The Show that Saved the Amphitheatre

By Daniela Sheinin

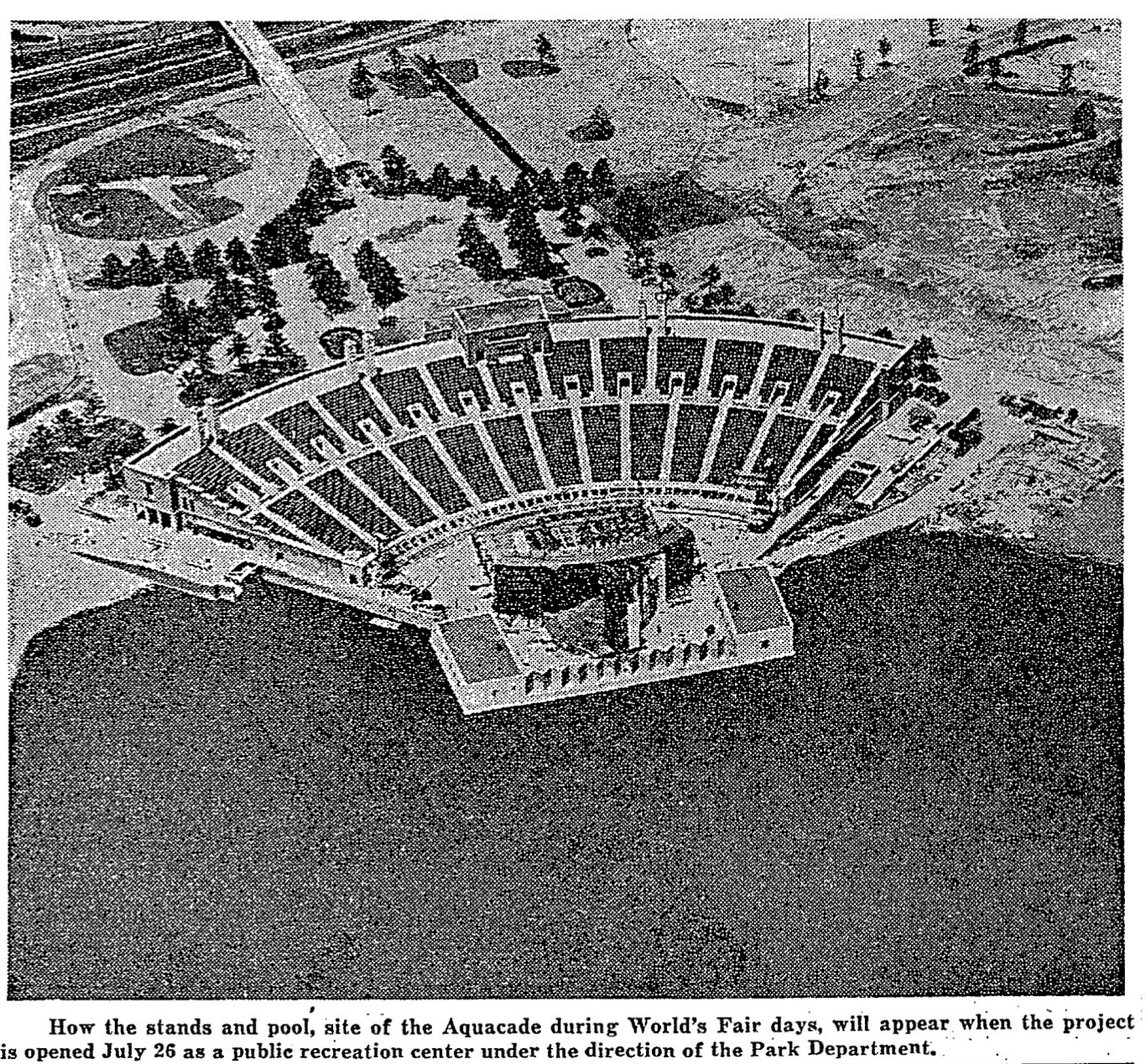

The amphitheatre from above

New York Times, July 14, 1941

On a summer evening in June 1945, 200 performers took to the aquatic stage at the former New York State Pavilion at Flushing Meadow Park. Spread throughout the 8,500 seats at the northern tip of Meadow Lake, spectators watched swimmers and a choreographed “water ballet” fill the pool, while divers sprung from the diving towers at each end. A lively band accompanied the water acts for the three-hour performance. The partially-submerged spectacle was a special preview for a new seasonal show, “The Water Follies of 1945.” Originally built for the 1939 New York World’s Fair, the amphitheatre would host its first event since the fair closed four and half years ago.[1]

The Water Follies were the brainchild of Elliott Murphy, the unpredictably eccentric showrunner and former comedic diver at Jones Beach. In the decade following his 1945 debut at the former New York State Pavilion, Murphy dazzled audiences with vaudeville thrills, water dances and comedic routines, orchestra-accompanied synchronized swimmers, and more. Murphy's extravaganza enticed tens of thousands of spectators and attracted national press, but not without making enemies. Murphy, with his unconventional performances, advertising, and tendency to circumvent any and all regulations, was a constant source of aggravation to authorities — especially Parks Commissioner, Robert Moses and his colleagues at the NYC Department of Parks. Renamed Elliott Murphy’s Aquashow, the amphitheatre’s most successful attraction after the World’s Fair ran with increasing sensationalism each summer until its end 12 years later.

While Parks officials remained concerned that vaudeville-style entertainment might lessen the splendor of the space, those acts brought in the money the Parks Department desperately needed. Even as they sent letter after letter reprimanding Murphy for his rash decisions, Murphy forged ahead, each season bolstered by the preceding year’s ticket sales. Elliott Murphy’s Aquashow offers a case study of how the park served as a stage for conflicting notions of Queens more broadly. Robert Moses and others saw Queens as an outpost for Manhattan sophistication and high culture. Many in Queens saw themselves as part of something new: suburbanites with a penchant for commercial entertainments, a new social and cultural order. While the Parks Department had greater ambitions for the amphitheatre’s post-World’s Fair life, Murphy’s Aquashow soon proved indispensable; he had the audience on his side. The fraught relationship between the Aquashow and the Department of Parks reveals a great deal about conflicting visions for the postwar development of Queens.

