“The presentation of the civic and commercial life of the city”: May King Van Rensselaer and the founding of the Museum of the City of New York

By Alena Buis

At the January 2, 1917 annual meeting of the New-York Historical Society (N-YHS), May King Van Rensselaer (1848-1925) delivered a passionate speech. Addressing the organization’s staid (and at that point startled) representatives she proclaimed:

I have been attending the meetings of the New-York Historical Society for nearly three years, and have not heard one new or advanced scientific thought, although many distinguished scholars have visited the city. Having been a life member of the society, I can no longer be silent on the conditions, which exist in an organization of which I should be proud but of which I am ashamed. I hear on all sides that the society is dead or moribund. Instead of being in the front rank of similar organizations in the United States, it is in the rear. Some members may be satisfied with present conditions; I am not. Many have told me they have resigned because of them. Only a few attend meetings because they are uninteresting and dull. And instead of an imposing edifice filled with treasures from old New York, what do we find? Only a deformed monstrosity filled with curiosities, ill arranged and badly assorted. And we ought to have another committee to rearrange the collections and enlarge them properly.[1]

May King Van Rensselaer - The Evening World. (New York, N.Y.), 01 Dec. 1920. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

The New York Times reported the next day that Van Rensselaer, “member of one of the oldest Knickerbocker families,” who with her “snow-white hair … looks like a Duchess of the Victorian period,” had “exploded a verbal bomb” on the “dignified company” of the twenty members and five guests present. Despite (or perhaps because of) their shock the motion was seconded by a man seated near Mrs. Van Rensselaer, “just to enable the matter to be discussed,” and finally “carried in a rush.”[2]

Although The New York Times reporter was shocked by Van Rensselaer’s behavior, Robert W.G. Vail, a later director of the N-YHS, indicated that Van Rensselaer made it a practice to be incendiary, calling her “the tempest in a teapot” and dubbing her attacks on the administration of the organization over several years prior to his tenure as “Mrs. Van Rensselaer’s War.”[3] In 1898 she had become a lifetime member of the N-YHS and from that point on became personally invested in the organization. She was even rumoured to have patrolled the premises “notebook in hand, looking for causes of dissatisfaction.”[4] From 1915 to 1920 she undertook a letter writing campaign, barraging then president John Abeel Weekes Jr. (1856-1939) with critical feedback on the running of the institution, threatening that if changes were not made she and her wealthy, well-connected friends would divert their patronage elsewhere. From these letters it is clear her main concerns were primarily the lack of a systematic acquisition strategy as well as significant doubts about the care of the objects already in the N-YHS holdings. Van Rensselaer thought these issues could be solved in part by establishing what she considered to be a democratic system of volunteer committees that could take on the responsibilities of managing and growing the institution’s permanent collection.[5]

Born in 1848 to Archibald Gracie King (1821-1897) and Elizabeth Denning King (1821-1900), Maria Denning King Van Rensselaer was indeed a member of the elite New York society tracing their roots back to colonial times. According to the society pages of The New York Times she was a “direct descendant of Mrs. William Alexander, born Polly Spratt, the most prominent female figure in the days of New Amsterdam.”[6] Her father was a descendent of Archibald Gracie, who left Scotland for America in 1784, where he became wealthy through investing in merchant ships. Her mother’s side had equally privileged connections, with her grandfather being William Alexander Duer (1780-1858), president of Columbia College from 1830 to 1842. This position was only furthered when she married John King Van Rensselaer, president of the Stirling Fire Insurance Company in 1871. Van Rensselaer was not only a wealthy businessman, but he was also a direct descendent of the Van Rensselaers, one of the first and most prominent Dutch families to settle the region. After her death, The New York Times lauded her position (“related by birth or marriage to most of the old ‘Knickerbocker’ families,”) and knowledge (“the repository of innumerable bits of family tradition throwing light on the social customs of the New Yorkers of the good old days of Dutch and English rule”).[7] Her obituary claimed that her “desire to bring the great facts of American history to the knowledge of present citizens of New York was made manifest” through her petitioning to reform the city’s cultural institutions.[8]

