The Old Boys’ (Lunch) Club: Sharing Meals and Making Deals on Gilded Age Wall Street

By Atiba Pertilla

Howard Russell Butler portrait of William Allen Butler, Jr., Princeton University Art Museum

William Allen Butler, Jr., the founder of downtown Manhattan’s Lawyers Club, would later explain that its creation was inspired by a disturbing encounter. One afternoon in the 1880s, he went out for lunch with his father and partner, William Allen Butler, Sr.—a respected corporate lawyer, son of a former U.S. Attorney General, and co-founder of the Association of the Bar of the City of New York. The restaurant was crowded, but moments later an office boy from his law firm finished lunch and “my respected father occup[ied] that same stool to order a slice of roast beef.”

Unable to find a seat for himself, the younger Butler ended up standing at the restaurant’s “oyster counter” and swallowing down a sandwich “of the genus warranted to stand on one’s chest for a couple f hours.” He found the blurring of class boundaries and the uncomfortable conditions troubling, wondering “Was there not some better way for the noon-day hour luncheon?” His conclusion was that there was a need for “a reputable and decent place” where men like himself and his father could enjoy a decent midday meal in private, dignified surroundings, away from their subordinates.[1] He decided, in short, to establish a lunch club.

Lunch clubs were an important component of the social infrastructure of Wall Street in the late Gilded Age. Yet they have gone largely unnoticed ever since. Often located in specially designed spaces in the financial district’s new skyscrapers, they were organizations with large memberships where businessmen could gather for a high-quality meal, far from the crowds and noise of restaurants open to the general public. Most studies of elite club membership have focused on social clubs and country clubs, typically located in residential neighborhoods, places where members affirmed their privileged status through conspicuous consumption (drinking proprietary cocktails, reading first editions in well-stocked libraries, playing golf and tennis or squash and racquetball…). Such clubs often reinforced the orientation towards expensive leisure with explicit or implicit rules barring the discussion of business or the display of related documents.[2] This is where the Wall Street lunch clubs differed. They offered members a similar respite from the office. But from the start they were places that combined luxurious consumption with productive business. Examining elite lunch clubs provides insight into how making and re-making connections with one’s peers was an important component of the Wall Street professional’s workday routine.

The lunch club was a relatively recent innovation in New York City, established in the years just after the Civil War to serve prosperous men who spent a full workday downtown and did not want to pay for meals at expensive restaurants like Delmonico’s in order to enjoy high-quality food. Manhattan’s first lunch club, the Down Town Association, located on Pine Street, was originally established by merchants and other men whose business revolved around the activities of the New York seaport, a short distance away. The Merchants Club had been established in 1871 by dry goods dealers, but was located in their business district, just north of City Hall. By the 1880s, the Down Town had developed a reputation for snobbishness and an impractically long waiting list, while the Merchants Club was a place where “older partners in prosperous concerns” went to “take things easy” on the fringe of the financial district.[3]

Delmonico’s, date unknown (c. 1890–1917): Robert L. Bracklow Photograph Collection, New-York Historical Society. This photograph depicts the entrance to Delmonico’s, arguably New York City’s most prominent restaurant in the 19th century

Waiters standing in the main dining room of the Down Town Association, Pine Street, 1902: Byron Collection, Museum of the City of New York. The Byron Collection includes several other behind-the-scenes photographs of the Down Town Association.

Thus, when Butler decided to create a lunch club, he sought a place where the men who worked in and around the multiple financial institutions and law firms that clustered on and near Wall Street could mix business with expensive dining. He soon found several other attorneys who supported the idea of establishing a gathering place for their profession, and reached agreement with the Equitable Life Assurance Society to house the club on the fifth floor of its headquarters at 120 Broadway. In 1887, the club formally opened with 346 members and quickly attracted not only lawyers but also stockbrokers like Edward Shearson, accountants like A.L. Dickinson of Price, Waterhouse & Co., and other professionals in the financial district’s new skyscrapers. By 1901 it had more than 1,000 members. More than 500 people lunched there on a typical weekday. Several other lunch clubs opened in the 1890s and 1900s, often, similarly, taking space in an office building’s upper floor. The City Midday Club, for example, whose founders included attorney Paul D. Cravath, was established in 1901 on the twentieth story of 25 Broad Street and offered “merchants, lawyers and financiers” an “exclusive place” for lunch and “a chance to talk over their business matters together.”[4]

