“The Scourge of the ‘90s:” Squeegee Men and Broken Windows Policing

By Jess Bird

There is perhaps no other bogeyman of New York City’s “bad old days” that has incited greater ire than the squeegee man. Cars created a sense of safety, of separation from the unruly world of the street, but a window washer approaching a car stopped at a red light ruptured that sense of safety, incited panic, and demonstrated, to some, a breakdown in law and order. Squeegee men, “the scourge of the ‘90s,” symbolized the need to be tough on crime, regardless of the costs.[1] Unsurprisingly then, the so-called squeegee pest featured heavily in the mayoral race of 1993, a rematch between incumbent Mayor David Dinkins and Rudy Giuliani. Squeegee men encapsulated Giuliani’s belief that toleration of this petty street disorder invited more serious crime. He was not alone in this belief. Broken windows theory, popularized in a 1982 Atlantic article by George Kelling and James Wilson, held that small acts of disorder — graffiti, public intoxication, or the proverbial broken window — invited more serious crime. Not addressing the smaller issues, Kelling and Wilson argued, indicated to criminals that their actions would go unpunished. The theory has mostly been discredited, but in the early ’90s, many New Yorkers embraced the idea that high crime rates justified encroaching on peoples’ rights. Squeegee men, though small in number, were highly visible, thanks in part to media attention. They served as an easy initial target of zero tolerance policing and their successful removal underwrote the turn toward removing sex workers, the street homeless, and vendors from public spaces in addition to the overpolicing of Black and brown communities through stop and frisk.

Giuliani successfully campaigned on the idea that the city was “out of control under an administration that [was] out of touch.”[2] If squeegee men symbolized the city’s decline, then Giuliani positioned himself as the former prosecutor tough enough to take them on, promising a “police crackdown with assault charges against [windshield washers] who ‘menace’ and ‘extort’ drivers.”[3] The Mayor-elect made little secret of his aim to reclaim the city’s streets. “We need to change the city. We need to get control of it,” he said. “The streets are overwhelmed with drug dealers,” he told supporters. “We can’t allow people to walk the streets and be threatened. Those people need to be removed from the streets.”[4] While Giuliani would eventually set his sights on clearing sex workers and adult businesses out of Times Square and curtailing street vending, squeegee men proved an easy first target. They were smaller in number than vendors, existing laws rendered their removal from the street easier than rezoning businesses, and it would play well politically with constituents from the outer boroughs who drove into the city and were therefore more likely to encounter squeegee men at major exits, entrances, and off ramps.

One observer of Giuliani noted that he truly believed his vision for the city was in everyone’s best interest. “He views privacy and the rights of innocent citizens as a far lower value than law enforcement’s domination of not only the streets, but also private areas of people’s lives.”[5] This was a summary not just of Giuliani’s totalitarian vision, but of a broader reframing of what a civilized society entailed. In order to protect the interests of the larger community, the individual rights of some New Yorkers would have to be curtailed.[6] What better way to enact that vision than by removing squeegee men from the streets of New York City?

Giuliani had the benefit of a recently commissioned report on the perceived benefits of managing squeegee men. George Kelling, one of the originators of broken windows theory, had been commissioned by Mayor Dinkins and his police commissioner Ray Kelly to study the squeegee “problem.” Sampling fewer than 50 drivers and squeegee men in “an attempt to shape police policy and practice with… available data and data that can be easily and inexpensively gathered and analyzed,” the report’s methodology was flawed. Kelling and his co-authors nonetheless found the results persuasive as they were “consistent with our earlier intuitions and beliefs.”[7] Those intuitions and beliefs were that squeegee men demonstrated the need for zero tolerance policing due to their repeat offenses; that police were the only city agency capable of stopping the squeegee “menace;” and that New Yorkers wanted the police to do something about the problem.

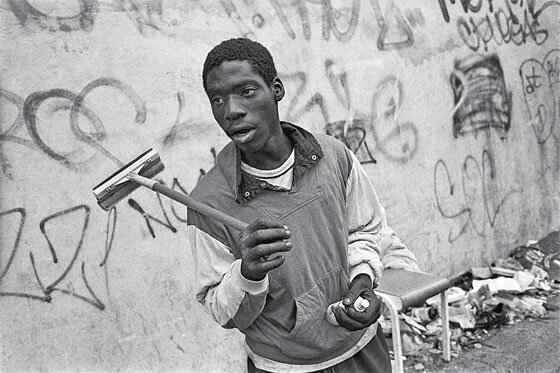

Squeegee man on the Cross Bronx Expressway. Photo: Edward Keating/Contact Press Images