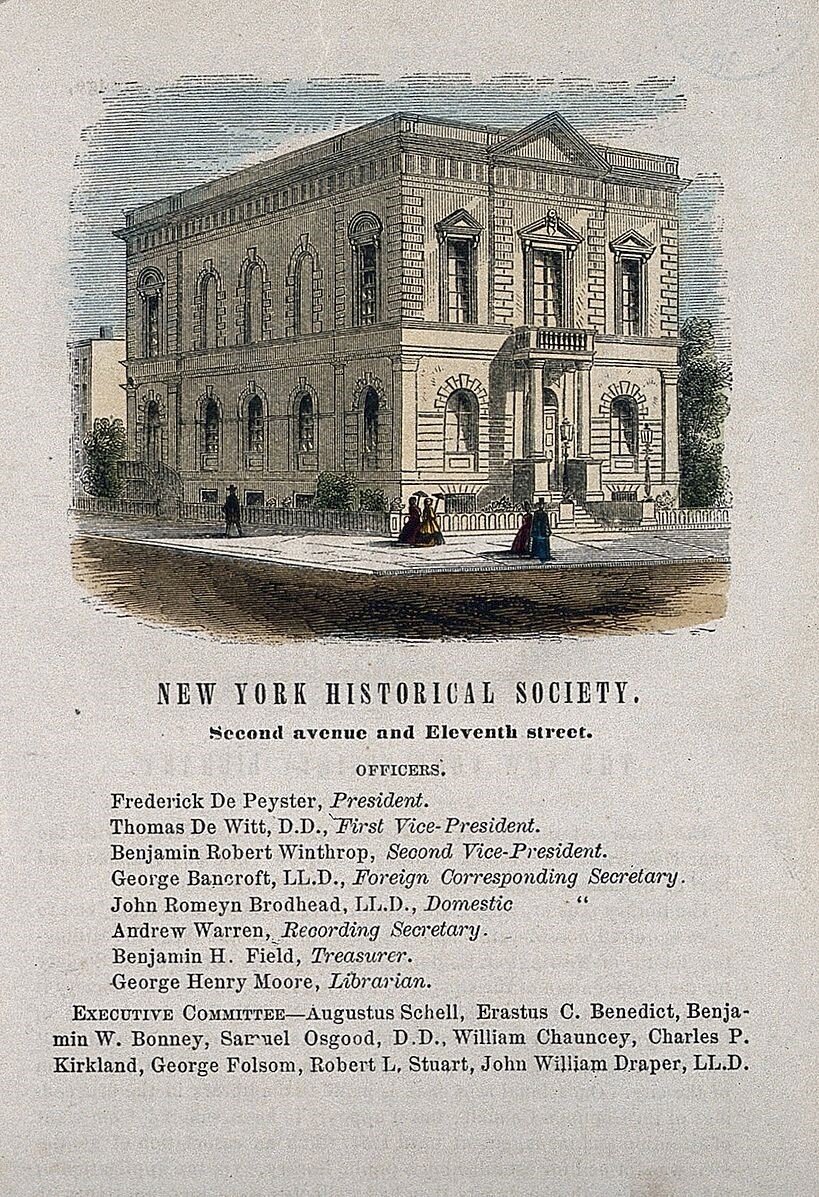

The New-York Historical Society, New York City, coloured wood engraving. Credit: New York Historical Society, New York City. Coloured wood engraving. Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Founded almost a century earlier, in 1804, with a mission to “discover, procure, and preserve whatever may relate to the natural, civil, literary, and ecclesiastical history of the United States in general, and this State in particular,”[9] the N-YHS was plagued by financial and organizational issues throughout its early history. During the 19th century its collections moved frequently, first to the Government House on Bowling Green in 1809 and then to the New York Institution, formerly the city alms-house, by City Hall Park. In 1857, the first building constructed specifically to house the collection was erected at the corner of Second Avenue and Eleventh Street. The N-YHS would remain there for the next fifty years until moving to its current location, Central Park West at West 77th Street. The imposing new Beaux-Arts style building was designed by the architects York and Sawyer, a firm well-known in North America for their neo-classical designs for banks, and hospitals. The first museum catalogue, printed in 1813, shows that the collection then included over 4,000 books, along with documents, almanacs, newspapers, maps, views and portraits. Many of these items had ties to the city’s early Dutch past. Over the course of the 19th century, the N-YHS collection of visual and material culture would rapidly and eclectically expand to include objects with little connection to the city’s history, for example ancient Nineveh sculptures, European Old Master paintings, and even Egyptian antiquities that would later be catalogued by Caroline Ransom Williams, now considered to be the first woman professionally trained as an Egyptologist. Even by early 20th-century standards the N-YHS was considered to be an out-dated hodgepodge of relics. One observer characterized the organization as dowdy: “Like an ancient spinster, who puts on her paint and her ornaments when she intends to ask a favour, the old Historical Society has sent up to its garrets and down to its cellars and bedecked itself with rare paintings...”[10]

