The State Versus Harlem

By Matt Kautz

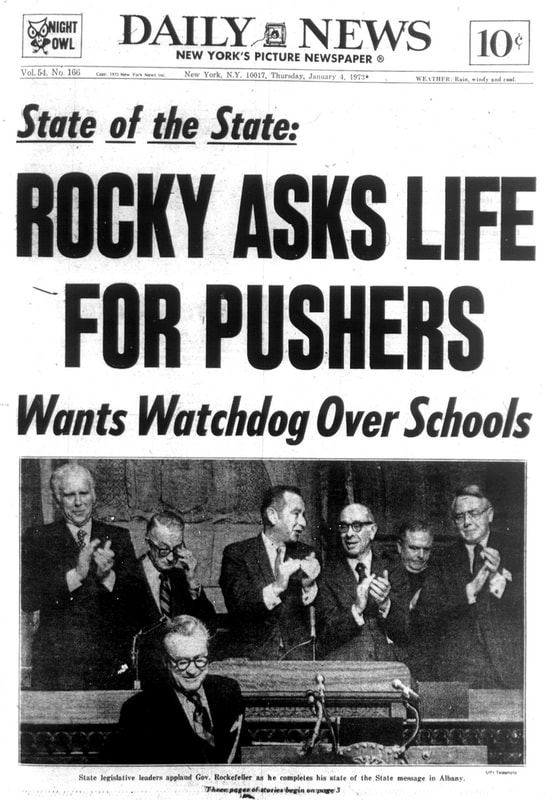

New York Daily News, January 4, 1973.

Over the past few years, Americans have paid greater attention to the harm caused by opiates and rising heroin use, specifically in white, rural areas. The New York State Department of Health has dedicated a large portion of its website to sharing statistics of opioid overdoses in the state, warning signs about what addiction looks like, information on the state’s program for monitoring doctor’s prescriptions, and how those addicted can receive treatment.

The rehabilitative approach has precedence in New York State. During the 1950s and 1960s, heroin addiction throughout the country sparked concerns similar to those today. As a result, New York state passed some of the most progressive laws in the country to support those battling heroin addiction.

However, the rehabilitative push was short-lived and movements to punish drug users and distributors culminated in the passage of the country’s harshest drug laws, the Rockefeller Drug Laws, in 1973. In large part, the criminalization of Black drug users and dealers in New York City drove this punitive turn. By looking at New York state’s response to heroin in Harlem during the 1960s, we can better understand how racialized narratives about drug addiction impact policy.

Following World War II, heroin use increased throughout the country, and much of the drug’s distribution centered in New York, specifically Harlem. The Federal Bureau of Narcotics reported in 1964 that an estimated 48,525 “active addicts” resided in the country, half of whom were believed to live in New York City.[1] Considered the “Dope Capital” of the nation, Harlem emerged as the epicenter of the heroin trade with an estimated $150 to $350 million worth of smuggled heroin stored in the community each year and some narcotics rings taking in $2,000 to $3,000 a day.[2] As Eric Schneider argues in Smack: Heroin and the American City, marginalized communities in major cities, like Harlem, became central nodes for heroin distribution because the withdrawal of capital and public disinvestment in these neighborhoods sparked demand for narcotics. The lack of adequate housing, schools, jobs, and other public resources perpetuated the demand, which then increased supply from foreign producers, turning the region into an even larger drug center. In many respects, the drug trade provided economic opportunities otherwise unavailable to Harlemites due to racial discrimination and deindustrialization in postwar Manhattan.[3] As attendees at a Harlem neighborhood conference on narcotics addiction saw it, “unemployment, poverty, poor housing, the oppressive strangulation of ghetto life and its constriction of opportunities for creative expression” as well as the large profits in the illicit industry fostered the growth of the heroin trade in the community.[4]

Parents and schools provided Trapped! and other comics like it to young people in hopes of deterring drug use.

During the 1950s, heroin use continued to rise, and state legislatures and suburban parents paid increasing attention to the possibility of young, suburban white addicts. The focus on heroin afflicting white youth manifested in comic books like Trapped and Holiday of Horrors as well as stories in journalistic publications like Dope, Inc. and Newsweek. Each publication followed the same script, in which a well to-do white suburban youth began his or her narcotic journey by trying marijuana, escalating to heroin, turning to violence (boys) or prostitution (girls), and then eventually dying from an overdose.[5] The increasing concern about heroin expanding from the city to the suburbs sparked a new tenor in drug prevention and public policy. The greatest change came in 1962 when New York’s state legislature passed the Metcalf-Volker Act, which allowed drug users arrested on minor charges of use or possession of narcotics to undergo treatment at a state hospital, rather than serve time in prison. After completion of the intensive program, offenders were to be supported with an aftercare program. Provided an offender successfully completed this care, he or she would have their criminal record expunged. This legislation also allocated funding for a narcotics office to expand the state’s drug research, treatment, and aftercare programs as well as establishing a state council to help inform future policy.[6] While the passage of the Boggs Act in 1951 by the federal government increased the severity of punishments for drug distribution and established mandatory minimums, the Metcalf-Volker Act established drug addiction as a mental illness, rather than a crime. As a result, the state placed its

emphasis on treating addiction, rather than policing distributors.