The new lunch clubs drew the interest of contemporary journalists, who described them to readers in magazine articles with titles like “Deals Across the Table,” chronicling the activities of the professionals who consolidated large industries and channeled millions in bonds towards such things as railroad construction. The “depressing spectacle of a prosperous man… at some rushing lunch-counter, gulping down a sandwich and a piece of pie” was a thing of the past, one article declared. Considerable money was lavished on creating beautiful spaces for consumption. The furnishings of the lunch club incorporated into the New York Stock Exchange’s new 1903 building, for example, were changed from oak to mahogany at the cost of an additional $5,000 (or $142,000 in modern-day dollars). Butler took pride in the Lawyers Club being the “most sumptuous” of all the downtown clubs.[5]

View of Broad Street, undated (c. 1900–1919): Robert L. Bracklow Photograph Collection, New-York Historical Society. This view of Broad Street depicts (on the right hand side of the image) the entrances to a “quick lunch” establishment and the Exchange Buffet, the first self-service restaurant in New York City—the kinds of eating establishments that would have come to mind when the “rushing lunch-counter” was invoked.

Smoking room, Lawyers’ Club, 1902: Byron Collection, Museum of the City of New York. The lavishly-decorated smoking room of the Lawyers’ Club was one of several club rooms, besides the dining room, provided for members and their guests. The Byron Collection includes several other behind-the-scenes photographs of the Lawyers’ Club, as well.