In light of such a tarnished public image, changes were already in the works when Van Rensselaer voiced her concerns. Shortly thereafter, the N-YHS appointed a special committee of internal and external reviewers to examine its administration. The Third Vice President, the Treasurer and a member of the Executive Board were joined by Worthington C. Ford (1858-1941) of the Massachusetts Historical Society, John W. Jordan of the Pennsylvania Historical Society (1840-1921) and Clarence S. Brigham (1877-1963) of the American Antiquarian Society, who reported the Society’s faults were “sins of omission rather than commission… imperfections due chiefly to lack of means.”[11] Subsequent fundraising allowed for specialists to reorganize the collections, the paintings to be cleaned and properly labelled, newspapers bound, and books and manuscripts catalogued. In addition, it seems that Van Rensselaer’s criticism elicited a further response. Angered by her reproach, loyal members rallied to solicit substantial new donations, at least fifty new members joined, and the organization was restructured with the organizational by-laws revised.

Despite the changes at N-YHS, Van Rensselaer followed through on her threats and withdrew her support, taking other influential members of New York’s high society with her. On October 31, 1920 The New York Times reported that Van Rensselaer had held a meeting announcing her plans to open “a historical museum, under the patronage of twenty society women, representatives of the oldest families in New York.”[12] Several months later she announced their intentions: “We want a house of the year 1800, of which there are still half a dozen in the city. There we will install figures of men and women – call them wax figures, if you like – dressed in the costumes of their times and surrounded by the furniture they knew.”[13] Essentially what Van Rensselaer wanted to implement was a novel exhibition strategy. Foreshadowing later “living museums” she expressed a desire for a collection to come to life, for the things of their ancestors to be animated by displays showing how they would have been used and enjoyed. Under the auspices of the “Society of Patriotic New Yorkers,” a small collection of furniture and prints were shown inside her great-grandfather Archibald Gracie’s (1755-1829) mansion on the East River in 1923, under the curatorship of Henry Collins Brown (1862-1961).

Museum of the City of New York (2013)

Following these initial loan exhibitions, Van Rensselaer’s Society renovated Gracie Mansion and established the Museum of the City of New York (MCNY), directed by Brown. In 1925 Van Rensselaer passed away, but her vision to launch “an educational campaign to teach the inhabitants of the city and the state just what New York really is” [14] was achieved with the first museum devoted “to the presentation of the civic and commercial life of the city and the private life of the inhabitants.”[15] Over the next few years the MCNY “represented a distinctive addition to New York’s growing roster of history institutions,” for as Max Page notes it was the first American museum to focus solely on the material transformation of a city. By using relatively new techniques for museums — period rooms, dioramas, and models — it attempted to “create, out of a landscape subject to ‘constant restless reconstruction,’ a usable past.”[16] On January 4, 1932, now rapidly outgrowing Gracie Mansion, the museum reopened in its current location, a “commodious building” on Fifth Avenue between 103rd and 104th Streets. Along with old maps, prints, and “delightful models representing characteristic scenes [and] historical incidents” the museum also included regional products such as “the early New York silver [that] bears witness to the skill of the native craftsmen; costumes, pottery, pewter, and other handicrafts also help to visualize aspects of New York life and customs.”[17]

Van Rensselaer’s outspoken objection to the N-YHS’s collecting practices and her role in establishing new exhibition practices at the MCNY make her an important yet understudied forerunner of today’s institutional critique, the artistic and curatorial practice of critically questioning and reflecting on the structure of museums and galleries and how they shape on the concepts and social function of art and history. Her characterization of the institution’s dated approach to artifacts and even more problematic elitist exclusion of popular histories of the city echo much later objections to museums as places where things go to die. Theodor W. Adorno has commented on the “unpleasant overtones” of the German word museal (museumlike), for it “describes objects to which the observer no longer has a vital relationship and which are in the process of dying. They owe their preservation more to historical respect than to the needs of the present … the result is even more distressing than when the works are wrenched from their original surroundings and then brought together.”[18] Van Rensselaer clearly had similar concerns for the Society’s museal collections. In the days that followed a 1917 annual general meeting of the N-YHS, newspapers reported her performance with inflammatory headlines. The Tribune ran “Historical body is called dead” and the World declared “Mrs. Van Rensselaer shakes up dry bones.”[19]