The concern for white youth falling victim to heroin became the driving force, not only behind this legislation, but also the distribution of state-sponsored rehabilitation centers that emerged as an outgrowth of the Act. The state deployed six rehabilitation hospitals with only one of those hospitals operating in the city. Although Harlem was the central node in the heroin trade, no state treatment centers were placed in the community.[7] A puzzling fact given that between 1950 and 1961, more than 46 percent of recorded heroin overdoses in New York City happened in Harlem.[8]

However, the belief in rehabilitation that led to the passage of the Metcalf-Volker Act soon waned. By 1965 Governor Rockefeller had already called the law a failure, citing its inability to cure addiction, its expense, and the number of arrested addicts who opted to forego rehabilitation. These critiques emerged within a hardening political context. Reports of increasing crime combined with heightening resistance to the Civil Rights Movement became the foundation for the “law and order” Republican platform advanced by Barry Goldwater in the 1964 presidential election.[9] Rockefeller, who had his own presidential ambitions, was losing ground within the political mainstream of his party, and his rehabilitative approach to narcotics stood out against the party’s “law and order” platform.

Responding to the demands of his party and the panic surrounding increases in crime and perceptions of urban decay, Rockefeller made altering his policies on drugs a central plank of his 1966 gubernatorial campaign. However, although conservative politicians throughout the country, including Rockefeller, centered their “law and order” rhetoric on urban communities of color, increasing drug use in New York during the mid-1960s was not in the cities as much as it was in the suburbs. In Suffolk County, arrests for selling heroin and marijuana increased 260 percent between 1965 and 1966.[10] And, in the first ten months of 1966, Nassau police made 505 drug-connected arrests compared to 161 the previous year.[11] The increase in arrests of these predominantly white communities deepened worries over the sale and use of drugs by white suburbanites with a special concern for students on college campuses.[12] Although the new focus of suburban law enforcement on drug distribution explained part of this rise in arrests, the increased use of narcotics could not be denied. During 1965, six Long Island youth died from some form of drug intoxication, but by 1972 more than fifty people had died from a drug overdose, half from heroin. For those who had died from heroin, the average age of death had been less than twenty-three years old.[13] In this political context, Rockefeller sought a policy that matched calls for “law and order,” but also provided rehabilitative pathways. In essence, Rockefeller needed a message that spoke to the urge of rehabilitating white drug users, while also increasing the power of the criminal justice system in the regulation of narcotics distribution.

Therefore, in 1966, Rockefeller issued a referendum on the Metcalf-Volker Act by calling for forced treatment of drug addicts (whether or not they had committed a crime), stiffened prison sentences for narcotics “pushers,” and increased funding for local law enforcement.[14] Rockefeller declared “an all-out war on crime and narcotics addiction,” adding “This is war, and every addict should be enlisted in the battle with himself and the drug that imprisons him.”[15] Departing from his previous rehabilitative rhetoric of 1962, Rockefeller emphasized connections between addiction and crime claiming that “narcotics addicts are responsible for one-half of the crimes committed in New York City alone.”[16] Though heroin existed throughout the city, Rockefeller narrowed the scope of criminal connections and narcotics to Harlem. In a special address given on television called The State Versus the Addict, Rockefeller framed addicts’ need for rehabilitation through the story of an affluent white user while framing the law enforcement provisions of the bill by discussing the estimated 50,000 heroin addicts in Harlem.[17]In 1966, having successfully coded the rehabilitation and law enforcement aspects of the act in racial terms, Rockefeller passed the Narcotics Addiction Rehabilitation Act (NARC).

Rockefeller’s change in rhetoric and this new legislation deepened an atmosphere of hostility towards drug “pushers” and laid the groundwork for a punitive turn targeted at Black and Puerto Rican drug dealers. This turn hinged on constructing a Harlem riddled with criminals and hopeless addicts, while preserving the innocence and respectability of white drug users. Reporters, researchers, and politicians accentuated this turn with loaded descriptions and analyses of Harlem’s narcotics problem. They projected drug addiction and narcotics sales as endemic to Harlem and painted Black heroin victims as criminals and products of circumstance, unable to escape the ghetto. The explicit focus on Harlem youth played upon assumptions of young, black male criminality while also emphasizing racial narratives of urban decay, and it implied a stasis of immorality and hopelessness that could not be overcome, only contained.