Kelling and his team observed and videotaped window washers, had officers drive unmarked cars as decoys, and interviewed squeegee men, officers, and eighteen drivers. They divided squeegee men into three categories: two sets of competent, hardworking window washers and a third group of “fairly pathetic hangers-on [who appeared] burnt-out and seriously under the influence of alcohol, drugs, or both.”[8] The latter group, they observed, typically worked alone. The hardworking washers constituted the majority of window-washers. Kelling split them into a good-natured group who would retreat if waved off and a more aggressive group who appeared “to behave in ways that are calculated to menace drivers.” This piece was key — the quality of the job done by squeegee men ultimately did not matter, it was the manner in which they performed that counted. The report only mentioned two instances of observed aggression over several days of surveillance. One involved the squeegee men draping themselves on the hood of the car to prevent its movement and the other involved an argument between a window washer with a pipe and a driver who ultimately sped away. However, the larger aim of “Managing Squeegeeing” was to demonstrate that the NYPD could effectively address quality of life problems. These problems — “panhandling, drunkenness, public urination, boisterous youth, etc” — represented threats to the social order, creating fear and potentially “interrupting important urban activities.”[9]

For the study, Kelling had relied on a Department of Transportation rule issued in April 1992 that banned people from washing windshields and selling flowers, newspapers, or other items to drivers stopped at red lights. The rule gave police the power to arrest and charge individuals with misdemeanors, but at the time a DOT spokesperson said they were more likely to simply ask them to move along. After all, “it would be an extraordinarily difficult thing to enforce, because obviously there are more important things to enforce.”[10] After taking office, Giuliani and his new police commissioner would decide there were not more important things to enforce. However, immediately following Giuliani’s victory, squeegee men working the 56th street exit of the West Side Highway told a reporter they were unconcerned about the new mayor. Come better weather in the spring, they would return. “I mean, what else are we supposed to do?” asked one of the men interviewed. When the reporter pressed them on being targets of incoming police commissioner Bill Bratton, another responded, “you think stone killers uptown going to say, ‘Check out what the cops are doing to those raggedy squeegee guys – we better get out of town real quick?’”[11] Windshield washers understood the flawed logic of broken windows policing; arresting them was not going to prevent robberies elsewhere in the city, but that did not mean it would not be implemented and touted as critical to New York’s crime reduction in the coming years. What mattered most were the optics for those who supported Giuliani and his policies. Whereas prior administrations had let the city slip into decline, Giuliani visibly took action, empowering the police to restore law and order.

Restoring for whom and in what way may have gone unsaid, but growing concern over the militarization of the NYPD revealed the racist underpinnings of law and order rhetoric. A 1994 NYPD memo, “Police Strategy No. 5: Reclaiming the Public Spaces of New York,” outlined the new zero tolerance policy. Police were tasked with arresting people for everything ranging from reckless biking to loud music. “Much of this antisocial behavior is illegal, but for many years police managers have not taken aggressive action to restore order to public places,” the memo noted.[12] Misdemeanor arrests rose by fifty percent, and while some supported the new tactics, others questioned the literal and figurative price. Zero tolerance policing led to an increased abuse of power. Between 1994 – 1996, the city received 8,316 complaints of police misconduct, up from 5,983 for the period between 1991– 1994. In addition to the trauma inflicted upon Black and brown communities, reclaiming the city’s public spaces cost the public — in overtime and settlements. In the same periods that complaints rose, the city spent $70 million to settle police misconduct cases, up from $48 million in the prior years.[13]

The image of the squeegee man is what made the crackdown politically useful. In “Managing Squeegeeing,” Kelling conceded that, “the likelihood of having one’s windows washed at any particular intersection is slight.”[14] There were never that many squeegee men, nor were average New Yorkers likely to encounter them. In fact, the report estimated that fewer than 100 people consistently worked as window washers in the city. Kelly and Kelling selected squeegee men for their “problem-solving exercise” because “virtually no one [had] supported continued toleration of ‘squeegee men.’” Whether or not the so-called squeegee menace ever represented a serious problem, their image combined fears of the homeless, drug users, and young men of color.

A fateful encounter between a police officer and a squeegee man in the late 1990s highlighted the NYPD’s ability to defend itself by playing on popular antipathy toward squeegee men. In the summer of 1998, Antoine Reid was working an exit of the Major Deegan Expressway in the Bronx near Yankee Stadium. According to witnesses, Reid soaped up the windshield of an off-duty police officer named Michael Meyer, who became agitated and argued with Reid. The squeegee man offered to wipe the soap off, at which point Meyer exited his vehicle, pulled out his service weapon and pressed it to Reid’s chest, and fired. The bullet passed through Reid’s chest and struck the car behind him. Meyer then allegedly picked up Reid’s squeegee, turning to bystanders and saying, “See, everybody? He tried to rob me.”[15]

New York Post cover from 2014. Squeegee men continue to be invoked as signs of decline. Photo: Robert Kalfus.

