The Daniel Dromm Collection at the La Guardia and Wagner Archives and the Queens LGBTQ Rights Movement

By Stephen Petrus

Queens Pride Parade co-founders Daniel Dromm and Maritza Martinez at Travers Park in Jackson Heights at "Coming Out against Violence Day," 1996. Courtesy Daniel Dromm Photograph Collection, LaGuardia and Wagner Archives, LAGCC, CUNY

The Collection of Queens City Councilman Daniel Dromm, recently accessioned at the La Guardia and Wagner Archives, will benefit scholars, activists, curators, and policymakers researching LGBTQ studies and recent New York City history in general. Dromm, a Queens public school teacher from 1984 to 2009, was a founder of the Queens Lesbian and Gay Pride Committee and an organizer of the Queens Pride Parade and Festival, inaugurated in Jackson Heights in 1993. Elected to New York City Council in 2009, he represents Jackson Heights and Elmhurst in Queens and is one of two openly gay City Council members from the borough.

The Dromm Collection consists of 24 boxes of documents, 30 multimedia videos, 160 artifacts, and some 3,000 photographs. The bulk ranges from 1990 to the early 2010s. It’s particularly strong on the origins and development of the Queens Pride Parade, containing photographs, correspondence, flyers, pamphlets, permits, registration material, and meeting notes. Artifacts include pins, Frisbees, clothing patches, and T-shirts.

The Dromm Collection will expand the focus of LGBTQ studies beyond Manhattan to Queens. Queens LGBTQ history, in fact, is noteworthy prior to Dromm’s activism. Though there are no known records of LGBTQ groups in the borough before the 1970s, Queens activists likely were involved in the pre-Stonewall organizations Daughters of Bilitis and the Mattachine Society. In the 1970s, chapters of national organizations formed in Queens, including the Gay Activists Alliance in Jamaica and the Gay Human Rights League in Flushing. The 1980s witnessed the establishment of Dignity of Queens, Gay Friends & Neighbors of Queens, and the Lesbian and Gay Political Action Committee of Queens. These groups supported the Gay Rights Bill, passed by New York City Council in 1986 to bar discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation in housing, employment, and public accommodations.

But Queens LGBTQ history is not simply a linear narrative of progress. It’s a tangled story of starts, stops, gaps, and starts again. Recall that in the 1970s the borough’s most famous resident was the fictional Archie Bunker, a reactionary conservative, blue-collar worker, and family man, often described as a “lovable bigot.” During the contentious Democratic mayoral primary of 1977 between Mario Cuomo and Ed Koch, signs appeared in Queens urging residents to “Vote for Cuomo, not the Homo.” In a borough made up of culturally conservative neighborhoods, LGBTQ activists faced backlash, especially during the AIDS crisis of the 1980s. For example, the establishment of the AIDS Center of Queens County (ACQC) in Richmond Hill in 1986 by Douglas A. Feldman generated controversy, as the disease at the time was largely associated with gay men, prostitutes, and injecting drug users. Following a march against ACQC led by Assembly Member Anthony Seminerio, the center moved to Forest Hills. And on July 2, 1990, in an incident that traumatized the Queens LGBTQ community, Julio Rivera, a gay bartender, was murdered in a Jackson Heights schoolyard by three young men out “hunting homos” after a night of heavy drinking. The killing led to demands for justice and sparked a wave of activism.

Against this backdrop of hope and despair, Sunnyside fourth-grade public school teacher Daniel Dromm set out to institute a Queens Pride Parade. Dromm viewed a parade as a forum for people to come out, arguing that the best way to do it was in a public space, with crowds cheering, music blaring, and motorcycles rumbling. He also wanted to draw attention to the relatively unknown Queens LGBTQ population. Until the early 1990s, most New Yorkers associated the city’s gay and lesbian community with Greenwich Village.

The catalyst for Dromm was the rejection of the citywide Children of the Rainbow Curriculum in Queens Community School District 24 in 1992. Amid heated debates about multicultural educational policy in New York, the curriculum promoted racial and ethnic harmony and urged tolerance for gays and lesbians. Advocates argued it was imperative for minority students to see themselves represented in the classroom. Critics cited references to families headed by same-sex couples as well as the three recommended books Heather Has Two Mommies, Daddy’s Roommate, and Gloria Goes to Gay Pride. Dromm came out in public as a gay man and became a champion of the curriculum. He also began to plan a parade with fellow activist Maritza Martinez. On November 4, 1992, he held the first meeting for the event in his apartment. Four people attended.

