The Remarkable Life of Teuntje Straetmans, a Woman in New Amsterdam

By Annette M. Cramer van den Bogaart

Today, when you look at the impressive facade of the neoclassical building at 55 Wall Street in Manhattan, known as the National City Bank Building, you would never guess that somewhere buried deep below its foundation lie the remnants of a house owned by a woman with a storied past in the Dutch Atlantic world. On a map of Manhattan in 1660, we find at the intersection of Wall Street and Williams Street the entry, “two small houses under one roof” listed as owned by “Teuntje Straetmans and her fourth husband.”[1]

Castello Plan from I.N. Phelps Stokes, The Iconography of Manhattan Island 1498-1909(v.2)(New York: Robert H. Dodd, 1915-1928), 324.

Following Straetmans winding journey from the Netherlands to New Amsterdam shows the many and varying paths that brought migrants to the city, and it highlights the resourcefulness and determination with which women, no less than men, approached settling there. Before she even arrived in New Amsterdam, Teuntje Straetmans had led a remarkable life for a 17th century woman. She migrated from the Netherlands to Dutch Brazil and then moved again, stopping in the Caribbean, before finally making New Amsterdam her home. Her life was different from the lives of her contemporaries who stayed in the Netherlands, but Straetmans’s life also differed from the lives of English women she met in the North American colonies. In New Amsterdam she lived in close proximity to the English and important distinctions can be made between the two cultures, particularly regarding female legal status and custom.

It has been well documented that foreign observers were surprised by the societal position and behavior of Dutch women. Generally calling Dutch women bossy and domineering, these observers also noted that Dutch women were surprisingly well-educated and proficient in reading, writing, and arithmetic.[2] The latter helped them keep account books and engage in trade. To the Dutch, marriage was a partnership in which husband and wife worked together to ensure the economic survival and prosperity of the family. Although legally women fell under the guardianship of their husbands, in practice, they often acted as agents for their families and engaged in trade and other businesses. Dutch women could also keep their property separate from that of their husbands through the use of prenuptial agreements, which were common.

Theodor Matham, Portrait of Johan Maurits of Nassau-Siegen, c. 1644. Available from: Encyclopaedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-Maurice-of-Nassau#/media/1/305028/15340

Teuntje Straetmans originally crossed the Atlantic with her first husband, Dutch West India Company (WIC) soldier Jan Meijerinck, when they sailed to Dutch Brazil in the mid-1630s. In this case, it is unlikely they had a prenuptial agreement. The couple were then probably living on his soldier’s wages and did not own any property, so there was little incentive to think about property divisions. In Brazil, the couple lived at the coastal fort Cabadelo, near present-day Recife, where Straetmans gave birth to a son named Mauritie. The child was likely named after the governor of Brazil, Count Maurits van Nassau [image], who, in a rare occasion, was present at the baptism in 1637.[3] Sadly, the couple lost their young son, but his death was followed by the birth of a daughter, Margariet in 1639.[4]

In the mid-1640s, tragedy struck. After ten years in Brazil, Straetmans’s husband died. It is likely that combat or disease caused his early demise for the Dutch casualty rate among men in Brazil was high. However, since there were many more European men than women in Dutch Brazil, it must have been fairly easy for Straetmans to find a new spouse. She married Georg Haff, a field-trumpeter who was employed by the WIC, and she gave birth to twin boys, Laurens and Pieter, who were baptized in 1649.[5] Yet again, she lost a child when Pieter died in infancy.

It is not clear exactly when Straetmans left Brazil or with whom. Most likely, she was swept up in the stream of refugees who left the colony during the early 1650s when it became clear that the Dutch would not be able to hold on to their possessions in Brazil. Around this time, Straetmans suffered the loss of her second husband and married yet again. Her third husband was Tieneman Jacobsen, with whom she had a daughter named Anna around 1654. At this point, records indicate that Straetmans was on the island of Guadeloupe with Jacobsen and her three children. When it came time to move on, however, Straetmans and her children left the Caribbean island, but Jacobsen remained behind. Straetmans chose New Netherland, likely because her sister, Barentie, was already there. It is unclear, however, why she left without her husband.

