Transatlantic Radicalism in Early National New York

By Sean Griffin

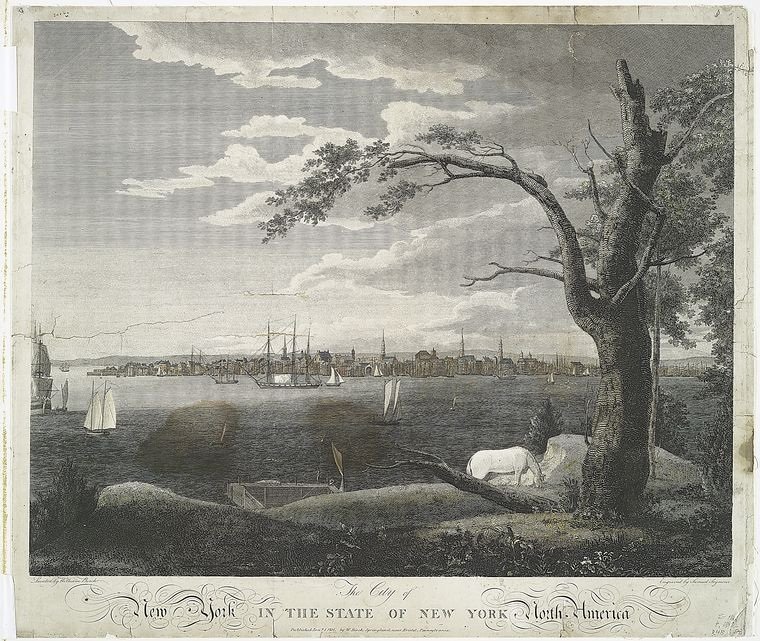

New York City has long been considered a hotbed of radical political ideas, as well as a cosmopolitan center of culture and commerce. But while the roots of the latter have been traced back to the city’s origins as a Dutch trading post with a decidedly commercial outlook and a polyglot population, fewer historians have explored the origins of the city’s radical political culture.

Indeed, what Eric Foner has termed an “American Radical Tradition” could be said in many ways to have originated in New York (although Philadelphia remains a strong contender). Most famously, Thomas Paine, the subject of one of Foner’s early works and the originator of what has been called the “Paineite radicalism” of the Anglo-Atlantic world, made the city his home between 1806 and his death in 1809.[1]

By that time, Paine had been disowned by his former revolutionary colleagues in both the United States and France; the final indignity was suffered when his erstwhile political arch-enemy, the English polemicist William Cobbett, dug up Paine’s earthly remains and had them shipped to England, where they were later lost. But, as Seth Cotlar and others have shown, Paine’s influence did not end with his death; nor was it limited to the arguments for independence he outlined in Common Sense. Rather, it was the groundbreaking Rights of Man (1791–92) that became a touchstone for democratically-inclined radicals throughout the English-speaking world, leading one English admirer to conclude that “natural” rights (which for Paine included a right to education and basic economic security as well as rights of life, liberty, and property) applied to “the whole human race black or white, high or low, rich or poor.”[2] As Cotlar shows, the Rights of Man prompted even relatively mainstream figures like Robert Coram and Joel Barlow to adopt more democratic ideas of republican government, along with the notion of a “social debt” owed by those who benefitted from inequalities of property and status. Paine’s Age of Reason (1794) inspired secular humanists and “free thought” radicals (while also prompting a backlash from those offended by its frank rejection of Christian dogma), and his Agrarian Justice (1797) influenced several generations of radical land reformers on both sides of the Atlantic, from Paine’s English contemporary Thomas Spence to the English transplant George Henry Evans of the New York-based National Reform Association in the 1840s and ’50s.

