The Upper Barracks: Military Geography in the Heart of New York

By John Gilbert McCurdy

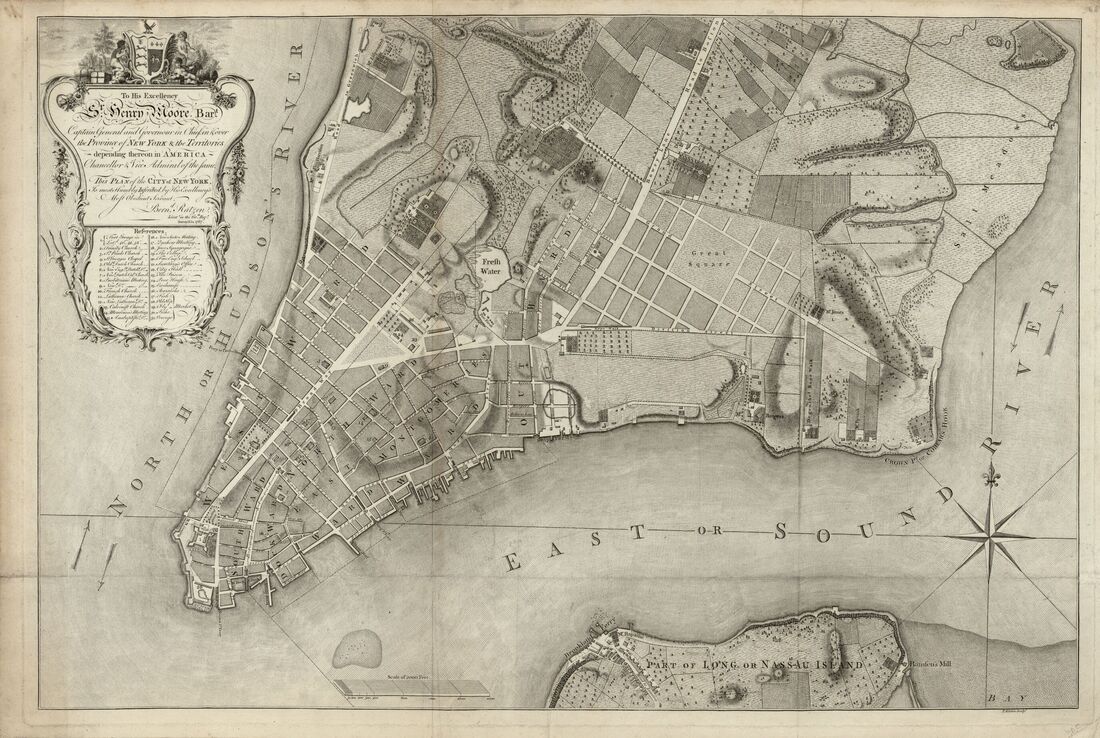

In October 1757, the New York Common Council authorized the construction of the Upper Barracks. It was to be a massive building: 420 feet long and 20 feet wide, consisting of two stories and enough space to sleep 800 men. Such a structure dwarfed anything else in the city; it was longer than a city block and twice as large as Trinity Church. The Committee for the Building of the New Barracks situated the barracks at what was then the northern edge of New York, placing them on the city common where Broadway split into roads leading to the suburbs of Greenwich Village and the Bowery. As carpenters set to work, the Upper Barracks claimed a privileged position in New York, placing the city under the watchful gaze of the British army.

Barracks at Antigua, 1760s. These barracks were similar to the Upper Barracks built in New York. British Library Online.

At a time when New York measured about one square mile and consisted of around 15,000 inhabitants, the Upper Barracks lorded over the city. It may also be difficult to imagine the place of military infrastructure within a city that has so long been without one. Today, Castle Clinton is a quaint artifact enjoyed on a leisurely stroll through Battery Park; soldiers are occasional visitors, not permanent residents. Indeed, the prospect of an army in New York City seems antiquated in a century when the worst attacks have come from the sky.

Yet late colonial New York City was defined by its military geography. Scholars have interrogated the importance of war to notions of place, but little of this analysis has been placed in a historical context. Obsessed with an “everywhere war,” we fret that no place is safe from violence. But we forget that cities like New York were once surrounded by palisades, armed with a massive fort, and filled with professional soldiers. Military geography penetrated all aspects of life as armed soldiers walked the streets, sparred with civilians, and even quartered in private houses. Remembering such realities reveals the how much we take for granted the absence of military geography in modern American life. The Upper Barracks was part of process of isolating and ultimately removing military geography from New York City.