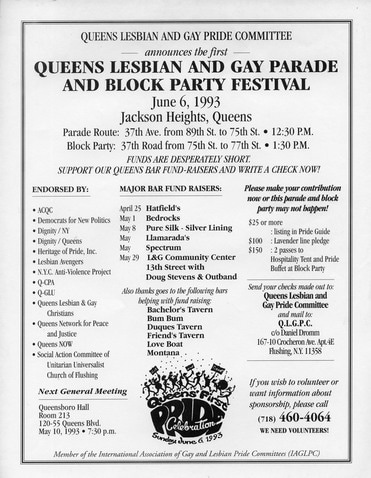

The inaugural Queens Lesbian and Gay Parade and Block Party Festival on June 6, 1993 in Jackson Heights marked a watershed in LGBTQ history. Some 1,000 marchers participated, and thousands of spectators attended. More than a dozen LGBT organizations sponsored the event. City Councilman Tom Duane and Assemblywoman Deborah Glick, both of Manhattan, served as grand marshals, along with activist Jeanne Manford, founder of PFLAG (Parents, Families and Friends of Lesbians and Gays.) The locale was of particular significance. “Gays and lesbians should be able to feel comfortable in all parts of the city, not just in Manhattan,” remarked Queens resident Brendan Fay, a member of the Irish Lesbian and Gay Organization. Q-GLU member Guillermo Vasquez observed, “It is important to send a message to politicians that there are large numbers of us in Queens.” He added, “Queens is coming out of the closet.”

The Dromm Collection illuminates grassroots activism. Behind the scenes, activists raised funds, mailed out newsletters, and lobbied politicians. The work was often tedious but gives insight into the nature of social activism, typically associated with climactic protest, dramatic clashes, and vivid images. What often gets overlooked, but not in this collection, is the work that occurs out of the spotlight, including the organizing, petitioning, and volunteering. One photograph depicts a 1994 “mailing party,” when volunteers sent out some 4,000 newsletters.

The initial Queens Pride Parade was in essence a community event, financed largely by gay bars on Roosevelt Avenue in Jackson Heights and sponsored by Queens and Manhattan LGBTQ organizations. Gritty in appearance, the parade reflected a do-it-yourself ethic. To collect money Dromm and Martinez canvassed area bars with coffee cans. They started to appeal for donations at around 11:00pm, after patrons had a few drinks. On the first night, they collected $54. In subsequent years, parade organizers obtained the support of major corporations, such as Bell Atlantic and Citibank.

The South Asian Lesbian and Gay Association (SALGA) is one of many ethnic groups to participate in the annual Queens Pride Parade in June. Their involvement reflects the diversity of the Queens LGBTQ community. In this particular parade, in 2001, SALGA drew attention to the number of HIV/AIDS cases in India and Nepal, illustrating the global effect of the disease.

Courtesy Daniel Dromm Photograph Collection, LaGuardia and Wagner Archives, LAGCC, CUNY

Queens Pride increased in size and visibility due to the participation of ethnic organizations in the annual June parade. The South Asian Lesbian and Gay Association (SALGA), the Colombian Gay and Lesbian Association (COLEGA), Las Buenas Amigas, and other groups marched, revealing the multiracial, multiethnic nature of the LGBTQ community. “Queens Pride changed the face of the movement,” Dromm observed. Photographs in the Dromm Collection illustrate the diversity.

Queens Pride was seminal. It had a rippling effect in the city, helping to start pride parades in Brooklyn, the Bronx, and Staten Island. It enriches our understanding of the LGBTQ movement. The Daniel Dromm Collection at La Guardia and Wagner Archives will be invaluable to researchers of a social justice movement that has changed American politics and culture in recent decades.

Stephen Petrus, a historian at La Guardia and Wagner Archives, is co-author of Folk City: New York and the American Folk Music Revival (Oxford University Press, 2015). His next book will be a political and cultural history of Greenwich Village in the 1950s and 60s. He also helped to organize the exhibition The Lavender Line: Coming Out in Queens at the Queens Museum to mark the 25th anniversary of the Queens Pride Parade.

For more information on The Lavender Line, on view from June 9 to July 30, 2017, click here.