Despite all the focus on Harlem and its youth, the state did little to support rehabilitative efforts in the community. Instead, community members had to create their own rehabilitation organizations and treatment centers. In 1963, the Harlem Neighborhood Association (HANA) held a conference focused on the connected web of overcrowded housing, education, and mental health to alleviate addiction in the community, which led to calls for a narcotics rehabilitation hospital in the community, education programs about the problems of addiction, the involvement of ex-addicts in treatment programs, and a partnership with the Department of Welfare for ways to better facilitate assistance to addicts.[18] In the mid 1960s, Reality House, a new treatment center founded by former heroin addict Leroy Looper, trained and employed former addicts to assist in the rehabilitation efforts of other addicts, strengthened addicts’ ties to their communities, and supplied jobs to recovering addicts since unstable employment would often result in relapse or crime.[19] Reality House received minimal state funding and received over 60 percent of its operating expenses through private contributions. In 1970, another organization comprised of heroin addicts and community leaders, United Harlem Drugfighters, stormed in and took over an unused ward of the Harlem Hospital to treat addiction with flexible programs that allowed addicts to continue to work while getting treatment.[20] Within the first two weeks, nearly 300 Harlemites received treatment that they were unable to get elsewhere. The grassroots’ protest eventually convinced the city to help fund treatment at Harlem Hospital. A different community group set up a self-help commune in an abandoned warehouse for recovering addicts. The National Economic Growth and Reconstruction Organization (NEGRO), a Black-run nonprofit funded through the sale of Economic Liberty Bonds, which ranged from 25 cents to $10,000 and returned 6.5 percent annually, opened a treatment center called Freedom House where residents received treatment twice a day from local doctors and worked with each other to find stable employment.[21]

These local initiatives lacked significant levels of state funding as the majority of funds went to developing hospitals in white communities in both the city and the state. In 1966, the state purchased Mount Morris Park Hospital (the only hospital in Harlem the state would purchase for addiction treatment) to house a treatment center in Harlem with sixty-one beds.[22] However, that same year, the state purchased four other hospitals in lower Manhattan between tenth and fortieth streets (all with over 150 beds each) totaling 1,078 beds for treatment.[23] In 1971, it was considered a windfall when the governor agreed to send $500,000 in funding to Harlem community treatment centers, despite making up less than one percent of the state’s total budget for narcotics treatment. That same year, the state invested over seven million dollars in a treatment center in lower Manhattan’s Gramercy Park.[24] In essence, NARC’s rehabilitative focus on white drug users consolidated resources in white communities while providing a disproportionately small share to Harlem, where the heroin crisis was just as severe, if not more so.

It should be noted that the only Harlem community initiative to receive significant levels of state funding stands out for its staggering success and longevity.The Addicts Rehabilitation Center (ARC) established in 1957 eventually became the only state-accredited residential treatment center in Harlem. Though the building only had the capacity to serve forty patients during the 1960s, it regularly served over one hundred. The ARC also had a special juvenile program targeted at helping youth fight their addiction. In part, ARC’s rehabilitative power emanated from James Allen, the man who oversaw the program. A former addict himself, James Allen overcame his ten-year addiction to dedicate his life to helping other addicts. Having been locked up twice before, Allen acknowledged that jails didn’t provide training to help addicts stay away from drugs after release, nor did it treat addiction. As Allen said, “Most people have already conceded that addicts are sick people. So why put them in jail? You never get police for sick people.”[25] Favoring rehabilitation over incarceration, James Allen hired former addicts to administer treatment, provided shelter to those fighting their addiction, and created job opportunities for those in recovery. In an attempt to treat the patient holistically, Allen also famously began a choir as a means to help recovering addicts.

However, ARC was an exception as state funds overwhelmingly went into New York’s white communities. In the face of this disparate funding, Governor Rockefeller constantly referred to the heroin problem in Harlem as a justification for the limits of rehabilitative reforms and the need for greater policing. In late January 1973, Rockefeller held a televised news conference to advocate for more punitive drug laws and to articulate the framework for these laws. Despite the law encompassing the entire state, Rockefeller took the stage with five guest speakers, all of whom hailed from Harlem, to give the “street point of view.”

Using Harlem as a canvas to show what the legislation would mean, each speaker told a story meant to be representative of the state but confined to the streets of Harlem. After the speakers from Harlem finished, Governor Rockefeller again took the stage to further explain the need for these laws, emphasizing the high costs for minimal returns. The irony of Rockefeller’s critique of state investment without returns is striking. While the state of New York may have spent more than $11,000 a day on treatment for each addict over the last six years, as Rockefeller claimed, none of those public funds went to a state-run residential facility in Harlem and few went to local treatment centers in the neighborhood. State subsidies for treatment, including methadone maintenance, were deployed in greater proportion to white communities in lower Manhattan and rural, upstate New York, despite the reported primacy of heroin in Harlem. In effect, the community so ravaged by the narcotics epidemic was brought center stage as a startling example of state failure, despite receiving little state aid to fight addiction through rehabilitation. And, it was this portrait of Harlem, using easily digestible, imagined constructions of criminal pushers, identified as poor Black youth from Harlem, that cemented the support for increased law enforcement and further withheld state support to those battling addiction in Harlem.