Straetmans arrived in New Amsterdam with a teenage daughter, a small boy, and an infant girl. Upon arrival she was, for all intent and purposes, a single woman. At first, she may have had some hope Jacobsen would join her, but eventually she had him declared dead, a necessary pre-condition for a new marriage. With the consent of director-general Peter Stuyvesant, she married Gabriel Corbesij, another Company soldier, in the Dutch Reformed Church in Manhattan on June 15, 1657. In the church records, the bride is described as a widow.[6]

During Straetmans’ marriage to Corbesij, we can see that, for the first time, she took advantage of Dutch property laws and arranged to keep some of her assets separate from those of her husband. The aforementioned houses at Wall Street were hers, purchased before she married. We find evidence of this in the Land Papers of New Amsterdam. In January of 1657, there is a mention of Straetmans in a patent (land grant) to Nicolaes Bernard. In the description of the location of his lot we find that it was “… 24 feet in length on the north side bordering Teuntie Straetmans,” which means she owned the homes prior to her wedding to Corbesij.[7] In July of 1660, the homes were still listed as hers in a patent given to another neighbor.[8] After she married Corbesij, Straetmans apparently held on to the property and rented the homes out for fifty guilders a year, while she and Corbesij moved to a small farm in Breuckelen (Brooklyn) at the Gowanus. Additional evidence of the fact that she kept her property separate from that of her husband is that the proceeds of the sale of the houses were listed in her inventory at the time of her death.

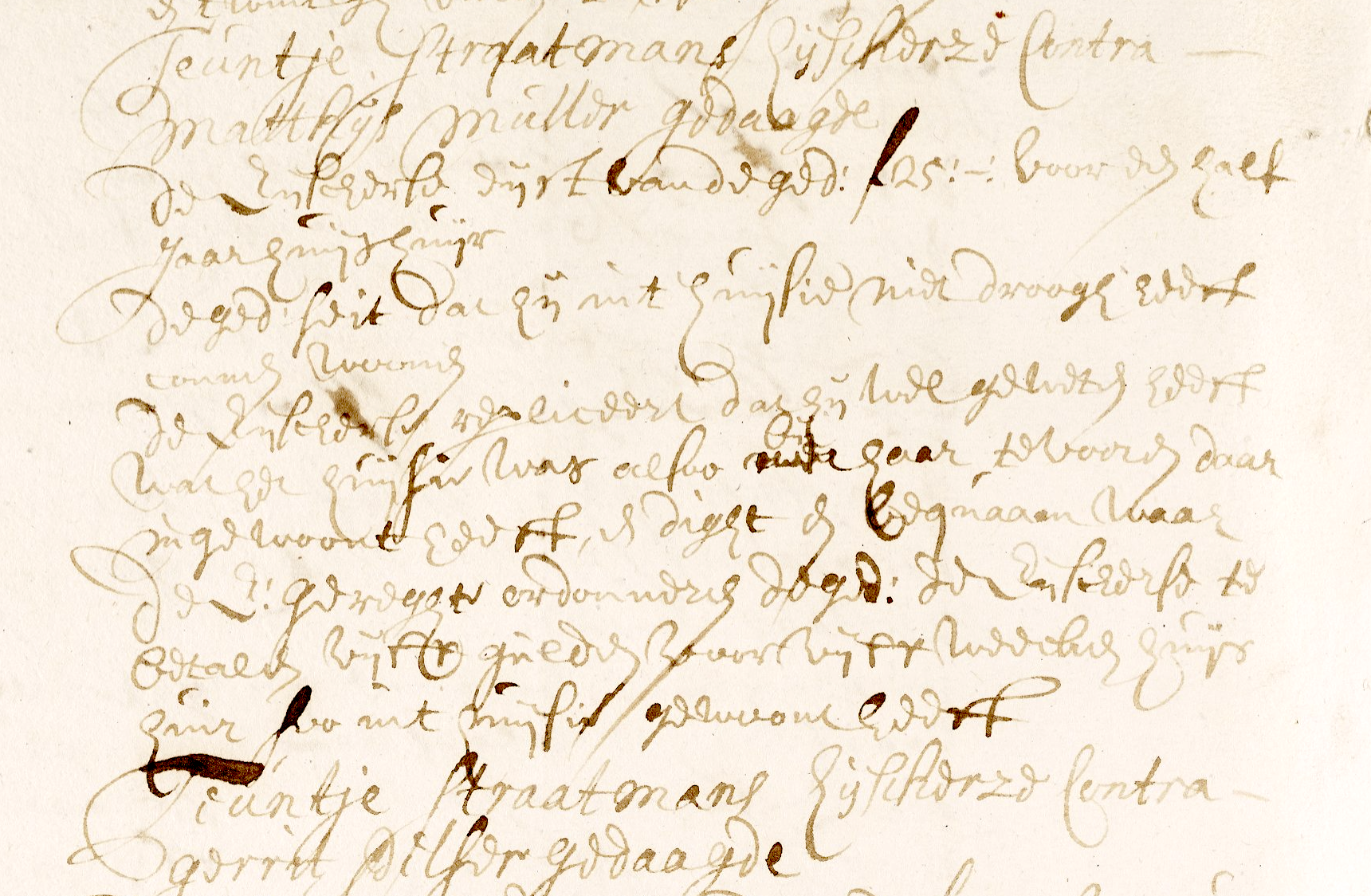

Minutes of the Court of Burgomasters and Schepens of New Amsterdam, February 24, 1660. New York City Municipal Archives. Available from https://newamsterdamstories.archives.nyc/nycma-records-new-amsterdam

