Rufus Gilbert's Elevated Pneumatic Tubes

By Sam Lubell and Greg Goldin

This is the first in a series of posts drawn from the authors' recent work Never Built New York, published courtesy of Metropolis Books.

Rufus Henry Gilbert was among the most influential, and tragic, inventors to promote a mid-nineteenth-century transit scheme. Born in 1832 in Guilford, New York, Gilbert possessed an itinerant and brilliant mind. As a young man, he taught himself classical literature, mechanics, and mathematics; he apprenticed at a manufacturing firm but switched to studying medicine at the College of Physicians and Surgeons, becoming a distinguished surgeon and doctor. At the outbreak of the Civil War, he signed up as a Union surgeon and was decorated for performing the first operation ever done under fire. By war’s end, he had risen to become medical director and superintendent of all U.S. Army hospitals, chiefly training other doctors––who became known as sawbones––in the terrible art of amputation. This was hardly the road to rapid transit.

Chronic stomach ailments, which he had contracted during the war, forced Gilbert to resign his commission and abandon his medical practice. Prior to the war, grieving over the loss of his wife, he had sailed to Europe, where abysmal tenements convinced him that overcrowded slums were the chief cause of disease and early death among the poor. Gilbert’s answer to the cholera, typhus, and diphtheria rampaging among the downtrodden classes was, elliptically, rapid transit. He reasoned that fast and cheap public conveyances would allow the poor to flee their teeming, disease-infested neighborhoods, and live in the hinterlands, where they could enjoy clean air and water, and plentiful sunshine. The pathways to good health were the tracks to suburbia.

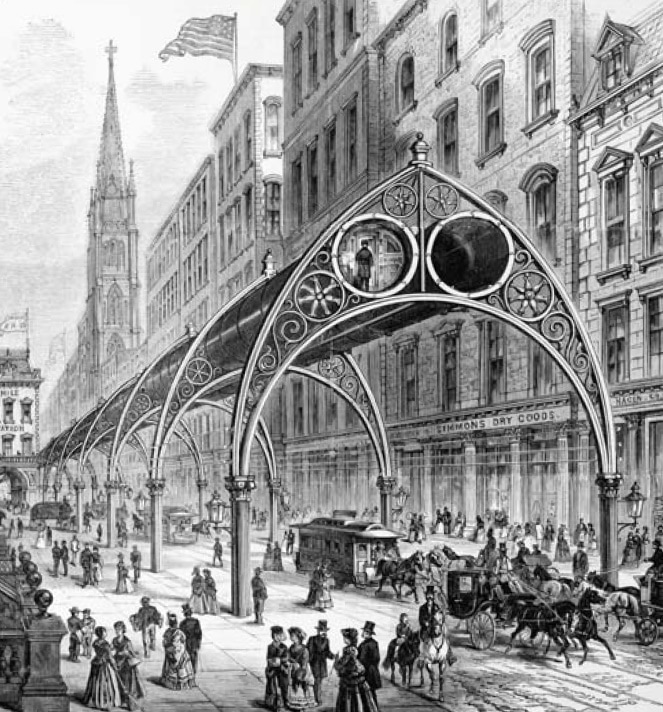

After a stint working as an assistant superintendent for the New Jersey Central railroad, Gilbert at last devoted himself to perfecting rapid transit in New York City. Several iterations on, he came up with his Elevated Railway, for which he was granted a patent in 1870. Gilbert’s design was a hybrid––a combination of Alfred Beach’s air-powered underground and Charles T. Harvey’s cable-powered elevated––which had begun a brief experimental run on Greenwich Street in July 1868. Passengers would waft around town propelled by compressed air, moving through a double row of what Gilbert called “atmospheric tubes.” The elevated tubes, which he envisioned as eight or nine feet in diameter, were suspended from 24-foot-high, wrought-iron Gothic arches, held aloft on slender, fluted, Corinthian columns.

The arches, which were reinforced by trusses elaborately adorned with French curves and spoked rosettes, were a huge hit. The New York Times predicted the elevated would become “the pride and boast of the people living along the line” and lauded its “lightness and beauty of architectural design.”

Gilbert put his stations about one mile apart and provided them with pneumatic elevators, “thus obviating the necessity of going up and down stairs for transit,” said Scientific American. He also planned a telegraph triggered by the passing cars, which would automatically signal arrivals and departures from all points along the line.

In 1872, the state legislature gave Gilbert a charter to build his elevated pneumatic railway. He was allowed three years to span nearly the length of Manhattan, from West Broadway and Reade Street in present-day Tribeca, along Sixth to the Harlem River.

The later-model passenger cars

Then Wall Street collapsed in the Panic of 1873. No one would invest in Gilbert’s fanciful and untested scheme.

Gilbert was not one to give up. He obtained at least two other patents for his “improved elevated railway,” which by 1874 had morphed from the exotic pneumatic into a more conventional steam-powered train––still running on an elevated track, now held aloft on a less-graceful Gothic arch adorned in trefoils.

The great virtue of Gilbert’s plan, according to his civil engineer Richard P. Morgan, Jr., was prefabrication. “As all the parts will be prepared and fitted to each other before they are brought to their places, the structure can be quickly put up, and during the process of erection will occupy no more of the street than is now used by the erection of new buildings.”

In 1875, the state legislature freed the city’s mayor to appoint a Board of Rapid Transit Commissioners, which, in turn, authorized Gilbert to build his line on Second and Sixth avenues. Now he found backers, and on April 19, 1876, construction began at the corner of Sixth Avenue and 42nd Street.

Two years later, on June 5, 1878, the Sixth Avenue El opened, and 30,000 riders overwhelmed the steam cars. Ten cents bought a ride from Rector Street to Central Park, via Church, West Broadway, and Sixth Avenue. The following day, Gilbert was stripped of his seat as a company director and, later, forced out altogether. His former partners, who were tied to “Boss” Tweed, swindled him out of his holdings and erased him from the company name, which became the Metropolitan Elevated Company.

The shady stock swap left the inventor impoverished and broken. He spent the last years of his life pursuing his victimizers in court. Gilbert was last seen on the streets of New York, hobbled, leaning on a pair of sticks as he walked to the elevated station at 72nd Street and Ninth Avenue. He died of his debilitating stomach ailments on July 10, 1885, just 53 years old.

Sam Lubell is a Staff Writer at Wired and a Contributing Editor at the Architect’s Newspaper. He has written seven books about architecture, published widely, and curated Never Built Los Angeles and Shelter: Rethinking How We Live in Los Angeles at the A+D Architecture and Design Museum. Greg Goldin was the architecture critic at Los Angeles Magazine from 1999 to 2011, and co-curator, and co-author, of Never Built Los Angeles. His writing has appeared in The Los Angeles Times, Architectural Record, The Architect’s Newspaper, and Zocalo, among many others.