Although the national conversations surrounding drug distribution and addiction has changed significantly since the passing of the Rockefeller Drug Laws, policing practices and rehabilitative efforts still follow racial lines. Even in New York City, where marijuana has been decriminalized, African Americans are arrested at eight times the rate for marijuana possession as white New Yorkers. In addition to these disparities in marijuana arrests, other research has indicated that resources fighting the opioid crisis have also been disparate. The severity of the opioid crisis cannot be understated and deserves state and municipal intervention. However, New York state has a history of making decisions about state investment in rehabilitation and policing efforts along geographic and racial lines, and, given the current narrative of the opioid crises, those divisions are important to remember.

Matt Kautz is a doctoral student in History and Education at Teachers College, Columbia University. Prior to graduate school, Matt was a high school teacher in Detroit and Chicago. His current research focuses on the changes in school discipline during the era of desegregation and how these punitive policies made urban schools central to the rise of the carceral state.

Notes

[1] Eric Schneider, Smack: Heroin and the American City (Philadelphia: University of

Pennsylvania Press, 2011), 10.

[2] “US Attorney Calls Harlem ‘Dope Capital,’” New York Amsterdam News, November 30,

1957.; “3 Held in Heroin Sales: Youths Branded Wholesalers for One-Third of Harlem,” New York Times, November 7, 1954.

[3] Schneider, Smack, 202-203.

[4] “Neighborhood Conference on Narcotics Addiction (1963)” Harlem Neighborhoods

Association Records, 1941-1978, Box 5, Folder 4. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.

[5] Ibid., 51-55.

[6] Arthur Pawlowski, “New York State Drug Control Policy During the Rockefeller

Administration, 1959-73” (PhD Diss., State University of New York at Albany, 1986), 85.

[7] Jessica Helen Neptune, “The Making of the Carceral State: Street Crime, the War on Drugs,

and Punitive Politics in New York, 1951-1973” (PhD Diss., University of Chicago, 2012), 94.

[8] Milton Helpern and Yong-Myun Rho, “Deaths from Narcotism in New York City: Incidence,

Circumstances, and Postmortem Findings,” New York State Journal of Medicine66, no. 18 (1966), 198.

[9] Charles Moh, “Goldwater Links The Welfare State To Rise in Crime,” New York Times,

September 11, 1964, 1.; Dan Berger, “Lessons in Law and Order Politics,” Black Perspectives,August 9, 2016. https://www.aaihs.org/lessons-in-law-and-order-politics/.

[10] Maureen Neill and Linda O’Charlton, “Drug Arrests Rocket in Suffolk,” Newsday, March 9,

1966, 5.

[11] Bob Greene, “Dope Arrests Double, But LI Problem Grows,” Newsday, November 30, 1966,

4.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Bob Greene, “Drugs Spread among LI Teens: Drugs Spread Among LI Teens” Newsday, January

4, 1966. Scheider, Smack: Heroin and the American City, 157.

[14] Sydney Schanberg, “Rockefeller Signs Bill on Narcotics: Names Head of Controversial

Program for Addicts,” New York Times, April 7, 1966, 35.

[15] Bernard Weinraub, “Confinement of Addicts proposed by Rockefeller,” New York Times,

February 24, 1966, 1.

[16] Ibid., 24.

[17] Neptune, “The Making of the Carceral State,” 102.

[18] “Neighborhood Conference on Narcotics Addiction (1963)” Harlem Neighborhoods

Association Records, 1941-1978, Box 5, Folder 4. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library

[19] Peter Khiss, “8 Narcotics Addicts in Harlem Helping Each Other 'Go Straight',” New York

Times, December 4, 1967, 52.

[20] “Harlem Addicts Turn to Hospital,”New York Times, July 27, 1970, 55.

[21] “125 Harlem Drug Addicts Set Up Self-Help Center in Old Warehouse,” The Baltimore

AfroAmerican, January 3, 1970, 18.

[22] “State Buys Mount Morris Pk. Hospital,” New York Amsterdam News, October 15, 1966, 1.

[23] Murray Schumach, “Day of Compulsory Care Nears for Wary Addicts,” New York Times,

March 27, 1967, 1.

[24] “State Grants 7.9-Million for Methadone Aid Here,” New York Times, September 23, 1971,

73.

[25] Malcolm Nash, “Ex-Addict Now Works to Help Others Drop Habit,” New York Amsterdam

News, November 9, 1963.