The Eight: An Interview with Albert M. Rosenblatt

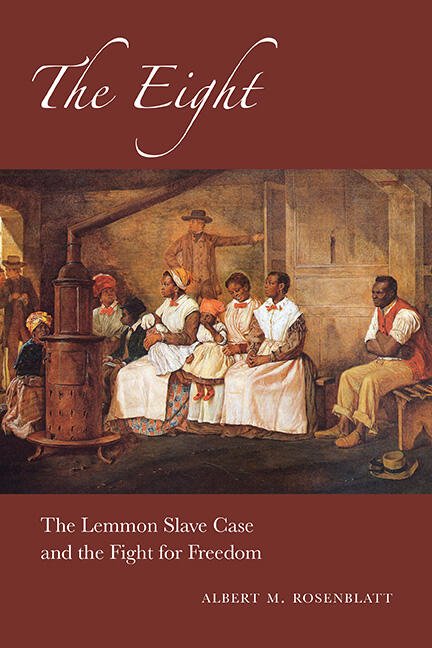

Today on Gotham, Evan Turiano interviews Albert M. Rosenblatt about his recent book, The Eight: The Lemmon Slave Case and the Fight for Freedom (SUNY Press, 2023). Rosenblatt spent three decades as a Judge in New York state courts, including several years on the New York Court of Appeals, the same court that heard Lemmon v. New York in 1860. He is currently a Judicial Fellow at the New York University School of Law. The Eight tells the story of the Lemmon slave case, a dramatic legal battle over the freedom of eight enslaved people who were brought to New York City while sailing from Virginia to Texas, at which point New York abolitionists initiated a freedom suit on their behalf. The eight-year legal saga that followed reflected escalating political tensions over the fate of American slavery and highlighted the legal contradictions that complicated a half-slave, half-free nation.

The interview has been edited for clarity and length.

I'd love to start by hearing a little bit about your personal relationship with the story, how you first encountered the Lemmon slave case, and why you set out to write a book about it. Can you talk about how your career and your work as a judge positioned you to write this book?

When I was on the court, the people around the building were faintly aware of the Lemmon case. We had an idea that Lemmon was well decided, and that it opposed Dred Scott, but very few people in the building knew what it was really about. It's like many other cases, such as Lochner v. New York or Wood v. Lucy, Lady Duff-Gordon, where we had a general idea, but no one knew all the details. I decided to read the decision, and took an interest in it beyond its abstract holding and its jurisprudence. Little by little, I became acquainted with the personalities of the Eight themselves, and particularly the heroics of the two moms, Emeline, who was only about 23 and Nancy, who was only 18 or 19.

A clear goal of this book was to capture the people involved, as you say, “not [as] eight legal entities, but eight real people.” How did you set out to do that research, and how did you adjust in response to challenges you faced?

The primary research on the Eight was not easy. I was able to research census records, marriage records, and any other family records of Billy Douglas, a slave owner who, in his will, left a number of slaves to Juliet Lemmon, including Emeline and Nancy. They came to Juliet by way of inheritance and gave birth to the others of the Eight. But it's very hard to identify them, even by name or let alone by birthdays or birthplace, because slave owners were not particularly careful about keeping records of their enslaved people. I begin one of the chapters by saying that Emeline's first appearance in the historical record is as one of several slaves without even a name. From that first appearance, little by little, with various records, I began to flesh out and make charts of the names of the Eight, with one very good stroke of luck. When Jonathan Lemmon and Juliet were on their way to Texas, and were diverted to New York by a quirk in travel plans, Jonathan stopped off at the office of a Justice of the Peace. In that office, he listed the Eight. Remarkably, that document exists. It is in the Buxton Museum in Canada, where I saw it over Labor Day weekend.

The central issue at hand in the case is this debate over the slaveholders’ right of sojourn, or the right to hold slaves in transit through the free states. It seems like that political issue often captures less attention than the question of the extension of slavery into the territories or the fugitive slave issue. Could you give an outline of the debate over the right to keep slaves in transit and why it was important in the national slavery debate?

Yes, most people are aware of the broader issues about ownership in human beings, and about the Fugitive Slave Acts of 1850 and 1793, and other congressional enactments which favored enslavement. But New York’s sojourning statute was also a pivotal piece in the Lemmon story. In 1817, when New York was in gradual abolition, the New York State Legislature enacted a statute allowing a nine-month sojourn of slaves. If people wanted to come up to Saratoga, Lake George, or New York City, for example, they could bring their slaves with them for up to nine months. But, interestingly, the legislature amended that in 1841 by striking struck the nine-month provision, so that in 1852, when the Lemmon case reached Judge Elijah Paine, he had before him a statute in which he could calculate nine months minus nine months, which is of course zero, meaning that the eight would be free the instant they set foot on New York soil.

With that background established, what were the major arguments laid before the court in the Lemmon case? What sort of arguments did each sides’ lawyers put forth, given the jurisprudential environment these laws established?

