“To Help People Learn to Fight”: New York City’s Mobilization for Youth and the Origins of the Community Action Programs of the War on Poverty

By Tamar W. Carroll

Henry Street Settlement Collection, Social Welfare Archives, University of Minnesota.

In 1962, the pioneering social work agency Mobilization for Youth (MFY) began its anti-juvenile delinquency program in New York’s Lower East Side. Within two years, energized by the civil rights movement, residents and staffers together transformed MFY from a social service program into a hotbed of direct action organizing. Low-income African American and Puerto Rican mothers, together with MFY organizers, generated social movements that forever changed New York City and shaped the national War on Poverty. As Stanford Kravitz, an architect of the Economic Opportunity Act observed, their efforts “escalated long-festering problems into wide public view, so that discussion of them as critical national issues could no longer be avoided.” In doing so, MFY participants and staff “prepared the ground” for the establishment of the Community Action Programs (CAPs) of the War on Poverty, which was launched by President Lyndon Johnson in 1964.[1]

This is the first of three excerpts we are publishing from the author's new book Mobilizing New York: AIDS, Antipoverty and Feminist Activism (University of North Carolina Press: 2015).

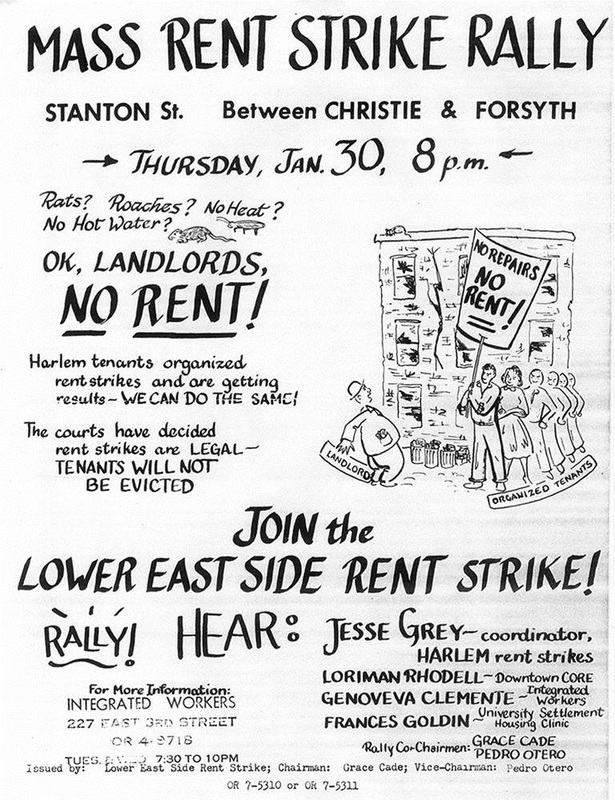

By the mid-1960s, many of New York’s African American and Puerto Rican residents were “fighting mad,” as one Mobilization for Youth social worker described them.[2] The public schools remained segregated; decent, affordable housing was in desperately short supply; and police brutality inflamed the wounds inflicted by inequality and poverty. The school integration campaign’s inability to win improvements had led Rev. Milton Galamison to orchestrate the massive boycotts of February and March 1964; similarly, the fair housing movement’s frustrated efforts to lessen residential segregation and secure more public housing for African Americans and Puerto Ricans prompted civil rights activists to embrace more disruptive tactics. In the fall of 1963, housing activist Jesse Gray organized tenants in Harlem for a coordinated rent strike designed to draw attention to the dismal conditions of the tenement apartments and to pressure city officials to enforce the building code and to fund more public housing. As development czar Robert Moses constructed his $1 billion 1964–65 World’s Fair complex at Flushing Meadows, beckoning tourists from around the world, Gray suggested that Moses include a “guided tour of the ghetto in Harlem” for visitors to witness the tremendous gulf between the vision of consumer opulence and Space Age progress on display at the fair and the reality of dismal living conditions for so many of the city’s African American and Puerto Rican residents.[3]