With the closing of the World's Fair in October 1940, the New York City Department of Parks assumed ownership of the fairgrounds and began transforming it into what would become Flushing Meadow Park (today’s Flushing Meadows – Corona Park). The amphitheatre was one of the few Fair structures designed as a permanent fixture and planners quickly set out to repurpose it. Available state and municipal funding hinged on the project’s utility to neighborhood growth and wellbeing, so the decision was made to convert the facility into a community pool as part of the Flushing Meadow Park plan.

Still, funding challenges remained a priority. Even as the Parks Department added locker rooms and comfort stations to accommodate local swimmers, officials sought alternative uses for the space. Realizing that a neighborhood pool would likely generate insufficient funds to pay for its own maintenance, the Parks Department signaled in early press updates that the venue could also easily accommodate large audiences for concerts and other performances. Hoping to transport highbrow Manhattan entertainment into Queens, the Parks Department inaugurated these efforts by scheduling a performance of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra for the amphitheater's opening ceremonies in July 1941. This, officials imagined, would mark Flushing Meadow as a premier New York City performance space, while at the same time advertising their achievement in developing new neighborhood facilities.[2]

Nevertheless, officials shared an uneasiness about the site’s sustained ability to generate revenue. If they limited performances to the symphony orchestra, would Queens residents show up? Could they count on Manhattanites trekking to Flushing Meadow for every show? To curb their anxieties, they considered additional features to cultivate a “light, merry mood” that would still reflect the dignity of the Philharmonic. Aware that “light stuff” would draw a larger crowd than “heavy, dull” classical composers, Parks officials planned to include a five-minute water ballet routine as the first half of the show ended. During the intermission, they would have five minutes of professional diving, followed by five minutes of “clown diving.” Nothing too crazy, just a light touch of humor.[3]

It was not enough. It took considerable persuasion for the Philharmonic chairman to agree to deviations from the traditional program, and, according to one audience member, it looked like they had still failed to fill the stadium seats by half.[4] They experienced technical difficulties with the stage speakers, dissuading other symphony representatives in the audience from renting the space. They couldn’t please anyone. They ultimately failed to secure a lasting relationship with the Philharmonic, and anticipating a vacancy in the 1942 season, they searched for another act.

