The Notorious "31 Women" Art Show of 1943

By Marjorie Heins

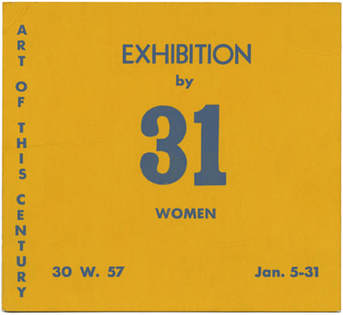

The art collector Peggy Guggenheim had just opened her avant-garde "Art of This Century" gallery on West 57 Street in the fall of 1942 when her friend Marcel Duchamp suggested that she mount an all-woman exhibition. Guggenheim loved the idea: the show would be radical not only because of its composition but because most of the paintings, drawings, and sculptures on view would be either abstract or Surrealist in style, as befitted Guggenheim's modernist taste.

Leonor Fini's "The Shepherdess of the Sphinxes"

Leonor Fini's contribution, a painting called "The Shepherdess of the Sphinxes," drew on classic Surrealist themes of sexuality and, in this case, female power: it depicted a scantily-clad, voluptuous shepherdess in a dream landscape filled with equally voluptuous sphinxes who seem to have been feasting on bones and flowers. (It's now at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice.) Surrealist Kay Sage's painting, "At the Appointed Time," depicted a more abstract nightmarish landscape dominated by an ominous vertical metallic pillar, a road leading nowhere, and slimy, snakelike forms crawling over two horizontal beams.

Newcomer Dorothea Tanning's "Birthday" showed a half-undressed young woman standing beside a seemingly infinite series of receding doors; a birdlike monster lies at her feet. Tanning's work was chosen by the celebrated European Surrealist, Max Ernst, then married to Guggenheim; she had assigned him the task of visiting the studios of promising female artists in order to choose likely candidates for the upcoming show. Ernst, a notorious womanizer, promptly left Guggenheim and moved in with the much younger Tanning.

Georgia O'Keeffe declined an invitation to participate in the show, saying that she refused to be categorized as a "woman painter." She could afford to be particular, having by this time attained substantial recognition on her own. Other female artists did not have this luxury -- several, like the sculptor Xenia Cage, labored under the shadows of their more famous husbands (in her case, the composer John Cage); others, like the painter Buffie Johnson, knew plenty about sex discrimination in the art world (Time magazine critic James Stern had bluntly refused her request that he review the show, observing that women should stick to having babies).

Those critics who did review "31 Women" greeted it with a mixture of grudging admiration and dismissive condescension. The New York Times reviewer, Edward Alden Jewell, damned the show with faint praise and a patronizing tone. First, he made fun of the unconventionally undulating walls and biomorphic furniture in Guggenheim's gallery; then he mocked Louise Nevelson's "Column" ("you would call it sculpture, I guess," he wrote). But he did note that "the exhibition yields one captivating surprise after another."

"H.B.," the critic for Art Digest, wrote in a similar vein: "Now that women are becoming serious about Surrealism, there is no telling where it will all end. An example of them exposing their subconscious may be viewed with alarm at the Art of the Century headquarters during January."

The worst of the put-downs came from Henry McBride in the New York Sun: women Surrealists were actually better than men, he said, because after all, "Surrealism is about 70% hysterics, 20% literature, 5% good painting and 5% just saying boo to the innocent public. There are, as we all know, plenty of men among the New York neurotics but we also know that there are still more women among them. Considering the statistics the doctors hand out, and considering the percentages listed above, … it is obvious women ought to excel at Surrealism.”

A final critic, in Art News, likewise could not resist snarky asides, but also raised serious questions about the wisdom of mounting woman-only shows. "Division of the sexes, or rather segregation of the female of the species, is ordinarily a dubious policy for an art show," the anonymous R.F. wrote; "but this time, however, there is no outbreak of watercolor or flower paintings. The women -- they could never be laughingly referred to as ladies -- present a chinkless armored front." Women artists in 1943 evidently were damned either way, whether for creating presumably unimportant watercolors and flowers, or for being Amazons.

The condescending rhetoric of the reviewers in 1943 is largely out-of-date today, but the problem of underrepresentation of women in major art collections remains. On a recent day (in January 2016), I counted the works by female artists in the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Modern and Contemporary Art galleries. There were 29 -- as opposed to 305 works by men. That's about 9.5 percent, up from the less-than-5 percent total reported by the advocacy group Guerrilla Girls in 1985. Still, it's not very many.

"31 Women" attracted attention in part because one of its artists was the popular vaudeville stripper Gypsy Rose Lee, who was also a writer and a denizen of bohemian cultural circles. Her contribution was a collage titled "Self-Portrait" (she was clothed). The more serious, full-time artists included the up-and-coming abstract sculptor Louise Nevelson and the Surrealists Frida Kahlo, Leonora Carrington, Leonor Fini, and Meret Oppenheim, whose work, a teacup and spoon covered in fur, had caused gasps when it was shown at the Museum of Modern Art's "Fantastic Art" exhibition seven years before.

Kahlo was already famous, in part because of her marriage to the painter Diego Rivera, who had refused to comply with John D. Rockefeller, Jr.'s demand in 1933 that Rivera remove an image of Vladimir Lenin from his mural at Rockefeller Center. (Rockefeller then had the mural destroyed.) Kahlo's contribution to "31 Women" was a pencil drawing, "Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair." Dressed severely in men's clothes, with her shorn hair on the floor around her, Kahlo's grim self-portrait was a response to Rivera's chronic infidelities.

Guerrilla Girls poster, 2015

Buffie Johnson was sufficiently incensed by the sexism of the Time critic who thought women should stick to having babies that she wrote an article on women artists of the past, and the often insurmountable hurdles they have faced. She could not find a publisher for it until 1997, when the Jackson Pollock-Lee Krasner House in East Hampton, Long Island, mounted a show commemorating "31 Women" and a second, 1945 all-woman exhibit at Guggenheim's gallery. The catalog that accompanied the Pollock-Krasner House show included Johnson's article.

Buffie Johnson's contribution to "31 Women" back in 1943, incidentally, was a painting called "Dejeuner sur mer," a seascape with two women clinging to a wreck.

* Other artists represented in "31 Women" were Djuna Barnes, Irene Rice Pereira, Hedda Sterne, Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Hazel McKinley, Pegeen Vail, Barbara Reis, Valentine Hugo, Jacqueline Lamba, Suzy Frelinghuysen, Esphyr Slobodkina, Maria Helena Vieira da Silva, Aline Meyer Liebman, Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, Julia Thecla, Sonia Secula, Gretchen Schoeninger, Elizabeth Eyre de Lanux, Meraud Guevara, Anne Harvey, and Milena Pavlović Barili, who is not well-known around the world but is a hero in her native Serbia: several of her works were reproduced on Yugoslavian postage stamps.

Marjorie Heins is a writer, lawyer, and volunteer tour guide at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. She is the author of Sex, Sin, and Blasphemy: A Guide to America's Censorship Wars and Not in Front of the Children: Indecency, Censorship, and the Innocence of Youth, among other works.