The Gateway to the Nation: The New York Custom House

By Alexander Wood

The reign of Beaux-Arts architecture reshaped the landscape of the city at the turn of the century with grand public buildings that projected a new found sense of national power. The architects who embraced this style emphasized classicism, monumentality, and embellishment in their work, and were skilled at adapting historical precedents for modern building types. Following this mission to create civic symbols, Cass Gilbert conceived the custom house as a gateway to the nation. From its triumphal arched entry, and honorific statuary, to the heraldic imagery on its facade, it was expressly designed to evoke a passageway into a walled city. The allusion to a gate reflected a desire to proclaim the identity of the nation to the world, but it also suggested a point of controlled access through a border. It thus offered a suggestive precedent for the headquarters of the most important district of the federal customs service, which served as the guardian of the nation’s chief port of entry.[1]

Figure 1: U.S. Custom House and Bowling Green, 1908. Photograph. New-York Historical Society.

When it was completed in 1907, this massive granite edifice housed one of the most important institutions in the city. The custom house historically was the place where duties were collected on imported goods, and the new custom house was built to accommodate the growing complexity of this operation. It contained the offices of the presidentially appointed collector, naval officer, surveyor, and appraiser, and provided ample space for the army of clerical workers that worked within each office. The custom service’s primary responsibility was administering the tariff, but its broader mandate included policing the movement of goods, persons, and vessels into and out of the country. In total the building housed over 3,000 employees in 350,000 square feet of space, making it one of the largest office buildings in the city. [2]

From the beginning of the project Gilbert sought to create a monument that would command public attention on a prominent square. This monumental effect was achieved by the use of an overwhelming classical vocabulary that gave the building a colossal scale. To embellish the façade, he conceived a program of sculpture that proclaimed the nation’s emergence as a major world power. The triumphant tone is set with a giant cartouche depicting the shield of the nation, supported by two winged figures holding a sheathed sword and bundled reed. The sculptural program continues below with twelve heroic sculptures on the attic that represent imperial powers of world history, personified by warriors, military commanders, and monarchs. The most dramatic sculptures are the four female figures stationed at the front of the building, offering a reworking of the traditional allegorical theme of the four continents: America surges forth with torch in hand ready to liberate the world, and Europe presides as a wise ruler, while Asia sits in meditation next to a slave, and a nude Africa sleeps in the midst of ruins. The sculptural group offered a visceral appeal to a racialized view of the world. Like a triumphal victory arch, the facade glorified the subjugation of native peoples at home, and the justified the mission to civilize “savage” peoples abroad.[3]

Figure 2: Rotunda, U.S. Custom House, 1937. Franklin D. Roosevelt Library.

The large arched entryway at the center of the façade gave a ceremonial quality to the passage up the stairway to the ground floor where the public transacted its business. The focal point was the great elliptical rotunda located in the center of the court. Under the dome, masters entered their vessels by submitting their manifest, and verifying this manifest by oath in the presence of officers, before a permit to discharge was granted. Masters clearing their vessels filed a sworn manifest of their outward lading described by kind, quantity, value, and destination, before a clearance and a bill of health were issued. Meanwhile, importers, and licensed brokers worked with other officials to release their goods. The ground floor was a scene of great commotion, and as one observer noted, it required enormous patience “to unravel those coils which bind the goods that enter this port in a maze of red tape.” [4] Beyond public view, the rest of the building up to the sixth floor was filled with the offices of a sprawling bureaucratic machine that carried out a wide array of fiscal, regulatory, and statistical duties.[5]