As Robert Moses pondered the options, the Jones Beach Magic Water Ballet caught his attention. The popular show on Long Island’s southern shore featured “rhythmical swimming,” water skiing, an aquaplaning troupe, “fancy” diving and “the hilarious Jones Beach water clowns.” This was the key to success, he and his colleagues decided. It wasn’t the Philharmonic, but it would do in a pinch.[5]

Enter Elliott Murphy, the former Jones Beach lifeguard and diver. What began as a modest show quickly transitioned into an aquatic spectacle showcasing experienced and sometimes quite famous singers, dancers, divers, musicians, and swimmers. Shows featured a series of often wacky delights, from synchronized swimmers and divers, to clowns and animal acts. The show included diving clowns who would “sleepwalk off a high platform, ride wheels and rubber horses off high diving boards, stumble nose dive, bull-frog, pan-cake, and cascade in pyramids of four and six into the water.”[6] By 1949, the amphitheatre held a 200-foot stage with a 78-foot rotating platform. The show had featured headliners like “veteran vaudevillians … Buck and Bubbles” and Milt Britton with his “‘crazy’ orchestra.” By that season, in just 10 weeks almost half a million visitors attended, pushing gross revenue over $400,000.[7]

The Aquadorabelles perform the water ballet

New York Times, July 31, 1955

A novelty animal act for the 1954 season

New York Times, June 23, 1954

As Murphy continued to draw record numbers, the Department of Parks proved unsuccessful at reining him in. Officials begrudgingly maintained a contentious relationship through the years as Murphy felt more emboldened as each successful season passed. He gained independence to run the show as he pleased, making business deals without consulting anyone, and (perhaps more offensive to the stodgier of Parks officials), began incorporating increasingly eccentric acts into his show. They lived in a constant state of frustration. Murphy ignored safety hazards. He neglected necessary precautions to keep his audiences and performers out of harm’s way, and seemed unconcerned with the well-being of his animal acts.

As difficult as Murphy was, the 1955 season brought in an entirely new challenge to the Parks Department vision. The star attraction was Duke Ellington, famed jazz composer, and his orchestra. Ellington’s presence immediately made Department of Parks officials nervous. Interdepartmental communications included inquiries as to whether Chief Designer, Stuart Constable, was “keeping a close eye” on that year’s program. He could not “let Murphy turn this into a loud, disorderly outdoor jam session" and warned that "he always needs watching.”[8] In another Department memo, Constable reassured colleagues; “Murphy stated that the music will not be of the rock and roll type. We will however, watch this closely.”[9]

Their concern stemmed from conceptions of Ellington and his chosen idiom — jazz — as well as its successor, rock ‘n’ roll. But here Parks officials' anxieties exposed the conflicting cultural currents at work in postwar America. By the 1950s, Ellington was highly regarded. He had spent two decades cultivating a professional persona as a highly skilled, “serious composer,” and many Americans would have perceived Ellington as conservative elder statesman of the genre.[10] Characterized by historian Harvey G. Cohen as "Harlem's Aristocrat of Jazz,” Ellington’s image evaded racial stereotypes that excluded many African American performers from mass appeal. By the time of his gig with the Aquashow, Ellington had long since built a multi-racial audience and distanced himself somewhat from the Cotton Club and Harlem.[11]