A court case involving rent that was due on the property illustrates the fact that Dutch women, even when married, were considered competent to conduct business. In February of 1660, Corbesij appeared before the court of New Amsterdam demanding payment of 25 guilders in unpaid rent on the property at Wall Street. The tenant, Gerrit Pilsner, argued that while Straetmans had rented the house to him, she had also promised to fix leaks in the house. Because she had not done so, he had been forced to find other accommodations.[9] What is interesting to note here is that even though Corbesij was Straetmans’s husband and thus her legal guardian, the court refused to hear the case in Straetmans absence. Instead, Corbesij was told to have his wife appear in court. English women would not have been called to court to settle cases like this by themselves, and their husbands would have been judged competent to act in their stead. When the court met again, Straetmans did indeed appear as the plaintiff in two cases against the two tenants of her houses. She demanded payment from both, but because she had not kept the homes well, she received only a portion of the rent that was due.[10]

Also in 1660, Straetmans’ husband Gabriel Corbesij sued Lauwerens Caustersen, a soldier who owed him money. Yet Straetmans appeared in court on behalf of her husband. The court did not dismiss or postpone the case because the wife of the plaintiff came to represent him, and we know that this was not an isolated case. Women represented their husbands and families in multiple cases before the New Amsterdam court, though in this particular case, the court told Straetmans that it was not the proper venue for resolving the dispute.[11]

Further displaying her legal savvy, Straetmans also used New Amsterdam’s court to protect her reputation. The court system was open and accessible to ordinary citizens, and the famously litigious New Amsterdammers made good use of it. Because of the flexible procedures with simple rules of conduct, people did not need a law degree to plead their cases. Having a good reputation was important in the Dutch colony because in a small community one’s reputation was sometimes all one had. Historian Virginie Adane has pointed out that disputes over reputation in New Amsterdam had a gendered aspect to them as well, as accusations were commonly leveled against poor and middling women to ensure that they were reminded of their place in society. Their crude manners were juxtaposed to those of the more genteel, supposedly more moral, male authority of the upper classes.[12]

In a 1658 court appearance, Straetmans defended herself in a case brought by plaintiff Pieter Jansen. He accused Straetmans of insult and abuse involving name calling and a threat with a knife.[13] In 1660, Straetmans again had to defend herself in court. This time she was accused of having struck a woman named Styntie, “... so that the blood followed.”[14] Straetmans admitted the offense but claimed that Styntie had provoked her by publicly calling her a whore. When Straetmans could not deliver proof of the alleged provocation, she was convicted and fined.

The 1660 incidents were the last ones in the New Amsterdam records relating to Straetmans and her husband. She must have been in her mid-40s when on October 19, 1662, Teuntje Straetmans died. The minister of the Dutch Reformed Church of Brooklyn, dominee Henricus Selijns, and Teunis Jansen, deacon at the church, made the arrangements for her funeral. It was a simple service. Carel de Beauvois, the schoolmaster gave a “funeral oration” and she was buried in a plain wooden coffin.[15] Before her death, Straetmans had asked Selijns and Jansen to be the executors of her estate, so after the funeral they went to her house at the Gowanus to take an inventory of her possessions. Most likely they also discussed with Corbesij and Margriet Meijerink, Straetmans oldest daughter who was married by this time, what to do with the two youngest children, Laurens and Anna, eleven and eight years old respectively.

According to Dutch law, a child became an orphan if either one or both parents died, and in this case, the surviving spouse was not even the biological father of the children. Ordinarily, the Orphanmasters would take care of the orphaned, but since Straetmans had asked her minister to take care of her children, the church took charge of her affairs. Selijns made sure the children were cared for by two different families. Laurens was placed with Selijns for a contract period of six years, while eight-year-old Anna was placed with the family of farmer Gerrit Cornelissen who lived at a farm in Midwout (Flatbush).

Selijns also had to make sure the children received their “just due” from their mother’s estate. Dutch Parents were concerned with the well-being of both male and female offspring, and both inherited from their parents. Straetmans estate was divided according to Dutch custom, which dictated that property was divided into two equal shares: one part went to the surviving spouse, while the other part was divided equally among the children regardless of their gender.[16] In the inventory of Straetmans’s belongings, there are some illustrations of this division of property. For example, she left two pieces of linen measuring 35 els (24 meters). Selijns writes, “which was divided in two: one half for Gabriel Corbesij and the other half for the children; [this latter half] will be subdivided in three: for Margariet, Laurens, and Anna.”[17] After the English takeover in 1664 a slow transition in inheritance practices took place, and sons came to be favored over daughters, as was the custom among the English.