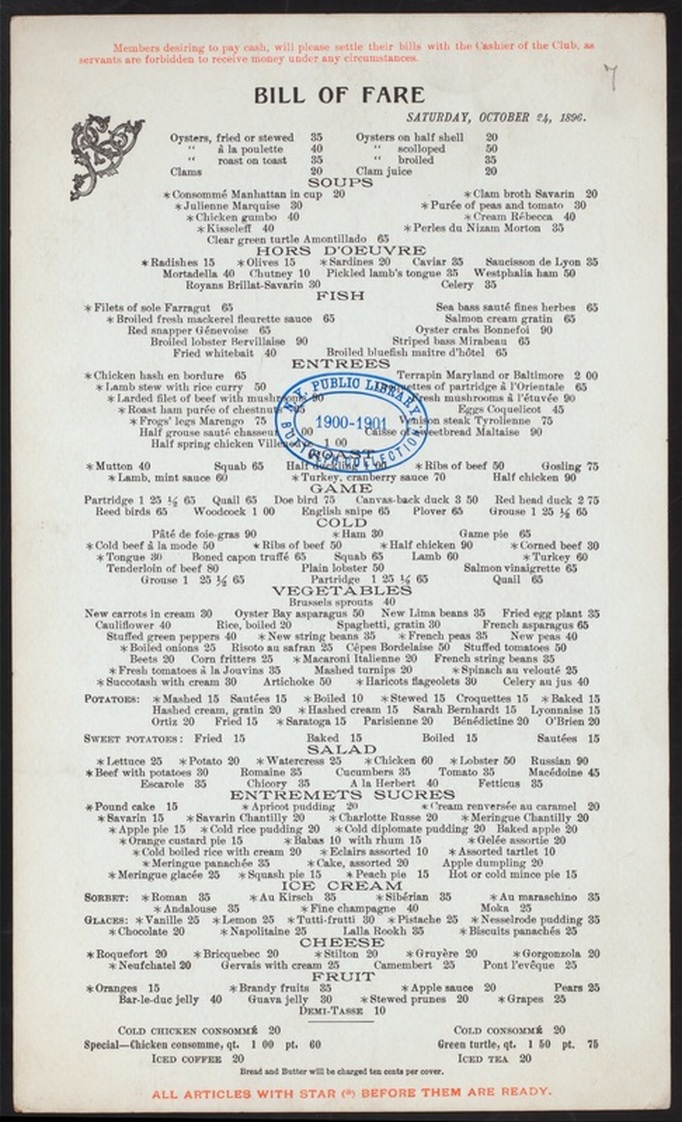

The dining experience in downtown lunch clubs was intended to invoke a feeling of sincere hospitality, rather than a hurried, commercialized encounter. Lunch club meals were “calmly, properly served,” and rules barred tipping waiters, enabling patrons to feel that the staff did not have to be “bribed” for good service. Instead of paying cash, bills were charged to a member’s account. In pursuit of high quality, the Lawyers Club hired a French chef, imported a special supply of Hungarian flour for its bread, and fired fifteen men, “one after another, for failure to make coffee properly.” A Lawyers Club menu from 1896 lists more than 300 items, ranging from succotash and ham to cold turtle consommé and broiled lobster.

Lawyers’ Club menu, 1896: What’s on the Menu collection, New York Public Library. The menu is listed in the NYPL collection as being from the Café Savarin, which was located in the same building as the Lawyers Club and shared the same kitchen. However, the menu can be identified as from the club rather than the restaurant by the intertwined “LC” initials in the corner and the reference to “members” paying their bills.

The club also offered a lengthy list of foreign and domestic wine and beers. The most expensive item, terrapin duck, was offered for $2.00. By comparison the weekly wage of a stenographer was roughly $5.00.[6] Still, descriptions of the clubs insisted that their luxuries were less important than their role in facilitating business. Men “may take time to eat” there, a journalist explained, “but it is not time wasted.”

One of the important factors in the clubs’ ability to be a place where men could do business was that, unlike the social clubs founded by Christians located uptown, the downtown lunch clubs did not discriminate against Jewish men. While Jacob Schiff and Otto Kahn of investment bank Kuhn, Loeb & Co. did not belong to the same uptown clubs as Robert Bacon and Charles Steele of J.P. Morgan & Co., all four men belonged to the Lawyers Club.[7] The clubs created “a new kind of sociability,” journalist Cleveland Moffett argued.

In many ways the lunch clubs were the harbinger of a shift from a culture in which business relationships were grounded on common family or religion background to a larger, more anonymous business network based on “weak ties.” This “new sociability” was based in part on the exclusion of women. As Maureen Montgomery notes in her study of gender and public life in the Gilded Age, “[w]omen did not belong, it seems, in public space.” Contemporary men commonly responded to the idea of mixed social clubs with “extraordinary antagonism,” arguing that the presence of women inhibited them from expressing themselves honestly and enjoying “good fellowship.” At most downtown lunch clubs, women usually visited only under strict conditions, typically as the guests of a family member.[8]

The reluctance to talk freely when women were around hints at the importance of the lunch clubs as spaces where men could exchange news, information, and rumors; in short, where they could gossip. The importance of gossip in creating local business communities has been under-examined, perhaps because of the persistent trope in American culture of gossip as something that only women do, or that men do only in trivial contexts. While it was popular to claim that gossip was “tiresome,” in fact its acquisition constituted an indispensable part of the professional’s day. Broker Eugene Meyer hired journalists to make contacts with bankers and other “outside business people” because he “didn’t like to go visiting and gossiping with people very much.” Lunch clubs were “stages” (to borrow Joanne Freeman’s term) for the semi-private exchange of gossip over a meal, “yet [were] public enough to avoid seeming secretive.” One of Meyer’s hires, a former Wall Street Journal writer, regularly reported on his “long talks” with various men, such as a lunch with mining entrepreneur Sol Guggenheim that yielded details about his company’s earnings well in advance of publication.[9]

By excluding women, men symbolically elevated the importance of what they talked about above the level of “mere” gossip. Indeed, besides the exchange of information, gossiping created a bond between men. In such exchanges, men often ostentatiously drew attention to their candor and implied a willingness to trust that their indiscretion would not be used against them. After revealing his plans to organize a new financial institution, for example, banker Thomas Lamont told a friend, advertising executive J. Walter Thompson, that the news was “only for your private eye” while simultaneously saying he could tell others “as you may deem it wise.”[10] Although it is impossible to reconstruct the conversations that occurred over the elegant meals at the city’s lunch clubs, likely many combined the sharing of information for private ears with the permission to share it as the listener deemed wise.

