, and later that day, the teams also played two innings of baseball, which Columbia won 7-5.

Places to Play

Columbia vs. University of Pennsylvania football game at the Polo Grounds with the subway in the background (1920s). Historical Photograph Collection, Box 145, folder 1, Columbia University Archives.

Did you know Columbia University has had three homes since its founding in 1754? It was first located downtown at Park Place, then moved to 49th Street and Madison Avenue, and then finally landed in Morningside Heights. In a similar fashion, Columbia Football has had several home fields since they started playing the game in 1870…and one "almost" home.

Before the school moved uptown to its current location, Columbia played their home games at the “Columbia Oval” in Williamsbridge, Manhattan Field, and even the Polo Grounds. The current lawns in the middle of campus, now known as South Lawn, once formed a contiguous strip of grass where football games, practices and other sporting events were held. South Field, as it was called, opened as a practice field when the University moved to Morningside Heights in 1897 and was the home field for football games from 1915 to 1922. In 1923, football found a new home at the tip of Upper Manhattan at what is known as Baker Field. This land was given to Columbia by financier and banker George F. Baker, who had purchased it for $700,000 on December 31, 1921. A stadium for Columbia football games has occupied this site ever since.

Before Baker Field, there was a short-lived plan by Columbia's President Nicholas Murray Butler to use a landfill in the Hudson River to create an athletic field and a stadium closer to campus. Per a Spectator article dated February 27, 1953, by the beginning of the 20th century, the University Trustees felt that South Field was too crowded to provide adequate student recreational facilities. In his 1906 report, Butler announced a plan to build a $1,000,000 athletic field by filling in the Hudson River between 116th and 120th Streets. The new stadium was to be a steel structure with two decks of stands perpendicular to the shore. Later that year the University got the necessary legislative consent for the new project.

Although the project rapidly gained student and alumni support in those early days, the plan lay essentially dormant until 1920, when it was vigorously revived with the students demanding immediate action. In 1921, Butler decided to appoint a committee to determine if it was practical. The committee reported three major findings: first, the space they would be able to fill in would be inadequate to build a stadium large enough to hold major athletic events; second, even under the most generous interpretation of the 1906 legislative act, it was discovered that filling in the region would obstruct navigation on the Hudson; and third, the present (1921) prices would make the cost of the stadium $3,000,000 instead of the 1906 estimate of $1,000,000. The project was quickly dropped and the trustees started shopping around for another field.

Play Ball! Columbia Football and the New York Yankees

There are some interesting intersections between Columbia Football and the New York Yankees. In our exhibition, we highlight former Columbia Lion Lou Gehrig, Columbia College Class of 1925. Gehrig played freshman football in the fall of 1921 and joined the varsity squad in the fall of 1922. After playing baseball in the spring of 1923, Gehrig signed with the New York Yankees in the summer of that year. But that is not the only Columbia Football-New York Yankees connection.

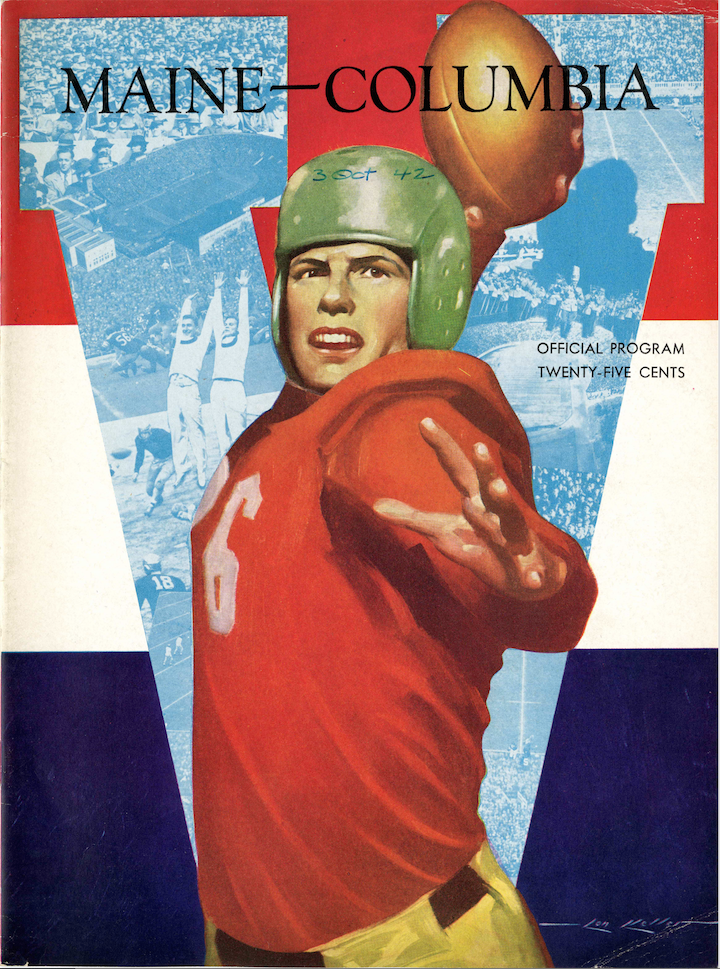

During our research for the exhibition, we noticed that in the 1940s, the cover artwork on the football programs seemed not-Columbia specific. For example, the football player on this 1942 cover is wearing a red and green uniform (not the Columbia Blue) and the photographs in the "V" shape include a stadium (not Baker Field) and marching band. In fact, in 1943, we found the same cover image for a Columbia home game (against Princeton) as for a Cornell home game (against Columbia): both institutions licensed and featured the same artwork just a few weeks apart.