Puerto Ricans and African Americans paid more than white New Yorkers for their apartments and yet endured decrepit conditions, including lack of heat and hot water, no bathroom facilities, leaky ceilings, and rats, which posed health problems; in 1962 alone, the City Bureau of Sanitary Inspections reported 530 children bitten by rats in their homes. Landlords often left doors unlocked, allowing narcotics addicts to enter, stash their drugs in holes in the walls, and occupy the stairways and halls of tenements, which quickly became unsanitary; one reporter described them as feeling “like a dank passage to despair.”[4] Poor tenants faced a double bind, as the city welfare department would withdraw rent allowance if the building a tenant lived in was declared hazardous.[5] In fear of losing their benefits should they bring a landlord’s deficiencies to city authorities, renters had little recourse but to make do….

African American activist Jesse Gray, director of the Community Council on Housing, rose to prominence in the fall of 1963 and winter of 1964 after successfully organizing 225 tenements in Harlem with more than 2,000 residents to withhold rent payment until landlords completed repairs. Gray, one of 10 children, was born in a rural town outside of Baton Rouge, Louisiana; attended college at Xavier University, a black Catholic institution in New Orleans; and joined the Merchant Marine, where he became a leader in the left-wing National Maritime Union, which championed racial equality and rank-and-file leadership. According to an interview with his good friend, fellow National Maritime Union member and important civil rights leader Jack O’Dell, Gray’s political consciousness was shaped by both his international travels, which exposed him to movements for social justice such as the Tenants’ Movement in Scotland, and his study of Marxism in the 1950s.[6] Gray had begun organizing tenants in Harlem in the 1950s; in 1963, seeking to apply greater pressure on city officials, Gray asked tenants to bring rats, living or dead, to court and to City Hall with them as ammunition in their battles with landlords and city bureaucracies. He also organized the “Rats to Rockefeller” campaign in which tenants mailed four-inch rubber rats to the governor and demanded more state support for public housing.[7]

In the fall of 1963, inspired by Gray’s success, MFY shifted from supporting individual staff members in their actions against specific landlords to joining a citywide movement for fair housing conditions, rent control, an end to residential segregation, and the construction of adequate public housing for low-income families. That winter, MFY changed its housing clinics to Tenants’ Councils, designed to be membership organizations composed of building and block tenant leadership. The goal, MFY organizer Ezra Birnbaum explained, was to “convert as much of the service role as quickly as possible into direct action techniques, rent strikes, et cetera.” While MFY staff members would still play a role in cultivating leadership, their objective was to form a resident-controlled movement of renters in the Lower East Side. Moreover, Birnbaum announced, MFY workers would “no longer work with individual tenants unless the tenant is prepared to help organize his building. Only emergencies will be exceptions to this.”[8] This directive marked a change in the conception of the role of the agency’s social workers; no longer merely advocates, they were instructed to incite and participate in direct-action protests….

Following their participation in the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, MFY staff and Lower East Side residents alike were swept up in the civil rights movement. According to Frances Fox Piven, “As people showed themselves to really be ready and angry, the community organizing component of the project became much more important. . . . MFY professionals were learning and changing as the political situation changed.”[9] Working with Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) leaders from the Harlem, New York University, Downtown, and Brooklyn chapters, MFY staff members helped organize rent strikes against slum landlords. In order to meet the needs of their largest constituency—low-income women of color—MFY staffers formed welfare rights groups. Lawyers in MFY’s new Legal Service Division pressed the city courts to uphold the due process rights of their clients and advanced test cases that led to reforms in housing and welfare policy….

Property owners and city officials perceived low-income Lower East Side residents’ calls for fair treatment—to receive what they were entitled to, by law—as attacks on themselves personally and on the social order. In the late summer of 1964 The Daily News, in conjunction with city councilman Paul Screvane, led a campaign against MFY, charging the organization with harboring communists and fostering subversion and, later, with mismanagement of public funds. Amid the still-heated Cold War atmosphere, the city government, New York State, and the U.S. Senate all launched inquiries into MFY’s alleged communist ties.