Perhaps no other city in the United States was more receptive than New York to what has been termed Paine’s “cosmopolitan internationalism,” the idea embodied by the Rights of Man’s proclamation that “my country is the world, and my religion is to do good.” In 1793, members of the New York General Society of Mechanics and Tradesmen first toasted Paine as a fellow “mechanic,” and beginning in 1825, workingmen revived Paine’s memory with annual celebrations of his birthday, a tradition that lasted well into the following decade.[3] But perhaps Paine’s greatest legacy in New York lay not with the city’s “artisan republicans,” the workingmen who continued to host annual celebrations of his birthday into the 1830s, but with the transatlantic exiles from Britain, Ireland, and elsewhere, that made New York City their home after being persecuted by British authorities in the aftermath of the 1789 Revolution in France and throughout the period of the Napoleonic Wars. Members of the London Corresponding Society (LCS), perhaps the most working-class oriented of the various associations established in Britain to circulate radical and republican ideas, included Thomas Yarrow, who ended up in the New York area. Even before the physical arrival of such expatriate radicals in the United States, sailors and mariners had brought revolutionary news and radical tracts from Europe, and newspapers like Thomas Greenleaf’s New-York Journal carried notices about the LCS, the United Irishmen, and London’s Revolution Society, along with excerpts from Paine’s later works.[4]

The involvement of such radical expatriates in the city’s Democratic-Republican clubs (and later, the Jeffersonian Republicans) lent credence to Federalist charges that Republicans benefitted from an international constituency of “Jacobins,” and to William Cobbett’s depiction of the Jeffersonians as a motley collection of “butchers, tinkers, broken hucksters, and trans-Atlantic traitors.” Federalists, for their part, were charged by the democratically-inclined with being at the forefront of a “new aristocracy” of bankers, merchants, manufacturers, and monied men — a charge made plausible by the Federalists’ undisguised elitism as well as by their support for a system of banking and finance that disproportionally benefitted the well-off and well-connected, and their draconian approach to combatting subversion under the Alien and Sedition Acts. [5]

Through the 1790s, however, most skilled artisans in New York City remained strongly Federalist, a sign of their support for tariffs and pro-manufacturing policies. This began to change in the early 19th century with the spread of wage relationships, the decline of apprenticeship, indentured servitude, and other traditionally “paternalistic” forms of labor, and the division of labor in many trades, which undermined craft knowledge and made it increasingly difficult for journeymen to acquire a competency and set up shop for themselves. The first two decades of the 19th century were a notable period of labor strife in New York, with strikes by cordwainers (1808 and 1811), carpenters (1810), and masons (1819), among other groups. Striking workers throughout the period were often tried for “conspiracy,” and trade unions decried as “illegal combinations.” Meanwhile, wealth in the city became increasingly concentrated, with four percent of New Yorkers owning half of all non-corporate wealth by 1820.[6]

By the end of that decade, workers in New York, Philadelphia, Boston and more than a dozen smaller cities would form short-lived “Working Men’s” political parties, heralding the arrival of a new political consciousness among urban artisans and journeymen that would remain a potent force through the antebellum period and beyond. But in the decade after the end of the War of 1812, many urban workingmen — perhaps still reeling from the crushing blow to their livelihoods dealt by Jefferson’s Embargo, and despairing of political solutions as Republicans began to gravitate towards the business-friendly National Republican wing of the party — again cast their eyes further afield. In doing so, they looked simultaneously East, towards the new and radical ideas emanating from post-Waterloo Britain; and West, towards the sparsely-settled hinterlands and agriculturally rich wilderness of the Old Northwest.

It is difficult to pinpoint when the set of ideas known as socialism first made their way to the United States. But in England, radicals inspired by the sans-culottes of the French Revolution, among them John Thelwall and Thomas Hardy of the London Society, had begun to articulate penetrating critiques of the origins and legitimacy of certain kinds of property rights and the existence of inequalities of property and wealth. In the first two decades of the 19th century, British economic thinkers like John Gray, Thomas Hodgskin, William Thompson, and William Godwin extended this critique of the relationship between capital and labor and began to promulgate solutions, often focused on loosening the grip of Britain’s entrenched landed aristocracy. Some of these works found favor with self-taught workingman and amateur political economists in the United States, who had long imbibed Ricardian and Smithian notions of the labor theory of property (which held that legitimate property was the fruit of one’s labor). Thanks to a smattering of radical printers and bookshops and organs like William Duane’s Aurora and Greenleaf’s Journal, they had also likely been prepared by republican and utopian critiques of property like Harrington’s The Commonwealth of Oceana, Volney’s The Ruins, and Paine’s Rights of Man and Agrarian Justice. Indeed, the term “agrarianism” was widely used in the early United States as a synonym for socialism, a nod to both the agrarian law of the Roman Gracchi from whom Paine took inspiration and the early socialists’ emphasis on landed property.

