The Defiant: An Interview with Dawson Barrett

By Nick Juravich

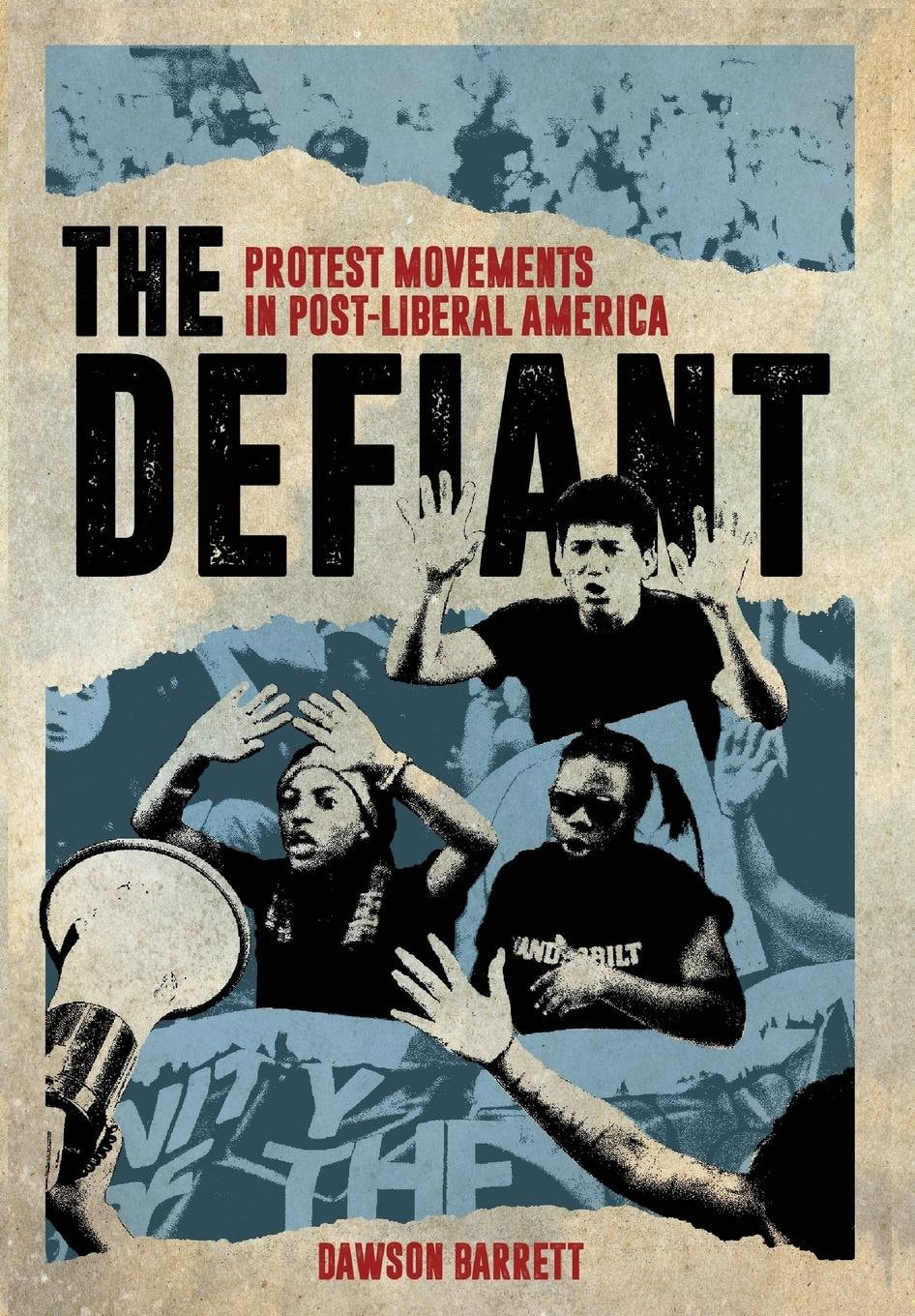

Today, I’m talking to Dawson Barrett about his new book, The Defiant: Protest Movements in Post-Liberal America, out now from New York University Press. The book has been getting some excellent coverage in the academic blogosphere recently; you can read an excerpt from the prologue over at Tropics of Meta, and a thoughtful interview that Dawson did with fellow UW-Milwaukee alum Joe Walzer for Labor Online. These two pieces, read together, are a great introduction to stakes, ideas, and arguments in The Defiant. Rather than recap them here at Gotham, we recommend checking them out.