While the agency was eventually cleared of charges regarding communist influence and misuse of funds, “the crisis,” as MFY staffers later referred to the period between 1964 and 1965, had a chilling effect on the organization. The President’s Committee on Juvenile Delinquency requested the resignations of MFY’s top-level staff and installed a new head, Bertram Beck, with the directive to quell the community organizing program. The organization dissolved by 1970, but not before it left significant legacies, including the Community Action Programs of the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, the welfare rights movement, and the legal services movement. Participation in MFY’s community organizing proved to be a radicalizing experience for both residents and staff members, many of whom went on to become lifelong activists. MFY organizer Marilyn Bibb Gore reflected that “one of the greatest things that MFY did was help people learn to fight.”[10]It fostered several social movements that changed the city’s political and social landscape and inspired other activists across the nation.

Tamar W. Carroll is Assistant Professor of History at Rochester Institute of Technology. This is the first of three excerpts we are publishing from her new book, Mobilizing New York: AIDS, Antipoverty, and Feminist Activism (UNC Press, 2015).

[1]Administrative History of OEO, vol. 1, Part II, pp. 154-157, Lyndon Johnson Presidential Library, Austin, TX.

[2] Francis P. Purcell and Harry Specht, "Selecting Methods and Points of Intervention in Dealing with Social Problems: The House of Sixth Street," in Community Action Against Poverty: Readings From the Mobilization Experience, ed. George A. Brager and Francis P. Purcell (New Haven: College and University Press, 1967), 231.

[3] Martha Biondi, To Stand and Fight: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Postwar New York City (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003), 112-36; Mandi Isaacs Jackson, "Harlem's Rent Strike and Rat War: Representation, Housing Access and Tenant Resistance in New York, 1958-1964," American Studies 47, no. 1 (2006). George Tood, “Gray: Have Fair Visitors Visit Slums in Harlem,” Amsterdam News, 22 Feb. 1964, p. 46.

[4] Homer Bigart, “Harlem Tenants Cope With Cold,” New York Times, 1 Jan. 1964, p. 1.

[5]McCandlish Phillips, “Harlem Tenants Open Rent Strike,” New York Times, 28 Sept. 1963, p. 1; Homer Bigart, “Rent Striker Bids for Red Cross Aid,” New York Times, 25 Dec. 1963; Joshua Freeman, Working Class New York: Life and Labor Since World War Two (New York: The New Press), 2000: 183-85.

[6] Roberta Gold, "City of Tenants: New York's Housing Struggles and the Challenge to Postwar America, 1945-1974" (University of Washington, 2004), 141-42. According to Gold’s interview with O’Dell, both O’Dell and Gray joined the Communist Party in the 1950s. Robert Sullivan, in contrast, writes that Gray was “probably not” a Communist, although he was certainly dedicated to promoting radical social change. Robert Sullivan, Rats: Observations on the History and Habitat of The City's Most Unwanted Inhabitants (New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2005), 66.

[7] Martin Gansberg, “Tenants in 34 Tenements Join Growing Rent Strike in Harlem,” New York Times, 2 Dec. 1963, p. 30; “Powell Urges City Hall March to Support Harlem Rent Strike,” New York Times, 16 Dec. 1963, p. 27; “Harlem Slum Fighter,” New York Times, 31 Dec. 1963. Jackson, "Harlem's Rent Strike and Rat War: Representation, Housing Access and Tenant Resistance in New York, 1958-1964," 66-67.

[8] Ezra Birnbaum, “The Community Organization Housing Program: Report to the Ad Hoc Committee on Community Organization,” January 7, 1964, p. 8, U.S. Senate Internal Security Files, Box 157, Folder, “MFY 1965-1968,” National Archives, Washington, D.C. See also “Harlem Boycott on Rents Spreads,” New York Times, 5 Nov. 1963, p. 23, and “MFY Tenant News,” vol. 1, April 10, 1963, Frances Fox Piven Collection, Sophia Smith Archives, Smith College, Northampton, MA.

[9]Frances Fox Piven, interview by Noel Cazenave, transcript of audio recording, pp. 23-24, May 28, 1992, War on Poverty Project, Columbia University Oral History Archives.

[10] Marilyn Bibb Gore, interview by Tamar Carroll, transcript of audio recording, April 6, 2005, New York City Women Community Activists Oral History Project, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College.