The relevance of the downtown lunch clubs ebbed over the following decades, due to the Great Depression, the growing importance of Midtown Manhattan as an alternative business district, and eventually the stigma they faced for discriminating against women. The region’s upper class fragmented as well, making membership in city clubs less important.[11] But the importance of gossip for exchanging information and building trust perhaps helps explains why gathering places in various business communities have persisted ever since, even though the era of the downtown lunch clubs has long passed.

The postwar business boom, too large to be contained in financial district clubs, helped spur the advent of the “three-martini lunches” depicted on Mad Men at Midtown restaurants, where deals were pitched and rumors traded back and forth. By the 1970s a growing celebrity culture encouraged a shift in which both breakfast and lunch were reimagined as opportunities for the elite to be on display, rather than dining behind closed doors. The Four Seasons and other establishments became the settings for “power lunches,” where maître d’s rather than membership committees regulated who was treated as insiders and who was relegated to a table in a metaphorical “Siberia.” Just as the downtown lunch club provided a stage for having private conversations in public, financier Peter G. Peterson described eating at the Four Seasons as “a social experience,” yet also as a place where the booths were “far enough apart that you can have a private discussion.” While the Four Seasons faces an uncertain future, the history of Silicon Valley restaurants like Buck’s of Woodside, where venture capitalists and startup entrepreneurs have held meetings that helped launch companies like Netscape and Paypal, points to the fact that even on the frontiers of the new economy the lunch table is still a good place to do business.[12]

Atiba Pertilla is a Research Associate at the German Historical Institute and a Doctoral Candidate at New York University.

[1] William Allen Butler, History of the Lawyers Club (New York, 1921), 11. (http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/

pt?id=coo1.ark:/13960/t8v98px5p;view=2up;seq=10). Background on the Butlers is given on pp. 5–8.

[2] On New York City’s elite social clubs, see David C. Hammack, Power and Society: Greater New York at the Turn of the Century (New York, 1982), 72–76 and Sven Beckert, The Monied Metropolis: New York City and the Consolidation of the American Bourgeoisie, 1850–1896 (New York, 2001), 58–59, 263–265. Noteworthy overviews on elite clubs in American society include E. Digby Baltzell, Philadelphia Gentlemen: The Making of an Urban Upper Class (Glencoe, Ill.: Free Press, 1958), chap. 13, and Diana Elizabeth Kendall, Members Only: Elite Clubs and the Process of Exclusion (Lanham, Md., 2008).

[3] Virginia Kurshan, “The Down Town Association Building,” designation report LP-1950, New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, 1997, 2 (http://www.nyc.gov/html/lpc/downloads/pdf/reports/downtownassoc.pdf); James A. Davis, Seventy-Five Years of the Merchants Club: Address, 3; “Merchants’ Club Fifty Years Old,” Greater New York: Bulletin of the Merchants’ Association of New York, Oct. 3, 1921, 10.

[4] Butler, History of the Lawyers Club, 18; Club Men of New York (New York, 1902); “Newest Luncheon Club,” New York Tribune, Oct. 13, 1901, part 2, 1.

[5] Kendall Banning, “Deals Across the Table,” System, Feb., 1909; Cleveland Moffett, “Mid-Air Dining Clubs,” Century Magazine, Sep., 1901, 644; “Building Committee” transcript, May 27, 1902, NYSE Building Committee Records, New York Stock Exchange Archives; Butler, History of the Lawyers Club, 20.

[6] Granthorpe Sudley, “Luncheon for a Million,” Munsey's, March, 1901, 843. Butler, History of the Lawyers Club, 17–18; Lawyers Club menu, call #1896–190, What’s on the Menu? project, New York Public Library. The menu is listed in the NYPL collection as being from the Café Savarin, which was located in the same building as the Lawyers Club and shared the same kitchen. However, the menu can be identified as from the club rather than the restaurant by the intertwined “LC” initials in the corner and the reference to “members” paying their bills. On the anxieties that tipping produced, see Andrew P. Haley, Turning the Tables: Restaurants and the Rise of the American Middle Class, 1880-1920 (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2011), 171–179.