It was a hostile jurisprudential environment for African Americans. Among other reasons, because the United States Constitution contains the Fugitive Slave Clause, which still exists (although it's a dead letter now owing to the Civil War, the abolition of slavery, and the Thirteenth, and Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments). But in this environment, judges had to give back slaves found to be fugitives. Because of this, lawyers for Jonathan and Juliet Lemmon argued that Paine, as a New York judge, under the principle of conflict of laws, had no right to seize or confiscate property held by virtue of valid title under Virginia law. Their lawyers argued that Paine should accord full faith and credit to that title ownership, and should accord comity to the Lemmons. Additionally, they argued that if Paine were to discharge the slaves he would be violating the Commerce Clause, which, they argued, allowed people to cross state lines with their enslaved people.

The Eight’s lawyers, notably Erasmus Culvert and John Jay II, the grandson of the founder John Jay, argued that New York doesn't recognize ownership in people. Secondly, and most importantly, that the nine-month sojourn allowance was stricken and therefore slaves won their freedom the instant they arrived in New York. A fascinating argument followed. The Lemmon lawyers argued on behalf of the slave owners that the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, in addition to the United States Constitution, required that runaway slaves be returned to their “owners.” At that point in the transcript, Judge Paine stopped the lawyers and asked: “Were these slaves escaping?” I read this and thought, “Oh my goodness, this is one smart judge.” The lawyers said, “No, no, they weren't escaping.” It had occurred to the judge at that point that if the Eight were not fugitives, he was not required to return them to their owners under the Fugitive Slave Act.

That is a great transition to my next question, about Elijah Paine’s ruling. At the end of arguments and deliberation, Paine ruled the Eight discharged from service and thereafter free. How did Judge Paine couch his decision? And why do you think he did so in the way that he did?

He was too good of a technician to put it only on the loftiest of grounds. He made some natural law references, citing Grotius and Vattel’s political philosophies, but he didn’t place the decision primarily on those grounds. He placed it primarily on statutory grounds, saying, “The statute, and its 1841 amendment, calls for release of the Eight.” Additionally, he said that New York does not recognize property in human beings. Mostly, though, he strategically pitched it in a way that would make it more steadfast by basing it on the 1841 amendment to the 1817 statute, which struck the nine-month sojourning clause.

As your book tells well, the story doesn’t end with Paine’s ruling. It continues through a couple of appeals that play a role in a diplomatic crisis between Virginia and New York. By the time the final decision in the second appeal came down, campaigning for the 1860 election was well underway. How do you appraise the cases place in the 1860 election and the political crisis it created? Where do you see the Eight and their case’s place in the coming of the Civil War and the destruction of slavery that came with it?

When South Carolina seceded, several months after the Lemmon case came down in the spring of 1860, their Declaration of Secession said, essentially, “We have to leave the Union. We can't freely practice slavery anymore. And look at what these judges in New York had done, not even allowing us to pass through New York with our slaves!” South Carolina did not refer to the case by name, but of course, they were referring to Lemmon. And that speaks to the reaction of the South.

I want to end in the same place that your book does, by returning to the Eight as individual people. In your remarkable quest to track down their lives after the case, you ended up getting to speak with some of their surviving descendants. What was that like, and how did it help you humanize the historical actors in your book?

When I began, I never imagined that I would ever find any trace of the Eight. There were thousands who fled to Canada to escape slavery. I was able to make contact with Bryan Prince at the Buxton Museum. He’s an extraordinary historian who has the best set of records of people who came to Canada for freedom. When I first spoke to him, he knew of the Lemmon case but had not been able to find a trace of any of the Eight. The last we hear of them in the public record was a communication between John Jay and some folks in Buxton, who said, “Well, they're doing okay, not too great, but they're here.” That was in 1853, and they’re silent in the public record after that. So, before I sent the book off to the publisher, I thought I would try one more telephone call to Bryan Prince, and I asked him if he could give me a hint of a sliver of a morsel of an iota of a clue.

This time, he was able to tell me that he had a reason to think that one of the Eight—the seven-year-old twin boy, Lewis Wright—went to Michigan after the Civil War. That was major. I figured that even if there were hundreds of Lewis Wrights in Michigan, at least I had some place to start. Little by little, I kept on narrowing the search. And then one morning, probably in the wee hours, in a living room that looked like an accident scene with arrows all over the place, I told my wife Julia that I thought I found him. He had gotten married in Ypsilanti, Michigan after the Civil War. And once I had that, I was able—with a little bit of luck—to track his progeny through census records, marriage records, and the like. I tracked down seven generations and found a living offspring, and we had a wonderful conversation. Then, we did a Zoom call with the whole family, which was an experience I will never forget. It was joyous.

Evan Turiano is a Walter O. Evans Fellow at Yale University. He received his Ph.D. from the Graduate Center, CUNY. His first book, under advance contract with LSU Press, examines the contested legal rights of African Americans accused of being fugitive slaves from before the Revolution until the early Civil War. His dissertation was awarded the Bradford-Delaney Dissertation Prize by the St. George Tucker Society. His work has been supported by the New York Public Library's Lapidus Center, the John Carter Brown Library, the Massachusetts Historical Society, the Virginia Museum of History and Culture, and the University of Virginia's Nau Center for Civil War History.