Need for Barracks

The Upper Barracks was not the first military infrastructure in the city. As the name suggests, there were already barracks at the southern edge of the city. Since the founding of New Amsterdam in the 1620s, a massive fort had sat on the tip of Manhattan to protect the city from attack. When the English invaded in 1664, the conquering troops found the fort’s barracks too small, so they quartered in the homes of the inhabitants. The army soon shrank enough to squeeze inside Fort George, and British troops became a permanent part of New York.

John Carwitham, “A View of Fort George with the City of New York from the SW” (1736). Library of Congress.

In the 1750s, the number of soldiers in New York swelled again when Britain clashed with France in the Seven Years’ War. In the fall of 1756, a battalion of the Royal American Regiment arrived in New York seeking winter quarters and new recruits. Although the colonial government attempted to detain the redcoats on Governor’s Island, this was not a long term solution. Accordingly, in December 1756, New York passed a quartering act directing British troops in the city to barracks and public houses. However, “there shall not be a sufficient Number of such houses,” then the soldiers were to be quartered “in such private Houses.” The growing intensity of the war made many New Yorkers fear that troops would soon be forcibly quartered in their homes, so they authorized the Upper Barracks.

New Yorkers in the 1750s understood the Upper Barracks as a means of protecting their homes from quartering. Fearful for their city and loyal to King George II, New Yorkers welcomed British soldiers as defenders, but they loathed quartering troops in their houses. The construction of barracks resolved this dilemma. Ideas of a “right to privacy” were still nascent in the 1750s, but the Upper Barracks were an early attempt to accomplish this. Indeed, New Yorkers did not protest a special tax for the barracks or the cost of supplying their inhabitants. As one colonist noted in the New-York Gazette, “building a large Number of Barracks…is much more equitable and just, than to have them billeted on the Inhabitants.”

Oddly enough, the Upper Barracks emptied of British soldiers shortly after they were completed. By 1759, the main theater of the Seven Years’ War had shifted to Canada and the military presence in New York scaled down to a skeleton crew. The Common Council opened the Upper Barracks to charity, granting one room to a weaver named Hill, “he having lately come from Europe, and being unable at present to provide for himself and family elsewhere.”

But the presence of barracks in New York City made the city attractive to military planners once the war ended. In May 1766, Commander in Chief General Thomas Gage ordered the 46thRegiment of Foot into the Upper Barracks and asked the colonial government “to provide sufficient quarters, bedding, etc.” according to the recently-passed Quartering Act.

Life in the Barracks

For the next decade, the Upper Barracks was populated by various regiments of British regulars, averaging between three and five hundred enlisted men and officers. Such a concentration of military personnel made it the headquarters for the British army in North America. Inside the barracks, trials for “disrespectfull & opprobrious language” convened in the officers’ guard room, while another room held a private awaiting trial. Punishment for such crimes was carried out in the green space in front. When Private Richard Smith was found guilty at a court martial in 1768, General Gage ordered his punishment of fifty lashes “be inflicted by the Drummers of this Garrison on the Parade at the upper Barracks.”

City Hall park indicating where the Upper Barracks once were.

Life inside the Upper Barracks was spartan. The Common Council demanded that twenty men cram into a room measuring twenty-one feet square, but as this would have allowed less space per soldier than any barracks in Britain, the army persuaded the city to relent. Nevertheless, soldiers slept two men to a bed and shared common space in each room. Wives and children joined the soldiers in the Upper Barracks. Although the army provisioned these dependents, it expected women to cook, clean, and serve as nurses in exchange for their food.

British soldiers had to prepare their own meals, so each room contained a fireplace and table with benches, as well as a variety of platters, bowls, and mugs. Common decency necessitated chamber pots and racks for the men’s clothes and arms, while cold winter nights demanded firewood and candles. To ward off sickness, the soldiers received salt, vinegar, and small beer, a beverage with very low alcohol content that took the place of polluted water.