Miraculously Reid survived, albeit without a spleen and with permanent damage to his liver. Meyer was charged with second-degree attempted murder, assault, criminal possession of a weapon, and reckless endangerment.[16] During his trial, the defense portrayed Meyer, who had previous complaints for excessive force, as a hero and Reid as a violent criminal, dredging up an earlier arrest in which he had been charged with armed robbery with his squeegee listed as a weapon. In their retelling, Meyer acted in self-defense when Reid attempted to rob him. Meyer testified that he feared “this guy was going to do some serious damage to me, that he was going to kill me. We were involved in a violent struggle.”[17] However, all the witnesses to the shooting noted that Reid was backing away as Meyer approached him with his gun drawn. The defense continued to make its case based on the idea that squeegee men were a public menace, bringing an alleged former victim of Reid’s to testify that he had been threatened by the window washer and so scared he ran a red light. When the prosecution asked whether said squeegee man was in court, he pointed to Reid’s brother sitting three rows back.[18] Meyer was ultimately acquitted, with the judge ruling that the prosecution had not disproven that Meyer acted in self-defense.

Reid’s shooting and Meyer’s acquittal was a predictable conclusion to state-sponsored violence. Broken windows theory and quality of life policing further criminalized Black and brown New Yorkers in a process that had begun in the early-20th century.[19] By focusing on the policing and punishing of squeegee men, Rudy Giuliani was able to present himself as a take-charge defender of public roadways and New York drivers’ personal space. Although they have become comparatively rare, squeegee men maintain a hold on the public consciousness and are invoked periodically to suggest that the city is in decline. At present, as the city faces rising unemployment and budget cuts, a new wave of struggles over space, safety, policing, and what constitutes a nuisance is emerging. How New Yorkers respond will be a reflection of our values as a community. In the early 1990s, a small group of hustlers were used to justify expanded police powers on the basis of fear. In addition to paying attention to budget priorities we also need to reflect on who it is New Yorkers are encouraged to fear and why.

Jess Bird is currently a Mellon/ACLS Public Fellow. Her work explores regulation of the informal economy in late 20th-century New York City.

[1] Sam Raskin and Jorge Fitz-Gibbon, “Squeegee men, scourge of the ‘90s, are back in New York,” New York Post, February 16, 2020.

[2] Catherine Mangeold, “Fight Vowed by Giuliani On Narcotics,” New York Times, September 10, 1993.

[3] Francis Clines, “Candidates Attack the Squeegee Men,” New York Times, September 26, 1993.

[4] Catherine Manegold, “Giuliani, On Stump, Hits Hard at Crime and How to Fight It,” New York Times, October 13, 1993.

[5] Bob Herbert, “Pushing People Around,” New York Times, February 25, 1999.

[6] George Kelling, Michael Julian, and Steven Miller, “Managing Squeegeeing: A Problem-Solving Exercise,” February 1994, New York City Hall Library. “most citizens have no difficulty balancing civility, which implies self-imposed restraint and obligation, and freedom. According to the authors, a small group of citizens did not “balance their freedoms with obligations” and believed they were “free to do and say what they [liked].” Those who failed to balance freedom with obligation ranged from murderers and rapists to “boisterous youth,” who through their actions threatened the social order “by creating fear and criminogenic conditions.” The authors of the report sought to bridge society’s ambiguity to “disorder” with “public demand for restoration of order.” Their suggestions were to curtail the rights of some for the greater good.

[7] Kelling and his co-authors also conceded that their sample size “did not meet scientific standards of representativeness.” From “Managing Squeegeeing.”

[8] Kelling et al, “Managing Squeegeeing,” 1994.

[9] Kelling et al, “Managing Squeegeeing”

[10] Steven Lee Myers, “New York to Ban Street Windshield Washers,” New York Times, January 12, 1992.

[11] Michael Kaufman, “Their End? Squeegee Guys Say No,” New York Times, December 8, 1993.

[12] Matthew Purdy, “In New York, the Handcuffs Are One Size-Fits-All,” New York Times, August 24, 1997.

[13] Ibid.

[14] “Managing Squeegeeing,” 1994.

[15] Michael Cooper, “Squeegee Man Gives Account of Shooting by Police Officer,” New York Times, June 19, 1998.

[16] Michael Cooper, “Officer in Squeegee Man Shooting Has a Civilian Complaint Record,” New York Times, June 16, 1998

[17] Kit Roane, “Squeegee Man Scared Him, Officer Says,” New York Times, June 25, 1999.

[18] Kit Roane, “Officer’s Intent Debated at Shooting Trial,” New York Times, June 26, 1999.

[19] Khalil Gibran Muhammad, The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2010).