By far the most influential proto-socialist in the early United States was Robert Owen, the Welsh-born manufacturer and reformer whose “factory village” in New Lanark, Scotland, was widely admired as a model for combining industry with the paternalistic but humane treatment of workers. Beginning in 1813, Owen began to translate his experiments at New Lanark into a holistic vision for a “New Moral World,” based on an understanding of human behavior as shaped by environment, rather than innate sinfulness or “character,” and calling for the reorganization of society into self-contained communities, where labor would be performed cooperatively rather than marked by destructive competition.[7]

Although as yet largely unknown to one another, American reformers were developing similar ideas across the Atlantic. In 1817, the Irish-born Philadelphian poet and reformer Thomas Branagan published The Pleasures of Contemplation, which praised Owen’s “benevolence” and appended an essay by Cornelius Blatchly, entitled Some Causes of Popular Poverty. Blatchly, a Quaker and graduate of the New York College of Physicians and Surgeons, blamed high interest rates and rents for the prevalence of high rates of poverty in New York. Like Paine in Agrarian Justice, Blatchly traced these factors to an illegitimate usurpation of property stemming from time immemorial; and like him, he called for the abolition or modification of inheritance laws to stem this injustice. While writing his next volume, Blatchly first encountered the works of Robert Owen, in which he recognized a kindred spirit of reform. The resulting Essay on Common Wealths incorporated the ideas of Owen and Joel Barlow along with favorable allusions to the religious communities then being formed by such groups as the Shakers, Moravians, and Mennonites, and Blatchly’s own Quaker-derived vision for “pure and perfect communities” comprised of mechanics and farmers. In 1820, Blatchly helped to organize the New York Society for Promoting Communities; and the Essay on Common Wealths was published in pamphlet form as an exposition of the Society’s ideas.[8]

On October 2, 1824, Robert Owen set sail from Liverpool for what would be his first voyage to the United States. He had been drawn by an uncertain but apparently irresistible prospect: the opportunity to purchase a tract of land on the distant Indiana frontier from the Harmony Society, a German-speaking religious community under the leadership of George Rapp. Among the first to greet Owen upon his disembarkation in New York on November 4 was Cornelius Blatchly and the group of artisans and professional men who comprised his Society for Promoting Communities. Over the next few years, they and other radicals and reformers in the New York region and beyond would form dozens of experimental cooperative communities — none more famous than Owen’s ill-fated experiment at New Harmony, Indiana.

Sean Griffin is an editor at Gotham. His forthcoming book, The Root and the Branch: Working-Class Reform and Antislavery, 1790-1860, reexamines the relationship between urban labor and abolition.

[1] Eric Foner, Foner, Tom Paine and Revolutionary America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1976).

[2] Thomas Hardy to unnamed British Corresponding Society, 18 April 1792, quoted in Seth Cotlar, Tom Paine’s America: The Rise and Fall of Transatlantic Radicalism in the Early Republic (Charlottesville and London: University of Virginia Press, 2011), 57.

[3] Foner, Tom Paine and Revolutionary America, 255, 264.

[4] Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker, The Many-Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners, and the Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic (Boston: Beacon Press, 2000); Cotlar, 73–74, 80, 165–67.

[5] Cobbett quoted in Sean Wilentz, Chants Democratic: New York City and the Rise of the American Working Class, 1788–1850 (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1984), 68.

[6] Wilentz, Chants Democratic, 26, 56–60.

[7] Owen’s A New View of Society: Or, Essays on the Formation of Human Character was first published in 1813, and subsequently under several different titles.

[8] Arthur Bestor, Backwoods Utopias: The Sectarian Origins and Owenite Phase of Communitarian Socialism in America: 1663–1829 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1950), 96–104.