The Men Who Helped Get Women the Vote

By Brooke Kroeger

On May 6, 1911, under perfect blue skies, ten thousand spectators lined both sides of Fifth Avenue “from the curb to the building line” for the second annual New York Suffrage Day parade. Somewhere between three thousand and five thousand marchers strode in a stream of purple, green, and white, from Fifty-Seventh Street to a giant rally in Union Square. Bicolored banners demarcated the groups by their worldly work as architects, typists, aviators, explorers, nurses, physicians, actresses, shirtwaist makers, cooks, painters, writers, chauffeurs, sculptors, journalists, editors, milliners, hairdressers, office holders, librarians, decorators, teachers, farmers, artists’ models, “even pilots with steamboats painted on their banners.” Women’s work was the point. The New York Sun repeated the entire list at the top of its front-page story.

This excerpt from The Suffragents: How Women Used Men to Get the Vote

is reprinted by permission of Excelsior Editions, an imprint of SUNY Press.

To draw broad attention for this spectacle, the women had help from a single troupe of men in their midst — eighty-nine in all, by most accounts — dressed not in the Scottish kilts of the bagpipers or the smartly pressed uniforms of the bands, but in suits, ties, fedoras, and the odd top hat. They marched four abreast in the footsteps of the women, under a banner of their own. These men were not random supporters, but representatives of a momentous, yet subtly managed development in the suffrage movement’s seventh decade. Eighteen months earlier, 150 titans of publishing, industry, finance, science, medicine, and academia; of the clergy, the military, of letters and of the law; men of means or influence or both, had joined together under their own charter to become what their banner proclaimed them, the Men’s League for Woman Suffrage. Since the end of 1909, they had been speaking, writing, editing or publishing, planning, and lobbying New York’s governor and legislators on behalf of the suffrage cause.

They did so until the vote was won.

Among the League’s most notable members and fellow travelers were George Foster Peabody, Max Eastman, Oswald Garrison Villard, John Dewey, Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, Frederick Nathan, George Creel, George Harvey, James Lees

Laidlaw, Norman Hapgood, and fellow travelers such as Dudley Field Malone and W.E.B. Du Bois. Many of their names resound through history as political kingmakers and promoters of such progressive causes as civil rights, child welfare, the educational advancement of black Americans, and, later, disarmament. They were leaders or members of celebrated organizations like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the People’s Institute, with its mission of “teaching the theory and practice of government and social philosophy

to workers and recent immigrants.” A number of them would be among those in Woodrow Wilson’s circles. But on this day in the spring of 1911, they had gathered for the sole purpose of pressing for the right of women to vote.

American men as individuals had publicly supported the rights of women as far back as 1775, when Thomas Paine published his essay, “An Occasional Letter on the Female Sex.” After the Seneca Falls Convention to support women’s rights in 1848, other men wrote more specifically in support of women’s enfranchisement, notably William Lloyd Garrison, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Frederick Douglass. In England, John Stuart Mill’s The Subjection of Women, published in 1869, echoed many of the arguments that his wife, Harriet Taylor Mill, had presented in “The

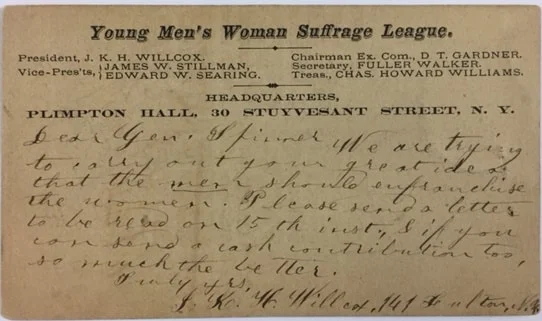

Enfranchisement of Women,” eighteen years earlier. And briefly, between 1874 and 1875, a Young Men’s Woman Suffrage League met in New York City, fielding pro-suffrage speakers from its membership — physicians, attorneys, and professors among them — at some eighty meetings in the Plimpton Building at 30 Stuyvesant Street in what is now the East Village.

Yet to take on the cause of women’s suffrage was almost always to do so at a price, especially for men. So it was on the parade line in 1911, where the men endured what, for the times, were unforgettably pernicious assaults on their masculinity. “Hold up your skirts, girls!” rowdy onlookers shouted. “You won’t get any dinner unless you march all the way, Vivian!” For all two miles of the walk, a newspaper clipping recounted, the men submitted to “jeers, whistles, ‘mea-a-ows,’ and such cries as ‘Take that handkerchief out of your cuff.’”

In the last decade-long lap of the suffrage fight, the mockery of 1911 would give way to a more muted, sometimes ironic response to the men who took up the cause. In time, male suffragists would become commonplace — and then, all but forgotten as an orchestrated movement force.

This is not so surprising. The story of the triumph of the suffrage cause has long belonged to the women, and rightly so. In the century since New York State granted women the vote in November 1917, strikingly few details about the

men’s efforts have thus emerged. No known source to date examines in depth the origins, mission, or growth of the Men’s League for Woman Suffrage, which ultimately stretched to include thousands of adherents across thirty-five states and other parts of the developed world.