Cover of the football program for Maine vs. Columbia, October 3, 1942. Artwork by Lon Keller. Historical Subject Files, Box 93, folder 2, Columbia University Archives.

The work was done by sports artist (and New York Sports Museum & Hall of Famer) Henry Alonzo Keller, or as he signed his name, Lon Keller. Keller’s work was featured in countless professional, college, and high school program covers for football, basketball, and baseball. But his best-known work is the New York Yankees top-hat-on-the-bat logo, which first appeared in 1926. Keller’s work graced the covers of Columbia football programs and New York Yankees programs during the 1940s and 1950s. You can find Columbia football programs in the University Archives’ Historical Subject Files and you can also view a gallery of Lon Keller’s work online at http://www.lonkeller.com.

Rose Bowl

Mayor Fiorello La Guardia welcomes Coach Lou Little at Penn Station after Columbia's victory over Stanford at the 1934 Rose Bowl game. Lou Little Papers, Box 3, folder 1934, Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

One of the highlights in the exhibition and in the history of the football team is Columbia's 7-0 victory over Stanford at the 1934 Rose Bowl. Back then, the Rose Bowl, inaugurated in 1916 and held annually on New Years' Day in Pasadena, California, was the only college bowl game. The Orange Bowl and the Sugar Bowl wouldn't begin until 1935, and the Cotton Bowl, in 1937. Shortly after the Lions closed the 1933 season with a 16-0 shutout of Syracuse and an overall 8-1 record, the Rose Bowl extended an invitation to Columbia. Many sportswriters and fans gave Columbia little chance of victory. Even the student newspaper, the Spectator, didn't think Columbia should attend the game. However, in one of the biggest upsets in college football history, Columbia defeated Stanford 7-0.

With the team on its way home to New York, there were plans for multiple celebrations. Columbia University President Nicholas Murray Butler announced that the welcome event had to be held on campus. Butler even requested via telegram that the newly sworn-in Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia abandon his plans for an event at Penn Station. LaGuardia was allowed to meet the team at the train station but then, with a police escort, the team was to be transported directly to Morningside Heights for an official campus celebration.

Regardless of Butler's request, on Sunday evening, January 7, 1934, well over 5,000 New Yorkers stormed Penn Station to wait for the "Columbia Special." Some 200 NYPD officers were on duty to manage the crowd (and to cheer on the returning champions). Another 100 patrolmen were assigned to the campus. While the crowd waited, "[t]he train-calling system of the big station, with its radio amplifiers, had been turned over for the occasion to Columbia and it blared forth the football songs of the university. Hawkers peddled Columbia pennants and medallions through the crowd, which grew until it packed nearly half of the great floor space." It was, according to the New York Times, "one of the biggest receptions New York has accorded a returning athletic team." (January 8, 1934, page 14).

The Streak

Columbia Spectator front page from October 10, 1988 reporting on the end of Columbia's 44-game losing streak. Historical Subject Files, Box 90, folder 4, Columbia University Archives.

On October 8, 1988, Columbia defeated Princeton 16-13 in front of 5,420 cold but happy Lions fans attending homecoming on a gray and windy day. The win broke Columbia’s 44-game losing streak from 1983 to 1988. It also marked the team’s first-ever victory at Lawrence A. Wien Stadium, which had officially opened in 1984. While Columbia’s 44-game losing streak was an NCAA record at the time, the current record belongs to Prairie View A&M, which lost 80 consecutive games from 1989 to 1998.

In preparing the exhibition, we learned about some of the factors that contributed to the Streak. First, the travel distance: Columbia's main campus on Morningside Heights is 5 miles away from the practice field. This means more travel time (and less practice time) and limited access to the facilities. Second, defeat leads to a losing syndrome. Multiple losses mean that players do not have a chance to develop or grow, they become defeatists and some even drop out. Non-competitiveness, or constant defeat, also hampers recruiting efforts. Losing leads to a lack of belief and enthusiasm in the players and a lack of respect, support, and encouragement from students, faculty and alumni. A third factor, one that surprised us, was the very collegiate issue of room and board. It wasn't until 1988, with the opening of Schapiro Hall, that Columbia was finally able to guarantee student housing for all Columbia College and Engineering students for four years. Since not all students lived on campus, this meant that dining options were similarly limited. The Columbia meal plans provided only seven "all you can eat" meals a week and limited "dining dollars" to eat other meals in satellite facilities. The availability of food was inadequate both in quantity and quality for an active student-athlete. While the Streak is now infamous, it also shows the effects of two basic issues of living in New York City: commuting and housing. That is partly why in the display cases, we focus on the celebration from that one victory: the relief, the pure joy and the coming together of the campus.

The exhibition is open to the public and on display through December 20, 2019, during regular open hours (Monday-Friday 9:00 am to 4:45 pm). The Rare Book & Manuscript Library (RBML) is located on the 6th floor of Butler Library, on the south end of Columbia’s Morningside Heights campus. You can also visit the Columbia University Archives on Facebook and the RBML News blog for more stories, photographs, and artwork related to the history of Columbia Football.

Joanna Rios is the Records Manager at Columbia University’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library (RBML).

Jocelyn Wilk is University Archivist at Columbia University’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library (RBML).