Instead, my task is to ask Dawson about where and how New York City appears in The Defiant. At one level, this does a something of a disservice to the book, which nimbly analyzes a wide range of protest movements across the United States, from environmentalists in Arizona to farmworkers in Florida to students and teachers in Wisconsin.

However, as Dawson and Joe discussed in their Labor Online interview, by charting this “movement of movements,” The Defiant reveals the interconnectedness of struggles that are often studied separately. It also shows how diverse movements and actions are, in many ways, “expressions of protest against the same thing — crass greed that is destroying people’s lives and undercutting democracy.” The same is true when we tighten the frame. One of the joys of this book, for me, was connecting the dots not just across the country, but between diverse forms of organizing in New York City.

With all that in mind, I thought I’d start by walking through the three “New York moments” in the book, and then ask Dawson to reflect on some of the larger questions that arise when we look closely at protest in post-liberal Gotham.

The first look at a New York movement in The Defiant, and the longest and most in-depth, I believe, comes in Chapter 2, “Rebel Spaces: Youth, Art and Countercultures.” In this section, you dive into the world of all-ages punk collectives, using Berkeley’s 924 Gilman and the Lower East Side’s ABC No Rio as case studies. I loved this chapter, both as someone who played in high school punk bands and as a historian of NYC who loves to see understudied, bottom-up movements getting their due in the city’s top-heavy history (my very first post for Gotham was a review of Tamar Carroll’s Mobilizing New York, which does similar work). For the uninitiated, though, let’s start there: how did ABC No Rio find its way into a book about post-liberal protest?

Subcultural politics are often subtle or symbolic, and many scholars have built their careers trying to tease them out and connect them to broader socio-economic trends. My task was a much simpler one, as 924 Gilman Street and ABC No Rio, were (and are) overtly political spaces.

ABC No Rio. Photo by Dawson Barrett.

In addition to embodying the anti-capitalist ethic that flows through do-it-yourself punk rock, the folks running those venues announced openly (on their flyers and at the door) that racism, sexism, homophobia, and violence would not be tolerated — and, more importantly, they then confronted those behaviors when they appeared. These positions of course flew in the face of the contemporary policies of the Reagan, Bush, and Clinton administrations, and they weren’t just symbolic gestures. The Gilman and ABC punks routinely found themselves at odds (sometimes physically) with neo-Nazi skinheads, police, and even other punks.

I write in the book that punk rock is a form of direct action. That’s at its best. Punk as a whole actually has a pretty messy political history, full of contradictions and limitations. I don’t want to elevate it above any of the other important activist work included in (or neglected by) the book, but I do think it belongs in the conversation. It is not a coincidence that punk has been a consistently fertile organizing space for anti-fascist and anti-racist activism in many parts of the world. Street fights between Nazis and anti-fascists may feel very fresh to many Americans, but these clashes have been routine in the punk scenes of the US and Europe for decades.

It’s interesting for me to think about the book through the specific lens of New York, as the city’s residents have shaped so much of American protest politics, music, and art through so many different eras of US history. ABC No Rio is certainly a part of that important tradition. But I also could have told pretty similar stories about the 1980s and 1990s in the US through the lens of the punk rock scenes of, say, Davenport, or Tallahassee, or wherever.

To me, that makes ABC and Gilman more significant, not less. They are remarkably successful models, but they reflect something larger that was happening all over the country during that period. I come from a punk rock background, as well, and I played at dozens, maybe hundreds, of venues that were fairly similar to those two.

One thing this chapter captures so well is the way that countercultural spaces on the Lower East Side (and in similar urban neighborhoods across the country) straddle this transition from urban crisis to gentrification. How does ABC No Rio, as a collective, grapple with this transformation, which simultaneously trades on the idea of the LES as a cultural space and displaces bottom-up forms of cultural production?

That is another fascinating part of the story, and it speaks to the book’s larger purpose as a history of neoliberal capitalism. Democracy and capitalism are very often struggles over space — over who gets to use it and who gets to decide. In addition to staking out a countercultural position (in this case, counter to the period’s mainstream bigotry), ABC No Rio’s existence itself was inherently political.