But white critics from the early to mid-20th century cast jazz as a racialized primitive genre, lacking melody or sophistication. Scholar, Maureen Anderson, affirms that until 1960 many writers continued to equate their distaste for jazz with a disdain for African Americans.[12] In the case of the Parks Department’s unease, it’s possible they continued to associate Ellington with the racialized, improvisational music of the 1920s. Moreover, both jazz and rock ‘n’ roll appealed to younger generations. According to musicologist, James Wierzbicki, both genres prompted similar white assumptions of the music’s corruptive power “by conservative members of an older generation.” This may very well have applied to Robert Moses and his colleagues, whose approval of Ellington did not go beyond reasoning that he would be “OK,”[13] and who, from the early days of Flushing Meadow’s postwar improvement, expressed a wariness of the growing black population in nearby Corona.[14]

Ellington’s ties to jazz, however, were still racialized, coded as urban and understood by the Department of Parks as a potential threat coming to Queens. Particularly troubling to them seems to have been Ellington's (and jazz's) associations with musical improvisation, as evidenced by Moses' concerns about a possible "outdoor jam session." While the disorderly sounds of jazz could be contained within the walls of a Manhattan night club or by the conventions of "segregated" radio programming, the open-concept amphitheatre gave Ellington direct sonic access to hundreds of households in the vicinity of the park.[15]

Duke Ellington and his orchestra on the amphitheatre stage

New York Times, July 31 1955

Despite these concerns, Ellington's performance received positive press from around the country. In African American newspapers he was lauded not only for the performance but for his role as musical director of the all-white Aquashow.[16] For Elliot Murphy's part, he had in the end successfully recruited one of America's most respectable and refined artists for amphitheater performances. The enticement of Manhattan’s best acts to the amphitheatre, of course, had been one of the Parks Department's earliest aspirations for the venue. Their irritation with Ellington's tenure, however, suggests that only some parts of Manhattan were deemed suitable for export to the suburbs.

Elliott Murphy ran his last show in 1956. The following year George Hamid’s Aquacircus took up residence at Flushing Meadows, while Murphy looked into reviving the Aquashow at a Long Island property. It seemed the Parks Department had finally given up on prohibiting the circus. The last show at the amphitheatre was at the 1964 World’s Fair, when it hosted a similar mix of water, music and comedy acts.[17]

The clash between elite notions of entertainment and market demand exposed the complex meaning of public space, at once determined by city authorities and community residents. In the end, the battle over the amphitheatre was never resolved. Roughly ten years after the second Fair closed, the amphitheatre joined the list of municipally funded services abandoned during the fiscal crisis of the 1970s. While that decision followed many other urban disinvestments in NYC and elsewhere, Queens residents rejected the notion that their neighborhoods would be characterized by the decaying structure. They assumed the Parks Department role as gatekeepers of urban encroachment. As the structure declined and as vandals colored its walls, the Queens Valley Homeowners Association worried that should the structure be renovated, it would be used as a rock concert venue. It seemed no matter the number of single-family homes or green spaces, the use of public space continued to play a role in determining Queens’ (sub)urban character.[18]

Daniela Sheinin is a doctoral candidate in History at the University of Michigan. Her dissertation examines the many phases of Flushing Meadows-Corona Park as the catalyst for neighborhood formation, and urban and cultural change in New York City.

[1] "Water Show Recalls the Fair’s Aquacade.” New York Times, June 28, 1945.

[2] Victor Jenkins to William Latham (Park Engineer), “Attendance, Flushing Meadow Swimming Pool,” October 24 1941, box 199, folder 4 Flushing Meadow Amphitheatre (4) 1941, 102580, Queens, Department of Parks and Recreation(DPR), NYC Municipal Library and Archives(NYCMLA); Department of Parks for release, Monday July 14 1941, box 199, folder 4 Flushing Meadow Amphitheatre (4) 1941, 102580, Queens, DPR, NYCMLA; “New York’s Marine Amphitheatre,” 1941 box 199, folder 4 Flushing Meadow Amphitheatre (4) 1941, 102580, Queens, DPR, NYCMLA.