The cost of these supplies fell on New York taxpayers. The Quartering Act of 1765 mandated that the Americans supply soldiers in their colony and New York complied, although not always willingly. Between 1767 and 1774, the colonial assembly appropriated more than £12,000 New York currency for quartering expenses, often the largest portion of the colony’s annual budget.

Barracks and the City

The Upper Barracks influenced the tenor of New York City. The neighborhood around the structure was rapidly gentrifying in the 1760s with the opening of St. Paul’s Chapel and King’s College (later Columbia University) a couple blocks away. Yet these elite institutions had to compete with nearby taverns and brothels that catered to the troops. The redcoats also marched down Broadway to Fort George and wandered the streets in search of amusements. One night in June 1766, a group of inebriated officers smashed a street lamp, and when a local innkeeper rebuked the officers, they struck him with their swords and proceeded to down Broadway, destroying more lights as they went.

British soldiers could also be a source of law and order. When a theater opened on John Street in December 1767, supporters of New York’s nascent Broadway district feared that evangelicals would demolish the playhouse. In response, General Gage dispatched a sergeant, a corporal, and twelve men from the 16thRegiment “to mount guard at five this evening at the playhouse” and ordered that “this guard to be continued as often as necessary till further orders.”

In effect, the Upper Barracks made it possible for soldiers and civilians to share New York. By keeping troops out the colonists’ homes, the barracks made troops palatable to the colonists. Historians have often focused on the negative interactions of New Yorkers and redcoats and the colony’s resistance to the Quartering Act, both of which predicted American independence. However, this teleological perspective obscures the fact that harmony and accommodation were common in late colonial New York City.

To be sure, the Upper Barracks was also a target for colonists when New Yorkers sought to resist their taxation without representation by Parliament. In May 1766, the New York chapter of the Sons of Liberty erected a liberty pole in front of the soldier’s quarters to celebrate the repeal of the Stamp Act two months earlier. The liberty pole was a pine mast topped with a banner proclaiming “liberty.” For three months, British soldiers marched underneath the pole until day in August 1766, members of the 28thRegiment chopped it down. Colonists responded with by attacking soldiers with “abusive language” and chunks of brick, before they “surrounded the barracks, and vented so much abuse.”

The ground in front of the Upper Barracks again became a place of conflict in early 1770 when colonists gathered to protest the Quartering Act. Once again, British soldiers chopped down a liberty pole and once again colonists and troops came to blows in a series of confrontations that came to be known as the Battle of Golden Hill. As American opinion of the British governance soured, the Upper Barracks came to be seen by New Yorkers with increasing hostility. Following flashpoints like the Boston Massacre, the number of protests in front of the barracks grew.

Finally, when news reached New York that militiamen and redcoats had exchanged fire at Lexington and Concord in April 1775, New Yorkers turned their attention to the Upper Barracks and the 18thRegiment quartered then there. Colonists tempted soldiers to renounce the king, and when this proved effective, Major Isaac Hamilton removed the troops to a warship in the harbor. When the British soldiers withdrew, New Yorkers swarmed the Upper Barracks.

Absence of Barracks

The Upper Barracks retained their original purpose during the American Revolutionary War as American and then British armies took control of the city. However, when the last British troops departed in November 1783, New Yorkers’ opinion of military quarters among civilians lost its currency. At first, the Common Council rented out the Upper Barracks as apartments, but by the time George Washington arrived as the first president of the United States, the building was “going to ruin for want of Repair.” In January 1790, the city voted to demolish of the buildings “formerly occupied as Barracks.” The city repurposed the land for municipal purposes, later erecting the City Hall and Tweed Courthouse on the site.

The rise and fall of the Upper Barracks invites us think about the role of military geography in the invention of the American city. Although temporary barracks rose again in New York during the Civil War, soldiers have never again been a permanent part of the city. We might observe that New Yorkers simply wanted to expel the British army, but it is interesting that US troops never occupied the city after independence. The lesson of New York’s Upper Barracks was that US citizens had the right to be protected from the military power of their own nation. As the US Army removed to distant places like West Point, New Yorkers came to imagine their city as a place of peace.

John Gilbert McCurdy is Professor of History at Eastern Michigan University and author of Quarters: The Accommodation of the British Army and the Coming of the American Revolution, from which this blog post is taken.