Punk rock (much like the protest art scene that pre-dated it at ABC) isn’t popular enough (nor its patrons wealthy enough) to sustain, say, a concert hall. It finds its home instead on the margins — squatting abandoned warehouses, renting dilapidated storefronts, etc. This process often brings punks and other artists into contact with populations whose survival itself is precarious — and who, rightly or not, see these new arrivals as a harbinger of gentrification to come. This has been a common pattern in US cities, and in broad strokes, that is what was happening on the LES in the 1980s and 1990s.

Personally, I think much of the popular language around gentrification is pretty unhelpful (consider the toxic, often homophobic rhetoric on “hipsters” and “millennials,” for example), as it blames young people and artists with minimal means for the actions of banks and other speculators — and typically fails to take into account that they themselves can no longer afford to live anywhere, either.

In any case, the folks who founded ABC No Rio, to their credit, were acutely aware of how city policies helped landlords push out undesirable populations — and of their inadvertent roles, as artists, in the process. There is much more to that history, but ABC was a part of the movement that resisted the city’s evictions of squatters, artists, and homeless encampments from the LES during that period.

I think their story compels us to ask some important questions about privilege and accountability — and about how we can fight for the world we want to live in, while also coming to terms with the fact that we are still in the current one.

Since we’re a bunch of nerds, we love asking process questions. How’d you put this chapter together? What kinds of archives does a punk collective keep, if they do?

Subcultures are very difficult to document retroactively. I am currently working on a history of underground music in Peoria, Illinois (my hometown, about as far away, culturally, from New York as you could imagine) with journalist Jonathan Wright, and we have had to rebuild decades of history almost entirely through oral histories and faulty memories.

Because ABC No Rio and 924 Gilman Street are more like activist groups than just music venues, though, their “archives” include not only flyers and photos, but also meeting agendas, media clippings, and interviews with former members. Thankfully, members of each collective had already taken an interest in gathering some of these sources, providing a lot of the substance of the chapter and some really important leads. Over their three-plus decades of existence, clashes with authorities also landed the Gilman and ABC punks in the meeting minutes of local government agencies and attracted coverage in a range of media, including newspapers and several zines (self-published punk rock magazines).

Later, I was also able to follow up with members of each collective via e-mail, phone, and in-person interviews (and attend shows at each venue).

The next time NYC shows up in The Defiant is at the beginning of Occupy Wall Street and the occupy movement around the country. New York matters, in this case, not so much as the incubator of the movement but as the seat of “mafia capitalism” (as occupiers put it). I have two questions here, which go in slightly different directions. The first is about the occupation itself: What was it about occupying this heavily-policed, hyper-capitalized space that captured the national imagination? Following from that, what did the “occupy movement” do to and for this wider “movement of movements” that you explore in the book? (How much, in other words, does it matter? Is it one of many protest movements at this moment, or something more?)

Occupy Wall Street flier, 2011. Museum of the City of New York.

There was a lot of disingenuous commentary at the time, and those talking points are still parroted from time to time. The reality is that Occupy Wall Street quite clearly tapped into collective outrage at the banks that caused the recession and at the government that both enabled them and then bailed them out (including a growing disillusion with the Obama administration, which did not deliver on the hope and change that it promised). It was a revolt against neoliberalism, whether many participants would use that term or not.

Also, importantly, Occupy Wall Street was not just what happened at Zuccotti Park. As exciting as that was, much more significant was that that encampment inspired marches and occupations all over the world, including in small towns and cities throughout the US. I list many in the book, not because lists are fun to read, but because it is stunning how far Occupy spread.

Occupy had substantial public support, and thousands upon thousands of people who have never been to New York considered themselves part of a movement. Some were already involved in protest politics, but many were not. It’s because of that broad impact that we can see echoes of Occupy in so many subsequent struggles, from Black Lives Matter, to Standing Rock, to the Bernie Sanders campaign, to the high school walk-outs.

You mention the idea of New York as an incubator for movements — a hub of ideas, organizational know-how, funding, etc. And it has certainly been that for many of the important protest movements of the last century. New York activists have also provided leadership and inspiration. They have set the tone. During the Vietnam and Iraq peace movements, for example, New Yorkers’ protests were, predictably, among the earliest and the largest. That’s an important contribution that really has to be made in places like New York, Chicago, L.A., Washington, DC, etc.

But, for any kind of national political change, those ideas also have to resonate and become action in the Davenports and Tallahassees across the country. That is what happened with those two peace movements, and it is also the model we’ve seen repeated recently from Occupy Wall Street to the Women’s March to high school students’ March for Our Lives. And a significant protest in Davenport (which is in Iowa, by the way) is, of course, much smaller and much tamer than one in New York or Chicago. Movements, like organizers and teachers, have to meet people where they are.