[3] Department of Parks, for release Friday July 25 1941, box 199, folder 4 Flushing Meadow Amphitheatre (4) 1941, 102580, Queens, DPR, NYCMLA; George F. Niebling to Latham, “Proposed Program for Marine Amphitheatre Opening,” July 14 1941, box 199, folder 3 Flushing Meadow Park (3) Amphitheatre, 102580, Queens, DPR, NYCMLA.

[4] Henry Colbert to I. A. Hirschmann, August 11 1941, box 199, folder 2 Flushing Meadow Park (2) Amphitheatre, 102580, Queens, DPR, NYCMLA

[5]Long Island State Park Commission, Press Release, June 27 1941, box 199, folder 3 Flushing Meadow Park (3) Amphitheatre,102580, Queens, DPR, NYCMLA; Robert Moses to George Spargo, “Pool Show - State Amphitheater,” April 25 1941, box 199, folder 4 Flushing Meadow Amphitheatre (4) 1941, 102580, Queens, DPR, NYCMLA.

[6] "New York Sees Water show at Old Fair Grounds." The Christian Science Monitor Jun 25, 1946.

[7] "Aqua-show Opens.” New York Times, July 2, 1947; Louis Calta. “Todd’s Two-A-Day Will Open Sept. 24.” New York Times, September 10, 1949.

[8] Moses to Stuart Constable, “Flushing Meadow Stadium,” May 21 1955, box 509 folder 26 Concessions (2) 1955 102890, Queens, DPR, NYCMLA.

[9] Tooley to Constable, “Elliot Murphy - Aquashow Flushing Meadow Park,” May 25 1955, box 509 folder 26 Concessions (2) 1955 102890, Queens, DPR, NYCMLA.

[10] James Wierzbicki. "Jazz." In Music in the Age of Anxiety: American Music in the Fifties, 54-74. University of Illinois Press, 2016.

[11] Harvey G. Cohen. "The Marketing of Duke Ellington: Setting the Strategy for an African American Maestro." The Journal of African American History 89, no. 4 (2004): 291-315.

[12] Maureen Anderson. "The White Reception of Jazz in America." African American Review 38, no. 1 (2004): 135-45.

[13] Moses to Stuart Constable, “Flushing Meadow Stadium,” May 21 1955, box 509 folder 26 Concessions (2) 1955, 102890, Queens, DPR, NYCMLA.

[14] James Wierzbicki. "Jazz." In Music in the Age of Anxiety: American Music in the Fifties, 54-74. University of Illinois Press, 2016; Arthur Hodkiss to Moses, September 6 1945, box 326 Folder 30 Housing-Corona 1945, 102707, Queens, DPR, NYCMLA.

[15] See Chadwick Jenkins. "A Question of Containment: Duke Ellington and Early Radio." American Music 26, no. 4 for notion of containment relating to Ellington and his music.

[16] Photo Standalone 23 -- “Three of a Kind.” Pittsburgh Courier, July 16, 1955; Larry Douglas. "THEATRICALLY... Yours." Afro-American, August 20, 1955; Larry Douglas. "Harlem to Broadway." The Chicago Defender, September 3, 1955; Luther Hill. "Duke Finds New Stars, Fame, but no 'New Ivy'." The Chicago Defender, July 02, 1955; L. C. "'Aquashow,' Rained Out Tuesday, Comes Back with a Splash." New York Times, Jun 23, 1955.

[17] Special to The New York Times. "Elliot J. Murphy, 48, Staged Aquashows." New York Times, Oct 22, 1965; "Vaudeville: Elliott Murphy Building 5,000-Seat Long Island Arena for 'all show Biz'." Variety, May 07, 1958, 63.

[18] Christopher Gray. "At Old Aquacade, Things Aren't Going Swimmingly: City Wants to Demolish Decaying Relic of '39 World's Fair." New York Times, May 28, 1995; Lynette Holloway. "Love in the Ruins; Preservationists Fight to Save Crumbling Queens Aquacade." New York Times, Jun 06, 1995.