Contemporary responses to Van Rensselaer’s concerns further speak to the gendered nature of museums and other institutions during the first quarter of the 20th century when they were either being expanded, as was the case with the N-YHS and the Metropolitan Museum of Art (especially the 1924 addition of the American Wing) or founded like the MCNY. The problem was not necessarily what Van Rensselaer was saying: the changes made by the Society clearly indicate they were striving to improve their collections management. The issue was that as a woman, however active in the upper echelons of society, Van Rensselaer was overstepping her bounds within the gendered (and raced and classed) roles clearly established at the time by voicing her critique. Enabled by her family’s wealth and social connections, she occupied a privileged position within the museum world, but one that was nonetheless complicated by the gendered character of American institutions. As much as she was a part of a well-documented social elite, she was also a part of a community of under-represented, volunteer women, whose collaborative, behind-the-scenes efforts have been marginalized in museum history. Their ability to influence museum policy was determined by their conformity to prescribed gender roles. Van Rensselaer’s efforts became problematic when her contributions challenged and ultimately disrupted contemporary gender norms. By claiming center stage for herself with a vocal critique of the Society, Van Rensselaer exceeded the private, quiet roles that women were expected to take in museum affairs. Her subsequent centrality in the founding of the MCNY has also been overlooked. May King van Rensselaer was an important figure in transforming the museum landscape of New York in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, yet her contemporaries and the museum historians that wrote the stories of these institutions in the mid-20th century marginalized her impact on the city’s cultural institutions.

Alena Buis, PhD is and Instructor and chair of the Art History and Religious Studies Department at snəw̓eyəɬ leləm̓-Langara College in Vancouver BC. She is also one of the founders of Open Art Histories (OAH) a SSHRC-funded collective, committed to building a generative and supportive network for teaching art history and addressing pressing pedagogical challenges, including globalizing the discipline and using OER/OEP to advance accessibility and inclusion.

[1] Quoted in New York Times (3 January 1917): 8.

[2] In contrast to this colourful account, the New-York Historical Society’s minutes blandly read as follows: “Mrs. Rensselaer with remarks submitted the following resolutions: ‘Whereas, It is desirable to appoint committees for entertainment, Be it Resolved, that there members be appointed by the President on each committee with power to act’ (sic).”

[3] R.W.G. Vail, Knickerbocker Birthday: A Sesqui-Centennial history of the New York Historical Society, 1804-1954 (New York: New York Historical Society, 1954), 205.

[4] Vail, Knickerbocker Birthday, 206.

[5] Letter of Mrs. Van Rensselaer to President Weekes (16 January 1915; 26 December 1916; 3 October 1917; 14 November 1917; 29 October 1917) New-York Historical Society Collections.

[6] “A Belle of Old New York,” New York Times (22 October 1898): BR710.

[7] “An Antiquarian of Society,” New York Times (13 May 1925): np.

[8] “Noted Authoress Dies at Home Here,” New York Times (12 May 1925): np.

[9] Quoted in Louise Mirrer, “Making History Matter: The New-York Historical Society’s Vision for the Twenty-First Century,” The Public Historian 33, no. 3 (Summer 2011): 90-98.

[10] Town Topics (6 November 1913): np.

[11] Report of the Special Committee of the New-York Historical Society unanimously approved and adopted at a stated meeting held February 6, 1917, New York: New-York Historical Society, 1917, 18.

[12] Vail, Knickerbocker Birthday, 213.

[13] New York Times (2 December 1920): np.

[14] Marion King, Books and People: Five Decades of New York’s Oldest Library (New York: McMillan, 1954), 161.

[15] John Shapley, “The New Museum of the City of New York,” Parnassus 1, no. 6 (October 1929): 32-34, 43.

[16] Max Page, “‘A Vanished City is Restored’: Inventing and Displaying the Past at the Museum of the City of New York,” Winterthur Portfolio 34 no. 1 (Spring 1999): 50.

[17] C. Louise Avery, “The Museum of the City of New York,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 27, no. 3 (March 1932): 61, 63-64.

[18] Theodor W. Adorno, Prisms, trans. Samuel and Shierry Weber (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1981), 175.

[19] Vail, Knickerbocker Birthday, 213.