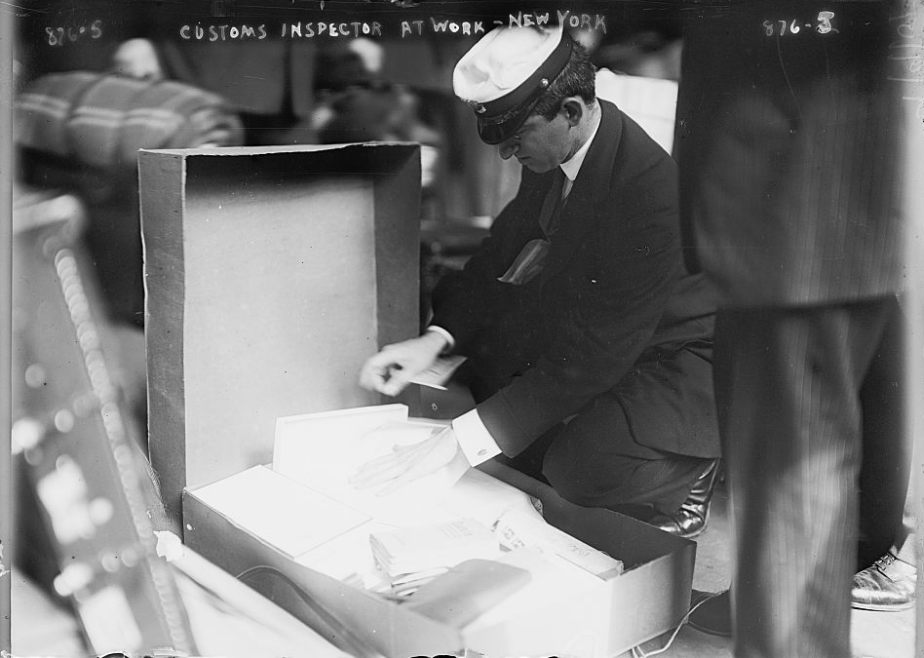

Figure 3: Customs Inspector at Work, NDL pier, New York, 1909. Library of Congress.

On a given day the customs service processed the entry of fifteen vessels, from the big English, French, and German liners, to smaller freight steamers, and sailing ships. Once a ship entered the port they were under the charge of the surveyor’s office, which was organized into five divisions that handled the inspection, weighing, and measuring of all goods entering the port. In 1908, the first year after the building’s completion, the customs service entered over 4,500 vessels from over thirty different countries carrying eight hundred million dollar’s worth of goods. The principal sources of this commerce was Europe and its dependences around the world, followed by Latin America, and rounded out with commerce from Japan, China, and the nation’s new insular colony in the Philippines. The principal articles entering the port were raw materials, foodstuffs, and partially manufactured goods. The city received three-fourths of the country’s coffee, sugar, and cocoa, and nearly half of the tobacco and tea. It received more than three-fourths of silk, cotton, and wool manufactures. In addition, it received 90 per cent of the India rubber, books, diamonds and precocious stones. In the course of a calendar year over half of the nation’s foreign trade in value entered the port.[6]

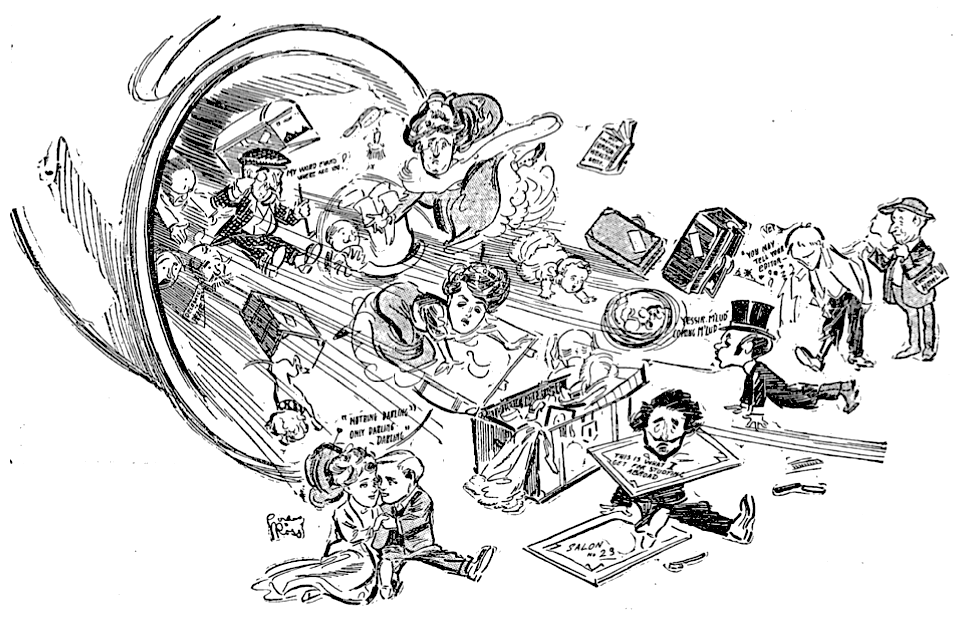

Figure 4: Coming Through the New York Custom House. New York Times (April 28, 1907), SM5.