Just when the children’s lives must have regained some sense of normalcy, the church leadership received shocking news. On February 17, 1664, a traveling Englishman informed Selijns that Tieleman Jacobsen, Straetmans’s third husband, was actually still alive on the island of Jamaica. The church leadership decided to write a letter to Jacobsen to inform him of his wife’s death, and they assured him that his daughter Anna was with a family who treated her very well and “like your daughter as much as their own children.” [18] The church then added that he might want to send for his daughter or send her something as a “token of paternal affection.”[19] Not wanting to hand over Anna to just anyone, Selijns suggested Jacobsen could get a warrant with “proper procuration and a certain statement” from his governor or a magistrate so that they would know for sure he is alive and well and whether he wanted Anna sent to him, the “risen father.”[20] From Selijns’ correspondence it becomes clear that Jacobsen had wanted to go to New Netherland but changed course once he learned that his wife had remarried. Bigamy was a serious crime and Jacobsen’s appearance would have led to, at the very least, an uncomfortable situation. But after Straetmans’s death, it seems that Jacobsen did indeed settle in New Netherland to care for his daughter.

From Straetmans’s story, it becomes clear that some women, like men, were highly mobile migrants in the Atlantic World. She was one of the many women who lost several husbands, and without a spouse, she had to fend for herself and her children in foreign, sometimes even hostile, lands. When Straetmans arrived in New Amsterdam, she was clearly able to take care of herself, purchasing two small houses before marrying her fourth husband. Moreover, she was able to hold on to this property and preserve it for her children. During her final years, the English were slowly encroaching onto territory the Dutch considered theirs. In 1664, the English took over the colony and with the introduction of their common law system, many rights of women slowly eroded.

Annette M. Cramer van den Bogaart received her Ph.D. in History from Stony Brook University and is currently an adjunct assistant professor at Farmingdale State College (SUNY).

[1] I.N. Phelps Stokes, The Iconography of Manhattan Island 1498-1909 (v.2) (New York: Robert H. Dodd, 1915-1928), 324. The houses owned by Straetmans are listed at block Q: nr. 1 on the Castello Plan of Manhattan, created by surveyor Jacques Cortelyou in 1660. Under the direction of Toya Dubin and Nitin Gadia, the project “Mapping Early New York” is underway at the New Amsterdam History Center in order to create “New Amsterdam at Any Time” using Google Maps. (New Amsterdam History Center Newsletter, Vol. 3, no. 1, Spring 2020.) A beta version of an overlay of the modern map of Manhattan and the Castello Plan is available at https://www.thenittygritty.org/nahc/encyclopedia/map/swipe.html.

[2] See among others: Els Kloek, Vrouw des Huizes: Een cultuurgeschiedenis van de Hollandse huisvrouw (Amsterdam: Balans, 2009), 81-86. Kim Todt, “’Women are as Knowing Therein as the Men’: Dutch Women in Early America” in Women in Early America Thomas A. Foster, ed. (New York: New York University Press, 2015).

[3] C.J. Wasch, Doopregister der Hollanders in Brazilië, 1633-1654 (‘s-Gravenhage: Genealogisch en Heraldisch Archief, 1889). Mauritie was baptized on November 1, 1637.

[4] Ibid, Margariet was baptized “Margarita” on April 20, 1639.

[5] Ibid, June 30, 1649

[6] Records of the Reformed Dutch Church in New Amsterdam - Marriages (New York Genealogical and biographical Record, 1890 and 1940).

[7] Charles T. Gehring, trans. & ed. New York Historical Manuscripts: Dutch, Volumes GG, HH & II, Land Papers. (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc., 1980), Patent HH72.

[8] Ibid., Patent HH113, July 13, 1660.

[9] Minutes of the Court of Burgomasters and Schepens of New Amsterdam, February 17, 1660. New York City Municipal Archives. Available from https://newamsterdamstories.archives.nyc/nycma-records-new-amsterdam

[10] Ibid., February 24, 1660.

[11] Ibid., June 8, 1660

[12] Virginie Adane, “Trading Places: Men, Women and the Negotiation of Gendered Roles in the Port of New Amsterdam, 1630-1664,” De Halve Maen, 86, no. 3 (Fall 2013), 51-58.

[13] Minutes of the Court of Burgomasters and Schepens, August 27, 1658.

[14] Ibid., September 14, 1660.

[15] A.P.G. Jos van der Linde, trans. & ed. Old First Dutch Reformed Church of Brooklyn, New York: First Book of Records, 1660-1752 (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc., 1983), 77.

[16] Narrett, chapter 4.

[17] Van der Linde, ed., 51.

[18] Ibid., 81.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.