The final “NYC moment” in the book is in the epilogue, which you start with the protests at JFK airport in 2017 after the announcement of the Trump administration’s travel restrictions. Given that the last two years have seen no shortage of protests responding to the administration, what about this particular one leapt out at you as you were wrapping up the project? Why did this story feel right for the epilogue?

Honestly, the main reason was that it was such a beautiful response to the rising politics of cruelty and culture of despair. Those protests brought tears of joy to my eyes. They were a reminder that humanity has its good days, too — days when we say, “Hell no!”

This is a book that tries to explain a pretty bleak moment in history — ours. It seemed reasonable to me to end with both a serious statement about what we are facing and a reminder that the future is not yet written. We have work to do.

Taking these three NYC protest movements together, one thing that leaps out immediately is the question of scale. So many of the protests you examine in the book are, in many ways, local, the efforts of a particular group in a particular place (like ABC No Rio). At the same time, the globalization of capital demands organized, globalized resistance, and the spread of protest movements through organizing and media (thinking here of Occupy) seems like a necessary response. How do the actors in your book navigate the challenge of working locally and globally? How much does place (whether in New York or elsewhere) still matter in the “global economy?”

Though it’s not a very long book, this was about a ten-year project, and my conclusion is that these struggles are even more connected than I had imagined. In one chapter, environmentalists, supposedly acting locally, have to build a global coalition to face their foe, and they are ultimately defeated by the actions of someone several thousand miles away. In another chapter, punks are connected by a worldwide network of touring bands and mail-order media. In another, college students pick fights with their schools in solidarity with farm workers many states away. In yet another, people protest to stop a war happening on the other side of the planet.

In short, there really is no such thing as “local.” People engage in the fight where they are, but they do not do so in isolation — even when they want to.

Beyond human connectedness, there’s another lesson in here, too. In this New Gilded Age of empire and monopoly, representatives of capital and the state — Wal-Mart, Amazon, Starbucks, ICE, or whatever (in the book, Taco Bell is one of several to play this role) — are everywhere. They are incredibly powerful, and we cannot seem to escape their reach! But, by being on every corner, they are also vulnerable on every corner. They cannot escape us either. Wall Street is in New York, but, you know, there was a Bank of America or a Wells Fargo in every town, just waiting to be occupied. Donald Trump may be in Washington or at Mar-a-Lago, but every city has an airport. There are many opportunities to apply pressure on the powerful.

You put the finishing touches on this book less than 18 months ago, and it feels like so much has happened since (as you and Joe discussed for Labor Online, your previous book, Teenage Rebels, has received renewed attention just this year in the wake of student-led protest against gun violence). If you were sitting down to write this book now, is there anything new you’d include?

Yes, a lot has happened! In book talks, I have been incorporating recent protest waves: the high school walkouts, teachers’ strikes, ICE protests, prisoner strikes, Kavanaugh protests, and others. I assume that I will have to keep revising my presentation. These are turbulent times.

If I had to add another chapter, I might do a deep-dive into the high school walk-outs, because I would like to draw out more on “gun rights” as de-regulation, as well as the connections to the US war industry and the political culture of fear. If I can squeeze one more point out of my Davenport bit, there were high school walk-outs this year in places where protests are essentially unheard of. I am excited to see what that means — what this generation of high schoolers are like in five years!

I feel pretty good about where the book ends, though. It’s intended as a tool, not an exhaustive study. My hope is that it provides, as is, enough that folks who read it (students, ideally) can then identify on their own the connections between privatized prisons and detentions centers, the de-regulation of fire arms, and cuts to public education — policies that are explored in slightly different forms throughout the book. Readers should also be able to understand recent protest waves as continuations of a long tradition. And — I think — they should also be able to make their own sense of how all of these things are related to the developing rift within the Democratic Party and the predicted split that did not materialize among Republicans.

These are a few of the questions that I think I can answer after researching and writing this book. I hope reading it provides similar benefits to others. Writing is certainly not a selfless act, but this book exists to try to explain something that I think is worth knowing, not to show off my intellectual chops.

Dawson Barrett is Assistant Professor of US History at Del Mar College in Texas. He is the author of Teenage Rebels: Successful High School Activists from the Little Rock Nine to the Class of Tomorrow (Microcosm Publishing, 2015) and The Defiant: Protest Movements in Post-Liberal America (New York University Press, 2018).