In the period in which the custom house was built its officers administered the highest protective tariff in the nation’s history, reaching nearly nearly fifty percent on dutiable goods. The complex task of determining the specific duty on goods fell to the appraiser’s office, which was divided into ten divisions. To each division was assigned an extraordinary range of goods which needed to be carefully examined before they could appraise their market value at the time of exportation. In the Fifth Division, for example, a journalist noted that the assistant appraiser was responsible for appraising a remarkably wide range of merchandise. “We find that his attention is distributed over artificial flowers, bird skins, and quills for millinery, carpets, corsets, dog skins dressed, down quilts and pillows, gloves and armlets, India rubber tubing for flowers, all rugs, knitted underwear and forty or fifty other things.”[7] More than anything, the customs house was a revenue producing machine. The hundreds of millions of dollars which passed into its coffer’s each year formed a large percentage of the national revenue.[8]

For the most part the public was only dimly aware of the scale of this operation, and its own experience of the customs service was extremely unpleasant. Shortly after the completion of the custom house the customs service instituted a new inspection regime for all incoming passengers. While still on board, every person entering the port was required to declare under oath all goods that were dutiable, and as one journalist put it, “leave the rest to luck, their conscience, and the Customs Inspectors.”[9] After landing, they were patted down, their trunks were opened, and their baggage inspected. In a cartoon that summed up the experience of going through customs, passengers are depicted being thrown out of a chute, dazed as to what just happened. The loudest outcry came from wealthy tourists laden with luxuries purchased abroad, but it was an experience that offended citizen, tourist, and immigrant alike. A returning traveler noted that the “whole disagreeable farce in which he figures makes him feel like a thief and a fool; and he cannot even laugh at its absurdity, because he is the victim of the joke.”[10] Meanwhile, as another critic explained, “[t]he well-to-do foreign tourist …encounters what he considers this barbarous custom of prying into the secret belongings of retiring, shrinking citizens.”[11] The regime came down hardest on the immigrant, who was subjected to this procedure within the confines of the imposing immigration station. “The immigrant, seeking a land of freedom, is amazed when he sees that before he can really breath the air of this free land he must pass through iron bars and cages that resemble nothing so much as a prison.”[12]

From his perch in the monumental new headquarters, the collector rejected these pleas. As the gatekeeper of the port, he was entrusted with the solemn duty to protect the revenue. “We will not hesitate to strip a passenger to the skin if we consider it necessary to prevent smuggling,” he proclaimed.[13] “It is within the legal province of the government to search every person who enters this country if our suspicions are aroused, and no good citizen should object to Uncle Sam getting his rights.”[14] Today the custom house is a cherished architectural landmark, but when it was built it was a fearsome symbol of federal authority over the port and of the high tariff wall that surrounded the nation.

Alexander Wood is a Ph.D. candidate at Columbia University, where he studies the history of American architecture, urbanism, and landscape.

Notes

[1] Samuel Stockvis, The Gateway to the Continent: The Customs Service of the Port of New York (New York: 1900), 1-25; The history of the U.S. Custom House competition is addressed in Sharon Lee Irish, “Cass Gilbert’s Career in New York, 1899-1905,” Ph.D. diss., Northwestern University, Evanston, 1985, 256-322.

[2] “New York’s Custom House,” New York Times (November 14, 1909), XX4.

[3] “Cass Gilbert’s New York Customhouse Design.” The Inland Architect and News Record 35 (February 1900): 6-7;.“Daniel Chester French’s Four Symbolic Groups for the New York Custom House,” The Craftsman 10 (April, 1906); 75-83.; Michele Bogart, Public Sculpture and the Civic Ideal in New York City, 1890-1930 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989), 111-134.

[4]Charles De Kay, “The New New York Custom House,” The Century 49 (March, 1906): 739.

[5] “The New Custom House: Interior of the Building That of a Business Structure,” New-York Tribune (October 6, 1907), A2..

[6] Figures taken from Annual Report of the Corporation of the Chamber of Commerce, of the State of New York, vol. 51, Part II (New York: Wheeler and Williams, 1909), 106-146; and Annual Report of the Secretary of the Treasury on the State of the Finances (Washington, D.C.: 1909), 171.

[7] “New York’s Custom House,” New York Times (November 14, 1909), XX4.

[8] Seth Low, “The Position of the United States Among the Nations,” 11; Douglas A. Irwin, Clashing Over Commerce: A History of U.S. Trade Policy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017), 6.

[9] “Coming through the New York Custom House,” The New York Times (April 28, 1907), SM5.

[10] Agnes Repplier, “Pity the Persecuted,” Life 52 (July 10, 1908), 1974.

[11] “Collection of Customs: How it is Done,” New York Times (August 25, 1901), SM9

[12] Ibid.

[13] “Customs Complains Nonsense, Says Loeb,” New York Times (September 5, 1909), 6.

[14] Ibid.