At points during the battle and after it was won, the women of the organized suffrage movement recognized the sizable contributions of their elite male allies. The official account of the period, Ida Husted Harper’s The History of the Woman Suffrage Movement, recalls the “invaluable help” the men provided and acknowledges the “influential factor” they became during crucial votes in the New York legislature. It acknowledges the abundant prestige they lent. Yet even in this multivolume chronicle, reference beyond these few comments is scant. We get little more than some of the men’s names, along with a misdated reference to the valor the men of the New York league demonstrated during the 1911 parade.

...

From a contemporary standpoint, it is remarkable to consider that one hundred years ago, these prominent men — highly respected and influential, their exploits chronicled regularly in the national media — not only gave their names to the cause of women’s rights or called in the odd favor, but rather invested in the fight. They created and ran an organization expressly committed to an effort that, up until the point at which they joined, had been seen as women’s work for a marginal nonstarter of a cause. From the beginning of their involvement, these men willingly acted on orders from and in tandem with the women who ran the greater state and national suffrage campaigns. How many times in American history has such collaboration happened, especially with this balance of power?

This episode in the suffrage epic provides a means of observing the shift in the common perception of the suffrage movement as a whole. It also demonstrates the strategic brilliance of a decision by leaders in NAWSA, the National American Woman Suffrage Association, the main suffrage organization in the United States, to cultivate relationships with the well-heeled and the well-connected — women as well as men. In this period, Katherine Duer Mackay, wife of Clarence Mackay, of the AT&T Mackays, and Alva Smith Vanderbilt Belmont, widow of the businessman and politician O.H.P. Belmont, formed and presided over influential prosuffrage societies. Dashing prosuffrage couples of the period were Laidlaw, the financier who was on the board of directors of what became Standard & Poor’s, and his wife, Harriet Burton Laidlaw; Nathan, the wealthy scion of an important Sephardi

Jewish family, and his wife, the social activist Maud Nathan, his first cousin, also born a Nathan; Narcissa Cox Vanderlip and her husband, Frank A. Vanderlip, who was the president of the National City Bank of New York were deeply involved, as were Vira Boarman Whitehouse and her husband, the stockbroker James Norman de Rapelye Whitehouse. In short order, the media attention they attracted brightly burnished the movement’s image in the mainstream press.

Over the course of these crucial years, the staunchly antisuffrage editorial stance of such newspapers as the New York Times and the New York Herald bled a little less heavily onto their news pages. Editorialists, especially at the Times, took longer. As the Men’s League emerged in New York, and was rapidly cloned in city and county chapters across the state and well beyond, the mocking derision and dismissiveness that initially dominated coverage of the “Mere Men” in particular, and of the suffrage movement more broadly, gave way to acceptance of an idea whose time was about to come.

The men of New York were not the first to organize. In Britain, male supporters of the women’s vote formed the first known men’s league in 1907. Men in Holland organized in 1908. On this side of the Atlantic, prominent men in

Chicago created a league in January 1909, ten months ahead of the New York chapter’s first formal meeting in November. Nonetheless, New York is hallowed ground for the women’s movement in the United States. It is the geographical home of Seneca Falls, site of the landmark convention long credited with bringing the suffrage movement into being. Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, the two most revered names in the movement’s history, are daughters of the Empire State. As the country’s undisputed media capital, much of the vital

journalism, creative writing, speechifying, and pamphleteering for and about the movement emanated from Gotham’s publishing precincts. And by 1909, thanks to new financial support from wealthy society matrons supporting the cause, NAWSA at last had the wherewithal to establish impressive headquarters in New York City at precisely the moment the Men’s League was being founded in Max Eastman’s Greenwich Village apartment.

In addition, the dazzling pageantry, cleverly targeted recruitment gimmicks, and regimental campaign operations of these years were both New York–born and New York–borne creations in which the men joined as full partners. As

the movement grew in strength and acceptance, its important new champions attracted beneficial press, whether they gave speeches, appeared at marches or at social gatherings, worked the halls of influence in Albany and Washington, or crafted or published buzz-worthy essays or attention-getting diatribes in the form of letters to the editor.

Beyond the arc of change in press coverage and public perception, it is worth noting other aspects of the male suffragists’ lives. For one, there are the personal relationships that motivated them to take up what in 1908 was still widely viewed as a laughably unimportant cause. Standing for the rights of workers was surely a factor for reformers like Eastman. His sister, Crystal Eastman; his girlfriend for part of this period, Inez Milholland, who remained a close friend; and his first wife Ida Rauh, were all deeply involved with the labor reform movement,

notably the shirtwaist workers strike of 1909–1910. Unsurprisingly, behind nearly every one of the men who put the most energy and time into the suffrage movement was an ardent movement activist (or two, or three, or four) who, as in Eastman’s case, also happened to be his wife, his mother, his sister, or his love interest. Daughters could also prove persuasive, as evidenced by the involvement of John Milholland, father of Inez, and ultimately by the evolving position of President Woodrow Wilson, two of whose daughters, Margaret and Jessie, were known to be prosuffrage.