[7] Sudley, “Luncheon for a Million,” 843; Club Men of New York, 1902 edn. For an incisive analysis of the social club memberships of Wall Street investment bankers, see Susie Pak, Gentlemen Bankers: The World of J.P. Morgan (Cambridge, Mass., 2013), 65–93. Sadatsuchi Uchida, the consul-general of Japan, is also listed as a member of the Lawyers Club, further indicating the club’s openness to men from a variety of backgrounds.

[8] Moffett, “Mid-Air Dining Clubs,” 646, 648; Mark S. Granovetter, “The Strength of Weak Ties,” American Journal of Sociology 78 (May 1973): 1360–1380; Maureen E. Montgomery, Displaying Women: Spectacles of Leisure in Edith Wharton’s New York (New York, 1998), 89, 95–96. One visitor to a public downtown restaurant, for example, drew the conclusion that a group of well-dressed women at another table were probably not “respectable” because “If they are respectable women, why are they eating away from their homes?” See “The Feeding of New York’s Down Town Women Workers,” New York Times, Oct. 15, 1905.

[9] S. A. Nelson, The Consolidated Stock Exchange of New York: Its History, Organization, Machinery and Methods (New York, 1907), 82 ("tiresome"); Eugene Meyer, “Reminiscences,” 99, Columbia University Oral History Project; G.W. Batson to Eugene Meyer, May 26, 1910, folder “Blumenthal, George W., #1,” box 216, Eugene Meyer Papers (Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.), and other letters in the same folder. Joanne Freeman’s study of a special kind of business community—the men who gathered to do the work of politics in 1790s Philadelphia—was very useful for developing my thinking about the importance of gossip in the close quarters of Wall Street. Joanne B. Freeman, Affairs of Honor: National Politics in the New Republic (New Haven, Conn., 2001), 52–78, esp. 52 (“stages”). For discussion of gender and gossip in the Gilded Age, see Amy Milne-Smith, London Clubland: A Cultural History of Gender and Class in Late Victorian Britain (New York, 2011), 87–107, esp. 89–91, and Molly Wood, “Diplomacy and Gossip: Information Gathering in the US Foreign Service, 1900–1940,” in When Private Talk Goes Public: Gossip in American History, ed. Kathleen Feeley and Jennifer Frost (New York, 2014).

[10] Toby Ditz, “Secret Selves, Credible Personas: The Problematics of Trust and Public Display in the Writing of Eighteenth-Century Philadelphia Merchants,” in Possible Pasts: Becoming Colonial in Early America, ed. Robert Blair St. George (Ithaca, N.Y., 2000), 219–242; Thomas W. Lamont to J. Walter Thompson, March 11, 1903, folder 133–21, box 133, Thomas W. Lamont Papers (Baker Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.).

[11] Clifton Hood, “Counting Who Counts: Method and Findings of a Statistical Analysis of Economic Elites in the New York Region, 1947,” Bulletin of the German Historical Institute 55 (Fall 2014): 57–68.

[12] William K. Zinsser, “There’s No Business Like Lunch Business,” The New York Times Magazine, March 20, 1960, 60, 62; Robert Draper, “You’ll Never Power Lunch in This Town Again,” GQ, Sep., 2015 (http://www.gq.com/story/power-lunch-four-seasons); Alex Kuczynski, “A Lunch Counter for the City’s Powerful,” New York Times, June 20, 1999. (http://www.nytimes.com/1999/06/20/style/a-lunch-counter-for-the-city-s-powerful.html). Eric S. Hintz, “Historic Silicon Valley Bar and Restaurant Review,” Bright Ideas blog, Sep. 9, 2013, Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation, National Museum of American History, http://invention.si.edu/historic-silicon-valley-bar-and-restaurant-review. On club membership in the postwar years, see Pamela Walker Laird, Pull: Networking and Success since Benjamin Franklin (Cambridge, Mass., 2006), 169–173, 303–310, and on the continued importance of private lunch clubs in other cities, particularly in Texas, Kendall, Members Only, 93–95.