Worth appraisal, too, is the strategic decision of NAWSA President Anna Howard Shaw and her colleagues, after a long period of reluctance, to solicit or embrace the offers of support from these particular new allies. NAWSA did this assuming that participation was likely to be nominal. Shaw asked little. Yet the new male activists, like their society lady counterparts, gave of themselves far beyond what NAWSA’s leaders had expected. In fact, before too long, these dignified gents showed a surprising willingness to don costumes, act, dance, and work the streets. They attended city, county, state, national, and international meetings. They joined delegations and hosted lavish banquets. They lobbied at the state and national levels and issued loud, formal, headline-producing protests when the police in New York and Washington mistreated marchers or left them unprotected against the onslaught of catcalling, brick-batting mobs. The lawyers among them stepped up to represent the women suffragists who wound up in court.

Robert Cameron Beadle, secretary of the Men’s League of New York after Eastman, rode horseback from New York to Washington, DC, with a women’s equestrian delegation. The Nathans and Laidlaws made statewide automobile

recruitment trips. On separate occasions, the two couples went national, traveling out West to work on separate state suffrage campaigns.

As Shaw had presumed would happen, the planning minutiae and execution of the men’s involvement in major events often fell to the women. That the women accepted this without apparent disappointment or rancor is unsurprising. Logistical and administrative tasks must have seemed a minor encumbrance given the potential of high-level, highly useful male participation in the cause.

Of course, in this period there were also vocal male detractors from the same professional and editorial classes. Pearson’s and Ladies Home Journal commissioned major antisuffrage investigations by the journalist Richard Barry that in turn brought a barrage of published rebuttal. Men’s antisuffrage groups formed in reaction, but with not nearly the staying power, constancy, support, or impact of the male forces that supported the cause. And yet more than once, an invited male speaker— including a sitting president — stunned his hosts and audiences by speaking publicly against women’s suffrage at movement-sponsored events.

With few exceptions, it is also evident from the relative paucity of references to suffrage in the biographies, autobiographies, and personal correspondence of the Men’s League’s influential founders — Peabody, Wise, and Villard in particular — that local, state, and national elections, affairs of state, and civil rights took clear precedence over suffrage on their agendas. This was true even at moments when suffrage was as big a front-page story.

All the same, real support was offered and real support was meant, felt, and acted upon. This was especially apparent during the two years of focused campaigning that led to the climax of the story this book tells: the New York legislative and voter victories of 1917. Who else but the prominent men among the movement’s declared backers had such ready personal access to the — also male — state and federal legislators and government leaders, to publishers, or to the editorial elite? It worked to the movement’s extreme advantage that so many League members and leaders were themselves publishers and the editorial elite. Twice, Eastman sparred publicly with Theodore Roosevelt. At various points, Peabody, Villard, Wise, Creel, Harvey, Hapgood, Malone, and Eastman all had Woodrow Wilson’s ear. Most of them were among Wilson’s earliest political backers; Eastman had his respect. Creel, in the critical period when Wilson at long last came out in favor of the federal suffrage amendment, was on “terms of intimacy” with the president, meeting with him almost daily in his capacity as chair of the Committee on Public Information after the United States entered World War I in 1917.

No doubt an accumulation of other factors, far greater than the Men’s Leagues, led to the ultimate success of the women’s suffrage campaign: seven long decades of effort by passionate women, the changing times and political winds, the burgeoning public support, the growing number of states where women with the vote could influence outcomes; the movingly sacrificial role women played after the United States entered World War I. Still, once the details are known, it is hard to ignore the boost that the men provided. Their involvement amounted to more than an “influential factor” or “invaluable help.” Much more. Their commitment showcases the value elite individuals who act with care can bring to marginalized movements, particularly those with social justice aims. The impact

of Men’s League actions a century ago speaks loudly to the strategic importance of cultivating people with influence and magnetic media appeal, those who can attract positive public attention, open access to those in positions of power, and alter public perception.

It was a major departure for men of such stature to decide that it mattered for women to vote, to recognize that as a chartered prosuffrage organization, men could wield influence in ways that women could not, and to understand that to make a difference, they would be required to offer more than an early twentieth century equivalent of a celebrity endorsement or a goodwill ambassadorship — the kinds of gestures we see most often today. The founders of the Men’s League knew that to help sway the course of history, they needed a full-fledged national, then multinational organization, with all the effort and expense that implied. They needed an entity in which men of great standing would subordinate themselves to women in a women-driven enterprise devoted to a “women’s cause,” and would claim center stage only when called upon or needed to do so. For that is exactly what happened.

Brooke Kroeger is a professor of journalism at New York University. Her latest book, The Suffragents, chronicles the prominent, influential men whose support helped women get the vote.